Glagolitic alphabet

| Glagolitic | |

| Type | Alphabet |

|---|---|

| Spoken languages | Old Church Slavic |

| Created by | Saints Cyril and Methodius |

| Time period | 862/863 to the Middle Ages |

| ISO 15924 | Glag |

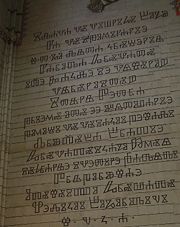

A page from the Zograf Kodex with text of the Gospel of Luke |

|

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | |

The Glagolitic alphabet (pronounced /ɡlæɡəˈlɪtɪk/), also known as Glagolitsa, is the oldest known Slavic alphabet. The name was not coined until many centuries after its creation, and comes from the Old Slavic glagolъ "utterance" (also the origin of the Slavic name for the letter G). Since glagolati also means to speak, the glagolitsa poetically referred to "the marks that speak".

The name Glagolitic is translated in Belarusian глаголіца' (hlaholitsa), Bulgarian and Macedonian as глаголица (transliterated glagolica), Croatian glagoljica, Czech hlaholice, Polish głagolica, Russian глаголица (glagólitsa), Serbian глагољица/glagoljica, Slovenian glagolica, Slovak hlaholika, Ukrainian глаголиця (hlaholytsia).

Contents |

Origins of the Glagolitic characters

The number of letters in the original Glagolitic alphabet is not known, but may have been close to its Greek model. The 41 letters we know today include letters for non-Greek sounds which may have been added by Saint Cyril, as well as ligatures added in the 12th century under the influence of Cyrillic, as Glagolitic lost its dominance.[1] In later centuries the number of letters drops dramatically, to less than 30 in modern Croatian and Czech recensions of the Church Slavic language. Twenty-four of the 41 original Glagolitic letters (see table below) probably derive from graphemes of the medieval cursive Greek small alphabet, but have been given an ornamental design.

The source of the other consonantal letters is unknown. If they were added by Cyril, it is likely that they were taken from an alphabet used for Christian scripture. It is frequently proposed that the letters sha Ⱎ, tsi Ⱌ, and cherv Ⱍ were taken from the the letters shin ש and tsadi צ of the Hebrew alphabet, and that Ⰶ zhivete derives from Coptic janja Ϫ. However, Cubberley (1996) suggests that if a single prototype were presumed, that the most likely source would be Armenian. Other proposals include the Samaritan alphabet, which Cyril got to know during his journey to the Khazars in Cherson.

| South Slavic languages and dialects |

| Western South Slavic |

| Croatian Western Štokavian Čakavian · Kajkavian Burgenland · Molise |

| Serbian Eastern Štokavian Slavoserbian Romano-Serbian · Užice |

| Bosnian Central Štokavian |

| Slovene dialects |

| Differences between standard Croatian / Serbian / Bosnian |

|

Deprecated or non-ISO

Serbo-Croatian · Bunjevacrecognized languages Montenegrin · Šokac |

| Eastern South Slavic |

| Church Slavonic (Old) |

| Bulgarian Banat · Greek Slavic Shopski · Meshterski · more |

| Macedonian Dialects Aegean Macedonian Spoken Macedonian Standard Macedonian |

| Transitional dialects |

| Eastern-Central Torlak dialects · Našinski |

| Western-Central Kajkavian |

| Alphabets |

| Modern Gaj's Latin1 · Serbian Cyrillic Macedonian Cyrillic Bulgarian Cyrillic Slovene |

| Historical Bohoričica · Dajnčica · Metelčica Arebica · Bosnian Cyrillic Glagolitic · Early Cyrillic |

| 1 Includes Banat Bulgarian alphabet. |

Glagolitic letters were also used as numbers, similarly to Cyrillic numerals. Unlike Cyrillic numerals, which inherited their numeric value from the corresponding Greek letter (see Greek numerals), Glagolitic letters were assigned values based on their native alphabetic order.

