General Dynamics F-111

| F-111 Aardvark | |

|---|---|

|

|

| An F-111C of the Royal Australian Air Force with its wings unswept in 2006. | |

| Role | Fighter-bomber |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | General Dynamics |

| First flight | 21 December 1964 |

| Introduced | 18 July 1967 |

| Retired | 1998 (USAF) |

| Status | Active with RAAF |

| Primary users | United States Air Force Royal Australian Air Force |

| Number built | 554 |

| Unit cost | US$9.8 million (FB-111A)[1] |

| Variants | EF-111A Raven |

The General Dynamics F-111 is a medium-range interdictor and tactical strike aircraft that also fills the roles of strategic bomber, reconnaissance and electronic warfare in its various versions. Developed in the 1960s and first entering service in 1967, the United States Air Force (USAF) variants were officially retired by 1998. The only remaining operator of the F-111 is the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF).

The F-111 pioneered several technologies for production military aircraft, including variable geometry wings, afterburning turbofan engines, and terrain following radar for low-level, high-speed flight. Its design was highly influential, particularly for Soviet engineers, and some of its advanced features have since become commonplace. In its inception, however, the F-111 suffered a variety of development problems, and several of its intended roles, such as naval interception, failed to materialize.

In USAF service the F-111 has been effectively replaced by the F-15E Strike Eagle for medium-range precision strike missions, while the supersonic bomber role has been assumed by the B-1B Lancer. In 2007, the RAAF decided to replace its 21 F-111s in 2010 with 24 F/A-18F Super Hornets.[2][3]

Contents |

Development

The beginnings of the F-111 were in the TFX program, an ambitious early 1960s project to combine the United States Air Force requirement for a fighter-bomber to replace the F-105 Thunderchief with the United States Navy's need for a long-range carrier-based Fleet Air Defense fighter to replace the F-4 Phantom II. The fighter design philosophy of the day concentrated on very high speed, raw power, and air-to-air missiles.

Early requirements

The USAF's Tactical Air Command (TAC) was largely concerned with the fighter-bomber and deep strike/interdiction roles, which in the early 1960s still focused on the use of tactical nuclear weapons. The aircraft would be a follow-on to the F-105 Thunderchief, which was designed to deliver nuclear weapons low, fast and far. Air combat would be an afterthought until encountering MiGs over Vietnam in the mid-1960s. In June 1960 the USAF issued a specification for a long-range interdiction/strike aircraft able to penetrate Soviet air defenses at very low altitudes and very high speeds to deliver tactical nuclear weapons against crucial Soviet targets like airfields and supply depots. Included in the specification were a low-level speed of Mach 1.2, a high-altitude speed of Mach 2.5, a combat radius of 890 mi (1,430 km), good short-field performance, and a ferry range long enough to reach Europe without refueling.

Meanwhile the U.S. Navy had, since 1957, been searching for a long-range, high-endurance interceptor to defend its carrier battle groups against the new generation of Soviet jet bombers, which by then were being armed with large, long range anti-ship missiles. The Navy needed a Fleet Air Defense (FAD) aircraft with better loitering performance and load-carrying ability than the F-4 Phantom II, and one equipped with a powerful radar and a battery of long-range missiles to intercept both enemy bombers and their missiles.

The Navy had studied, but rejected, a subsonic, straight-winged missile carrier, the F6D Missileer. In December 1960, the Navy had been reconsidering variable geometry for the FAD requirement. The trend toward ever bigger, more powerful fighters posed a problem for the Navy: the current generation of naval fighters were already barely capable of landing on an aircraft carrier deck, and a still larger and faster fighter would pose even greater problems. An airframe optimized for high-speed — most obviously with a high-angle swept wing — is inefficient at cruising speeds, which reduces range, payload and endurance and leads to very high landing speeds. On the other hand, an airframe with a straight or modestly swept wing, while easier to handle and able to carry heavy loads over longer distances on a minimum of fuel, has lower ultimate performance. Variable geometry, which the Navy had tried and abandoned for the XF10F Jaguar in 1953, offered the possibility of combining both in a single airframe.

Tactical Fighter Experimental (TFX)

The Air Force and Navy requirements appeared to be different. However, on 14 February 1961 the new U.S. Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, formally directed that the services study the development of a single aircraft that would satisfy both requirements. Early studies indicated the best option was to base the Tactical Fighter Experimental (TFX) on the Air Force requirement and a modified version for the Navy.[4] In June 1961, Secretary McNamara ordered the go ahead on TFX despite Air Force and the Navy efforts to keep their programs separate.[5] The USAF and the Navy could only agree on swing-wing, two seat, twin engine design features. The USAF wanted a tandem seat aircraft for low level penetration, while the Navy wanted a shorter, high altitude interceptor with side by side seating.[4] Also, the USAF wanted the aircraft designed for 7.33 g with Mach 2.5 speed at altitude and Mach 1.2 speed at low level. The Navy had less strenuous requirements of 6 g with Mach 2 speed at altitude and high subsonic speed (approx. Mach 0.9) at low level.[4][6] So McNamara developed a basic set of requirements for TFX and ordered the Air Force on 1 September 1961 to develop it.[4]

A request for proposals (RFP) for the TFX was provided to industry in October 1961. In December of that year proposals were received from Boeing, General Dynamics, Lockheed, McDonnell, North American and Republic. The proposal evaluation group found all the proposals lacking but the best should be improved under study contracts. Boeing and General Dynamics were selected to enhance their designs. Boeing's proposal was recommended by the selection board in January 1962. However, the Boeing's engine was not considered acceptable. Switching to a crew capsule and alterations to radar and missile storage were also needed. The companies provided updated proposals in April 1962. Air Force reviewers favored Boeing's offering, but the Navy found both submissions unacceptable for its operations. Two more rounds of updates to the proposals were conducted with Boeing being picked by the selection board. Instead Secretary McNamara selected General Dynamics' proposal in November 1962 due to its greater commonality between Air Force and Navy TFX versions. The Boeing aircraft versions shared less than half of the major structural components. General Dynamics signed the TFX contract in December 1962. A Congressional investigation followed, but could not change the selection.[7]

