Gestalt psychology

Portal • History

Areas |

| RESEARCH |

|

Abnormal |

| APPLIED |

|

Clinical |

| LISTS |

|

Publications |

Gestalt psychology (also Gestalt of the Berlin School) is a theory of mind and brain that proposes that the operational principle of the brain is holistic, parallel, and analog, with self-organizing tendencies; or, that the whole is different from the sum of its parts. The Gestalt effect refers to the form-forming capability of our senses, particularly with respect to the visual recognition of figures and whole forms instead of just a collection of simple lines and curves. The word Gestalt in German literally means "shape" or "figure."

Contents |

Origins

Although Max Wertheimer is credited as the founder of the movement, the concept of Gestalt was first introduced in contemporary philosophy and psychology by Christian von Ehrenfels (a member of the School of Brentano). The idea of Gestalt has its roots in theories by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Immanuel Kant, and Ernst Mach. Wertheimer's unique contribution was to insist that the "Gestalt" is perceptually primary, defining the parts of which it was composed, rather than being a secondary quality that emerges from those parts, as von Ehrenfels's earlier Gestalt-Qualität had been.

Both von Ehrenfels and Edmund Husserl seem to have been inspired by Mach's work Beiträge zur Analyse der Empfindungen (Contributions to the Analysis of the Sensations, 1886), in formulating their very similar concepts of Gestalt and Figural Moment, respectively.

Early 20th century theorists, such as Kurt Koffka, Max Wertheimer, and Wolfgang Köhler (students of Carl Stumpf) saw objects as perceived within an environment according to all of their elements taken together as a global construct. This 'gestalt' or 'whole form' approach sought to define principles of perception -- seemingly innate mental laws which determined the way in which objects were perceived.

These laws took several forms, such as the grouping of similar, or proximate, objects together, within this global process. Although Gestalt has been criticized for being merely descriptive, it has formed the basis of much further research into the perception of patterns and objects (ref: Carlson, Buskist & Martin, 2000), and of research into behavior, thinking, problem solving and psychopathology.

Theoretical framework and methodology

The investigations developed at the beginning of the 20th century, based on traditional scientific methodology, divided the object of study into a set of elements that could be analyzed separately with the objective of reducing the complexity of this object. Contrary to this methodology, the school of Gestalt practiced a series of theoretical and methodological principles that attempted to redefine the approach to psychological research.

The theoretical principles are the following:

- Principle of Totality - The conscious experience must be considered globally (by taking into account all the physical and mental aspects of the individual simultaneously) because the nature of the mind demands that each component be considered as part of a system of dynamic relationships.

- Principle of psychophysical isomorphism - A correlation exists between conscious experience and cerebral activity.

Based on the principles above the following methodological principles are defined:

- Phenomenon Experimental Analysis - In relation to the Totality Principle any psychological research should take as a starting point phenomena and not be solely focused on sensory qualities.

- Biotic Experiment - The School of Gestalt established a need to conduct real experiments which sharply contrasted with and opposed classic laboratory experiments. This signified experimenting in natural situations, developed in real conditions, in which it would be possible to reproduce, with higher fidelity, what would be habitual for a subject.

Properties

The key principles of Gestalt systems are emergence, reification, multistability and invariance.[1]

Emergence

Emergence is demonstrated by the perception of the Dog Picture, which depicts a Dalmatian dog sniffing the ground in the shade of overhanging trees. The dog is not recognized by first identifying its parts (feet, ears, nose, tail, etc.), and then inferring the dog from those component parts. Instead, the dog is perceived as a whole, all at once. However, this is a description of what occurs in vision and not an explanation. Gestalt theory does not explain how the percept of a dog emerges.

Reification

Reification is the constructive or generative aspect of perception, by which the experienced percept contains more explicit spatial information than the sensory stimulus on which it is based.

For instance, a triangle will be perceived in picture A, although no triangle has actually been drawn. In pictures B and D the eye will recognize disparate shapes as "belonging" to a single shape, in C a complete three-dimensional shape is seen, where in actuality no such thing is drawn.

Reification can be explained by progress in the study of illusory contours, which are treated by the visual system as "real" contours.

See also: Reification (fallacy)

Multistability

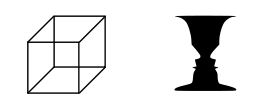

Multistability (or multistable perception) is the tendency of ambiguous perceptual experiences to pop back and forth unstably between two or more alternative interpretations. This is seen for example in the Necker cube, and in Rubin's Figure / Vase illusion shown to the left. Other examples include the 'three-pronged widget' and artist M. C. Escher's artwork and the appearance of flashing marquee lights moving first one direction and then suddenly the other. Again, Gestalt does not explain how images appear multistable, only that they do.

Invariance

Invariance is the property of perception whereby simple geometrical objects are recognized independent of rotation, translation, and scale; as well as several other variations such as elastic deformations, different lighting, and different component features. For example, the objects in A in the figure are all immediately recognized as the same basic shape, which are immediately distinguishable from the forms in B. They are even recognized despite perspective and elastic deformations as in C, and when depicted using different graphic elements as in D. Computational theories of vision, such as those by David Marr, have had more success in explaining how objects are classified.