History

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Although popularly attributed to Saints Cyril and Methodius and the introduction of Christianity, the origin of the Glagolitic alphabet is obscure. It may have developed from cursive Greek in what is now the Republic of Macedonia centuries earlier, only to be formalized and expanded with new letters for non-Greek sounds by Saint Cyril.[1]

Rastislav, the Knyaz (Duke) of Great Moravia, wanted to weaken the dependence of his Slavic empire on East Frankish priests, so in 862 he had the Byzantine emperor send two missionaries, Saints Cyril and Methodius, to Great Moravia. Cyril formalized and augmented Glagolitic to more perfectly record the Slavic language. The alphabet was used between 863 and 885 for government and religious documents and books, and at the Great Moravian Academy (Veľkomoravské učilište) founded by Cyril, where followers of Cyril and Methodius were educated (also by Methodius himself).

In 886, an East Frankish bishop of Nitra named Wiching banned the script and jailed 200 followers of Methodius (mostly students of the original academy). They were then dispersed or, according to some sources, sold as slaves by Franks. Many of them (including Naum, Clement, Angelarious, Sava and Gorazd), however, reached Bulgaria and were commissioned by Boris I of Bulgaria to teach and instruct the future clergy of the state into the Slavic languages. After the adoption of Christianity in Bulgaria in 865, religious ceremonies and Divine Liturgy were conducted in Greek by clergy sent from the Byzantine Empire, using the Byzantine rite. Fearing growing Byzantine influence and weakening of the state, Boris viewed the introduction of the Slavic alphabet and language in church use as a way to preserve the independence of Slavic Bulgaria from Greek Constantinople. As a result of Boris's measures, two academies in Ohrid and Preslav were founded.

From there, the students traveled to various other places and spread the use of their alphabet. Some went to Croatia (into Dalmatia), where the squared variant arose and where the Glagolitic remained in use for a long time. In 1248, Pope Innocent IV gave the Croats of southern Dalmatia the unique privilege of using their own language and this script in the Roman Rite liturgy. Formally given to bishop Philip of Senj, the permission to use the Glagolitic liturgy (the Roman Rite conducted in Slavic language instead of Latin, not the Byzantine rite), actually extended to all Croatian lands, mostly along the Adriatic coast. The Holy See had several Glagolitic missals published in Rome. Authorisation for use of this language was extended to some other Slavic regions between 1886 and 1935.[2] In missals, the Glagolitic script was eventually replaced with the Latin alphabet, but the use of the Slavic language in the Mass continued, until replaced by the modern vernacular languages.

Some of the students of the Ohrid academy went to Bohemia where the alphabet was used in the 10th and 11th century, along with other scripts. Glagolitic was also used in Kievan Rus.

In Croatia, from the 12th century onwards, Glagolitic inscriptions appeared mostly in littoral areas: Istra, Primorje, Kvarner and Kvarner islands, notably Krk, Cres and Lošinj; in Dalmatia, on the islands of Zadar, but there were also findings in inner Lika and Krbava, reaching to Kupa river, and even as far as Međimurje and Slovenia.

Until 1992, it was believed that Glagolitsa in Croatia was present only in those areas, and then, in 1992, the discovery of Glagolitic inscriptions in churches along the Orljava river in Slavonia, totally changed the picture (churches in Brodski Drenovac, Lovčić and some others), showing that use of Glagolitic alphabet was spread from Slavonia also.[3]

At the end of the 9th century, one of these students of Methodius who was settled in Preslav (Bulgaria) created the Cyrillic alphabet, which almost entirely replaced the Glagolitic during the Middle Ages. The Cyrillic alphabet is derived from the Greek alphabet, with (at least 10) letters peculiar to Slavic languages being derived from the Glagolitic.

Nowadays, Glagolitic is only used for Church Slavic (Croatian and Czech recensions).

Versions of authorship and name

The tradition that the alphabet was designed by Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius has not been universally accepted. A less common belief, contradicting allochtonic Slovene origin, was that the Glagolitic was created or used in the 4th century by St. Jerome, hence the alphabet is sometimes named Hieronymian.