The F-111A and B variants used the same airframe structural components and TF30-P-1 turbofan engines. They featured side by side crew seating in escape capsule as required by the Navy. The F-111B's nose was 8.5 feet (2.59 m) shorter due to its need to fit on existing carrier elevator decks, and had 3.5 feet (1.07 m) longer wingtips to to improve on-station endurance time. The Navy version would carry a AN/AWG-9 Pulse-Doppler radar and six AIM-54 Phoenix missiles. The Air Force version would carry the AN/APQ-113 attack radar and the AN/APQ-110 terrain-following radar and air-to-ground armament. Titanium was planned for most of the airframe. However, this proved to be too expensive and more conventional metals were used instead.[8]

With General Dynamics lacking experience with carrier-based fighters, it teamed with Grumman for the assembly and test the F-111B aircraft. In addition, Grumman would also build the F-111A's aft fuselage and the landing gear. The F-111A mock-up was inspected in September 1963. The first test F-111A was rolled out of the General Dynamics' Fort Worth, Texas plant on 15 October 1964. It was powered by YTF30-P-1 turbofans and used a set of ejector seats as the escape capsule not yet available.[8] The F-111A first flew on 21 December 1964 from Carswell AFB, Texas.[9] During early flight testing, the F-111A achieved a speed of Mach 1.3. The second F-111A first flew on February 25, 1965.[8]

Design

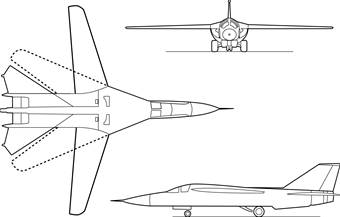

The F-111 is an all-weather attack aircraft capable of low-level penetration of enemy defenses to deliver ordnance on the target.[10] The F-111 features variable geometry wings, an internal weapons bay and a cockpit with side by side seating. The cockpit is part of an escape crew capsule.[11] The wing sweep varies between 16 degrees and 72.5 degrees (full forward to full sweep).[12]

Armament

Although conceived as a multi-role fighter, the F-111 became a long-range attack aircraft primarily armed with air-to-surface ordnance.

- Weapons bay

The F-111 has an internal weapons bay under the fuselage for various weapons.

- Cannon: All tactical combat versions (that is, not the EF-111A or FB-111A/F-111G) could carry a single M61 Vulcan 20 mm cannon with a very large (2,084 round) ammunition tank, covered by an eyelid shutter when not in use. Although carried by some USAF aircraft, the cannon was never actually used in combat, and was removed by the early 1980s; provision for the cannon has also been deleted from Australian F-111Cs.

- Bombs: The bay can alternately hold two conventional bombs, usually the Mk 117 type of nominal 750 lb/340 kg weight, although weapons up to the Mk 118 (3,000 lb/1,400 kg) were cleared.

- Nuclear weapons: All F-111 models except the EF-111A and the Australian F-111C were equipped to carry various free-fall nuclear weapons: tactical models generally carried the B43, B57, or B61. The FB-111A was a dedicated nuclear bomber for most of its life, and carried all of those weapons just mentioned, as well as the B83 and the AGM-69 Short Range Attack Missile. The FB-111A could carry one or two AGM-69 SRAM nuclear missiles in its weapons bay and up to four SRAMs on external wing pylons.

- Sensor pod: The F-111C and F-111F were equipped to carry the AN/AVQ-26 Pave Tack targeting system on a rotating carriage that kept the pod protected within the weapons bay when not in use. Pave Tack is a FLIR and laser rangefinder/designator that allows the F-111 to designate and drop laser-guided bombs.

- Reconnaissance pallet: Australian RF-111Cs carry a package of reconnaissance sensors and cameras for tactical recce missions. It contains two video cameras, a Honeywell AN/AAD-5 infrared linescan (recorded on video or film), a Fairchild KA-56E low-altitude and KA-93A4 high-altitude panoramic cameras, and a pair of CAI KS-87C split vertical cameras. It can also record photographs of the attack radar's display.

- Missiles: The F-111B was intended to be capable of carrying two AIM-54 Phoenix air-to-air missiles in the bay. General Dynamics proposed an arrangement that would allow two AIM-9 Sidewinders to be carried on a trapeze mounting in the bay (at the expense of the M61 cannon), along with a single (usually nuclear) bomb. This was not adopted, with the USAF and RAAF opting for the cannon instead. The AIM-7 Sparrow or AIM-4 Falcon, standard on the F-4 Phantom II, was never fitted, though later F-111 models had radars equipped to guide the Sparrow.

- Other equipment: Auxiliary fuel tanks and baggage pods were sometimes carried.

- External ordnance

The design of the F-111's fuselage prevents the carriage of external weapons under the fuselage (although there are two small stations, one on the weapon bay, the other on the rear fuselage between the engines, for ECM pods and/or datalink pods for guided weapons). All aircraft, except the FB-111A have provision for eight underwing pylons, four under each wing, with a capacity of 6,000 lb (2,700 kg) each. The inner pylons (3, 4, 5 and 6) pivot with the wing, but only one on each side can be loaded at maximum sweep. The outer pylons (1, 2, 7 and 8) are fixed, and can be loaded only if the wings are spread at less than 26°, causing drag at takeoff angle. The outermost pylons (1 and 8) have never been used operationally, and the second pair of fixed pylons (2 and 7) are fitted only rarely, for the carriage of fuel tanks. FB-111/F-111G models have provision to jettison their empty pylons in flight, reducing drag.

The limited number of fully swiveling pylons restricts the F-111's maximum practical weapons load, since the aircraft cannot use all pylons with the wings fully swept. By contrast, aircraft such as the F-14 and Tornado can carry their maximum bomb loads with fully swept wings.

