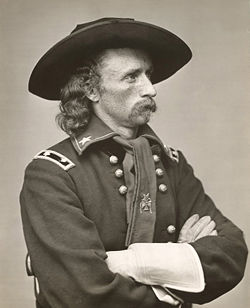

George Armstrong Custer

| George Armstrong Custer | |

|---|---|

| December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876 (aged 36) | |

|

|

| Place of birth | New Rumley, Ohio |

| Place of death | Little Bighorn, Montana |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/branch | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1861–76 |

| Rank | Major General of Volunteers

Lieutenant Colonel (Regular Army) |

| Commands held | Michigan Brigade 7th U.S. Cavalry |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War

|

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. At the start of the Civil War, Custer was a cadet at the United States Military Academy at West Point, and his class's graduation was accelerated so that they could enter the war. Custer graduated last in his class and served at the First Battle of Bull Run as a staff officer for Major General George B. McClellan in the Army of the Potomac's 1862 Peninsula Campaign. Early in the Gettysburg Campaign, Custer's association with cavalry commander Major General Alfred Pleasonton earned him promotion from First Lieutenant to Brigadier General of United States Volunteers at the age of 23.[1]

Custer established a reputation as an aggressive cavalry brigade commander willing to take personal risks by leading his Michigan Brigade into battle, such as the mounted charges at Hunterstown and East Cavalry Field at the Battle of Gettysburg. In 1864, with the Cavalry Corps under the command of Major General Philip Sheridan, Custer led his "Wolverines", and later a division, through the Overland Campaign, including the Battle of Trevilian Station, where Custer was humiliated by having his division trains overrun and his personal baggage captured by the Confederates. Custer and Sheridan defeated the Confederate army of Lieutenant General Jubal A. Early in the Valley Campaigns of 1864. In 1865, Custer played a key role in the Appomattox Campaign, with his division blocking General Robert E. Lee's retreat on its final day.[2]

At the end of the Civil War (April 15, 1865), Custer was promoted to Major General of United States Volunteers.[1] In 1866, he was appointed to the Regular U.S. Army rank of Lieutenant Colonel, leading the 7th U.S. Cavalry and served in the Indian Wars. His distinguished war record, which started with riding dispatches for General Scott, has been overshadowed in history by his role and fate in the Indian Wars. Custer was defeated and killed at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876, against a coalition of Native American tribes composed almost exclusively of Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors, and led by the Sioux warrior Crazy Horse and the Sioux chiefs Gall and Sitting Bull. This confrontation has come to be popularly known in American history as Custer's Last Stand.

Contents |

Birth and family

Custer was born in New Rumley, Ohio, to Emanuel Henry Custer (1806–1892), a farmer and blacksmith, and Marie Ward Kirkpatrick (1807–1882).[3] Throughout his life Custer was known by a variety of nicknames. He was called alternately "Autie" (his early attempt to pronounce his middle name) and Armstrong. The names "Curley" and "Jack" (a phonetic name for his initials GAC which was on his satchel) were used by his troops. When he went west, the Plains Indians called him "Yellow Hair" and "Son of the Morning Star." His brothers Thomas Custer and Boston Custer died with him at the Battle of the Little Big Horn, as did his brother-in-law, James Calhoun, and nephew, Henry Armstrong "Autie" Reed. His other full siblings were Nevin Custer and Margaret Custer; he also had several older half-siblings.

The Custer family had emigrated to America in the late 17th Century from Westphalia, Germany. Their surname originally was "Küster". George Armstrong Custer was a great-great-grandson of Arnold Küster from Kaldenkirchen, Duchy of Jülich (today North Rhine-Westphalia state), who settled in Hanover, Pennsylvania.

Custer's mother's maiden name was Marie Ward. At the age of 16, she married Israel Kirkpatrick, who died in 1835. She married Emanuel Henry Custer in 1836. Marie's grandparents, George Ward (1724–1811) and Mary Ward (née Grier) (1733–1811), were from County Durham, England. Their son James Grier Ward (1765–1824) was born in Dauphin, Pennsylvania and married Catherine Rogers (1776–1829), and their daughter, Marie Ward, was Custer's mother. Catherine Rogers was a daughter of Thomas Rogers and Sarah Armstrong. According to family letters in The Custer Story, Custer was named after George Armstrong, a minister, in the hopes of his devout father that his son might become part of the clergy.