It is also acrophonically called azbuki from the names of its first two letters, on the same model as 'alpha' + 'beta'. (Actually, the word means simply "alphabet", see its a bit later form azbuka for the Cyrillic alphabet). The Slavs of Great Moravia (present-day Slovakia and Moravia), Hungary, Slovenia and Slavonia were called Slověne at that time, which gives rise to the name Slovenish for the alphabet. Some other, more rare, names for this alphabet are Bukvitsa (from common Slavic word 'bukva' meaning 'letter', and a suffix '-itsa') and Illyrian.

Hieronymian version

In the Middle Ages, Glagolitsa was also known as "St. Jerome's script" due to popular mediaeval legend (created by Croatian scribes in 13th century) ascribing its invention to St Jerome (342-429).

Till end of the 18th century, a strange but widespread opinion dominated that the glagolitic writing system, which was in use in Dalmatia and Istria along with neighboring islands, including the translation of the Holy Scripture, owe their existing to the famous church father St. Jerome. Knowing him as the author of the Latin Vulgate, considering him - as Dalmatian-born - a Slav, and especially a Croatian, the home-bred slavic intellectuals in Dalmatia very early began to ascribe to him the invention of glagolitsa, possibly on purpose, with the intention of more successfully defending both Slavic writing and the Slavic holy service against prosecutions and prohibitions from Rome's hierarchy, thus using the honourable opinion of the famous Latin holy father to protect their church rituals which were inherited from the Greeks Cyril and Methodius. We don't know who was the first to put in motion this unscientifically based tradition about St. Jerome's authorship of the glagolitic script and translation of the Holy Scripture, but in 1248 this version came to the knowledge of Pope Innocent IV. <…> The belief in St. Jerome as an inventor of the glagolitic lasted many centuries, not only at his homeland, i.e. in Dalmatia and Croatia, not only in Rome, due to Slavs living there… but also in the West. In the 14th century, Croatian monks brought the legend to the Czechs, and even the Emperor Charles IV believed them[4]

The epoque of traditional attribution of the script to Jerome ended probably in 1812.[5] In modern times, only certain marginal authors share this point of view, usually "re-discovering" one of already known mediaeval sources.[6]

Naïve etymology versions of the word "glagolitsa"

- glago+litsa: "glago" is (an impossible) shortcut from "glagolъ", "litsa" means "faces" (plural from Old Slavic "lice" (litse, face), Russian "лицо" (litso, face), Bulgarian "лице" (litse, face) etc.); thus glagolitsa = talking faces

- glago+li+tsa, where particle 'li' means 'if' or '?', and 'co' (pronounced "tso") - 'what' in Polish and Czech; result has to mean 'what if' or 'what about' (those faces) talking?

Pre-Glagolitic Slavic writing systems

A hypothetical pre-Glagolitic writing system is typically referred to as cherty i rezy (strokes and incisions)[7] - but no material evidence of the existence of any pre-Glagolitic Slavic writing system has been found, except for a few brief and vague references in old chronicles and "lives of the saints". All artefacts presented as evidence of pre-glagolitic Slavic inscriptions have later been identified as texts in known scripts and in known non-Slavic languages, or as fakes.[8] The well-known Chernorizets Hrabar's strokes and incisions are usually considered to be a reference to a kind of property mark or alternatively fortune-telling signs. Some 'Russian letters' found in one version of St. Cyril's life are explainable as misspelled 'Syrian letters' (in Slavic, the roots are very similar: rus- vs. sur- or syr-), etc.

Characteristics

The alphabet has two variants: an early rounded form, used for Old Church Slovanic, and a late squared form, used for Croatian. See an image of both variants (incomplete). Or for more details The values of many of the letters are thought to have been displaced under Cyrillic influence, or to have become confused through the early spread to different dialects, so that the original values are not always clear. For instance, the letter yu Ⱓ is thought to have perhaps originally had the value /u/, but was displaced by the adoption of an ow ligature Ⱆ under the influence of later Cyrillic. Other letters were late creations after a Cyrillic model.