The primary external armament of USAF tactical F-111s included:

- Free-fall GP bombs:

- Mk 82 (500 lb/227 kg)

- Mk 83 (1,000 lb/454 kg)

- Mk 84 (2,000 lb/907 kg)

- Mk 117 (750 lb/340 kg)

- Cluster bombs

- BLU-109 (2,000 lb/907 kg) hardened penetration bomb

- Paveway laser-guided bombs, including:

- GBU-10 (2,000 lb/907 kg)

- GBU-12 (500 lb/227 kg)

- GBU-28, a very specialized 4,800 lb (2,200 kg) penetration bomb

- BLU-107 Durandal runway-cratering bomb

- GBU-15 electro-optical bomb

- AGM-130 stand-off bomb, with a range of 40 miles (64 km).

Although all F-111s can carry laser-guided munitions, only those with Pave Tack (i.e., F-111F and Australian F-111C) are capable of self-designation. Others can drop laser-guided weapons only with the aid of another ground or air designator.

From the early 1980s onward, tactical F-111s were fitted with shoulder rails on the sides of the outboard swiveling pylon (designated stations 3A and 6A) for two AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles for self-defense. The standard Sidewinder fit was the AIM-9P, rather than the more modern AIM-9L or AIM-9M, whose larger fins were not compatible with the shoulder rail. The RAAF has considered replacing the Sidewinder with ASRAAM.

FB-111As could carry the same conventional ordnance as their tactical brothers, but their wing pylons were more commonly used for either fuel tanks or strategic nuclear gravity bombs. Until the weapon was withdrawn in 1990, they could carry up to four AGM-69 SRAM nuclear missiles on the wing pylons, although two was the more normal fit.

Australian F-111Cs have been equipped to launch the AGM-84 Harpoon anti-ship missile, AGM-88 HARM anti-radiation missile, and the AGM-142 Popeye stand-off missile.

Similar swing wing aircraft

The F-111 was the first production variable-geometry aircraft. The earlier subsonic Navy XF10F Jaguar had been cancelled in 1953. It inspired a number of aircraft throughout the 1960s, and even fictional aircraft on the Thunderbirds, but swing wings are extinct in newer designs due to higher cost, and the extra weight imposed by the swing wing mechanism. Nevertheless, several other types have followed, including the Soviet Sukhoi Su-17 "Fitter" (1966), Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-23 "Flogger" (1967), Tupolev Tu-22M "Backfire" (1969) and Tupolev Tu-160 "Blackjack" (1981), the U.S. F-14 Tomcat naval fighter (1970) and B-1 Lancer bomber (1974), and the European Panavia Tornado (1974). The Sukhoi Su-24 "Fencer" (1970), which resembles the F-111, also has side-by-side seating.

Operational history

United States

The first production F-111s were delivered on 18 July 1967 to the 428th, 429th and 430th Tactical Fighter Squadrons of the 474th Tactical Fighter Wing based at first out of Cannon AFB, New Mexico, which relocated in 1968 to Nellis AFB.

After early testing a detachment of six aircraft were sent in March 1968 to Southeast Asia for Combat Lancer testing in real combat conditions in Vietnam. In little over a month, three aircraft were lost and the combat tests were halted. It turned out that all three had been lost through malfunction (primarily with the terrain-following radar), not by enemy action. This caused a storm of political recrimination, with U.S. senators denouncing Secretary of Defense McNamara's judgment in procuring the aircraft. It was not until July 1971 that the 474 TFW was fully operational.

September 1972 saw the F-111 back in Southeast Asia, participating in the final month of Operation Linebacker and later the Operation Linebacker II aerial offensive against the North. F-111 missions did not require tankers or ECM support, and they could operate in weather that grounded most other aircraft. One F-111 could carry the bomb load of four F-4 Phantom IIs. The worth of the new aircraft was beginning to show, and over 4,000 combat F-111A missions were flown over Vietnam with only six combat losses.

In 1977, under Operation Creek Swing/Ready Switch the remaining F-111As were transferred from Nellis AFB, Nevada to the 366 TFW based at Mountain Home AFB, equipping the 389th, 390th, and 391st TFS. As the Ready Switch component of that operation, F-111Fs and their crews flew their aircraft to RAF Lakenheath, England to replace the F-4s and their crews of the 492nd, 493rd, and 494th Tactical Fighter Squadrons. As part of that operation, the F-4s from Lakenheath may have moved to Nellis AFB, Nevada.

On 14 April 1986, 18 F-111s and approximately 25 Navy aircraft executed Operation El Dorado Canyon by conducting air strikes against Libya. The 18 F-111s belonging to the 48th Tactical Fighter Wing flew what turned out to be the longest fighter combat mission in history.[13] The round-trip flight between RAF Lakenheath, United Kingdom and Libya of 6,400 miles (10,300 km) spanned 13 hours. One F-111 was shot down over Libya.[13]

In Desert Storm, F-111Fs completed 3.2 successful strike missions for every unsuccessful one, making it 47% more capable than the next leading strike aircraft.[14] The small 66-plane F-111F force was credited with 1,500 kills of Iraqi tanks and other mechanized vehicles. The F-111F was the only Desert Storm aircraft to deliver the GBU-15 and the 5,000-pound laser-guided, penetrating GBU-28.

The F-111 was in service with the USAF from 1967 through 1998. The Strategic Air Command had FB-111s in service from 1969 through 1990.

At a ceremony marking the F-111's USAF retirement, on 27 July 1996, it was officially named Aardvark, its long-standing unofficial nickname. Aardvark literally means "earth pig" in Dutch/Afrikaans, consequently, in Australia, the F-111 is often known by the affectionate nickname "Pig". The USAF retired the EF-111 variant in 1998.

Australia

The Australian government ordered 24 F-111C aircraft in 1963 to replace the RAAF's English Electric Canberra in the bombing and tactical strike role. While the first aircraft was officially handed over in 1968, structural integrity problems found in the USAF fleet delayed the service entry of the F-111C until 1973, USAF F-4 Phantom IIs being leased as an interim measure. Four aircraft were modified to RF-111C reconnaissance configuration, retaining their strike capability. Australia selected the F-111 ostensibly as the delivery platform for planned strategic nuclear weapons. This role was negated when Australia ratified the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons in 1973.

