Gestational diabetes

| Gestational diabetes Classification and external resources |

|

| ICD-10 | O24. |

|---|---|

| ICD-9 | 648.8 |

| MedlinePlus | 000896 |

| MeSH | D016640 |

Gestational diabetes (or gestational diabetes mellitus, GDM) is a condition in which women without previously diagnosed diabetes exhibit high blood glucose levels during pregnancy.

Gestational diabetes generally has few symptoms and it is most commonly diagnosed by screening during pregnancy. Diagnostic tests detect inappropriately high levels of glucose in blood samples. Gestational diabetes affects 3-10% of pregnancies, depending on the population studied.[1] No specific cause has been identified, but it is believed that the hormones produced during pregnancy increase a woman's resistance to insulin, resulting in impaired glucose tolerance.

Babies born to mothers with gestational diabetes are at increased risk of problems typically such as being large for gestastional age (which may lead to delivery complications), low blood sugar, and jaundice. Gestational diabetes is a treatable condition and women who have adequate control of glucose levels can effectively decrease these risks.

Women with gestational diabetes are at increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus after pregnancy, while their offspring are prone to developing childhood obesity, with type 2 diabetes later in life. Most patients are treated only with diet modification and moderate exercise but some take anti-diabetic drugs, including insulin.

| Diabetes mellitus

|

|---|

| Types of Diabetes |

| Diabetes mellitus type 1 Diabetes mellitus type 2 Gestational diabetes Pre-diabetes: |

| Disease Management |

| Diabetes management: •Diabetic diet •Anti-diabetic drugs •Conventional insulinotherapy •Intensive insulinotherapy |

| Other Concerns |

| Cardiovascular disease

Diabetic comas: Diabetic myonecrosis Diabetes and pregnancy |

| Blood tests |

| Blood sugar Fructosamine Glucose tolerance test Glycosylated hemoglobin |

Contents |

Definition

Gestational diabetes is formally defined as "any degree of glucose intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy".[2] This definition acknowledges the possibility that patients may have previously undiagnosed diabetes mellitus, or may have developed diabetes coincidentally with pregnancy. Whether symptoms subside after pregnancy is also irrelevant to the diagnosis .[3]

Epidemiology

The frequency of gestational diabetes varies widely by study depending on the population studied and the study design. It occurs in between 5 and 10% of all pregnancies (between 1-14% in various studies).[3]

Pathophysiology

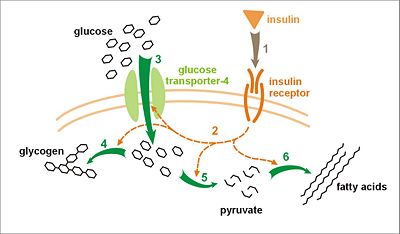

The precise mechanisms underlying gestational diabetes remain unknown. The hallmark of GDM is increased insulin resistance. Pregnancy hormones and other factors are thought to interfere with the action of insulin as it binds to the insulin receptor. The interference probably occurs at the level of the cell signaling pathway behind the insulin receptor.[4]. Since insulin promotes the entry of glucose into most cells, insulin resistance prevents glucose from entering the cells properly. As a result, glucose remains in the bloodstream, where glucose levels rise. More insulin is needed to overcome this resistance; about 1.5-2.5 times more insulin is produced in a normal pregnancy.[4]

Insulin resistance is a normal phenomenon emerging in the second trimester of pregnancy, which progresses thereafter to levels seen in non-pregnant patients with type 2 diabetes. It is thought to secure glucose supply to the growing fetus. Women with GDM have an insulin resistance they cannot compensate with increased production in the β-cells of the pancreas. Placental hormones, and to a lesser extent increased fat deposits during pregnancy, seem to mediate insulin resistance during pregnancy. Cortisol and progesterone are the main culprits, but human placental lactogen, prolactin and estradiol contribute too.[4]

It is unclear why some patients are unable to balance insulin needs and develop GDM, however a number of explanations have been given, similar to those in type 2 diabetes: autoimmunity, single gene mutations, obesity, and other mechanisms.[5]