The following table lists each letter in its modern order, giving a picture (round variant), its name, its approximate sound in the IPA, suggestions for its origin, and the corresponding modern Cyrillic letter. Several letters, such as the nasal vowels (yus), have no modern counterpart.

| Letter | Old Church Slavic name | Church Slavic name | Meaning of name | Sound | Suggested origins | Cyrillic equivalent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ⰰ | Az' | Az | I | /ɑ/ | Greek alpha α; the sign of the cross. | (А а) A | |

| Ⰱ | Buky | Buky | /b/ | Unknown | (Б б) Be | ||

| Ⰲ | Vede | Vedi | Look/See | /ʋ/ | Greek beta β | (В в) Ve | |

| Ⰳ | Glagolji | Glagoli | Verb | /ɡ/ | Greek gamma γ | (Г г) Ge | |

| Ⰴ | Dobro | Dobro | Kindness/Good | /d/ | Greek delta δ | (Д д) De | |

| Ⰵ | Jest' | Jest | Is/Exists | /ɛ/ | Greek epsilon ε or sampi ϡ | (Е е) Ye; (Э э) E | |

| Ⰶ | Zhivete | Zhivete | Life/Live | /ʒ/ | Coptic janja ϫ | (Ж ж) Zhe | |

| Ⰷ | Dzelo | Dzelo | Green | /ʣ/ | Greek zeta ζ; final sigma ς | (Ѕ ѕ) Macedonian Dze | |

| Ⰸ | Zemlja | Zemlja | Earth | /z/ | Greek theta θ | (З з) Ze | |

| Ⰺ, Ⰹ | Izhe | Izhe | /i/, /j/ | Greek iota with dieresis ϊ | (И и) I; also (Й й) Short I | ||

| Ⰻ | I | I | /i/, /j/ | Unknown; Christian symbols circle and triangle | (І і) Ukrainian I; (Ї, ї) Ukrainian Yi | ||

| Ⰼ | [Djerv'] | /ʥ/ | Unknown | (Ћ ћ) Serbian Tshe; later (Ђ ђ) Serbian Dje | |||

| Ⰽ | Kako | Kako | How | /k/ | Unknown; Greek kappa κ | (К к) Ka | |

| Ⰾ | Ljudije | Ljudi | People | /l/, /ʎ/ | Greek lambda λ | (Л л) El | |

| Ⰿ | Mislete | Mislete | Thought/Think | /m/ | Greek mu μ | (М м) Em | |

| Ⱀ | Nash' | Nash | Ours | /n/, /ɲ/ | Unknown | (Н н) En | |

| Ⱁ | On' | On | He | /ɔ/ | Unknown | (О о) O | |

| Ⱂ | Pokoji | Pokoj | Calmness | /p/ | Greek pi π | (П п) Pe | |

| Ⱃ | Rtsi | Rtsi | /r/ | Greek rho ρ | (Р р) Er | ||

| Ⱄ | Slovo | Slovo | Word/Letter | /s/ | Unknown; Christian symbols circle and triangle | (С с) Es | |

| Ⱅ | Tvrdo | Tverdo | Solid/Hard | /t/ | Greek tau τ | (Т т) Te | |

| Ⱆ | Uk' | Uk | /u/ | Ligature of on and izhitsa, after the Cyrillic model | (У у) U | ||

| Ⱇ | Frt' | Fert | /f/ | Greek phi φ | (Ф ф) Ef | ||

| Ⱈ | Kher' | Kher | /x/ | Unknown; glagoli | (Х х) Ha | ||

| Ⱉ | Oht' | Oht, Omega | /ɔ/ | Greek omega ω | (Ѿ ѿ) Ot | ||

| Ⱋ | Shta | Shta | What | /tʲ/, /ʃt/ | Unknown; later interpreted as a ligature of sha on top cherv or tverdo | (Щ щ) Shcha | |