Since their introduction Australia's F-111s have been operated by No. 1 Squadron RAAF in the strike role with No. 6 Squadron RAAF operating the aircraft as an operational conversion unit. A temporary flight designated the Washington Flying Unit ferried Australia's first 12 aircraft from the United States in 1973 and F-111s have been loaned to the RAAF's Aircraft Research and Development Unit.

The Royal Australian Air Force's F-111 fleet has at times been controversial. Controversies surrounding the F-111 include:

- The long delay to the delivery of the aircraft was a significant political issue in the late 1960s and early 1970s. This occurred around the same time that massive delays and cost blowouts to the Sydney Opera House were making headlines, prompting some commentators to dub the F-111 the "Flying Opera House".[15]

- Their use by the Hawke federal government to take surveillance photos of the Franklin Dam project in Tasmania. The use of an RAAF aircraft to "spy" on its own territory led to the minister responsible, Senator Gareth Evans earning the nickname "Biggles" (after the famous pilot-hero of a number of books by Captain W.E. Johns).[16][17]

- Poor work conditions for F-111 ground crew involved in sealing/de-sealing F-111 fuel tanks resulted in permanent brain damage to a number of ground crew before conditions were improved.

A number of ex-USAF aircraft have been delivered to Australia, as attrition replacements and to enlarge the fleet. Four aircraft modified to F-111C status were delivered in 1982, while 18 F-111G aircraft were purchased in 1992 and delivered in 1994. Additional stored USAF airframes are reserved as a spares source.

In Australian military and aviation circles, the F-111 Aardvark is affectionately known as the "Pig", due to its Terrain Following ability, unique at the time of its introduction, that gives it the ability to "hunt amongst the weeds". Another, less generous explanation of the source of the nickname refers to the colloquialism "Pigs Might Fly". A third origin can be posited from the word aardvark, which translates into English as "Earth Pig".

While the F-111 has not seen combat in Australian service, it is known that F-111 aircraft were placed on high alert during the initial phase of the Australian-lead intervention (INTERFET) into East Timor in 1999. During the first Gulf War in 1991, the United States Government asked Australia to deploy RF-111 aircraft to the Persian Gulf. This request was denied as the Australian government judged that these aircraft were too important to Australia's security to risk in a distant war.

In 2006, four F-111s based at RAAF Amberley were used to sink the North Korean freighter Pong Su in Jervis Bay in joint RAAF and RAN military exercise.

In 2007 Australia decided to retire its F-111s in 2010 and signed a contract to acquire 24 F/A-18Fs as an interim replacement.[2] In March 2008 after a review, the new Labor government confirmed its purchase of the Super Hornets.[3] The drawdown of the RAAF's F-111 fleet has begun with the retirement of the F-111G models operated by No. 6 Squadron RAAF in late 2007. No. 1 and No. 6 Squadrons being reequipped with F/A-18Fs.

Variants

F-111A

The F-111A was the initial production version of the F-111. It had TF30-P-3 engines with 12,000 lbf (53 kN) dry and 18,500 lbf (82 kN) afterburning thrust and "Triple Plow I" variable intakes, providing a maximum speed of Mach 2.2 (1,450 mph / 2,300 km/h) at altitude.

The -A's Mark I avionics suite included the General Electric AN/APQ-113 attack radar mated to a separate Texas Instruments AN/APQ-110 terrain-following radar under the nose and a Litton AJQ-20 inertial navigation and nav/attack system.

Total production of the F-111A was 158, including 17 preproduction aircraft that were later brought up to production standards. In 1982, four surviving F-111As were converted to F-111C standard and provided to Australia as attrition replacements. They were fitted with the longer-span wings and reinforced landing gear of the -C, and subsequently were almost indistinguishable from new-build F-111Cs. Some of the -As delivered to the RAAF were Vietnam veterans, purportedly still bearing the scars of anti-aircraft fire.

A total of 42 F-111As were converted to EF-111A Ravens for an electronic warfare tactical electronic jamming role.

Three pre-production aircraft were provided to NASA for various testing duties. One was fitted with a variable-camber wing as part of the Advanced Fighter Technology Integration program in the 1980s; it was retired to the United States Air Force Museum at Wright Patterson AFB in 1989.

Most of the unconverted surviving F-111As were retired in 1991 and mothballed at AMARC, Davis Monthan AFB.

F-111B

The F-111B was to be a fleet air defense (FAD) fighter for the U.S. Navy, fulfilling a long-standing naval requirement for a fighter capable of carrying heavy, long-range missiles to defend carriers and their battle groups from Soviet bombers and fighter-bombers equipped with anti-ship missiles. The Navy had just cancelled the F6D Missileer, a concept for a slow, straight-winged jet with the advanced Hughes AN/AWG-9 pulse-Doppler radar, which could detect low flying targets among ground clutter, and lift eight new AIM-54 Phoenix long range, air-to-air missiles, which could attack multiple aircraft simultaneously at ranges out to 100 miles (160 km). The concept was soon cancelled, but the F-111 offered a platform with the range, payload, and Mach 2 performance of a fighter to intercept targets quickly, but with swing wings and turbofan engines, it could also loiter on station for long periods. The F-111B would carry six Phoenix missiles, but have no gun or other short range armament. General Dynamics, having no experience with carrier-based aviation, partnered with Grumman for this version.

The F-111B was a compromise that attempted to reconcile the Navy's very different needs with an aircraft whose basic configuration was largely set by the USAF need for a supersonic strike aircraft. These compromises would harm both USAF and USN versions. The side-by-side seating was preferred by the Navy from the Missileer. The F-111B was shorter than the F-111A, in order to enable it to fit on aircraft carrier deck edge elevators between the flight deck and the hangar deck. The F-111B also had a longer wingspan than its USAF counterpart (70 ft/21.3 m compared to 63 ft/19.2 m) for increased range and cruising endurance. Although the Navy had wanted a 48-inch (122 cm) radar dish for long range, they were forced to accept a 36-inch (91.4 cm) dish for compatibility. The Navy had requested a maximum takeoff weight of 50,000 lb (22,686 kg), but then-Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara forced the Navy to compromise at 55,000 lb (24,955 kg). This weight goal proved to be overly optimistic.

