Georgy Zhukov

| Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov | |

|---|---|

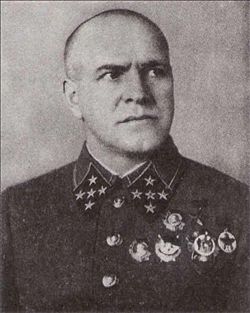

Georgy Zhukov, as a General, in 1940. |

|

| Place of birth | Strelkovka, Kaluga, Russian Empire |

| Place of death | Moscow, Soviet Union |

| Resting place | Kremlin Wall Necropolis |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | Russian Imperial Army Red Army |

| Years of service | 1915 — 1957 |

| Rank | Marshal of the Soviet Union |

| Commands held | Red Army |

| Battles/wars | World War I Russian Civil War Great Patriotic War |

| Awards | Hero of the Soviet Union (4) Order of Lenin (4) Order of the Red Banner (3) Order of Suvorov, 1st Class (2) Order of Victory (2) Virtuti Militari Order of the Bath Legion of Merit Cross of St. George (2) |

| Other work | Memoirs: Remembrances and Contemplations, 1969. |

Marshal of the Soviet Union Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov, GCB (Russian: Гео́ргий Константи́нович Жу́ков) (December 1 [O.S. November 19] 1896 – June 18, 1974) was a Soviet military commander who, in the course of World War II, played an important role in leading the Red Army to liberate the Soviet Union from the Axis Powers' occupation, to advance through much of Eastern Europe, and to conquer Germany's capital, Berlin. He is one of the most decorated heroes in the history of both Russia and the Soviet Union.

Contents |

Career before World War II

Born into a poverty-stricken peasant family in Strelkovka, Maloyaroslavets Uyezd, Kaluga Guberniya (now merged into the town of Zhukov in Zhukovo Raion Kaluga Oblast), Zhukov was apprenticed to work as a furrier in Moscow, and in 1915 was conscripted into the army of the Russian Empire, where he served first in the 106th Reserve Cavalry Regiment, then the 10th Dragoon Novgorod Regiment[1][2]. During World War I, Zhukov was awarded the Cross of St. George twice and promoted to the rank of non-commissioned officer for his bravery in battle. He joined the Bolshevik Party after the October Revolution, and his background of poverty became an asset. After recovering from typhus he fought in the Russian Civil War from 1918 to 1921, at one time within 1st Cavalry Army. He received the Order of the Battle Red Banner for subduing the Tambov rebellion in 1921.[3]

By 1923 Zhukov was commander of a regiment, and in 1930 of a brigade. He was a keen proponent of the new theory of armoured warfare and was noted for his detailed planning, tough discipline and strictness, and a "never give up" attitude. He survived Joseph Stalin's Great Purge of the Red Army command in 1937-39.

In 1938 Zhukov was directed to command the First Soviet Mongolian Army Group, and saw action against Japan's Kwantung Army on the border between Mongolia and the Japanese controlled state of Manchukuo in an undeclared war that lasted from 1938 to 1939. What began as a routine border skirmish—the Japanese testing the resolve of the Soviets to defend their territory—rapidly escalated into a full-scale war, the Japanese pushing forward with 80,000 troops, 180 tanks and 450 aircraft.

This led to the decisive Battle of Khalkhin Gol. Zhukov requested major reinforcements and on August 15, 1939 he ordered what seemed at first to be a conventional frontal attack. However, he had held back two tank brigades, which in a daring and successful manoeuver he ordered to advance around both flanks of the battle. Supported by motorized artillery and infantry, the two mobile battle groups encircled the 6th Japanese army and captured their vulnerable supply areas. Within a few days the Japanese troops were defeated.

For this operation Zhukov was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. Outside of the Soviet Union, however, this battle remained little-known as by this time World War II had begun. Zhukov's pioneering use of mobile armour went unheeded by the West, and in consequence the German Blitzkrieg against France in 1940 came as a great surprise.

Promoted to full general in 1940, Zhukov was briefly (January - July 1941) chief of the Red Army General Staff before a disagreement with Stalin led to him being replaced by Marshal Boris Shaposhnikov (who was in turn replaced by Aleksandr Vasilevsky in 1942). Coincidentally, this led to a relative non-accountability of Zhukov's military role in the huge territorial losses during the German 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union thus ensuring his presence "in the wings" for Stalingrad. The question of how much he could have done had he held command earlier is still much discussed.