| Ⱌ | Tsi | Tsi | /ʦ/ | Hebrew tsade, final form (ץ) | (Ц ц) Tse | ||

| Ⱍ | Chrv' | Cherv | Worm | /ʧ/ | Hebrew tsade, non-final form (צ) | (Ч ч) Che | |

| Ⱎ | Sha | Sha | /ʃ/ | Hebrew shin (ש) | (Ш ш) Sha | ||

| Ⱏ | Yer' | Yer | /ɯ/ | Modification of on | (Ъ ъ) hard sign | ||

| ⰟⰊ | Yery | Yery | /ɨ/ | Ligature, see the note under the table | (Ы ы) Yery | ||

| Ⱐ | Yerj' | Yerj | /ɘ/ | Modification of on | (Ь ь) soft sign | ||

| Ⱑ | Yat' | Yat | /æ/, /jɑ/ | Epigraphic Greek alpha Α; ligature of Greek E+I | (Ѣ ѣ) Yat | ||

| Ⱖ | (not a real letter) | */jo/ | (a hypothetical component of yons below; /jo/ was not possible at the time) | (Ё ё) O iotified | |||

| Ⱓ | Yu | Yu | /ju/ | Greek upsilon υ | (Ю ю) Yu | ||

| Ⱔ | [Ens'] | Ya, Small yus | /ɛ̃/ | Greek epsilon ε | (Ѧ ѧ) Small yus, later (Я я) Ya | ||

| Ⱗ | [Yens'] | [Small iotated yus] | /jɛ̃/ | Ligature of yest plus ens for nasality; after the Cyrillic model | (Ѩ ѩ) Small iotated yus | ||

| Ⱘ | [Ons'] | [Big yus] | /ɔ̃/ | Ligature of on plus ens for nasality | (Ѫ ѫ) Big yus | ||

| Ⱙ | [Yons'] | [Big iotated yus] | /jɔ̃/ | Unknown ligature, after the Cyrillic model | (Ѭ ѭ) Big iotated yus | ||

| Ⱚ | [Thita] | Fita | /θ/ | Greek theta θ | (Ѳ ѳ) Fita | ||

| Ⱛ | Izhitsa | Izhitsa | /ʏ/, /i/ | Ligature of izhe and yer | (Ѵ ѵ) Izhitsa | ||

Note that Yery is simply a digraph of Yer and I. In older texts, Uk and three out of four Yuses also can be written as digraphs, in two separate parts. The order of Izhe and I varies from source to source, as does the order of the various forms of Yus. Correspondence between Glagolitic Izhe and I - and Cyrillic И and I - is not known; textbooks and dictionaries often mention one of two possible versions and keep silence about the existence of the opposite one.

Unicode

The Glagolitic alphabet was added to Unicode in version 4.1. The codepoint range is U+2C00 – U+2C5E. See Mapping of Unicode Characters for context.

| Glagolitic Unicode.org chart (PDF) |

||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+2C0x | Ⰰ | Ⰱ | Ⰲ | Ⰳ | Ⰴ | Ⰵ | Ⰶ | Ⰷ | Ⰸ | Ⰹ | Ⰺ | Ⰻ | Ⰼ | Ⰽ | Ⰾ | Ⰿ |