Because glucose travels across the placenta (through diffusion facilitated by GLUT3 carriers), the fetus is exposed to higher glucose levels. This leads to increased fetal levels of insulin (insulin itself cannot cross the placenta). The growth-stimulating effects of insulin can lead to excessive growth and a large body (macrosomia). After birth, the high glucose environment disappears, leaving these newborns with ongoing high insulin production and susceptibility to low blood glucose levels (hypoglycemia).[6]

Risk factors and symptoms

Classical risk factors for developing gestational diabetes are the following:[7]

- a previous diagnosis of gestational diabetes or prediabetes, impaired glucose tolerance, or impaired fasting glycaemia

- a family history revealing a first degree relative with type 2 diabetes

- maternal age - a woman's risk factor increases as she gets older (especially for women over 35 years of age)

- ethnic background (those with higher risk factors include African-Americans, Afro-Caribbeans, Native Americans, Hispanics, Pacific Islanders, and people originating from the Indian subcontinent)

- being overweight, obese or severely obese increases the risk by a factor 2.1, 3.6 and 8.6, respectively.[8]

- a previous pregnancy which resulted in a child with a high birth weight (>90th centile, or >4000 g (8 lbs 12.8 oz))

- previous poor obstetric history

In addition to this, statistics show a double risk of GDM in smokers.[9] Polycystic ovarian syndrome is also a risk factor.[7] Some studies have looked at more controversial potential risk factors, such as short stature.[10]

About 40-60% of women with GDM have no demonstrable risk factor; for this reason many advocate to screen all women.[11] Typically women with gestational diabetes exhibit no symptoms (another reason for universal screening), but some women may demonstrate increased thirst, increased urination, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, bladder infection, yeast infections and blurred vision.

Screening and diagnosis

A number of screening and diagnostic tests have been used to look for high levels of glucose in plasma or serum in defined circumstances. One method is a stepwise approach where a suspicious result on a screening test is followed by diagnostic test. Alternatively, a more involved diagnostic test can be used directly at the first antenatal visit in high-risk patients (for example in those with polycystic ovarian syndrome or acanthosis nigricans).[6]

Non-challenge blood glucose tests

|

| Screening glucose challenge test |

| Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) |

Non-challenge blood glucose tests involve measuring glucose levels in blood samples without challenging the subject with glucose solutions. A blood glucose levels is determined when fasting, 2 hours after a meal, or simply at any random time. In contrast challenge tests involve drinking a glucose solution and measuring glucose concentration therafter in the blood; in diabetes they tend to remain high. The glucose solution have a very sweet taste that some women find unpleasant; sometimes therefore artificial flavours are added. Some women may experience nausea during the test, and more so with higher glucose levels.[12][13]

Screening pathways

There are different opinions about optimal screening and diagnostic measures, in part due to differences in population risks, cost-effectiveness considerations, and lack of an evidence base to support large national screening programs.[14] The most elaborate regime entails a random blood glucose test during a booking visit, a screening glucose challenge test around 24-28 weeks' gestation, followed by an OGTT if the tests are outside normal limits. If there is a high suspicion, women may be tested earlier.[3]

In the United States, most obstetricians prefer universal screening with a screening glucose tolerance test.[15] In the United Kingdom, obstetric units often rely on risk factors and a random blood glucose test.[16][6] The American Diabetes Association and the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada recommend routine screening unless the patient is low risk (this means the woman must be younger than 25 years and have a body mass index less than 27, with no personal, ethnic or family risk factors)[3][14] The Canadian Diabetes Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend universal screening.[17][18] The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force found that there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against routine screening.[19]

Non-challenge blood glucose tests

When a plasma glucose level is found to be higher than 126 mg/dl (7.0 mmol/l) after fasting, or over 200 mg/dl (11.1 mmol/l) on any occasion, and if this is confirmed on a subsequent day, the diagnosis of GDM is made, and no further testing is required.[3] These tests are typically performed at the first antenatal visit. They are patient-friendly and inexpensive, but have a lower test performance compared to the other tests, with moderate sensitivity, low specificity and high false positive rates.[20][21][22]

Screening glucose challenge test

The screening glucose challenge test is performed between 24-28 weeks, and can be seen as a simplified version of the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). It involves drinking a solution containing 50 grams of glucose, and measuring blood levels 1 hour later.[23]

If the cut-off point is set at 140 mg/dl (7.8 mmol/l), 80% of women with GDM will be detected.[3] If this threshold for further testing is lowered to 130 mg/dl, 90% of GDM cases will be detected, but there will also be more women who will be subjected to a consequent OGTT unnecessarily.

Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)

The OGTT[24] should be done in the morning after an overnight fast of between 8 and 14 hours. During the three previous days the subject must have an unrestricted diet (containing at least 150 g carbohydrate per day) and unlimited physical activity. The subject should remain seated during the test and should not smoke throughout the test.

The test involves drinking a solution containing a certain amount of glucose, and drawing blood to measure glucose levels at the start and on set time intervals thereafter.

The diagnostic criteria from the National Diabetes Data Group (NDDG) have been used most often, but some centers rely on the Carpenter and Coustan criteria, which set the cutoff for normal at lower values. Compared with the NDDG criteria, the Carpenter and Coustan criteria lead to a diagnosis of gestational diabetes in 54 percent more pregnant women, with an increased cost and no compelling evidence of improved perinatal outcomes.[25]

The following are the values which the American Diabetes Association considers to be abnormal during the 100 g of glucose OGTT:

- Fasting blood glucose level ≥95 mg/dl (5.33 mmol/L)

- 1 hour blood glucose level ≥180 mg/dl (10 mmol/L)

- 2 hour blood glucose level ≥155 mg/dl (8.6 mmol/L)

- 3 hour blood glucose level ≥140 mg/dl (7.8 mmol/L)

An alternative test uses a 75 g glucose load and measures the blood glucose levels before and after 1 and 2 hours, using the same reference values. This test will identify less women who are at risk, and there is only a weak concordance (agreement rate) between this test and a 3 hour 100 g test.[26]

The glucose values used to detect gestational diabetes were first determined by O'Sullivan and Mahan (1964) in a retrospective cohort study (using a 100 grams of glucose OGTT) designed to detect risk of developing type 2 diabetes in the future. The values were set using whole blood and required two values reaching or exceeding the value to be positive. [27] Subsequent information led to alterations in O'Sullivan's criteria. When methods for blood glucose determination changed from the use of whole blood to venous plasma samples, the criteria for GDM were also changed.

Urinary glucose testing

Women with GDM may have high glucose levels in their urine (glucosuria). Although dipstick testing is widely practiced, it performs poorly, and discontinuing routine dipstick testing has not been shown to cause underdiagnosis where universal screening is performed.[28] Increased glomerular filtration rates during pregnancy contribute to some 50% of women having glucose in their urine on dipstick tests at some point during their pregnancy. The sensitivity of glucosuria for GDM in the first 2 trimesters is only around 10% and the positive predictive value is around 20%.[29][30]

Complications

GDM poses a risk to mother and child. This risk is largely related to high blood glucose levels and its consequences. The risk increases with higher blood glucose levels.[31] Treatment resulting in better control of these levels can reduce some of the risks of GDM considerably.[32]

The two main risks GDM imposes on the baby are growth abnormalities and chemical imbalances after birth, which may require admission to a neonatal intensive care unit. Infants born to mothers with GDM are at risk of being both large for gestational age (macrosomic)[31] and small for gestational age. Macrosomia in turn increases the risk of instrumental deliveries (e.g. forceps, ventouse and caesarean section) or problems during vaginal delivery (such as shoulder dystocia). Macrosomia may affect 12% of normal women compared to 20% of patients with GDM.[6] However, the evidence for each of these complications is not equally strong; in the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study for example, there was an increased risk for babies to be large but not small for gestational age.[31] Research into complications for GDM is difficult because of the many confounding factors (such as obesity). Labelling a woman as having GDM may in itself increase the risk of having a caesarean section.[33][34]

Neonates are also at an increased risk of low blood glucose (hypoglycemia), jaundice, high red blood cell mass (polycythemia) and low blood calcium (hypocalcemia) and magnesium (hypomagnesemia).[35] GDM also interferes with maturation, causing dysmature babies prone to respiratory distress syndrome due to incomplete lung maturation and impaired surfactant synthesis.[35]