Public perception

According to his own memoirs (written after the death of Stalin and during the peak of Nikita Khrushchev's Anti-Stalin campaign), Zhukov was fearless in his direct criticisms of Stalin and other commanders after the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 (see Great Patriotic War). Among Soviet commanders, he was one of the few who attempted to convince Stalin that the Kiev region could not be held and would suffer a double envelopment by the Wehrmacht troops. Stalin, who berated Zhukov and dismissed his advice, refused to evacuate the troops in the area. As a result, half a million troops became prisoners when the Germans took Kiev.[4] Zhukov stopped the German advance in Leningrad's southern outskirts in the autumn of 1941.[5][6]

However, such conventional portrayals of Zhukov are disputed by some contemporary Russian authors. Controversial émigré historian Viktor Suvorov has written two books: The Shadow of the Victory and I Take Back My Words, both of which are highly critical of Zhukov. In the first of these books, Suvorov claims — contrary to the aforementioned historians — that Zhukov accepted Stalin's aforementioned strategy at Kiev in 1941. Suvorov also claims that Zhukov was a poor strategist, because he also accepted Stalin's decision to occupy the Baltic states and Bessarabia. These acts, in Suvorov's estimation, provoked Germany, as they threatened German supplies of strategic goods, including nickel and lumber from Finland and Sweden, and oil from Romania.[7] The Bessarabian incursion also led Romania into the German camp.

Official sources, only made available recently, reveal that Zhukov and his colleagues had been planning a (preemptive) strike against Germany in 1941. A proposal from May 15, 1941[8], widely discussed amongst Russian historians, was first revealed by Hero of the Soviet Union V. V. Karpov, who had access to secret archives. He probably intended to show Zhukov as a military genius, who in the decisive moment had suggested a surprise attack on the enemy. Viktor Suvorov has used the plan to support his thesis and Mikhail Meltyukhov et al. have studied the background, reaching wider conclusions.[9][10] The Memorandum was supposedly presented to Stalin by Commissar of Defense Semyon Timoshenko and Chief of the General Staff Zhukov.

The document is unsigned, but this was rather a rule than exception at the time. It has been disputed whether the plan (demanding a strike against Germany), was approved by Stalin (or whether it was even ever presented to Stalin). Overy suggests that the plan was developed by Zhukov and Timoshenko independently of Stalin, who later rejected it, fearing provoking the Germans. [11] On the other hand, Russian historian Sokolov, supported by Nevezhin and Danilov, taking into account the concentration of decision-making into hands of political leadership, regards it "completely improbable that the highest officers of General Staff could have developed a plan of pre-emptive strike against Germany without Stalin's sanctioning."[12] Meltyukhov has also pointed out the similarities between the May 1941 proposal and Soviet drafts dating back to 1940 [13]

These plans officially suggested repulsion of German aggression and a rapid counterstrike, however, the initial defence phase was not elaborated, leading Boris Sokolov to compare it with the alleged Soviet counter-strike plans in case of "Finnish aggression" in 1939.[14]

The Great Patriotic War

- See also: Eastern Front (World War II)

On June 22, 1941, Zhukov signed the Directive of Peoples' Commissariat of Defence No. 3, which ordered an all-out counteroffensive by Red Army forces: he commanded the troops "to encircle and destroy enemy grouping near Suwałki and to seize the Suwałki region by the evening of 24.6" and "to encircle and destroy the enemy grouping invading in Vladimir-Volynia and Brody direction" and even "to seize the Lublin region by the evening of 24.6"[15] This maneuver failed and disorganized Red Army units were destroyed by the Wehrmacht. Later, Zhukov claimed that he was forced to sign the document by Joseph Stalin, despite the reservations that he raised. [16] This document was supposedly written by Aleksandr Vasilevsky, and Zhukov was forced to sign it.[17]

On July 29, 1941, Zhukov was sacked from his post of Chief of the General Staff because he suggested abandoning Kiev to avoid an encirclement[18] Stalin refused, leading to a stinging Soviet defeat.