Excessive weight plagued the F-111B throughout its development. Not only were prototypes far over the 55,000 lb (24,955 kg) limit, efforts to redesign the airframe only made matters worse. The excessive weight made the aircraft seriously underpowered. In landing configuration at carrier weights, the F-111B could not maintain level flight on one engine, which would be a major problem once committed to the approach. Worse, its visibility for carrier approach and landing were abysmal.

Requirements for the F-111B had been formulated before air combat over Vietnam in 1965 showed the Navy still had a need for an aircraft which could engage MiG fighters at close range. The Navy desired a fighter with more performance than the F-4 Phantom II, yet in trials, the maneuverability and performance of the F-111B, especially in the crucial medium-altitude regimen, was decidedly inferior to the Phantom. During the congressional hearings for the aircraft, Vice Admiral Thomas F. Connolly, then Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Air Warfare, famously responded to a question from Senator John C. Stennis as to whether a more powerful engine would cure the aircraft's woes with "There isn't enough power in all Christendom to make that airplane what we want!"[18]

By October 1967, the Navy was finally convinced that the F-111B program was a lost cause and recommended its cancellation, which occurred in 1968 after seven had been delivered,[19] two of which had crashed. The swing-wing configuration, TF-30 engines, Phoenix missiles and radar developed for this aircraft (and the earlier, canceled F6D Missileer) were used on its replacement, the F-14 Tomcat, also designed by Grumman. The Tomcat would be large enough to carry the AWG-9 and Phoenix weapons system while exceeding the agility and speed of the F-4 Phantom.

F-111C

The F-111C was an export version for Australia, combining F-111A/E avionics with the long-span wings and heavier landing gear originally designed for the F-111B. Twenty-four were originally ordered in 1963, although development delays and structural problems kept them from entering service until 1973.

Four aircraft were modified to RF-111C reconnaissance configuration, retaining their strike capability. The RF-111C carries a reconnaissance pack with four cameras and an infrared linescan unit.

F-111C aircraft have been equipped to carry Pave Tack FLIR/laser pods, and later underwent an extensive Avionics Upgrade Program, with AN/APQ-169 attack radar replacing the elderly AN/APQ-113, Texas Instruments AN/APQ-171 terrain-following radar, twin Honeywell H423 ring-laser gyro INS, GPS receiver, modern digital databus, mission computer, and stores-management system, and cockpit multi-function displays (MFDs). Their engines were updated to TF30-P-108/109RA standard, with 21,000 lbf (93 kN) thrust. Four ex-USAF F-111As were refitted to F-111C standard and delivered to Australia as attrition replacements.

In late 2001, wing fatigue problems were discovered with one of the F-111C fleet. As a result a decision was made in May 2002 to replace the wings with spares taken from ex-USAF F-111Fs stored at the Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Center. The short span wings underwent a refurbishment in Australia which included extending the span in effect making the wings the same as the F-111C and F-111G models.[20]

F-111D

The F-111D was an upgraded F-111A equipped with newer Mark II avionics, more powerful engines, improved intake geometry, and an early glass cockpit. First ordered in 1967, extensive development problems delayed service entry until 1974, and only 96 were built.

The F-111D used the new Triple Plow 2 intakes, which were located four inches (100 mm) further away from the airframe to prevent engine ingestion of the sluggish boundary layer air that was known to cause stalls in the TF30 turbofans. It had more powerful TF30-P-3 engines with 12,000 lbf (53 kN) dry and 18,500 lbf (82 kN) afterburning thrust.

More significant and problematic were the Mark II avionics. These were digitally integrated microprocessor systems, some of the first used by the USAF, offering tremendous capability, but substantial problems during introduction. The main radar was the General Electric AN/APQ-114, with Doppler beam-sharpening, moving target indicator (MTI), and continuous wave mode for guiding semi-active radar homing missiles (which the standard AN/APQ-113 set lacked). This was matched with an Autonetics inertial navigation/attack radar system, Marconi Doppler radar for navigation, a horizontal situation display, an IBM processor, and a Norden integrated systems display, with modern multi-function displays (MFDs). These last proved to be a major source of trouble, serving to multiply the development problems experienced with the individual systems. Considerable acrimony between the contractors resulted, and it took years before the problems were solved. F-111 crews considered the -D the most capable (and user-friendly) version of the aircraft when everything functioned, but that was rare before the 1980s.

Incidentally, the F-111D was never equipped to carry what proved to be the "Aardvark's" most useful sensor system, the AN/AVQ-26 Pave Tack pod.

The F-111D was withdrawn from service in 1992 for mothballing at AMARC.

F-111E

The F-111E was a simplified, interim model ordered after the prolonged teething troubles of the F-111D. It used the -D's Triple Plow 2 intakes and more powerful TF30-P-3 engines, but retained the -A's Mark I avionics.

Although conceived after the -D, the F-111E was actually delivered before it. The first flight of an -E was 20 August 1969. A total of 94 were built.

Some F-111Es were based with the 20th Fighter Wing at RAF Upper Heyford in Oxfordshire (United Kingdom) until 1993, and the type saw service in Operation Desert Storm. All F-111Es were withdrawn to storage in 1993 and 1994.

F-111F

The F-111F was the final F-111 variant produced for Tactical Air Command, with more modern and advanced Mark IIB avionics that were more capable than the F-111E and much more reliable than the F-111D. A total of 106 were produced between 1971 and 1976. The aircraft were initially assigned to the 366 TFW at Mountain Home AFB, Idaho. In 1977, the F-111Fs were reassigned to the 48 TFW based at RAF Lakenheath in the United Kingdom, with some assigned to the 57th Fighter Weapons Wing at Nellis AFB.