Unlike pre-gestational diabetes, gestational diabetes has not been clearly shown to be an independent risk factor for birth defects. Birth defects usually originate sometime during the first trimester (before the 13th week) of pregnancy, whereas GDM gradually develops and is least pronounced during the first trimester. Studies have shown that the offspring of women with GDM are at a higher risk for congenital malformations.[36][37][38] A large case-control study found that gestational diabetes was linked with a limited group of birth defects, and that this association was generally limited to women with a higher body mass index (≥ 25 kg/m²).[39] It is difficult to make sure that this is not partially due to the inclusion of women with pre-existent type 2 diabetes who were not diagnosed before pregnancy.

Because of conflicting studies, it is unclear at the moment whether women with GDM have a higher risk of preeclampsia.[40] In the HAPO study, the risk of preeclampsia was between 13% and 37% higher, although not all possible confounding factors were corrected.[31]

Prognosis

Gestational diabetes generally resolves once the baby is born. Based on different studies, the chances of developing GDM in a second pregnancy are between 30 and 84%, depending on ethnic background. A second pregnancy within 1 year of the previous pregnancy has a high rate of recurrence.[41]

Women diagnosed with gestational diabetes have an increased risk of developing diabetes mellitus in the future. The risk is highest in women who needed insulin treatment, had antibodies associated with diabetes (such as antibodies against glutamate decarboxylase, islet cell antibodies and/or insulinoma antigen-2), women with more than two previous pregnancies, and women who were obese (in order of importance).[42][43] Women requiring insulin to manage gestational diabetes have a 50% risk of developing diabetes within the next five years.[27] Depending on the population studied, the diagnostic criteria and the length of follow-up, the risk can vary enormously.[44] The risk appears to be highest in the first 5 years, reaching a plateau thereafter.[44] One of the longest studies followed a group of women from Boston, Massachusetts; half of them developed diabetes after 6 years, and more than 70% had diabetes after 28 years.[44] In a retrospective study in Navajo women, the risk of diabetes after GDM was estimated to be 50 to 70% after 11 years.[45] Another study found a risk of diabetes after GDM of more than 25% after 15 years.[46] In populations with a low risk for type 2 diabetes, in lean subjects and in patients with auto-antibodies, there is a higher rate of women developing type 1 diabetes.[43]

Children of women with GDM have an increased risk for childhood and adult obesity and an increased risk of glucose intolerance and type 2 diabetes later in life.[47] This risk relates to increased maternal glucose values.[48] It is currently unclear how much genetic susceptibility and environmental factors each contribute to this risk, and if treatment of GDM can influence this outcome.[49]

There are scarce statistical data on the risk of other conditions in women with GDM; in the Jerusalem Perinatal study, 410 out of 37962 patients were reported to have GDM, and there was a tendency towards more breast and pancreatic cancer, but more research is needed to confirm this finding.[50][51]

Classification

The White classification, named after Priscilla White[52] who pioneered in research on the effect of diabetes types on perinatal outcome, is widely used to assess maternal and fetal risk. It distinguishes between gestational diabetes (type A) and diabetes that existed prior to pregnancy (pregestational diabetes). These two groups are further subdivided according to their associated risks and management.[53]

There are 2 subtypes of gestational diabetes (diabetes which began during pregnancy):

- Type A1: abnormal oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) but normal blood glucose levels during fasting and 2 hours after meals; diet modification is sufficient to control glucose levels

- Type A2: abnormal OGTT compounded by abnormal glucose levels during fasting and/or after meals; additional therapy with insulin or other medications is required

The second group of diabetes which existed prior to pregnancy is also split up into several subtypes.

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to reduce the risks of GDM for mother and child. Scientific evidence is beginning to show that controlling glucose levels can result in less serious fetal complications (such as macrosomia) and increased maternal quality of life. Unfortunately, treatment of GDM is also accompanied by more infants admitted to neonatal wards and more inductions of labour, with no proven decrease in cesarean section rates or perinatal mortality.[54][55] These findings are still recent and controversial.[56]

Counselling before pregnancy (for example, about preventive folic acid supplements) and multidisciplinary management are important for good pregnancy outcomes.[57] Most women can manage their GDM with dietary changes and exercise. Self monitoring of blood glucose levels can guide therapy. Some women will need antidiabetic drugs, most commonly insulin therapy.