In October 1941, when the Germans were closing in on Moscow, Zhukov replaced Semyon Timoshenko in command of the central front and was assigned to direct the Defense of Moscow. He also directed the transfer of troops from the Far East, where a large part of Soviet ground forces had been stationed on the day of Hitler's invasion. The successful Soviet counter-offensive in December 1941 drove the Germans back, out of reach of the Soviet capital. Zhukov's feat of logistics is considered by some to be his greatest achievement.

By now, Zhukov was firmly back in favour and Stalin valued him precisely for his outspokenness. Stalin's (eventual) willingness to submit to criticism and listen to his generals was an important element in the eventual Soviet victory; Hitler, on the other hand, usually dismissed any general who disagreed with him.

In 1942 Zhukov was made Deputy Commander-in-Chief and sent to the south-western front to take charge of the defense of Stalingrad. Under the overall command of Vasilievsky, he oversaw the encirclement and capture of the German Sixth Army in 1943 at the cost of perhaps a million dead (see Battle of Stalingrad). During the operation, Zhukov spent most of the time in fruitless attacks in the direction of Rzhev, Sychevka and Vyazma, known as the "Rzhev meat grinder" ("Ржевская мясорубка"). Some historians now question the casualty figures allegedly suffered by the Soviets at Rzhev as being too high. There is also some new evidence which show the Rzhev operation was a diversion in order to prevent the Germans from successfully breaking the encirclement of Stalingrad.

In January 1943, he orchestrated the first breakthrough of the German blockade of Leningrad. He was a Stavka coordinator at the Battle of Kursk in July 1943, and, according to the memoirs, playing a central role in the planning of the battle and the hugely successful offensive that followed. Kursk was the first major German defeat in summer and has a good claim to be a battle at least as decisive as Stalingrad. Commander of Central Front Konstantin Rokossovsky, however, says that planning and decisions for the Battle of Kursk were made without Zhukov, that he only arrived just before the battle, made no decisions and left soon afterwards, and that Zhukov exaggerated his role (Source: Военно-исторический журнал, 1992 N3 p.31).

Following the failure of Marshal Kliment Voroshilov, he lifted the Siege of Leningrad in January 1944. Zhukov then led the Soviet offensive Operation Bagration (named after Pyotr Bagration, a famous Russian-Georgian general during the Napoleonic Wars), which some military historians believe was the greatest military operation of World War II. He launched the final assault on Germany in 1945, capturing Berlin (see Battle of Berlin) in April. Shortly before midnight, 8 May, German officials in Berlin signed an Instrument of Surrender, in his presence.

After the fall of Germany, Zhukov became the first commander of the Soviet occupation zone in Germany. As the most prominent Soviet military commander of the Great Patriotic War, he inspected the Victory Parade in Red Square in Moscow in 1945 while riding a white stallion. American General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander in the West, was a great admirer of Zhukov, and the two toured the Soviet Union together in the immediate aftermath of the victory over Germany.

Career after World War II

Immediately following the war Zhukov was the supreme Military Commander of the Soviet Occupation Zone in Germany, and became its Military Governor on June 10, 1945. A war hero and a leader hugely popular with the military, Zhukov constituted a most serious potential threat to Stalin's dictatorship. As a result, on April 10, 1946 he was replaced by Vasily Sokolovsky. After an unpleasant session of the Main Military Council, at which he was bitterly attacked and accused of being politically unreliable and hostile to the Party Central Committee, he was stripped of his position as Commander-in-Chief of the Ground Forces.[19] He was assigned to command the Odessa Military District, far away from Moscow and lacking strategic significance and attendant massive troops deployment, arriving there on 13 June 1946. He suffered a heart attack in January 1948, being hospitalised for a month. He was then given another secondary posting, command of the Urals Military District, in February 1948. After Stalin's death, however, Zhukov was returned to favour and became Deputy Defense Minister (1953).