The F-111F's Mark IIB avionics suite used a simplified version of the FB-111A's radar, the AN/APQ-144, lacking some of the strategic bomber's operating modes but adding a new 2.5 mi (4.0 km) display ring. Although it was tested with digital moving-target indicator (MTI) capacity, it was not used in production sets. It used Texas Instruments AN/APQ-146 terrain-following radar, Litton inertial navigation, and the F-111E's Weapon Control Panel. The internal weapons bay was normally occupied by an AVQ-26 Pave Tack FLIR and laser designator system for the delivery of precision laser-guided munitions. The radar was subsequently upgraded to AN/APQ-161, with the AN/APQ-171 terrain-following set. The later Pacer Strike avionics update program added new digital electronics and databus.

The -F also used the Triple Plow 2 intakes, along with the substantially more powerful TF30-100 turbofan with 25,100 lbf (112 kN) afterburning thrust. This substantially improves the -F's performance, allowing a top speed of Mach 2.5 at altitude and enabling an unloaded F-111F to supercruise (fly at supersonic speeds without afterburner). In 1985-86, engines were upgraded to the TF30-P-111 turbofan.

The F-111F made its combat debut in Operation El Dorado Canyon against Libya in 1986, and was used in Operation Desert Storm against Iraq in an anti-armor ("tank-plinking") role.

Various plans to upgrade the F-111F, including the adoption of the General Electric F110 engine (used in the F-14D Tomcat), were proposed, but not implemented because they might have interfered with the USAF's political efforts to build the F-22 Raptor. As a result, the last USAF F-111s were withdrawn from service on 27 July 1996, replaced by the F-15E Strike Eagle.

FB-111A/F-111G

The FB-111A was a strategic bomber version of the F-111 developed as an interim aircraft for the Strategic Air Command to replace the elegant but troublesome supersonic B-58 Hustler and early models of the B-52 Stratofortress. The planned replacement program, the Advanced Manned Strategic Aircraft, was proceeding slowly, and the Air Force was concerned that fatigue failures in the B-52 fleet would leave the strategic bomber fleet dangerously under strength. Although 263 airframes were planned originally, the total was finally cut to just 76. The first production aircraft was delivered in 1968. The FB-111A never had an official popular name, but it was commonly called the "Switchblade."

The FB-111A was 2 ft 1.5 in (650 mm) longer than the F-111A, allowing carriage of about 585 gallons (2,214 L) extra fuel, and was fitted with the longer wings of the abortive F-111B and F-111K for greater range and load-carrying ability. A stronger undercarriage and landing gear compensated for the higher take-off weights (gross weight rose to 119,250 lb/54,105 kg). All but the first aircraft had the Triple Plow 2 intakes and the TF30-P-7 with 12,500 lbf (56 kN) dry and 20,350 lbf (90 kN) afterburning thrust.

The FB-111A had new electronics, known as the SAC Mk IIB suite. The Mk IIB retained the F-111A's Texas Instruments AN/ANPQ-134 terrain-following radar and Honeywell AN/APN-167 radar altimeter. Radar was the General Electric AN/APQ-114, with a new north-oriented display, a beacon tracking mode, and a photo recording mode. To those components, the FB-111A added a Rockwell AN/AJN-16 inertial navigation system, Singer-Kearfott AN/APN-185 Doppler radar, and the Litton AN/ASQ-119 Astrotracker astrocompass, which allowed navigation by stellar positioning (a similar system had been used on the SR-71 Blackbird). A Horizontal Situation Display was added along with the AN/AYK-6 cockpit display. A unique feature of the FB-111A was that the TFR was integrated into the automatic flight control system, allowing "hands-off" flight at high speeds and low levels (down to 200 feet), even in adverse weather.

Armament for the strategic bombing role was the Boeing AGM-69 SRAM (short-range attack missile) which had Mach 3 speed and 110-mile (180 km) range. Two could be carried in the internal weapons bay and four more on the inner underwing pylons. Nuclear gravity bombs were also typical FB armament. Fuel tanks were often carried on the third non-swivelling pylon of each wing. Promotional photos showed a conventional bombload to a theoretical total of 50, 750 lb (340 kg) M117 weapons on eight pylons and bomb bay, but it was never used in a conventional role. In 1990, the SRAM was withdrawn from service amid concerns about the integrity of its nuclear warhead in the case of fire, and subsequently only unpowered bombs were available.

Multiple advanced FB-111 strategic bomber designs were proposed by General Dynamics in the 1970s. The first design, referred to as "F-111G" by the company, was a larger aircraft with more powerful engines with more payload and range. The next was a lengthened "FB-111H". It featured more powerful General Electric F101 turbofan engines, a 12 ft 8.5 in longer fuselage and redesigned, fixed intakes. The rear landing gear were moved outward so armament could be carried on the fuselage there. The FB-111H (also referred as FB-111B/C) was offered as an alternative to the B-1A.[21]

The FB-111 became surplus to SAC's needs after the introduction of the Rockwell B-1B Lancer. With the disestablishment of SAC in 1992 and movement of all former SAC bomber aircraft to the newly established Air Combat Command (ACC), the remaining FB-111s were retired from Plattsburgh AFB, NY and Pease AFB, NH and subsequently converted to a tactical configuration renamed the F-111G. They were used primarily for training.

The F-111G did undergo an avionics upgrade program that added a digital computer, dual AN/ASN-41 ring-laser gyro INS, AN/APN-218 Doppler navigation, and an updated terrain-following radar. The astrocompass system was deleted. The G model did not remain in USAF service for long, being mothballed in 1993, but 15 were bought by Australia to supplement its F-111Cs.