Early life

Custer spent much of his boyhood living with his half-sister and his brother-in-law in Monroe, Michigan, where he attended school and is now honored by a statue in the center of town.[4] Before entering the United States Military Academy, Custer attended the McNeely Normal School, later known as Hopedale Normal College, in Hopedale, Ohio, and known as the first co-educational college for teachers in eastern Ohio. While attending Hopedale, Custer, together with classmate William Enos Emery, was known to have carried coal to help pay for their room and board. Custer graduated from McNeely Normal School in 1856 and taught school in Ohio.

Custer was graduated a year early, last of 34 cadets[5] in the Class of 1861 from the United States Military Academy, just after the start of the Civil War.[6] Ordinarily, such a showing would be a ticket to an obscure posting and mundane career, but he had the fortune to graduate just as the war caused the army to experience a sudden need for new officers. His tenure at the Academy was a rocky one, and he came close to expulsion each of his four years due to excessive demerits, many from pulling pranks on fellow cadets.

Civil War

McClellan and Pleasonton

Custer was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Cavalry and immediately joined his regiment at the First Battle of Bull Run, where Army commander Winfield Scott detailed him to carry messages to Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell. After the battle he was reassigned to the 5th U.S. Cavalry, with which he served through the early days of the Peninsula Campaign in 1862. During the pursuit of Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston up the Peninsula, on May 24, 1862, Custer persuaded a colonel to allow him to lead an attack with four companies of Michigan infantry across the Chickahominy River above New Bridge. The attack was successful, resulting in the capture of 50 Confederates. Major General George B. McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac, termed it a "very gallant affair," congratulated Custer personally, and brought him onto his staff as an aide-de-camp with the temporary rank of captain. In this role, Custer began his life-long pursuit of publicity. On one occasion when McClellan and his staff were reconnoitering a potential crossing point on the Chickahominy River, they stopped and Custer overheard his commander mutter to himself, "I wish I knew how deep it is." Custer dashed forward on his horse out to the middle of the river and turned to the astonished officers of the staff and shouted triumphantly, "That's how deep it is, General!"[7]

When McClellan was relieved of command in November 1862, Custer reverted to the rank of First Lieutenant. Custer fell into the orbit of Major General Alfred Pleasonton, who was commanding a cavalry division. The general was Custer's introduction to the world of extravagant uniforms and political maneuvering, and the young lieutenant became his protégé, serving on Pleasonton's staff while continuing his assignment with his regiment. Custer was quoted as saying that "no father could love his son more than General Pleasonton loves me." After the Battle of Chancellorsville, Pleasonton became the commander of the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac and his first assignment was to locate the army of Robert E. Lee, moving north through the Shenandoah Valley in the beginning of the Gettysburg Campaign. In his first command, Custer affected a showy, personalized uniform style that alienated his men, but he won them over with his readiness to lead attacks (a contrast to the many officers who would hang back, hoping to avoid being hit); his men began to adopt elements of his uniform, especially the red neckerchief. Custer distinguished himself by fearless, aggressive actions in some of the numerous cavalry engagements that started off the campaign, including Brandy Station and Aldie.

Brigade command and Gettysburg

On June 28, 1863, three days prior to the Battle of Gettysburg, General Pleasonton promoted Custer from lieutenant to brigadier general of volunteers.[1][8] Despite having no direct command experience, he became one of the youngest generals in the Union Army at age 23. Two captains—Wesley Merritt and Elon J. Farnsworth—were promoted along with Custer, although they did have command experience. Custer lost no time in implanting his aggressive character on his brigade, part of the division of Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick. He fought against the Confederate cavalry of J.E.B. Stuart at Hanover and Hunterstown, on the way to the main event at Gettysburg.

Custer's style of battle was often claimed to be reckless or foolhardy, but military planning was always the basis of every Custer "dash". As the Custer Story in Letters explained, "George Custer meticulously scouted every battlefield, gauged the enemies weak points and strengths, ascertained the best line of attack and only after he was satisfied was the "Custer Dash" with a Michigan yell focused with complete surprise on the enemy in routing them every time. One of his greatest attributes during the Civil War was what Custer wrote of as "luck" and he needed it to survive some of these charges.

