Poaceae

| Poaceae (true grasses) Fossil range: Late Cretaceous[1] - present |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Flowering head of Meadow Foxtail (Alopecurus pratensis), with stamens exserted at anthesis

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Subfamilies | ||||||||||||

|

There are 7 subfamilies: |

Poaceae or Gramineae is a family in the Class Liliopsida of the flowering plants. Plants of this family are usually called grasses. There are about 600 genera and between 9,000–10,000 species of grasses (Kew Index of World Grass Species). Plant communities dominated by Poaceae are called grasslands; it is estimated that grasslands comprise 20% of the vegetation cover of the earth. This family is the most important of all plant families to human economies: it includes the staple food grains grown around the world, lawn and forage grasses, and bamboo, widely used for construction throughout east Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

The term "grass" is also applied to many grass-like plants not in the Poaceae, leading to plants of the Poaceae often being called "true grasses".

Contents |

Structure and growth

Grasses generally have the following characteristics (it is advisable to have a look at the image gallery for reference):

- General aspects

Poaceae have hollow stems called culms, plugged at intervals called nodes. Leaves are alternate, distichous (in one plane) or rarely spiral, parallel-veined and arise at the nodes. Each leaf is differentiated into a lower sheath hugging the stem for a distance and a blade with margin usually entire. The leaf blades of many grasses are hardened with silica phytoliths, which helps discourage grazing animals. In some grasses (such as sword grass) this makes the grass blades sharp enough to cut human skin. A membranous appendage or fringe of hairs, called the ligule, lies at the junction between sheath and blade, preventing water or insects from penetrating into the sheath.

Grass blades grow at the base of the blade and not from growing tips. This low growth point evolved in response to grazing animals and allows grasses to be grazed or mowed regularly without severe damage to the plant.[2]

- Reproduction

Flowers of Poaceae are peculiar. They are characteristically arranged in spikelets, each spikelet having one or more florets (the spikelets are further grouped into panicles or spikes). A spikelet consists of two (or sometimes fewer) bracts at the base, called glumes, followed by one or more florets. A floret consists of the flower surrounded by two bracts called the lemma (the external one) and the palea (the internal). The flowers are usually hermaphroditic (maize, monoecious, is an exception) and pollination is always anemophilous. The perianth is reduced to two scales, called lodicules, that expand and contract to spread the lemma and palea; these are generally interpreted to be modified sepals. This complex structure can be seen in the image on the left, portraying a wheat (Triticum aestivum) spike.

The fruit of Poaceae is a caryopsis.

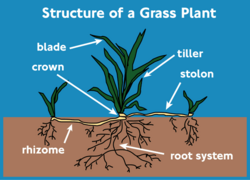

Grass plants also spread out from a parent plant. Growth habit describes the type of shoot growth present in particular grass plants and is directly related to their ability to spread out from the parent plant and ultimately form a clonal colony. There are three general classifications of growth habit present in grasses; bunch-type, stoloniferous, and rhizomatous.

Cool and Warm Season Grasses

The success of the grasses lies in part in their morphology and growth processes, and in part in their physiological diversity. The grasses divide into two physiological groups, using the C3 and C4 photosynthetic pathways for carbon fixation. The C4 grasses have a photosynthetic pathway linked to specialized Kranz leaf anatomy that particularly adapts them to hot climates and an atmosphere low in carbon dioxide.

C3 grasses are referred to as "cool season grasses" while C4 plants are considered "warm season grasses". Cool and warm season grasses can be annual or perennial.

- Annual Cool Season - wheat, rye, Annual Bluegrass, and oats

- Perennial Cool Season - orchardgrass, fescue, Kentucky Bluegrass and perennial ryegrass

- Annual Warm Season - corn, sudangrass, and pearlmillet

- Perennial Warm Season - big bluestem, indiangrass, bermudagrass, switchgrass, and old world bluestems.

Source for annual and perennial cool and warm season grass names (above) = http://forages.oregonstate.edu/projects/regrowth/main.cfm?PageID=33

Grass evolution

Until recently grasses were thought to have evolved around 55 million years ago, based on fossil records. However, recent findings of 65-million-year-old phytoliths resembling grass phytoliths (including ancestors of rice and bamboo) in Cretaceous dinosaur coprolites[1][3], may place the diversification of grasses to an earlier date.

The flowers of grass are reduced from the general monocotyledon type. The immediate ancestor of the first grass may have been a small Liliaceous plant with rhizomes and many small flowers, growing in dense patches, which adopted wind pollination to escape limitations caused by shortage of insects to pollinate the flowers.

Subfamilies and genera

- See also: List of Poaceae genera

The grass family has been divided into seven subfamilies:

- Arundinoideae, including giant reed, common reed

- Bambusoideae, including bamboo, rice

- Centothecoideae, a small subfamily of 11 genera

- Chloridoideae, including the windmill grasses

- Panicoideae, including panic grass, maize, sorghum, sugar cane, most millets, bluestem grasses

- Pooideae, including wheat, barley, oats

- Stipoideae, including feather grass

Economic importance

Grasses are, in human terms, perhaps the most economically important plant family. Grasses' economic importance stems from several areas, including food production, industry, and lawns.