| U+2C1x | Ⱀ | Ⱁ | Ⱂ | Ⱃ | Ⱄ | Ⱅ | Ⱆ | Ⱇ | Ⱈ | Ⱉ | Ⱊ | Ⱋ | Ⱌ | Ⱍ | Ⱎ | Ⱏ |

| U+2C2x | Ⱐ | Ⱑ | Ⱒ | Ⱓ | Ⱔ | Ⱕ | Ⱖ | Ⱗ | Ⱘ | Ⱙ | Ⱚ | Ⱛ | Ⱜ | Ⱝ | Ⱞ | |

| U+2C3x | ⰰ | ⰱ | ⰲ | ⰳ | ⰴ | ⰵ | ⰶ | ⰷ | ⰸ | ⰹ | ⰺ | ⰻ | ⰼ | ⰽ | ⰾ | ⰿ |

| U+2C4x | ⱀ | ⱁ | ⱂ | ⱃ | ⱄ | ⱅ | ⱆ | ⱇ | ⱈ | ⱉ | ⱊ | ⱋ | ⱌ | ⱍ | ⱎ | ⱏ |

| U+2C5x | ⱐ | ⱑ | ⱒ | ⱓ | ⱔ | ⱕ | ⱖ | ⱗ | ⱘ | ⱙ | ⱚ | ⱛ | ⱜ | ⱝ | ⱞ | |

Miscellanea

- In Istria, a road connecting the hill towns of Roč and Hum is known as the "Glagolitic Avenue." Along this road is a series of 1970s-era monuments to the Glagolitic alphabet. The town of Hum also contains many examples of Glagolitic script on various monuments in its walls.

- Perhaps the most well-known public display of Glagolitic script is found in the cathedral at Zagreb.

- Slovak passports issued prior to the EU accession had their pages watermarked by Glagolitic letters.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Paul Cubberley (1996) "The Slavic Alphabets". In Daniels and Bright, eds. The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.

- ↑ "The right to use the Glagolitic language at Mass with the Roman Rite has prevailed for many centuries in all the south-western Balkan countries, and has been sanctioned by long practice and by many popes" (Dalmatia in Catholic Encyclopedia); "In 1886 it arrived to the Principality of Montenegro, followed by the Kingdom of Serbia in 1914, and the Republic of Czechoslovakia in 1920, but only for feast days of the main patron saints. The 1935 concordat with the Kingdom of Yugoslavia anticipated the introduction of the Slavic liturgy for all Croatian regions and throughout the entire state" (The Croatian Glagolitic Heritage by Marko Japundzić).

- ↑ (Croatian) Glagoljaška baština u Slavonskom Kobašu, Slavonskobrodska televizija, News from February 25, 2007.

- ↑ До конца XVIII века господствовало странное, но широко распространенное мнение, что глаголическое письмо, бывшее в употреблении в Далмации и Истрии с прилегающими островами и в приморской Хорватии, вместе с переводом священного писания, обязано своим существованием знаменитому отцу церкви св. Иерониму. Зная о нем как авторе латинской «Вульгаты», считая его же как уроженца Далмации славянином, в частности хорватом, домашняя славянская интеллигенция Далмации стала очень рано присваивать ему изобретение глаголицы, быть может, нарочно, с тем умыслом, чтобы успешнее отстаивать и письмо, и богослужение славянское от преследований и запретов со стороны римской иерархии, прикрывая авторитетным именем знаменитого латинского отца церкви свой от греков Кирилла и Мефодия унаследованный обряд. Кем впервые пущено в ход это ни на чем не основанное ученое предание об авторстве св. Иеронима по части глаголического письма и перевода св. писания, мы не знаем, но в 1248 году оно дошло уже до сведения папы Иннокентия IV. <…> Много столетий продолжалась эта вера в Иеронима как изобретателя глаголического письма, не только дома, т. е. в Далмации и Хорватии, не только в Риме, через проживавших там славян… но также и на западе. В Чехию предание занесено в XIV столетии хорватскими монахами-глаголитами, которым поверил даже император Карл IV. (Jagić 1911, pp. 51-52)

- ↑ P. Solarić's "Букварь славенскiй трiазбучный" (Three-alphabet Slavic Primer), Venice, 1812 mentions the version as a fact of scinnce (see Jagić 1911, p. 52; Vajs 1932, p. 23).

- ↑ For example, K. Šegvić in Nastavni vjesnik, XXXIX, sv. 9-10, 1931, refers to a work of Rabanus Maurus. (see Vajs 1932, p. 23).