In 1953 Zhukov was a member of the tribunal, headed by Konev, that arrested (and condemned to execution) Lavrenty Beria, who up until then was First Deputy Prime Minister and head of the MVD.[20] In 1955, when Bulganin became premier he appointed Zhukov as Defense Minister.[20]

Minister of Defense

As Soviet defence minister, Zhukov was responsible for the invasion of Hungary following the revolution in October, 1956. Along with the majority of members of the Presidium, he urged Nikita Khrushchev to send troops in support of the Hungarian authorities, and to secure the border with Austria. However, Zhukov and most of the Presidium were not eager to see a full-scale intervention in Hungary and Zhukov even recommended the withdrawal of Soviet troops when it seemed that they might have to take extreme measures to suppress the revolution. The mood on the Presidium changed again when Hungary's new Prime Minister, Imre Nagy, began to talk about Hungarian withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact, and the Soviet leadership pressed ahead ruthlessly to defeat the revolutionaries and install János Kádár in Nagy's place.

In 1957 Zhukov supported Khrushchev against his conservative enemies, the so-called "Anti-Party Group" led by Vyacheslav Molotov. Zhukov's speech to the plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist Party was the most powerful, directly denouncing the neo-Stalinists for their complicity in Stalin's crimes, though it also carried the threat of force: the very crime he was accusing the others of.

In June that year he was made a full member of the Presidium of the Central Committee. He had, however, significant political disagreements with Khrushchev in matters of army policy. Khruschev scaled down the conventional forces and the navy, while developing the strategic nuclear forces as a primary deterrent force, hence freeing up the manpower and the resources for the civilian economy.

Aboard the Chapayev class cruiser Kuibyshev, Zhukov visited Yugoslavia and Albania in October 1957, attempting to repair the Tito-Stalin split of 1948.[21] During the voyage, Kuibyshev encountered units of the United States Sixth Fleet, and passing honours were rendered.

Zhukov supported the interests of the military and disagreed with Khrushchev's policy. The same issue of Krasnaya Zvezda that announced Zhukov's return to Moscow also reported that Zhukov had been relieved of his duties.[22] Khrushchev, demonstrating the dominance of the Party over the army, had relieved Zhukov of his ministry and expelled him from the Central Committee. In his memoirs, Khrushchev claimed that he believed that Zhukov was planning a coup against him and that he accused Zhukov of this as grounds for expulsion at the Central Committee meeting.

In retirement

After Khrushchev was deposed in October 1964 the new leadership of Leonid Brezhnev and Aleksei Kosygin restored Zhukov to favour, though not to power. Brezhnev was said to be angered when, at a gathering to mark the twentieth anniversary of victory in the Great Patriotic War, Zhukov was accorded greater acclaim than himself. Brezhnev, a relatively junior political officer in the war, was always concerned to boost his own importance in the victory.

Zhukov remained a popular figure in the Soviet Union until his death in 1974 although by his own admission he was much better dealing with military matters than with politics. He was buried with full military honors.

Contemporary opinion

Zhukov is a unique example of a Soviet commander who was criticized for his tactics even inside the Soviet Union. This, of course, was directly related to his successes on the political scene in the Kremlin. When he was in favor, he was lauded as a great hero, "Georgy the Victory Bringer" (a pun: Saint George is also called the "Victory Bringer" in Russian). When he fell in disfavor, as with the other four-time-Hero of the Soviet Union Leonid Brezhnev, Zhukov was called a "cannibal marshal" (маршал-людоед). He remains the most controversial Soviet commander to this day, with diametrically opposed opinions published by his peers, military historians, and soldiers and commanders who served under him.

Zhukov's actual career is as diverse as those opinions. Brutal disregard for the lives of his soldiers often changes to the complete opposite. Zhukov spent more time than most Soviet commanders training his troops for battle, and preparing the battle plans, which often led to significantly lower casualty numbers compared to other Soviet commanders; for example at the Soviet counteroffensive during Battle of Moscow in the winter of 1941 Zhukov lost 139,586 men[23], or 13.6% of his total strength - while a comparable operation under General Kozlov lost about 40% of his men (estimates ranging between 150,000 and 175,000 killed) near Kerch[24]. As the war went on, Zhukov's casualties became even lower. At the Battle of Berlin Zhukov lost only 4.1% of his men, while Konev's forces, who faced weaker German opposition, lost 5%[25] and at the same time Rodion Malinovsky lost almost 8% at the Battle of Budapest.[26]

However Zhukov's desire to achieve success at any cost is undeniable. One of the most often quoted examples is Zhukov's actions during the defense of Istra Reservoir (Истринское водохранилище). General Rokossovsky, who commanded one of the Armies under Zhukov's command, requested to withdraw to more advantageous positions on November 18, 1941. Zhukov categorically refused. Rokossovsky then went for help over Zhukov's head, and spoke directly to Marshal Boris Shaposhnikov, Chief of the General Staff, and reviewing the situation Shaposhnikov immediately ordered a withdrawal. Zhukov reacted at once. He revoked the order of the superior officer, and ordered Rokossovsky to hold the position. In the immediate aftermath, Rokossovsky's army was annihilated and the Germans took hold of the strategically important Eastern bank.