F-111K

The British government cancelled the BAC TSR-2 in 1965, citing the lower costs of the TFX and ordered 50 F-111K aircraft in 1967. The F-111K was based on the F-111A, modified for British equipment and weapons. This included weapons bay changes, compatibility with the Martel anti-shipping missile, the addition of a retractable refuelling probe and the use of FB-111A landing gear for a higher gross take off weight. Prototypes of both the strike and TF-111K trainer aircraft were started and were in the final stages of build when the order was cancelled just over a year later. Updated estimates of performance indicated that range and speed at altitude would be worse than expected and fall short of the specification. Cost increase together with devaluation of the pound meant that the cost would be around £3 million each and this was the reason cited for cancellation.[22] As a substitute, Blackburn Buccaneers and F-4 Phantom IIs were purchased instead for the RAF. These would eventually be replaced by the Panavia Tornado which also employs swing-wings like the F-111.

EF-111A Raven

To replace the elderly and obsolescent Douglas EB-66, in 1972 the USAF contracted Grumman to convert 42 existing F-111As into electronic warfare/ECM aircraft. They can be distinguished from other A-models by the equipment bulge atop their tails, a feature leading to the nickname "Fat Tail". In May 1998, the USAF withdrew the final EF-111As from service, placing them in storage at AMARC. In the short term, EA-6B Prowlers are fulfilling this function for both the U.S. Navy and USAF.

Aircraft on display

- F-111A

- 63-9766 - Air Force Flight Test Center Museum, Edwards AFB, CA (first F-111)

- 63-9767 - Octave Chanute Aerospace Museum (former Chanute AFB), IL

- 63-9768 - used as a ground trainer, RAAF Amberley, Australia

- 63-9771 - Cannon AFB, Clovis, NM

- 63-9773 - Sheppard AFB Air Park, Sheppard AFB, TX

- 63-9775 - United States Space & Rocket Center, Huntsville, AL

- 63-9776 - Mountain Home AFB, ID (only RF-111A, marked as 66-0022)

- 63-9778 - Air Force Flight Test Center Museum, Edwards AFB, CA (TACT/AFTI F-111)

- 63-9782 - former Griffiss AFB, NY

- 66-0012 - American Airpower Museum, Long Island, NY

- 67-0046 - Brownwood Regional Airport, Brownwood, TX

- 67-0047 - Sheppard AFB Air Park, Sheppard AFB, TX

- 67-0051 - Historic Aviation Memorial Museum, Tyler Pounds Regional Airport, TX (marked as 67-0050)

- 67-0057 - Dyess Air Force Base Linear Air Park, Abilene, TX

- 67-0058 - Mountain Home AFB, ID

- 67-0067 - National Museum of the United States Air Force, Wright-Patterson AFB, OH

- 67-0069 - Southern Museum of Flight, Birmingham, AL

- 67-0100 - Nellis AFB, Nevada (gate guard)

- F-111B

- 151972 - Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, CA (possibly scrapped)

- 152715 - Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, CA (last complete F-111B)

- EF-111A

- 66-0016 - Cannon AFB, Clovis, NM

- 66-0047 - In a scrapyard in the Mojave Desert near the airport

- 66-0049 - Mountain Home AFB, ID (first EF-111A prototype)

- 66-0057 - National Museum of the United States Air Force, Wright-Patterson AFB, OH

- F-111D

- 68-0092 - Yanks Air Museum, Chino, CA

- 68-0125 - Combat Air Museum, Topeka, Kansas

- 68-0140 - Cannon AFB, Clovis, NM (F-111 'Vark' Memorial Park)

- F-111E

- 67-0120 - American Air Museum, Imperial War Museum Duxford, RAF Duxford. UK

- 68-0009 - Undergoing restoration by the OV-10 Bronco Association, TX

- 68-0011 - RAF Lakenheath, UK (gate guard, marked as 48th TFW F-111F)

- 68-0020 - Hill Aerospace Museum, Hill AFB, UT (nicknamed "My Lucky Blonde")

- 68-0027 - Confederate Air Force, Midland/Odessa, TX

- 68-0033 - Pima Air & Space Museum, Tucson, AZ

- 68-0055 - Museum of Aviation, Robins AFB, GA (nicknamed "Heartbreaker")

- 68-0058 - Air Force Armament Museum, Eglin AFB, FL

- FB-111A

- 67-0159 - Aerospace Museum of California (FB-111A development aircraft)

- 68-0239 - former K.I. Sawyer AFB, MI (nicknamed "Rough Night")

- 68-0245 - March Field Air Museum, March ARB, Riverside, CA (nicknamed "Ready Teddy")

- 68-0248 - South Dakota Air and Space Museum, Ellsworth AFB, SD (nicknamed "Free For All")

- 68-0259 - set aside for parts, RAAF Amberley, Australia

- 68-0267 - Strategic Air and Space Museum (adjacent to Offutt AFB), Ashland, NE (nicknamed "Black Widow")

- 68-0275 - Kelly Field Heritage Museum, Lackland AFB / Kelly Field (former Kelly AFB), TX (painted in tactical scheme)

- 68-0284 - Eighth Air Force Museum, Barksdale AFB, LA

- 68-0286 - Clyde Lewis Airpark (adjacent to former Plattsburgh AFB), Plattsburgh, NY (nicknamed "SAC Time")

- 68-0287 - Wings Over the Rockies Air and Space Museum, former Lowry AFB, Denver, Colorado[23]

- 69-6507 - Castle Air Museum, former Castle AFB, Atwater, CA (nicknamed "Madam Queen")

- 69-6509 - Whiteman AFB, MO (gate guard) (nicknamed "The Spirit of the Seacoast")

- F-111F

- 70-2364 - In the median of US70, south of Portales, NM

- 70-2390 - National Museum of the United States Air Force, Wright-Patterson AFB, OH

- 70-2408 - Santa Fe Airport, NM

- 74-0177 - National Cold War Exhibition, Royal Air Force Museum, Cosford, UK

(F-111C aircraft that are still in service with the Royal Australian Air Force are not listed above).

