Genealogy of Jesus

The genealogy of Jesus through Joseph is given by two passages from the Gospels, Matthew 1:2–16 and Luke 3:23–38. Both of them trace Jesus' line back to King David (a prophetic requisite for the Christ[1]) and from there on to Abraham; Luke traces the line all the way back to Adam. These lists are identical between Abraham and David, but they differ radically from that point onward.

The differences between Matthew's and Luke's genealogy has been a problem for both ancient and modern rationalist readers of the Gospels. According to Howard W. Clarke, the two accounts cannot be harmonized and today the genealogy accounts are generally taken to be "theological" constructs. More specifically, some have suggested that Matthew wants to underscore birth of a messianic child of royal lineage (mentioning Solomon) whereas Luke's genealogy is priestly (mentioning Levi).[2][3] According to Scott Gregory Brown, the reason for the difference between the two genealogies is that it was not included in the written accounts that the writers of the two Gospels shared (i.e. Gospel of Mark and the Q Document).[4]

According to Stanton, the genealogy foreshadows acceptance of Gentiles into the Kingdom of God: in reference to Jesus as 'the Son of Abraham', the author has in mind the promise given to Abraham in Gen 22:18. Matthew holds that due to Israel's failure to produce the "fruits of the kingdom" and her rejection of Jesus, God's kingdom is now taken away from Israel and given to Gentiles. Another foreshadowing of the acceptance of Gentiles is the inclusion of four women in the genealogy, something unexpected to a first century reader. According to Stanton, women are probably representing non-Jews to a first century reader. [5] According to Markus Bockmuehl et al, Matthew is mentioning this to prepare its reader for the apparent scandal surrounding Jesus' birth by emphasizing on the point that God's purpose is sometimes worked out in unorthodox and surprising ways. [6]

Contents |

Texts

Matt 1:1–6 and Luke 3:32–34 (in agreement)

- Abraham

- Isaac

- Jacob

- Judah

- Pharez (Perez)

- Hezron

- Ram (Aram)

- Amminadab

- Nahshon

- Salma (Salmon)

- Boaz

- Obed

- Jesse

- David

|

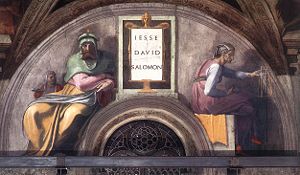

Michelangelo's Jesse-David-Solomon. David is generally seen as the man on the left with Solomon the child behind him.

Michelangelo's Josiah-Jechoniah-Sheatiel. Josiah is generally seen as the man on the right with Jechoniah being the child on his knee. The boy being held by the woman is intended as one of Jechoniah's brothers.

Michaelangelo's Jacob - Joseph.

|

Variations

The Gospels of Matthew and Luke give different accounts of Jesus' genealogy.[7] Both trace his ancestors back to Abraham through King David but via different sons of King David: King Solomon and Nathan, respectively. Thus, the lines differ between David and Jesus's father Joseph. Since antiquity, scholars have disagreed about the significance of the two genealogies.

Matthew's genealogy involves Jesus's title "Christ", in the sense of an "anointed" king. It starts with Solomon and proceeds through the kings of Judah up to and including Jeconiah. A few of the Judean kings are left out, though. For instance; Azariah/Uzziah is given as the son of Jehoram/Joram thus skipping four generations.[8] In Old Testament times, many records were also abridged.[9] Thus Jesus is established as legal heir to the throne of Israel. At Jeconiah the line of kings was terminated due to Israel being conquered by Babylonians. The names continue with Jeconiah's son and his grandson Zerubbabel, who is a notable figure in the Book of Ezra. The names between Zerubbabel and Joseph do not appear anywhere in the Old Testament or other texts, with a couple of exceptions. At the conclusion, Jesus being identified as a new king is called "Christ".

Alternatively, Luke's genealogy descends through Nathan, who is an otherwise little-known son of King David, mentioned once in the Hebrew Bible,[10] with only an indirect claim to the Davidic throne. Because each generation averages about 25 years,[11] including children who are not firstborn, Luke's list of 40 generations between David and Joseph approximates a realistic one thousand years. By contrast, Matthew's list of 25 generations is too short and can only represent a "telescoped", schematized or otherwise interrupted line.