Zhukov's proponents often explain his actions by the incredible pressure he was under. While pride was certainly a factor in many of Zhukov's decisions, he may well not have been as careless with the lives of his men had he not also been led by fear. Throughout the war Zhukov was put under more scrutiny than any other Soviet commander. The orders of his first major appointment, the defense of Moscow in 1941, were printed in all newspapers accompanied by a large portrait of Zhukov - something unprecedented until then. Stalin was making himself very clear: this was the man who'd be held responsible for the outcome. The precarious position occupied by Zhukov is easy to appreciate even for a modern reader. Zhukov's subsequent high-profile appointments left him equally little room for failure, and winning at all costs was not optional.

Zhukov's book of memoirs, Воспоминания и размышления (Remembrances and Contemplations), first published in 1969, has been used in both Russian and Western historiography. However, research using newly accessible sources has thoroughly discredited the book: for example, as Suvorov[27] points out, Zhukov numbers the German tanks allocated against the USSR in 1941 as 3712, and 4950 planes (p.263, p.411), and later suggests, that the number of enemy troops surpassed that of the Soviets "5 to 6 times, especially regarding tanks, artillery and aviation." (p.411) Obviously, this cannot be true. Zhukov's reports on pre-war military planning have also proved to be false, he recalled only one strategic game in January, 1941, whereas even later Soviet sources pointed out that two games were played.[28]

As archive sources testify, no operations necessary in case of enemy's assault on the USSR were actually played nor even discussed.[29] The first strategical game suggested Red Army counterstrike into East Prussian region, second game - strike into territories South of Polesye (Hungary, Romania). The latter one was favoured by the authorities (i.e Stalin), because the East Prussia/Warsaw region was heavily fortified and offensive there could have been more complicated. The second strategical game began in fact with Soviet counterstrike, from the depth of 90 to 180 km inside the enemy territory.[30] Therefore, taking into account the conclusion that "in January 1941 the operative-tactical branch of the leadership of the RKKA played on maps such a variant of warfare, which the actual West, i.e Germany, did not plan"[31], Zhukov's claim in his book as if he had rightly guessed the direction of German invasion is baseless. The actual Red Army main concentration south of Polesye has been used by many authors to support the thesis that Stalin was actually planning an assault on Germany.

Some historians consider Zhukov as a brilliant strategist, defining him as a man "whose brilliant military successes had earned him tremendous public admiration and popularity".[32] Indeed, many of his battles were examples of some of the most lopsided victories of the Second World War, ending with complete annihilation of his opponent (for instance Operation Uranus). Evidence exists that Zhukov did more to prepare himself and his troops for battle than most other Soviet commanders, thus giving them more of an edge in a fight. However once the battle began, Zhukov's focus was on nothing but victory. His brutality, while more publicized than most, was not at all uncommon. And many Russian historians continue to claim to this day that the outcome is all that matters. David Glantz has expressed the opinion, that "regrettably, today Zhukov is being criticised by some Russian historians for frequently resorting to massed frontal attacks".[33]

However, there is also evidence of dissimulation of his military defeats. For instance, the Battle of Rzhev, which can be considered as his biggest military defeat, was deemed secret and was not mentioned even in military literature till the 1970s. It is also important to note that Zhukov did not leave any theoretical works on military strategy or tactics. Therefore, several post-Soviet era historians no longer regard Zhukov as an outstanding strategist.[34]

In the popular belief and legends of the front-line soldiers, however, Zhukov is a fatherly figure who cares about his rank and file. He knows the day in and day out hardships of his troops, deeply loves Russia and all the soldiers that rose to its defense. In one anecdote, he dresses as a simple soldier and tries to get a hitch-hike to the front line from passing cars. Officers who did not stop their cars are later reprimanded for their lack of care toward the average "Ivan".