Any diet needs to provide sufficient calories for pregnancy, typically 2,000 - 2,500 kcal with the exclusion of simple carbohydrates.[11] The main goal of dietary modifications is to avoid peaks in blood sugar levels. This can be done by spreading carbohydrate intake over meals and snacks throughout the day, and using slow-release carbohydrate sources. Since insulin resistance is highest in mornings, breakfast carbohydrates need to be restricted more.[7]

Regular moderately intense physical exercise is advised, although there is no consensus on the specific structure of exercise programs for GDM.[7][58]

Self monitoring can be accomplished using a handheld capillary glucose dosage system. Compliance with these glucometer systems can be low.[32] Target ranges advised by the Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society are as follows:[7]

- fasting capillary blood glucose levels <5.5 mmol/L

- 1 hour postprandial capillary blood glucose levels <8.0 mmol/L

- 2 hour postprandial blood glucose levels <6.7 mmol/L

Regular blood samples can be used to determine HbA1c levels, which give an idea of glucose control over a longer time period.[7]

If monitoring reveals failing control of glucose levels with these measures, or if there is evidence of complications like excessive fetal growth, treatment with insulin might become necessary. The most common therapeutic regime involves premeal fast-acting insulin to blunt sharp glucose rises after meals.[7] Care needs to be taken to avoid low blood sugar levels (hypoglycemia) due to excessive insulin injections. Insulin therapy can be normal or very thight; more injections can result in better control but requires more effort, and there is no consensus that it has large benefits.[6][59][60]

There is some evidence that certain oral glycemic agents might be safe in pregnancy, or at least, are significantly less dangerous to the developing fetus than poorly controlled diabetes. However, few studies have been performed as of this time and this is not a generally accepted treatment. These agents may be used in research settings, or if the patient needs intervention but refuses insulin therapy, and is aware of the risks.[7] Glyburide, a second generation sulfonylurea, has been shown to be an effective alternative to insulin therapy.[61][62] In one study, 4% of women needed supplemental insulin to reach blood sugar targets.[62]

Metformin has shown promising results. Treatment of polycystic ovarian syndrome with metformin during pregnancy has been noted to decrease GDM levels.[63] A recent randomized controlled trial of metformin versus insulin showed that women preferred metformin tablets to insulin injections, and that metformin is safe and equally effective as insulin.[64] Severe neonatal hypoglycemia was less common in insulin-treated women, but preterm delivery was more common. Almost half of patients did not reach sufficient control with metformin alone and needed supplemental therapy with insulin; compared to those treated with insulin alone, they required less insulin, and they gained less weight.[64] There remains a possibility of long-term complications from metformin therapy, although follow-up at the age of 18 months of children born to women with polycystic ovarian syndrome and treated with metformin revealed no developmental abnormalities.[65]

If diet, exercise, and oral medication are inadequate to control glucose levels, insulin therapy may become necessary.

The development of macrosomia can be evaluated during pregnancy by using sonography. Women who use insulin, with a history of stillbirth, or with hypertension are managed like women with ouvert diabetes.[11]

Research suggests a possible benefit of breastfeeding to reduce the risk of diabetes and related risks for both mother and child.[66]

A repeat OGTT should be carried out 2-4 months after delivery, to confirm the diabetes has disappeared. Afterwards, regular screening for type 2 diabetes is advised.[7]

Controversy

Gestational diabetes is a controversial subject. Some critics question whether GDM is a disease in its own right. Labelling women as 'suffering from GDM' seems to predispose them to more interventions (like cesarean sections and induction) for perceived increased risks,[33][34] while treatment of GDM has not been proven to affect perinatal mortality or caesarean section rates.[54] Lack of reproduceability of glucose tolerance testing is another problematic area.[67]

See also

- Diabetes mellitus and pregnancy

Footnotes

- ↑ Thomas R Moore, MD et al. Diabetes Mellitus and Pregnancy. med/2349 at eMedicine. Version: Jan 27, 2005 update.