At Hunterstown, in an ill-considered charge ordered by Kilpatrick against the brigade of Wade Hampton, Custer fell from his wounded horse directly before the enemy and became the target of numerous enemy rifles. He was rescued by the bugler of the 1st Michigan Cavalry, Norville Churchill, who galloped up, shot Custer's nearest assailant, and allowed Custer to mount behind him for a dash to safety.

One of many of Custer's finest hours in the Civil War was just east of Gettysburg on July 3, 1863. In conjunction with Pickett's Charge to the west, Robert E. Lee dispatched Stuart's cavalry on a mission into the rear of the Union Army. Custer encountered the Union cavalry division of David McM. Gregg, directly in the path of Stuart's horsemen. He convinced Gregg to allow him to stay and fight, while his own division was stationed to the south out of the action. At East Cavalry Field, hours of charges and hand-to-hand combat ensued. Custer led a mounted charge of the 1st Michigan Cavalry, breaking the back of the Confederate assault. Custer's brigade lost 257 men at Gettysburg, the highest loss of any Union cavalry brigade.[9]

Marriage

Custer married Elizabeth Clift Bacon (1842–1933) on February 9, 1864. Following the Battle of Washita River in November 1868, Custer was alleged (by Captain Frederick Benteen, chief of scouts Ben Clark, and Cheyenne oral tradition) to have had a sexual relationship during the winter and early spring of 1868–1869 with Monaseetah, daughter of the Cheyenne chief Little Rock (killed in the Washita battle).[10] Monahsetah gave birth to a child in January 1869, two months after the Washita battle; Cheyenne oral history also alleges that she bore a second child, fathered by Custer, in late 1869.[10]

The Valley and Appomattox

When the cavalry corps of the Army of the Potomac was reorganized under Major General Philip Sheridan in 1864, Custer took part in the various actions of the cavalry in the Overland Campaign, including the Battle of the Wilderness (after which he ascended to division command), the Battle of Yellow Tavern, where Jeb Stuart was mortally wounded, and the Battle of Trevilian Station, where Custer was humiliated by having his division trains overrun and his personal baggage captured by the enemy. When Confederate Lieutenant General Jubal A. Early moved down the Shenandoah Valley and threatened Washington, D.C., Custer's division was dispatched along with Sheridan to the Valley Campaigns of 1864. They pursued the Confederates at Third Winchester and effectively destroyed Early's army during Sheridan's counterattack at Cedar Creek.

Custer and Sheridan, having defeated Early, returned to the main Union Army lines at the Siege of Petersburg, where they spent the winter. In April 1865 the Confederate lines were finally broken and Robert E. Lee began his retreat to Appomattox Court House, pursued by the Union cavalry. Custer distinguished himself by his actions at Waynesboro, Dinwiddie Court House, and Five Forks. His division blocked Lee's retreat on its final day and received the first flag of truce from the Confederate force. Custer was present at the surrender at Appomattox Court House and the table upon which the surrender was signed was presented to him as a gift for his gallantry. Before the close of the war Custer received brevet promotions to Brigadier General and Major General in the Regular Army (March 13, 1865) and Major General of volunteers (April 15, 1865).[5] As with most wartime promotions, even when issued under the Regular Army, these senior ranks were normally only temporary.

Indian Wars

On February 1, 1866, Custer was mustered out of the volunteer service and returned to his permanent rank of captain in the Regular Army, assigned to the 5th U.S. Cavalry. Custer took an extended leave, exploring options in New York City,[11] where he considered careers in railroads and mining.[12] Offered a position as adjutant general of the army of Benito Juárez of Mexico, who was then in a struggle with the self-proclaimed Maximilian I (a foil of French Emperor Napoleon III), Custer applied for a one-year leave of absence from the U.S. Army, but his appointment was blocked by U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward, who feared offending France.[12]

Following the death of his father-in-law in May 1866, Custer returned to Monroe, Michigan, where he considered running for Congress and took part in public discussion over the treatment of the American South in the aftermath of the Civil War, advocating a policy of moderation.[12] In September 1866 he accompanied President Andrew Johnson on a journey by train to build up public support for Johnson's policies towards the South. Custer denied a charge by the newspapers that Johnson had promised him a colonel's commission in return for his support, though Custer had written to Johnson some weeks before seeking such a commission.[13]

Custer was appointed Lieutenant Colonel of the newly created U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment,[14] headquartered at Fort Riley, Kansas.[15] As a result of a plea by his patron General Philip Sheridan, Custer was also recipient of a Brevet rank of Major General.[14] He then took part in General Winfield Scott Hancock's expedition against the Cheyenne in 1867.