Controversies

On 28 September, 1941, Zhukov sent ciphered telegram No. 4976 to commanders of the Leningrad Front and Baltic Navy, announcing that families of soldiers captured by the Germans and returned prisoners would be shot.[35] This order was published for the first time in 1991 in the Russian magazine Начало (Beginning) No. 3. Also, in 1946, seven rail carriages with furniture which he was taking to Russia from Germany were impounded. In 1948, his apartments and house in Moscow were searched and many valuables looted in Germany were found [36].

In 1954, Zhukov was in command of a nuclear weapon test at Totskoye range, 130 miles (210 km) from Orenburg. A Soviet Tu-4 bomber dropped a 40 kiloton atomic weapon from 25,000 feet (7,600 m). He watched the blast from an underground nuclear bunker while about 5,000 Soviet military personnel staged a mock battle and about 40,000 troops were stationed about 8 miles (13 km) away from the epicentre. The number of soldiers killed, injured or made infertile as a result of the explosion is unknown because of the secrecy surrounding the event.

Awards

Zhukov was a recipient of numerous awards. In particular, he was four times Hero of the Soviet Union; besides him, only Leonid Brezhnev was a four-time hero. Zhukov was one of three double recipients of the Order of Victory. He was also awarded the Polish Virtuti Militari with the Grand Cross and Star and the Chief Commander grade of the American Legion of Merit, and was created a Knight Grand Cross of the Military Division of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath.[37] A partial listing is presented below.

Georgievskiy cross (Cross of St.George) 3rd and 4th classes (Russian Empire)

Soviet awards

Order of the Red Banner (3 times)

Marshal Star

Order of Lenin (6 times)

Gold Star of Hero of the Soviet Union (4 times)

Medal "Of XX of the years of RKKA"

Order of Suvorov 1st class (twice)

Medal "for the defense of Moscow"

Medal "for the defense of Leningrad"

Medal "for the defense of Stalingrad"

Medal "for the defense of the Caucasus"

Order of Victory (twice)

Medal "for the Liberation of Warsaw"

Medal "for the taking of Berlin"

Medal "for the victory over Germany in the Second World War 1941-1945 yr."

Medal " to the memory of the 800- anniversary of Moscow"

Medal "Of XXX of the years of the Soviet Army and Navy"

Medal "40 years of the Soviet Army and navy"

Medal "50 years Armed Forces of the USSR"

Medal "in memory of 250 years - the anniversary of Leningrad"

Medal "Of XX years of Victory in the Second World War 1941-1945"

Order of the October Revolution

Medal "100th Anniversary of Lenin's Birth"

Foreign awards

Order of Freedom, SFRY

Order of the Bath - Knight Grand Cross (Military Division), United Kingdom

Montgomery's Shield

Medal "25 years of the Bulgarian People's Army"

Medal "to the 90- anniversary of the birthday of Georgiy Dimitrov"

Partisan medal of Garibaldi (Italy)

Medal "Chinese- Soviet friendship"

"The star" of hero Mongolian Peoples Republic

Order of Sukhe-Bator (thrice)

Combat Order of the Red Banner MNR (twice)

Medal MNR to the memory of combat at the Khalkin-gol

Medal "50 years of the Mongolian People's Republic"

Medal "50 years of the Mongolian People's Army"

Medal of MNR "the 30- anniversary of victory at the Khalkin-gol"

Polonia Restituta, Poland, II and III class

Virtuti Militari, Poland Grand Cross

Medal "for Warsaw 1939-1945 yr." Poland

Medal "for Oder, Nisu and to Baltic Region", Poland

Chief Commander of the Legion of Merit

Grand Cross of the Legion d'Honneur

Military cross, France

Order of the White Lion 1st class, CSR

Order "for the Victory " of I st. CSR

Military cross, CSR

Memorials

The very first monument to Georgy Zhukov was erected in Mongolia, in memory of the Battle of Halhin Gol. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, this monument was one of the very few which did not suffer from the anti-Soviet backlash in the former Communist states.