Specifications (F-111F)

Data from Quest for Performance[24]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2 (pilot and weapons system operator)

- Length: 73.5 ft (22.4 m)

- Wingspan:

- Spread: 63 ft 0 in (19.2 m)

- Swept: 32 ft 0 in (9.8 m) (9.75 m)

- Height: 17.13 ft (5.22 m)

- Wing area:

- Spread: 657.4 ft² (61.07 m²)

- Swept: 525 ft² (48.77 m²)

- Airfoil: NACA 64-210.68 root, NACA 64-209.80 tip

- Empty weight: 47,481 lb (21,537 kg)

- Loaded weight: 82,843 lb (37,577 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 98,979 lb (44,896 kg)

- Powerplant: 2× Pratt & Whitney TF30-P-100 turbofans

- Dry thrust: 17,900 lbf (79.6 kN) each

- Thrust with afterburner: 25,100 lbf (112 kN) each

- Zero-lift drag coefficient: 0.0186

- Drag area: 9.36 ft² (0.87 m²)

- Aspect ratio: spread: 7.56, swept: 1.95

Performance

- Maximum speed: Mach 2.5 (1,650 mph, 2,655 km/h)

- Combat radius: 1,330 mi (1,160 NM, 2,140 km)

- Ferry range: 3,220 mi (2,800 NM, 5,190 km)

- Service ceiling 56,650 ft (17,270 m)

- Rate of climb: 25,890 ft/min (131.5 m/s)

- Wing loading:

- Spread: 126.0 lb/ft² (615.2 kg/m²)

- Swept: 158 lb/ft² (771 kg/m²)

- Thrust/weight: 0.61

- Lift-to-drag ratio: 15.8

Armament

- Guns: 1× M61 Vulcan 20 mm (0.787 in) gatling cannon (seldom fitted)

- Hardpoints: external hardpoints have a capability of 31,500 lb (14,300 kg) of ordnance

Popular culture

American artist James Rosenquist immortalized the aircraft in his acclaimed 1965 room-sized pop art painting entitled F-111 that features an early natural-finish example of the aircraft in USAF markings. The painting hangs in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

The Australian band Cold Chisel recorded a song called "F-111".[25] British pop-cyberpunk band Sigue Sigue Sputnik had a world hit in 1986 with the song "Love Missile F1-11". F-111 Records was an electronic music imprint within Warner Bros. Records that ran from 1995–2001.

The F-111 is also the featured aircraft in the novel Chains of Command by former F-111 crew member Dale Brown.

See also

Related development

- EF-111A Raven

Comparable aircraft

- F-14 Tomcat

- BAC TSR-2

- Sukhoi Su-24

- Panavia Tornado

- Sukhoi Su-34

Related lists

- List of bomber aircraft

- List of military aircraft of the United States

References

Notes

- ↑ Knaack, Marcelle Size. Encyclopedia of US Air Force Aircraft and Missile Systems: Volume 1 Post-World War II Fighters 1945-1973. Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History, 1978. ISBN 0-912799-59-5.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Super Hornet Acquisition Contract Signed

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 ALP to stick with Super Hornet buy - National - theage.com.au

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Gunston 1978, pp. 8-17.

- ↑ Eden 2004, pp. 196-197.

- ↑ Miller 1982, pp. 11-15.

- ↑ Gunston 1978, pp. 18-20.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "General Dynamics F-111A", Joe Baugher's site, December 23, 1999.

- ↑ Eden 2004, p. 197.

- ↑ General Dynamics F-111D to F Aardvark, US Air Force National Museum.

- ↑ Eden 2004, pp. 196-201.

- ↑ F-111 design, globalsecurity.org

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Boyne, Walter J. "El Dorado Canyon", Air Force Magazine, March 1999.

- ↑ Archive

- ↑ F-111

- ↑ Stateline Tasmania, ABC 27 June 2003

- ↑ Papers on Parliament 1989 "In preparing the Commonwealth's case for the inevitable High Court challenge by Tasmania, Evans earned the popular title of 'Biggles' for arranging to have Royal Australian Air Force planes fly 'spy flights' over the dam site to collect court evidence." (p27)

- ↑ "Tests & Testimony", Time magazine, March 22, 1968.

- ↑ General Dynamics/Grumman F-111B, J Baugher, November 7, 2004.

- ↑ Pittaway, Nigel. "21st century Pigs: F-111 in RAAF Service." International Air Power Review, Vol. 6, 2002, p. 18-31.

- ↑ Miller 1982, pp. 59-62, 73-77.

- ↑ Buttler, Tony. British Secret Projects: Jet Bombers Since 1949. London: Midland Publishing, 2003. ISBN 1-85780-130-X.

- ↑ Wings Over the Rockies Air & Space Museum - FB-111A Denver, CO

- ↑ Loftin, LK, Jr. Quest for performance: The evolution of modern aircraft. NASA SP-468, NASA, 6 August 2004. Retrieved 22 April 2006.

- ↑ Song lyrics

Bibliography

- Eden, Paul. "General Dynamics F-111 Aardvark/EF-111 Raven." Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft. Amber Books, 2004. ISBN 1904687849.

- Gunston, Bill. F-111. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1978. ISBN 0-684-15753-5.

- Miller, Jay. General Dynamics F-111 "Arardvark". Aero Publishers, 1982. ISBN 0-8168-0606-3.

- Thornborough, Anthony M. F-111 Aardvark. London: Arms and Armour, 1989. ISBN 0-85368-935-0.

- Winchester, Jim, ed. "General Dynamics FB-111A." "Grumman/General Dynamics EF-111A Raven." Military Aircraft of the Cold War (The Aviation Factfile). London: Grange Books plc, 2006. ISBN 1-84013-929-3.

External links

- Royal Australian Air Force F-111 page

- F-111.net

- F-111 on ausairpower.net

- F-111 page on GlobalSecurity.org

- F-111 profile on Aerospaceweb.org

- F-111 page on USAF National Museum web site

- Are the F-111's Really Stuffed? by Don Middleton ADA Defender Summer 2006/07

- Report of the RAAF Evaluation Team for a replacement Strike/Reconnaissance Aircraft for Air Staff Requirement (ASR) 36 on the National Archives of Australia site

- Aviation Enthusiast's List of F-111 Survivors

- Escape Capsule for F-111D Serial #68-0125 on display at Combat Air Museum

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||