His career took a brief detour following the Hancock campaign when he was court-martialed at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas for being AWOL, after abandoning his post to see his wife, and was suspended for duty for one year. He returned to duty in 1868, before his term of suspension had expired, at the request of General Philip Sheridan, who wanted Custer for his planned winter campaign against the Cheyenne.

Under Sheridan's orders, Custer took part in establishing Camp Supply in Indian Territory in early November 1868 as a supply base for the winter campaign. Custer then led the 7th U.S. Cavalry in an attack on the Cheyenne encampment of Black Kettle – the Battle of Washita River on November 27, 1868. Custer reported killing 103 warriors, though estimates by the Cheyenne themselves of the number of Indian casualties were substantially lower; some women and children were also killed, and 53 women and children were taken prisoner. Custer had his men shoot most of the 875 Indian ponies the troops had captured. This was regarded as the first substantial U.S. victory in the Comanche War, helping to force a significant portion of the Southern Cheyennes onto a U.S. appointed reservation.

In 1873, he was sent to the Dakota Territory to protect a railroad survey party against the Sioux. On August 4, 1873, near the Tongue River, Custer and the 7th U.S. Cavalry clashed for the first time with the Sioux. Only one man on each side was killed. In 1874, Custer led an expedition into the Black Hills and announced the discovery of gold on French Creek near present-day Custer, South Dakota. Custer's announcement triggered the Black Hills Gold Rush and gave rise to the lawless town of Deadwood, South Dakota.

Battle of the Little Bighorn

By the time of Custer's expedition to the Black Hills in 1874, the level of conflict and tension between the U.S. and many plains Indians tribes (including the Lakota Sioux and the Cheyenne) had become exceedingly high. Indians killed settlers and railroad workers, Americans continually broke treaty agreements and advanced further westward. To take possession of the Black Hills (and thus the gold deposits), and to stop Indian attacks, the U.S. decided to corral all remaining free plains Indians. The Grant government set a deadline of January 31, 1876 for all Lakota and Northern Cheyenne to report to their designated agencies (reservations) or be considered "hostile."

The 7th Cavalry departed from Fort Lincoln on May 17, 1876, part of a larger army force planning to round up remaining free Indians. Meanwhile, in the spring and summer of 1876, the Hunkpapa Lakota chief Sitting Bull had called together the largest ever gathering of plains Indians at Ash Creek, Montana (later moved to the Little Bighorn River) to discuss what to do about the whites.[16] It was this united encampment of Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho Indians that the 7th met at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

On June 25, some of Custer's Crow Indian scouts identified what they claimed was a large Indian encampment along the Little Bighorn River. Custer divided his forces into three battalions: one led by Major Marcus Reno, one by Captain Frederick Benteen, and one by himself. Captain Thomas M. McDougall and Company B were with the pack train. Benteen was sent south and west, to cut off any attempted escape by the Indians, Reno was sent north to charge the southern end of the encampment, and Custer rode north, hidden to the east of the encampment by bluffs, and planning to circle around and attack from the north.[17][18]

Reno began a charge on the southern end of the village, but halted midway and had his men dismount and form a skirmish line.[19][18] They were soon overcome by mounted Lakota and Cheyenne warriors who counterattacked en masse against Reno's exposed left flank [20] forcing Reno and his men to take cover in the trees along the river. Eventually, however, this position became untenable and the troopers were forced into a bloody retreat up onto the bluffs above the river, where they made their own stand.[21][22] This, the opening action of the battle, cost Reno a quarter of his command.