- ↑ Chernorizets Hrabar An Account of Letters; Preslav 895; Oldest manuscript 1348

- ↑ L. Niederle, "Slovanské starožitnosti" (Slavic antiquities), III 2, 735; citation can be found in Vajs 1932, p. 4.

Literature

- Branko Franolić, Mateo Zagar: A Historical Outline of Literary Croatian & The Glagolitic Heritage of Croatian Culture, Erasmus & CSYPN, London & Zagreb 2008 ISBN 978-953-6132-80-5

- Bauer, Antun: Armeno-kavkasko podrijetlo starohrvatske umjetnosti, glagoljice i glagoljaštva. Tko su i odakle Hrvati, p. 65-69, Znanstveno društvo za proučavanje etnogeneze, Zagreb 1992.

- Franolić, Branko: Croatian Glagolitic Printed Texts Recorded in the British Library General Catalogue. Zagreb - London - New York, Croatian Information Center, 1994. 49 p.

- Fučić, Branko: Glagoljski natpisi. (In: Djela Jugoslavenske Akademije Znanosti i Umjetnosti, knjiga 57.) Zagreb, 1982. 420 p.

- Fullerton, Sharon Golke: Paleographic Methods Used in Dating Cyrillic and Glagolitic Slavic Manuscripts. (In: Slavic Papers No. 1.) Ohio, 1975. 93 p.

- Гошев, Иван: Рилски глаголически листове. София, 1956. 130 p.

- Jachnow, Helmut: Eine neue Hypothese zur Provenienz der glagolitischen Schrift - Überlegungen zum 1100. Todesjahr des Methodios von Saloniki. In: R. Rathmayr (Hrsg.): Slavistische Linguistik 1985, München 1986, 69-93.

- Jagić, Vatroslav: Glagolitica. Würdigung neuentdeckter Fragmente, Wien, 1890.

- Ягичъ, И. В.: Глаголическое письмо. In: Энциклопедiя славянской филологiи, вып. 3, Спб., 1911.

- Japundžić, Marko: Postanak glagoljskog pisma. Tromjesečnik Hrvatska, srpanj 1994, p. 62-73.

- Japundžić, Marko: Tragom hrvatskog glagolizma. Zagreb 1995, 173 p.

- Japundžić, Marko: Hrvatska glagoljica. Hrvatska uzdanica, Zagreb 1998, 100 p.

- Japundžić, Marko: Gdje, kada i kako je nastala glagoljica i ćirilica. Staroiransko podrijetlo Hrvata p. 429-444, Naklada Z. Tomičić, Zagreb 1999.

- Kiparsky, Valentin: Tschernochvostoffs Theorie über den Ursprung des glagolitischen Alphabets In: M. Hellmann u.a. (Hrsg.): Cyrillo-Methodiana. Zur Frühgeschichte des Christentums bei den Slaven, Köln 1964, 393-400.

- Miklas, Heinz (Hrsg.): Glagolitica: zum Ursprung der slavischen Schriftkultur, Wien, 2000.

- Steller, Lea-Katharina: A glagolita írás In: B.Virághalmy, Lea: Paleográfiai kalandozások. Szentendre, 1995. ISBN 9634509223

- Vais, Joseph: Abecedarivm Palaeoslovenicvm in usum glagolitarum. Veglae [Krk], 1917. XXXVI, 74 p.

- Vajs, Josef: Rukovet hlaholske paleografie. Uvedení do knizního písma hlaholskeho. V Praze, 1932. 178 p, LIV. tab.

- Žubrinić, Darko: Biti pismen - biti svoj. Crtice iz povijesti glagoljice. Hrvatsko književno društvo Sv. Jeronima, Zagreb 1994, 297 p.

See also

- Glagolitic Mass

- Glagolitic Alphabet Day

External links

- Croatian Glagolitic Script

- Croatian Glagolitic Script

- The Glagolitic alphabet at omniglot.com

- The Budapest Glagolitic Fragments - links to a Unicode Glagolitic font, Dilyana

- Glagolitic Fonts

- Usage of numbers

|

|||||||||||