- ↑ Metzger BE, Coustan DR (Eds.). Proceedings of the Fourth International Work-shop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 1998; 21 (Suppl. 2): B1–B167.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 American Diabetes Association. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: S88-90. PMID 14693936

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Carr DB, Gabbe S. Gestational Diabetes: Detection, Management, and Implications. Clin Diabetes 1998; 16(1): 4.

- ↑ Buchanan TA, Xiang AH. Gestational diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 2005; 115(3): 485–491. PMID 15765129

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Kelly L, Evans L, Messenger D. Controversies around gestational diabetes. Practical information for family doctors. Can Fam Physician 2005; 51: 688-95. PMID 15934273 Full text at PMC: 15934273

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 Ross G. Gestational diabetes. Aust Fam Physician 2006; 35(6): 392-6. PMID 16751853

- ↑ Chu SY, Callaghan WM, Kim SY, Schmid CH, Lau J, England LJ, Dietz PM. Maternal obesity and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2007; 30(8): 2070-6. PMID 17416786

- ↑ England LJ, Levine RJ, Qian C, et. al. Glucose tolerance and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus in nulliparous women who smoke during pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol 2004; 160(12): 1205-13. PMID 15583373

- ↑ Ma RM, Lao TT, Ma CL, et. al. Relationship between leg length and gestational diabetes mellitus in Chinese pregnant women. Diabetes Care 2007; 30(11): 2960-1. PMID 17666468

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 ACOG. Precis V. An Update on Obstetrics and Gynecology.. ACOG (1994). p. 170.

- ↑ Sievenpiper JL, Jenkins DJ, Josse RG, Vuksan V. Dilution of the 75-g oral glucose tolerance test improves overall tolerability but not reproducibility in subjects with different body compositions. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2001; 51(2): 87-95. PMID 11165688

- ↑ Reece EA, Holford T, Tuck S, Bargar M, O'Connor T, Hobbins JC. Screening for gestational diabetes: one-hour carbohydrate tolerance test performed by a virtually tasteless polymer of glucose. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1987; 156(1): 132-4. PMID 3799747

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Berger H, Crane J, Farine D, et. al. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2002; 24: 894–912. PMID 12417905

- ↑ Gabbe SG, Gregory RP, Power ML, Williams SB, Schulkin J. Management of diabetes mellitus by obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2004; 103(6): 1229-34. PMID 15172857

- ↑ Mires GJ, Williams FL, Harper V. Screening practices for gestational diabetes mellitus in UK obstetric units. Diabet Med 1999; 16(2): 138-41. PMID 10229307

- ↑ Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Canadian Diabetes Association 2003 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Diabetes in Canada. Can J Diabetes 2003; 27 (Suppl 2): 1–140.

- ↑ Gabbe SG, Graves CR. Management of diabetes mellitus complicating pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2003; 102(4): 857-68. PMID 14551019

- ↑ Hillier TA, Vesco KK, Pedula KL, Beil TL, Whitlock EP, Pettitt DJ (May 2008). "Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force". Ann. Intern. Med. 148 (10): 766–75. PMID 18490689. http://www.annals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18490689.

- ↑ Agarwal MM, Dhatt GS. Fasting plasma glucose as a screening test for gestational diabetes mellitus. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2007; 275(2): 81-7. PMID 16967273

- ↑ Sacks DA, Chen W, Wolde-Tsadik G, Buchanan TA. Fasting plasma glucose test at the first prenatal visit as a screen for gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol 2003; 101(6): 1197-203. PMID 12798525

- ↑ Agarwal MM, Dhatt GS, Punnose J, Zayed R. Gestational diabetes: fasting and postprandial glucose as first prenatal screening tests in a high-risk population. J Reprod Med 2007; 52(4): 299-305. PMID 17506370

- ↑ "What I need to know about Gestational Diabetes". National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse. National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse (2006). Retrieved on 2006-11-27.

- ↑ Glucose tolerance test. MedlinePlus, November 8, 2006.