Meanwhile, unaware of Reno's failure, Custer had his command to the northern end of the main encampment, where he apparently planned to sandwich the Indians between his attacking troopers and Reno's command in a "hammer-and-anvil" maneuver. According to Grinnell's account, based on the testimony of the Cheyenne warriors who survived the fight,[23] at least part of Custer's command attempted to ford the river at the north end of the camp but were driven off by stiff resistance from the Indians and were pursued by hundreds of warriors onto a ridge north of the encampment. There, Custer was prevented from digging in by Crazy Horse, whose warriors had outflanked him and were now to his north, at the crest of the ridge.[24] Traditional white accounts attribute to Gall the attack that drove Custer up onto the ridge, but Indian witnesses have disputed that account.[25]

For a time, Custer's men were deployed by company, in standard cavalry fighting formation—the skirmish line, with every fourth man holding the horses. This arrangement, however, robbed Custer of a quarter of his firepower, and as the fight intensified, many soldiers took to holding their own horses or hobbling them, further reducing their effective fire. When Crazy Horse and White Bull mounted the charge that broke through the center of Custer's lines, pandemonium broke out among the men of Calhoun's command,[26] though Keogh's men seem to have fought and died where they stood. Many of the panicking soldiers threw down their weapons[27] and either rode or ran towards the knoll where Custer the other officers and about 40 men were making a stand. Along the way, the Indians rode them down, counting coup by whacking the fleeing troopers with their quirts or lances.[28]

Initially, Custer had 208 officers and men under his command, with an additional 142 under Reno and just over a hundred under Benteen. The Indians fielded over 1800 warriors.[29] As the troopers were cut down, the Indians stripped the dead of their firearms and ammunition, with the result that the return fire from the cavalry steadily decreased, while the fire from the Indians steadily increased. With Custer and the survivors shooting the remaining horses to use them as breastworks and making a final stand on the knoll at the north end of the ridge, the Indians closed in for the final attack and killed all in Custer's command. As a result, the Battle of the Little Bighorn has come to be popularly known as "Custer's Last Stand."

When the cavalry's main column did arrive three days later, they found most of the soldiers' corpses stripped, scalped, and mutilated.[30] Custer’s body had two bullet holes, one in the left temple and one just above the heart.[31] Following the recovery of Custer's body, he was given a funeral with full military honors and buried on the battlefield. He was reinterred in the West Point Cemetery on October 10, 1877. The battle site was designated a National Cemetery in 1876.

Controversial legacy

After his death, Custer achieved the lasting fame that he had sought on the battlefield. The public saw him as a tragic military hero and exemplary Victorian gentleman who sacrificed his life for his country. Custer's wife, Elizabeth, who accompanied him in many of his frontier expeditions, did much to advance this view with the publication of several books about her late husband: Boots and Saddles, Life with General Custer in Dakota (1885), Tenting on the Plains (1887), and Following the Guidon (1891). General Custer himself wrote about the Indian wars in My Life on the Plains (1874).

Today Custer would be called a "media personality" who understood the value of good public relations and leveraged media effectively; he frequently invited correspondents to accompany him on his campaigns (one died with him at the Little Bighorn), and their favorable reportage contributed to his high reputation that lasted well into the 20th century. After being promoted to brigadier general in the Civil War, Custer sported a uniform that included shiny jackboots, tight olive-colored corduroy trousers, a wide-brimmed slouch hat, tight hussar jacket of black velveteen with silver piping on the sleeves, a sailor shirt with silver stars on his collar, and a red cravat. He wore his hair in long glistening ringlets liberally sprinkled with cinnamon-scented hair oil. Later in his campaigns against the Indians, Custer wore a buckskin outfit along with his familiar red tie.

The assessment of Custer's actions during the Indian Wars has undergone substantial reconsideration in modern times. For many critics, Custer was the personification of the U.S. Government's ill-treatment of the Native American tribes, while others see him as a scapegoat for the Grant Indian policy, which he personally opposed. His testimony on behalf of the abuses sustained by the reservation Indians nearly cost him his command by the Grant administration. Custer once wrote that if he were an Indian, he would rather fight for his freedom alongside the hostile warriors "than be confined to the limits of a reservation".

Many criticized Custer's actions during the battle of the Little Bighorn, claiming his actions were impulsive and foolish, while others praised him as a fallen hero who was betrayed by the incompetence of his subordinate officers. The controversy over who is to blame for the disaster at Little Bighorn continues to this day. Maj. Reno's failure to press his attack on the south end of the Lakota/Cheyenne village and his flight to the timber along the river after a single casualty have been cited as a causative factor in the destruction of Custer's battalion, as has Capt. Benteen's allegedly tardy arrival on the field and the failure of the two officers' combined forces to move toward the relief of Custer.