A minor planet 2132 Zhukov discovered in 1975 by Soviet astronomer Lyudmila Chernykh is named in his honor.[38]

In 1995, commemorating Zhukov's 100th birthday, Russia adopted the Zhukov Order and the Zhukov Medal.

Recollections

Nobel laureate Joseph Brodsky's poem On the Death of Zhukov (Na smert’ Zhukova, 1974) is regarded by critics as one of the best poems on the war written by an author of the post-Second World War generation.[39] It is a clever stylisation of The Bullfinch, Derzhavin's elegy on the death of Generalissimo Suvorov in 1800. Brodsky obviously draws a parallel between the careers of these commanders.

Popular culture in Russia traditionally contends that Zhukov himself participated in Beria's arrest at the Kremlin - with one version having him exclaiming "in the name of the Soviet People, you are under arrest, you son of a bitch". Though psychologically gratifying to Russians in the post Stalin/Beria era, the historical accuracy of these accounts remain in doubt. Nikita Khrushchev's memoirs confirms this story, if not the use of colourful language.

In his book of recollections,[40] Zhukov was critical of the role Soviet leadership played during the war. The first edition of Vospominaniya i razmyshleniya was published during Brezhnev's reign, only on condition that criticism on Stalin was removed and Zhukov had to add an (invented) episode of a visit to Leonid Brezhnev, politruk at Southern Front, with the purpose of having consultations on military strategy.[41]

Footnotes

- ↑ Axell, Albert. Marshal Zhukov. Toronto: Pearson Education Ltd., 2003, ISBN 0-582-77233-8

- ↑ Chaney, Otto Preston. Zhukov. Revised ed. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996, ISBN 0-8061-2807-0

- ↑ (Russian)В огне революции и гражданской войны Lib.ru Retrieved on 2002, 07-17

- ↑ Soviet Prisoners of War: Forgotten Nazi Victims of World War II

- ↑ Russia's War: A History of the Soviet Effort: 1941-1945 ISBN 0-14-027169-4 by Richard Overy Page 91

- ↑ The Court of the Red Tsar by Simon Sebag Montefiore

- ↑ Суворов В. Тень победы. — М.:АСТ, 2002 http://militera.lib.ru/research/suvorov7/03.html

- ↑ (Russian)Соображения Генерального штаба Красной Армии по плану стратегического развертывания Вооруженных Сил Советского Союза на случай войны с Германией и ее союзниками Retrieved on 2002, 07-17

- ↑ Stalin's Missed Chance (Упущенный шанс Сталина) by Mikhail Meltyukhov http://militera.lib.ru/research/meltyukhov/10.html

- ↑ (Russian) I Take My Words Back (Беру Свои Слова Обратно) by Viktor Suvorov, ch. 9 http://militera.lib.ru/research/suvorov11/09.html

- ↑ Richard Overy, The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia, 2004, ISBN 0-393-02030-4

- ↑ Б.В. Соколов Правда о Великой Отечественной войне (Сборник статей). — СПб.: Алетейя, 1999

- ↑ Meltyukhov 2000:381, Военно-исторический журнал. 1991. № 12. С.20; 1941 год. Документы. Кн.1. С.185—187.

- ↑ "in exactly the same manner, on assertion by Meretskov, attack against Finland in 1939 was prepared as a "counterblow" within the framework of a plan for the cover of state border, although no-one, of course, assumed that Finland would have dared to attack the USSR first." -- Б.В. Соколов Правда о Великой Отечественной войне (Сборник статей). — СПб.: Алетейя, 1999

- ↑ as cited by Suvorov: http://militera.lib.ru/research/suvorov7/12.html

- ↑ Marshal G.K. Zhukov, Memoirs, Moscow, Olma-Press, 2002, p. 269

- ↑ P.Ya. Mezhiritzky (2002), Reading Marshal Zhukov, Philadelphia: Libas Consulting, chapter 32.

- ↑ Zhukov, p.353.

- ↑ William J. Spahr, 'Zhukov: The Rise and Fall of a Great Captain,' Presidio Press, 1993, pp.200-205

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Associated Press, 9 February 1955, reported in The Albuquerque Journal page 1 of that date.