- ↑ Carpenter MW, Coustan DR. Criteria for screening tests for gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1982; 144(7): 768-73. PMID 83071919

- ↑ Mello G, Elena P, Ognibene A, Cioni R, Tondi F, Pezzati P, Pratesi M, Scarselli G, Messeri G. Lack of concordance between the 75-g and 100-g glucose load tests for the diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus. Clin Chem 2006; 52(9): 1679-84. PMID 16873295

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Gestational Diabetes". Diabetes Mellitus & Pregnancy - Gestational Diabetes. Armenian Medical Network (2006). Retrieved on 2006-11-27.

- ↑ Rhode MA, Shapiro H, Jones OW 3rd. Indicated vs. routine prenatal urine chemical reagent strip testing. J Reprod Med 2007; 52(3): 214-9. PMID 17465289

- ↑ Alto WA. No need for glycosuria/proteinuria screen in pregnant women. J Fam Pract 2005; 54(11): 978-83. PMID 16266604

- ↑ Ritterath C, Siegmund T, Rad NT, Stein U, Buhling KJ. Accuracy and influence of ascorbic acid on glucose-test with urine dip sticks in prenatal care. J Perinat Med 2006; 34(4): 285-8. PMID 16856816

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):1991-2002. PMID 18463375

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Langer O, Rodriguez DA, Xenakis EM, McFarland MB, Berkus MD, Arrendondo F. Intensified versus conventional management of gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994; 170(4): 1036-46. PMID 8166187

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Naylor CD, Sermer M, Chen E, Farine D. Selective screening for gestational diabetes mellitus. Toronto Trihospital Gestational Diabetes Project Investigators. N Engl J Med 1997; 337(22): 1591–1596. PMID 9371855

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Jovanovic-Peterson L, Bevier W, Peterson CM. The Santa Barbara County Health Care Services program: birth weight change concomitant with screening for and treatment of glucose-intolerance of pregnancy: a potential cost-effective intervention? Am J Perinatol 1997; 14(4): 221-8. PMID 9259932

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Jones CW. Gestational diabetes and its impact on the neonate. Neonatal Netw. 2001;20(6):17-23. PMID 12144115

- ↑ Allen VM, Armson BA, Wilson RD, et al. Teratogenicity associated with pre-existing and gestational diabetes. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2007; 29(11): 927-34. PMID 17977497

- ↑ Martínez-Frías ML, Frías JP, Bermejo E, Rodríguez-Pinilla E, Prieto L, Frías JL. Pre-gestational maternal body mass index predicts an increased risk of congenital malformations in infants of mothers with gestational diabetes. Diabet Med 2005; 22(6): 775-81. PMID 15910631

- ↑ Savona-Ventura C, Gatt M. Embryonal risks in gestational diabetes mellitus. Early Hum Dev 2004; 79(1): 59-63. PMID 15449398

- ↑ Correa A, Gilboa SM, Besser LM, et al (September 2008). "Diabetes mellitus and birth defects". American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 199 (3): 237.e1–9. doi:. PMID 18674752. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0002-9378(08)00639-X.

- ↑ Leguizamón GF, Zeff NP, Fernández A. Hypertension and the pregnancy complicated by diabetes. Curr Diab Rep 2006; 6(4): 297-304. PMID 16879782

- ↑ Kim C, Berger DK, Chamany S. Recurrence of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Diabetes Care 2007; 30(5): 1314-9. PMID 17290037

- ↑ Löbner K, Knopff A, Baumgarten A, et. al. Predictors of postpartum diabetes in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 2006; 55(3): 792-7. PMID 16505245

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Järvelä IY, Juutinen J, Koskela P et. al. Gestational diabetes identifies women at risk for permanent type 1 and type 2 diabetes in fertile age: predictive role of autoantibodies. Diabetes Care 2006; 29(3): 607-12. PMID 16505514

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Kim C, Newton KM, Knopp RH. Gestational diabetes and the incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(10):1862-8. PMID 12351492

- ↑ Lee AJ, Hiscock RJ, Wein P, Walker SP, Permezel M. Gestational diabetes mellitus: clinical predictors and long-term risk of developing type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study using survival analysis. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(4):878-83. PMID 17392549

- ↑ Boney CM, Verma A, Tucker R, Vohr BR. Metabolic syndrome in childhood: association with birth weight, maternal obesity, and gestational diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics 2005; 115(3): e290-6. PMID 15741354