In contrast, critics, from that time until the present, have asserted at least three military blunders. First, while camped at Powder River, Custer refused the support offered by General Terry on June 21, of an additional four companies of the Second Cavalry. Custer stated that he "could whip any Indian village on the Plains" with his own regiment, and that extra troops would simply be a burden.

At the same time, he left behind at the steamer Far West on the Yellowstone a battery of Gatling guns, knowing he was facing superior numbers. Before leaving the camp all the troops, including the officers, also boxed their sabers and sent them back with the wagons.[32]

Finally, on the day of the battle, Custer divided his 600-man command in the face of superior numbers. So, reducing the size of his force by at least a sixth, and rejecting the firepower offered by the Gatling guns played into the events of June 25 to the disadvantage of the 7th cavalry.[33]

But, Gatling guns were known to be fragile, and thus temperamental. To Custer, speed in gaining the battlefield was essential and of more importance. Too, splitting his force was a standard tactic, so as to demoralize the enemy with the appearance of the cavalry in different places all at once, especially when a contingent threatened the line of retreat. The arguments over Custer's tactics began even before the battle was joined, and have continued since.

Monuments and memorials

* Counties are named in Custer's honor in five states: Colorado, Montana, Nebraska, Oklahoma and South Dakota. Custer County, Idaho, is named for the General Custer mine, which, in turn, was named after Custer. There are several townships named for Custer in Minnesota and Michigan. There are also the towns of Custer, Michigan, Custer, South Dakota, Custar, Ohio, and the unincorporated town of Custer, Wisconsin. A portion of Monroe County, Michigan, is informally referred to as "Custerville." [1]

- Custer National Cemetery is within Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, the site of Custer's death.

- There is an equestrian statue of Custer in Monroe, Michigan, his boyhood home. Originally located near city hall, in the center of town, it was moved years later to Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Park, a small park near the River Raisin and away from the main thoroughfares of the city. Due to lobbying by Libbie Custer and others, it was eventually moved to its current location, on the corner of Monroe and Elm Streets, on the edge of downtown Monroe.

- Fort Custer National Military Reservation, near Augusta, Michigan, was built in 1917 on 130 parcels of land, mainly small farms leased to the government by the local chamber of commerce as part of the military mobilization for World War I. During the war, some 90,000 troops passed through Camp Custer. Following the Armistice of 1918, the camp became a demobilization base for over 100,000 men. In the years following World War I, the camp was used to train the Officer Reserve Corps and the Civilian Conservation Corps. On August 17, 1940, Camp Custer was designated Fort Custer and became a permanent military training base. During World War II, more than 300,000 troops trained there, including the famed 5th Infantry Division (also known as the "Red Diamond Division") which left for combat in Normandy, France, June 1944. Fort Custer also served as a prisoner of war camp for 5,000 German soldiers until 1945. Today Fort Custer's training facilities are used by the Michigan National Guard and other branches of the armed forces, primarily from Ohio, Illinois, and Indiana. Many Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) students from colleges in Michigan, Ohio, Illinois, and Indiana also train at this facility, as well as do the FBI, the Michigan State Police, and various other law enforcement agencies. (https://www.mi.ngb.army.mil/ftcuster/default.asp)

- The establishment of Fort Custer National Cemetery (originally Fort Custer Post Cemetery) took place on September 18, 1943, with the first interment. As early as the 1960s, local politicians and veterans organizations advocated the establishment of a national cemetery at Fort Custer. The National Cemeteries Act of 1973 directed the Veterans' Administration to develop a plan to provide burial space to all veterans who desired interment in a national cemetery. After much study, the NCS adopted what became the regional concept. Fort Custer became the Veterans' Administration's choice for its Region V national cemetery. Toward this goal, Congress created Fort Custer National Cemetery in September 1981. The cemetery received 566 acres (2.29 km2) from the Fort Custer Military Reservation and 203 acres (0.82 km2) from the VA Medical Center. The first burial took place on June 1, 1982. At the same time, approximately 2,600 gravesites were available in the post cemetery, which made it possible for veterans to be buried there while the new facility was being developed. On Memorial Day 1982, more than 33 years after the first resolution had been introduced in Congress, impressive ceremonies marked the official opening of the cemetery.(http://www.cem.va.gov/nchp/ftcuster.htm)

- Custer Hill is the main troop billeting area at Fort Riley, Kansas.