Luke's genealogy involves Jesus's title "son of God" in the sense of being a descendant of Adam who was created by God. Luke opens the genealogy with the heavenly voice at Jesus' baptism saying, "You are my son", and concludes it with the addition of earlier ancestors before Abraham back to Adam, who is called "son of God".

Explanations for discrepancies

| A series of articles on |

|---|

|

Jesus Christ and Christianity |

|

Cultural and historical background |

|

Perspectives on Jesus |

|

Jesus in culture |

Several theories have been proposed to explain the discrepancies between Matthew and Luke:

- The oldest one, ascribed to Julius Africanus[12], uses the concept of Levirate marriage, and suggests that Matthan (grandfather of Joseph according to Matthew), and Matthat (grandfather of Joseph according to Luke), were brothers, married to the same woman one after another—this would mean that Matthan's son (Jacob) could be Joseph's biological father, and Matthat's son (Heli), was his legal father.

- That Luke's genealogy is of Mary, with Heli being her father, while Matthew's describes the genealogy of Joseph. [13]

- That at least one, and possibly both, of the genealogies are simply fabricated, thus explaining the divergence.[14]

- According to Barbara Thiering in her book Jesus the man, Jacob and Heli are one and the same. Heli took the name "Jacob" for his title as patriarch. The true genealogy is that in Luke's gospel, and in Matthew's gospel Heli's line is grafted in to the royal line running down through Solomon. (It should be noted that Thiering's theories have found little acceptance with either secular or religious academia).

Levirate marriage

The earliest Christian tradition that explains this discrepancy records a complex scenario that involves the Jewish custom of Levirate marriage. Augustine learned this tradition from Julius Africanus and accepted it as authoritative. (Eusebius of Caesaria, Church History 1:7, 6:31; Augustine of Hippo, De Consensu Evangelistarum 2.)

- Christian tradition identifies a woman named Estha as the grandmother of Joseph. She married Mathan, a descendant of David through Solomon, and by him became the mother of Jacob.

- However after Mathan died, she remarried and by her second husband Mathat, a descendant of David through Nathan, became the mother of Heli.

- Therefore, Jacob and Heli are half-brothers who have the same mother.

- Heli married, but died without children. So his widow undertook the ancient custom of a levirate marriage, and married the brother Jacob to give her children in Heli's name. She birthed Joseph.

- Therefore, Joseph is both the biological son of Jacob (from Solomon) and the legal son of Heli (from Nathan). Therefore, two genealogies have been preserved.

- While being the legal son of Heli, Joseph and his mother remained in the household of Jacob, according to custom, and Joseph legally inherited from Jacob.

Heli

The confusion over the name of Joseph’s father encouraged explanations to reconcile the two genealogies. One suggestion [15] assigns Luke's genealogy to Jesus's mother Mary, and not to his father Joseph at all. So Jacob would be the father of Joseph, and Heli the father of Mary. Therefore, no contradiction.

The use of the term 'son' was often used in the sense of a 'descendant' or a head of a household's relative living under the same roof. An example of this in the Hebrew Bible would be Manasseh, who was described in Numbers 32:41, Deuteronomy 3:14 and 1st Kings 4:13 as the 'son' of Jair. However, it is revealed in 1st Chronicles 2:21-23 and 7:14-15 that he is actually the distant son-in-law of Jair. Thus calling Jesus the 'son of Joseph' could be interpreted to mean Jesus was a member of Joseph's household without being a biological son.

Assuming a virgin birth through Mary, Jesus's patrilinear genealogy could follow Mary's father. (A similar legal scenario was in place for the ancient concubines whose children did not inherit their father's property, but instead inherited property from their mother's father.)