- ↑ Spahr, 1993, p.235-8

- ↑ Krasnaya Zvezda, 27 October 1957, pp. 3,4, quoted in Spahr, 1993, p.238

- ↑ John Erickson, Barbarossa: The Axis and the Allies, Table 12.4

- ↑ K.A. Zalesskiy, Stalin's empire, Moscow, Veche, 2000.

- ↑ Anthony Beevor,Berlin the Downfall 1945

- ↑ Ungvary, Krisztian, The Siege of Budapest: One Hundred Days in World War II, Yale University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-300-10468-5

- ↑ Суворов В. Самоубийство: Зачем Гитлер напал на Советский Союз? — М.:АСТ, 2000

- ↑ "История советской военной мысли". "Наука", 1980

- ↑ Накануне войны. Материалы совещания высшего руководящего состава РККА 23-31 декабря 1940. M:1993. С.389

- ↑ Суворов В. Тень победы. — М.:АСТ, 2002

- ↑ Накануне войны. М., 1995. С.389

- ↑ Amy Knight, Beria, p.128, Princeton, 1995, ISBN 0-691-01093-5

- ↑ the Soviet Partisan Movement 1941-1945 by Leonid D. Grenkevich and D.Glantz

- ↑ Соколов Б.В. ‘’Неизвестный Жуков: портрет без ретуши в зеркале эпохи’’, ‘’1941-й год: война, которой не ждали’’. (Sokolov B.V. ‘’Unknown Zhukov’’, Chapter: ‘’1941: Uxpected War ’’) — Мн.: Родиола-плюс, 2000.

- ↑ (Russian)Sokolov, Boris.Георгий Жуков: народный маршал или маршал-людоед? Grain.ru Retrieved on 2002, 07-17

- ↑ Соколов Б.В. Неизвестный Жуков: портрет без ретуши в зеркале эпохи. (Unknown Zhukov by boris Sokolov) — Мн.: Родиола-плюс, 2000 — 608 с. («Мир в войнах»). ISBN 985-448-036-4.

- ↑ "British decoration for Russian Generals — the Tiergarten ceremony", Issue 50193, The Times (July 13, 1945), p. 4; col A.

- ↑ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. pp. 173. ISBN 3540002383. http://books.google.com/books?q=2132+Zhukov+TW3.

- ↑ Shlapentokh, Dmitry. The Russian boys and their last poet. The National Interest. 6/22/1996 Retrieved on 2002, 07-17

- ↑ Zhukov, Georgy. http://militera.lib.ru/memo/russian/zhukov1/10.html Жуков Г К. ‘’Воспоминания и размышления’’. В 2 т. — М.: Олма-Пресс, 2002.

- ↑ As pointed out by Mauno Koivisto in his book Venäjän idea, Helsinki. Tammi. 2001.

References

- (Russian) Zhukov, Georgy. Жуков Г К. ‘’Воспоминания и размышления’’. В 2 т. — М.: Олма-Пресс, 2002. Zhukov's memoirs online in Russian.

- Pavel N. Bobylev, Otechesvennaya istoriya, no. 1, 2000, pp. 41-64

Additional reading

- Spahr, William J. Zhukov: The Rise and Fall of a Great Captain. Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1993 (paperback, ISBN 0-89141-551-3).

- Suworow, Viktor. Marschall Schukow - Lebensweg über Leichen, Pour-le-Mérite, Selent, Germany, 2002, 350 pp.

External links

- Marshal Zhukov from the Voice of Russia website (in English)

- (Russian) Воспоминания и размышления The Memoirs of Georgy Zhukov

- (Russian) Zhukov's Awards

- (Russian) Shadow of Victory and Take Words Back, books by Viktor Suvorov, highly critical of Zhukov

- (Russian) Соколов Б.В. Неизвестный Жуков: портрет без ретуши в зеркале эпохи, Мн.: Родиола-плюс, 2000. (B.V.Sokolov. Unknown Zhukov)

- (Russian) Иосиф Бродский. На смерть Жукова (On the Death of Zhukov by Joseph Brodsky), 1974

- (Serbian) Georgy Zhukov

- Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Current Intelligence. Party–Military Relations in the USSR and the Fall of Marshal Zhukov, 8 June 1959.

| Preceded by Nikolai Bulganin |

Minister of Defence of Soviet Union 1955 1957 |

Succeeded by Rodion Malinovsky |

|

|||||