- The US 85th Infantry Division was nicknamed The Custer Division.

- The Black Hills of South Dakota is full of evidence of Custer, with a county, town, and the Custer State Park all located in the area.

- Custer Observatory is the oldest observatory on Long Island. Located in Southold, New York, it was founded in 1927 by Charles Elmer (co-founder of the Perkin-Elmer Optical Company), along with a group of fellow amateur-astronomers. This name was chosen to honor the hospitality of Mrs. Elmer, formerly May Custer, the Grand Niece of General George Armstrong Custer.

- The Custer house at Fort Lincoln near present day Mandan North Dakota as it appeared during his stay there has been reconstructed along with the soldiers barracks, block houses, etc. There are re-enactments each year of Custer's 7th Cavalry leaving for the Little Big Horn.

- On July 2, 2008, a marble monument to Brigadier General Custer was dedicated at the site of the 1863 Civil War Battle of Hunterstown in Adams County, Pennsylvania.

See also

- List of American Civil War generals

- Cultural depictions of George Armstrong Custer

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "George Armstrong Custer – Little Bighorn Battlefield NM". National Park Service (2000). Retrieved on 2008-05-25.

- ↑ Dellenbaugh, Frederick Samuel (1917), George Armstrong Custer, The Macmillan Company, pp. 71–81, http://books.google.com/books?id=e0cDAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA71&lpg=PA71&dq=Custer+Appomattox+&source=web&ots=6vXRZp50_3&sig=2zef4uer33chlmvCWFvzLzIx_CE&hl=en, retrieved on 2008-03-16

- ↑ Custer in the 1850 US Census in North Township, Ohio

- ↑ Boston Custer in the 1870 US Census in Monroe, Michigan

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Eicher, p. 196.

- ↑ Custer in the 1860 US Census at West Point

- ↑ Tagg, p. 184.

- ↑ Third Pennsylvania Cavalry Association (1905), History of the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry, Sixtieth Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers in the Civil War 1861-1865, Franklin Printing Co., p. 250–251, http://books.google.com/books?id=_FohAAAAMAAJ&dq=custer+%22united+states+volunteers%22&source=gbs_summary_s&cad=0

- ↑ Tagg, p. 185.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Utley 2001, p. 107.

- ↑ Utley 2001, p. 38.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Utley 2001, p. 39.

- ↑ Utley 2001, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Utley 2001, p. 40.

- ↑ Utley 2001, p. 41.

- ↑ Marshall 2007, pg. 15

- ↑ Welch 2007, pg. 149

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Ambrose 1996, pg. 437

- ↑ Marshall 2007, pg. 2

- ↑ Testimony of Trooper Billy Jackson, in Goodrich, Thomas. Scalp Dance: Indian Warfare on the High Plains, 1865-1879. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1997. p. 242

- ↑ Marshall 2007, pg. 4

- ↑ Ambrose 1996, pg. 439

- ↑ Grinnell, 1915, pp. 300–301

- ↑ Marshall 2007, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ cf. Michno, 1997, p. 168.

- ↑ Michno, 1997, pp. 205–206

- ↑ Welch 2007, pg. 183; cf. Grinnell, p. 301, whose sources say that by this time, about half the soldiers were without carbines and fought only with six-shooters.

- ↑ cf. Michno, 1997. pp. 205–206: testimony of White Bull; p. 215: testimony of Yellow Nose.

- ↑ cf. Michno, 1997, pp. 10–20; Michno settles on a low number around 1000, but other sources place the number at 1800 or 2000, especially in the works by Utley and Fox. The 1800–2000 figure is substantially lower than the higher numbers of 3000 or more postulated by Ambrose, Gray, Scott and others.

- ↑ Marshall 2007, pg. 11; Welch 2007, pp. 175–181

- ↑ Welch 2007, pg. 175

- ↑ William Slaper's Story of the Battle Personal account by a trooper in M company 7th Calvary.

- ↑ Goodrich, Scalp Dance, 1997, pp. 233–234.

References

- Ambrose, Stephen E. (1996 [1975]). Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors. New York: Anchor Books.