Emergence, reification, multistability, and invariance are not separable modules to be modeled individually, but they are different aspects of a single unified dynamic mechanism.

Prägnanz

The fundamental principle of gestalt perception is the law of prägnanz (German for conciseness) which says that we tend to order our experience in a manner that is regular, orderly, symmetric, and simple. Gestalt psychologists attempt to discover refinements of the law of prägnanz, and this involves writing down laws which hypothetically allow us to predict the interpretation of sensation, what are often called "gestalt laws".[1] These include:

- Law of Closure — The mind may experience elements it does not perceive through sensation, in order to complete a regular figure (that is, to increase regularity).

- Law of Similarity — The mind groups similar elements into collective entities or totalities. This similarity might depend on relationships of form, color, size, or brightness.

- Law of Proximity — Spatial or temporal proximity of elements may induce the mind to perceive a collective or totality.

- Law of Symmetry (Figure ground relationships)— Symmetrical images are perceived collectively, even in spite of distance.

- Law of Continuity — The mind continues visual, auditory, and kinetic patterns.

- Law of Common Fate — Elements with the same moving direction are perceived as a collective or unit.

Gestalt views in psychology

Gestalt psychologists find it is important to think of problems as a whole. Max Wertheimer considered thinking to happen in two ways: productive and reproductive.[1]

Productive thinking- is solving a problem with insight.

This is a quick insightful unplanned response to situations and environmental interaction.

Reproductive thinking-is solving a problem with previous experiences and what is already known. (1945/1959).

This is a very common thinking. For example, when a person is given several segments of information, he/she deliberately examines the relationships among its parts, analyzes their purpose, concept, and totality, he/she reaches the "aha!" moment, using what is already known. Understanding in this case happens intentionally by reproductive thinking.

Other Gestalts psychologist Perkins believes insight deals with three processes:

1) Unconscious leap in thinking. [1].

2) The increased amount of speed in mental processing.

3) The amount of short-circuiting which occurs in normal reasoning. [2]

Other views going against the Gestalt psychology are:

1) Nothing-Special View

2) Neo-Gestalts View

3) The Three-Process View

Gestalt laws continue to play an important role in current psychological research on vision. For example, the object-based attention hypothesis[3] states that elements in a visual scene are first grouped according to Gestalt principles; consequently, further attentional resources can be allocated to particular objects.

Gestalt psychology should not be confused with the Gestalt therapy of Fritz Perls, which is only peripherally linked to Gestalt psychology. A strictly Gestalt psychology-based therapeutic method is Gestalt Theoretical Psychotherapy, developed by the German Gestalt psychologist and psychotherapist Hans-Jürgen Walter.

Applications in computer science

The Gestalt laws are used in user interface design. The laws of similarity and proximity can, for example, be used as guides for placing radio buttons. They may also be used in designing computers and software for more intuitive human use. Examples include the design and layout of a desktop's shortcuts in rows and columns. Gestalt psychology also has applications in computer vision for trying to make computers "see" the same things as humans do.

Criticism

In some scholarly communities (for example, cognitive psychology and computational neuroscience), Gestalt theories of perception are criticized for being descriptive rather than explanatory in nature. For this reason, they are viewed by some as redundant or uninformative. For example, Bruce, Green & Georgeson[4] conclude the following regarding Gestalt theory's influence on the study of visual perception:

- "The physiological theory of the Gestaltists has fallen by the wayside, leaving us with a set of descriptive principles, but without a model of perceptual processing. Indeed, some of their "laws" of perceptual organisation today sound vague and inadequate. What is meant by a "good" or "simple" shape, for example?"

In other fields, such as perceptual psychology and visual display design, Gestalt principles continue to be used and discussed today as a predictive model of human behaviour.

See also

- Gestalt therapy

- Structural information theory

- Rudolf Arnheim

- Wolfgang Metzger

- Kurt Goldstein

- Solomon Asch

- Fritz Perls

- James Tenney

- Graz School

- Important publications in gestalt psychology

- Mereology

- Optical illusion

- Pattern recognition (psychology)

- Pattern recognition (machine learning)

- Notan

- Amodal perception

External links

- Gestalt Society of Croatia

- International Society for Gestalt Theory and its Applications - GTA

- Art, Design and Gestalt Theory

- Rudolf Arnheim: The Little Owl on the Shoulder of Athene

- Embedded Figures in Art, Architecture and Design

- On Max Wertheimer and Pablo Picasso

- On Esthetics and Gestalt Theory

- The World In Your Head - by Steven Lehar

- Gestalt Isomorphism and the Primacy of Subjective Conscious Experience - by Steven Lehar

- The new gestalt psychology of the 21st century

- The Pennsylvania Gestalt Center

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Sternberg, Robert, Cognitive Psychology Third Edition, Thomson Wadsworth© 2003.

- ↑ Langley& associates, 1987; Perkins, 1981; Weisberg, 1986,1995”>

- ↑ Scholl, B. J. (2001). Objects and attention: The state of the art. Cognition, 80(1-2), 1-46.

- ↑ Bruce, V., Green, P. & Georgeson, M. (1996). Visual perception: Physiology, psychology and ecology (3rd ed.). LEA. pp. 110.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||