Food production

Agricultural grasses grown for their edible seeds are called cereals. Three cereals– rice, wheat, and maize (corn)– provide more than half of all calories eaten by humans.[4] Of all crops, 70% are grasses.[5] Cereals constitute the major source of carbohydrate for humans and perhaps the major source of protein, and include rice in southern and eastern Asia, maize in Central and South America, and wheat and barley in Europe, northern Asia and the Americas.

Sugarcane is the major source of sugar production. Many other grasses are grown for forage and fodder for animal food, particularly for sheep and cattle. Some other grasses are of major importance for foliage production, thereby indirectly providing more human calories.

Industry

Grasses are used for construction. Scaffolding made from bamboo is able to withstand typhoon force winds that would break steel scaffolding.[6] Larger bamboos and Arundo donax have stout culms that can be used in a manner similar to timber, and grass roots stabilize the sod of sod houses. Arundo is used to make reeds for woodwind instruments, and bamboo is used for innumerable implements.

Grass fibre can be used for making paper, and for biofuel production.

Phragmites australis (common reed) is important in water treatment, wetland habitat preservation and land reclamation in the Old World.

Lawns

Grasses are the primary plant used in lawns, which themselves derive from grazed grasslands in Europe.

Although supplanted by artificial turf in some games, grasses are still an important covering of playing surfaces in many sports, including football, tennis, golf, cricket, and softball/baseball.

Economically important grasses

|

|

|

Ecological importance

With 10,025 known species, the Poaceae is the fourth largest plant family. Only Orchidaceae, Asteraceae, and Fabaceae have more species, although with over 10,000 species the Rubiaceae is not far behind.[7]

Biomes dominated by grasses are called grasslands. If only large contiguous chunks of grasslands are counted, these biomes cover 31% of the planet's land.[6] Grasslands go by various names depending on location, including pampas, plains, steppes, or prairie.

Grasses are used as food plants by many species of butterflies and moths; see List of Lepidoptera that feed on grasses.

The evolution of large grazing animals in the Cenozoic has contributed to the spread or grasses. Without large grazers, a clearcut of fire-destroyed area would soon be colonized by grasses and, if there is enough rain, tree seedlings. The tree seedlings would eventually produce shade, which kills most grasses. Large animals, however, trample the seedlings, killing the trees. Grasses persist because their lack of woody stems helps them to resist the damage of trampling.[8]

Grass and society

Grass has long had significance in human society. It has been cultivated as a food source for domesticated animals for up to 10,000 years, and has been used to make paper since at least as early as 2400 B.C.

Some common aphorisms involve grass. For example:

- "The grass is always greener on the other side" suggests that an alternate state of affairs will always seem preferable to one's own.

- "Don't let the grass grow under your feet" tells someone to get moving.

- "A snake in the grass" means dangers that are hidden.

- "When elephants fight, it is the grass who suffers" tells of bystanders caught in the crossfire.

Image gallery

See also

- agrostology

- grass

- sedges

Further reading

- Chapman, G.P. and W.E. Peat. 1992. An Introduction to the Grasses. CAB International, Wallingford.

- Cheplick, G.P. 1998. Population Biology of Grasses. Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Piperno, D. R.; Sues, H.D. (2005). "Dinosaurs Dined on Grass". Science 310 (5751): 1126hor = Piperno, D.R.. doi:. PMID 16293745.

- ↑ David Attenborough (1984). The Living Planet. British Broadcasting Corporation. pp. 113–4. ISBN 0-563-20207-6.

- ↑ Prasad, V.; Stroemberg, C.A.E.; Alimohammadian, H.; Sahni, A. (2005). "Dinosaur Coprolites and the Early Evolution of Grasses and Grazers". Science(Washington) 310 (5751): 1177–1180. doi:. PMID 16293759.

- ↑ Peter H. Raven & George B. Johnson (1995). Carol J. Mills (ed). ed.. Understanding Biology (3rd ed.). WM C. Brown. pp. 536. ISBN 0-697-22213-6.

- ↑ George Constable (ed), ed. (1985). Grasslands and Tundra. Planet Earth. Time Life Books. pp. 19. ISBN 0-8094-4520-4.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 George Constable (ed), ed. (1985). Grasslands and Tundra. Planet Earth. Time Life Books. pp. 20. ISBN 0-8094-4520-4.

- ↑ "Angiosperm phylogeny website". Retrieved on 2007-10-07.

- ↑ David Attenborough (1984). The Living Planet. British Broadcasting Corporation. pp. 137.

External links

- TurfFiles by North Carolina State University

- Kew Index of World Grass Species

- Definitions of Grass structures

- The grass genera of the world, L. Watson and M. J. Dallwitz (1992 onwards)

- The families of flowering plants.

- The grass genera of the world

- Content summary.

- Interactive Keys to North American Grasses at Utah State University

- Family Gramineae Flowers in Israel