- ↑ Hillier TA, Pedula KL, Schmidt MM, Mullen JA, Charles MA, Pettitt DJ. Childhood obesity and metabolic imprinting: the ongoing effects of maternal hyperglycemia. Diabetes Care 2007; 30(9): 2287-92. PMID 17519427

- ↑ Metzger BE. Long-term Outcomes in Mothers Diagnosed With Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Their Offspring. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2007; 50(4): 972-9. PMID 17982340

- ↑ Perrin MC, Terry MB, Kleinhaus K, et. al. Gestational diabetes and the risk of breast cancer among women in the Jerusalem Perinatal Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2007 [Epub]. PMID 17476589

- ↑ Perrin MC, Terry MB, Kleinhaus K, et. al. Gestational diabetes as a risk factor for pancreatic cancer: a prospective cohort study. BMC Med 2007; 5: 25. Full text at PMC: 17705823

- ↑ White P. Pregnancy complicating diabetes. Am J Med 1949; 7: 609. PMID 15396063

- ↑ Gabbe S.G., Niebyl J.R., Simpson J.L. OBSTETRICS: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. Fourth edition. Churchill Livingstone, New York, 2002. ISBN 0-443-06572-1

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR et. al, Australian Carbohydrate Intolerance Study in Pregnant Women (ACHOIS) Trial Group. Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 2005; 352(24): 2477-86. PMID 15951574

- ↑ Sermer M, Naylor CD, Gare DJ et al. Impact of increasing carbohydrate intolerance on maternal-fetal outcomes in 3637 women without gestational diabetes. The Toronto Tri-Hospital Gestational Diabetes Project. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995; 173(1): 146-56. PMID 7631672

- ↑ Tuffnell DJ, West J, Walkinshaw SA. Treatments for gestational diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD003395. PMID 12917965

- ↑ Kapoor N, Sankaran S, Hyer S, Shehata H. Diabetes in pregnancy: a review of current evidence. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2007; 19(6): 586-590. PMID 18007138

- ↑ Mottola MF. The role of exercise in the prevention and treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus. Curr Sports Med Rep 2007; 6(6): 381-6. PMID 18001611

- ↑ Nachum Z, Ben-Shlomo I, Weiner E, Shalev E. Twice daily versus four times daily insulin dose regimens for diabetes in pregnancy: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 1999; 319(7219): 1223-7.

- ↑ Walkinshaw SA. Very tight versus tight control for diabetes in pregnancy (WITHDRAWN). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; (2): CD000226. PMID 17636623

- ↑ Kremer CJ, Duff P. Glyburide for the treatment of gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004; 190(5): 1438-9. PMID 15167862

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Langer O, Conway DL, Berkus MD, Xenakis EM, Gonzales O. A comparison of glyburide and insulin in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(16):1134-8. PMID 11036118

- ↑ Simmons D, Walters BN, Rowan JA, McIntyre HD. Metformin therapy and diabetes in pregnancy. Med J Aust 2004; 180(9): 462-4. PMID 15115425

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Rowan JA, Hague WM, Gao W, Battin MR, Moore MP; MiG Trial Investigators. Metformin versus insulin for the treatment of gestational diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):2003-15. PMID 18463376

- ↑ Glueck CJ, Goldenberg N, Pranikoff J, Loftspring M, Sieve L, Wang P. Height, weight, and motor-social development during the first 18 months of life in 126 infants born to 109 mothers with polycystic ovary syndrome who conceived on and continued metformin through pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(6):1323-30. PMID 15117896

- ↑ Taylor JS, Kacmar JE, Nothnagle M, Lawrence RA. A systematic review of the literature associating breastfeeding with type 2 diabetes and gestational diabetes. J Am Coll Nutr 2005; 24(5): 320-6. PMID 16192255

- ↑ Murray Enkin, Marc J.N.C. Keirse, James Neilson, et al. A Guide to Effective Care in Pregnancy and Childbirth: Chapter 11: Gestational Diabetes (requires login). Oxford University Press, 2000.

External links

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development - Am I at Risk for Gestational Diabetes?

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development - Managing Gestational Diabetes: A Patient's Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy

- Gestational Diabetes Resource Guide - American Diabetes Association

- MSN Health: Gestational Diabetes

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||