- Eicher, John H. and David J. Eicher. (2001). Civil War High Commands. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Goodrich, Thomas. Scalp Dance: Indian Warfare on the High Plains, 1865-1879. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1997.

- Gray, John S. (1993). Custer’s Last Campaign: Mitch Boyer and the Little Bighorn Remembered. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-7040-2.

- Grinnell, George Bird (1915). 'The Fighting Cheyennes'. The University of Oklahoma Press reprint 1956. p. 296–307. ISBN 0-7394-0373-7.

- Longacre, Edward G. (2000). Lincoln's Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of the Potomac. Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-1049-1.

- Mails, Thomas E. Mystic Warriors of the Plains. New York: Marlowe & Co., 1996.

- Marshall, Joseph M. III. (2007). The Day the World Ended at Little Bighorn: A Lakota History. New York: Viking Press.

- Merington, Marguerite, Ed. The Custer Story: The Life and Intimate Letters of General Custer and his Wife Elizabeth. (1950)

- Michno, Gregory F. (1997). Lakota Noon: The Indian Narrative of Custer's Defeat. Mountain Press Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8784-2349-4.

- Perrett, Bryan. Last Stand: Famous Battles Against the Odds. London: Arms & Armour, 1993.

- Scott, Douglas D., Richard A. Fox, Melissa A. Connor, and Dick Harmon. (1989). Archaeological Perspectives on the Battle of the Little Bighorn. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3292-2.

- Punke, Michael, "Last Stand: George Bird Grinnell, the Battle to Save the Buffalo, and the Birth of the New West", Smithsonian Books, 2007, ISBN 978 0 06 089782 6

- Tagg, Larry. (1988). The Generals of Gettysburg. Savas Publishing. ISBN 1-882810-30-9.

- Urwin, Gregory J. W., Custer Victorious, University of Nebraska Press, 1990, ISBN 978-0803295568.

- Utley, Robert M. (2001). Cavalier in Buckskin: George Armstrong Custer and the Western Military Frontier, revised edition. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3387-2.

- Vestal, Stanley. Warpath: The True Story of the Fighting Sioux Told in a Biography of Chief White Bull. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1934.

- Warner, Ezra J. (1964). Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-0822-7.

- Welch, James, with Paul Stekler. (2007 [1994]). Killing Custer: The Battle of Little Bighorn and the Fate of the Plains Indians. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Wert, Jeffry D. Custer: The controversial life of George Armstrong Custer. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1964/1996. ISBN 0-684-83275-5.

- Wittenberg, Eric J. (2001). Glory Enough for All : Sheridan's Second Raid and the Battle of Trevilian Station. Brassey's Inc. ISBN 1-57488-353-4.

Further reading

- Newsom TM (2007). History: Thrilling scenes among the Indians. With a graphic description of Custer's last fight with Sitting Bull. Kessinger Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-0548629888. http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/History/History-idx?id=History.Newson. Retrieved on 2008-03-09.

- Victor FF (1877). History: Thrilling scenes among the Indians. With a graphic description of Custer's last fight with Sitting Bull. Columbian book company. http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/History/History-idx?id=History.Victor. Retrieved on 2008-03-09.

- Whittaker F (1876). A complete life of Gen. George A. Custer : Major-General of Volunteers; Brevet Major-General, U.S. Army; and Lieutenant-Colonel, Seventh U.S. Cavalry. Sheldon and Company. http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/History.Whittaker. Retrieved on 2008-03-09.

- Finerty JF (1890). War-path and bivouac : or, The conquest of the Sioux : a narrative of stirring personal experiences and adventures in the Big Horn and Yellowstone expedition of 1876, and in the campaign on the British border, in 1879. Donohue Brothers. http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/History.Finerty. Retrieved on 2008-03-09.

External links

- Custer Battlefield Museum

- George Armstrong Custer at Find A Grave Retrieved on 2008-02-12

- Little Bighorn History Alliance

- Custerwest.org:Site For Traditional Scholarship

- Kenneth M Hammer Collection on Custer and the Battle of the Little Big Horn, University of Wisconsin-Whitewater

- Gallery of Custer images

|

||||||||||||||

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Custer, George Armstrong |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | United States Army cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the Indian Wars |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 5, 1839 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | New Rumley, Ohio, United States |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 25, 1876 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Little Big Horn, Montana, United States |