The suggestion focuses on the language of Luke's Greek text. Luke adds a phrase that today would be considered a parenthetical comment. Luke 3:23 says literally: "And Jesus himself was ... a son (being thought) of Joseph of Heli" (Greek: και αυτος ην ιησους ... υιος ως ενομιζετο ιωσηφ του ηλι). The plain meaning of the text is usually understood as communicating the notion that Jesus was believed to be the son of Joseph but was actually the product of virgin birth. The suggestion simply expands the parenthesis to literally comment Joseph out of the genealogy altogether. "And Jesus himself was ... a son (being thought of Joseph) of Heli". In other words, people believed Jesus was the son of Joseph, but really he was the son of Mary's father Heli. Thus Joseph would be irrelevant to this genealogy.

The suggestion accepts the accuracy of the exact wording of the biblical text, it resolves an apparent contradiction between two biblical texts, and it expands the reputation of Jesus's mother Mary by explicating her aristocratic origins all the way back to King David.

Nevertheless, the genealogy does not actually mention Mary: making it her genealogy is therefore a "daring" interpretation. More problematically, the Early Christians preserve no tradition identifying Luke's genealogy as Mary's. It was not until the 15th century AD, when Annius of Viterbo first suggested this reassignment of the genealogy to Mary, with it gaining popularity only in the following centuries since. Most scholars "safely" discount the possibility that the genealogy belongs to Mary.[16]

Admin and Arni

Instead of calling Amminadab son of Ram, who was a son of Hezron (1. Chr 2:9,10; Ruth 4:19, 20), the genealogy of Luke states: "…Amminadab, the son of Arni, the son of Hezron…" In some manuscripts the name Admin is inserted between Arni and Amminadab: "…Amminadab, the son of Admin, the son of Arni, the son of Hezron…" Most likely, Arni is a variant of the Greek equivalent of the name Ram. Ram is rendered Aram in Septuaginta. In many modern translations the name is rendered Aram in Matthew's genealogy. The name Admin can be a corruption of the name Amminadab, and the insertion of the name Admin is likened to be an error. Today, Bible translations vary on this issue, some have both Arni and Admin, some have only Arni, and yet some have Ram instead of Arni. Some also have Aram instead of Arni and Ram.

Curse on Jehoiakim

Jeremiah prophesied that King Jehoiakim would be killed by the enemy and no biological descendant of his would claim the throne. "Now this is what the LORD says about King Jehoiakim of Judah: He will have no heirs to sit on the throne of David. His dead body will be thrown out to lie unburied- exposed to the heat of the day and the frost of the night.". (Jeremiah 36:30.) Here is yet another problematic issue raised by the genealogies. However, the solution offered by many Christians [17] is this: Luke's genealogy, as seen by what may be considered linguistic evidence, is in fact Mary's, not Joseph's, and the record in Matthew is his. If this is the case, the point is continued, then God's curse is not undermined, seeing as how Jesus wasn't the biological son of Joseph.

Shealtiel and Zerubbabel

Although Shealtiel and his son Zerubbabel have unusual names, the ones who have these names in Luke's genealogy are sometimes explained to not be the same as the famous ones who have these names in Matthew's genealogy.[18] Matthew's Zerubbabel is the famous one who led the Jews back from Babylon to Jerusalem around 520 BCE, and who was perhaps born around 570 BCE. By contrast, if each generation is about 25 (or 23.8) years, then Luke's Zerubbabel was born around 502 (or 478) BCE. In other words, Luke's Shealtiel lived about three or four generations after the famous Shealtiel. Thus, he could be named after the famous one and likewise named his own son after his famous son Zerubbabel. The famous names frequent the later books in the Hebrew Bible, with positive connotations of restoration from disaster. As different people, there would be no contradiction between the famous Shealtiel's father being King Jeconiah/Jehoiachin in Matthew but an otherwise unknown Neri in Luke, and likewise the famous Zerubbabel's son being Abiud in Matthew but Rhesa in Luke. Another suggestion, however, is that they are in fact the same persons, and that Neri was Shealtiel's father in law.

The sons of Zerubbabel

The book of Chronicles mentions numerous children of Zerubbabel, but neither Abiud nor Rhesa is in this list. Some scholars suggest this section appears garbled by scribal errors. By extension, if a genealogical list survived elsewhere, it may have mentioned Abiud as part of the original list. Some think that Abiud could be identical with Meshullam, who is listed as the first son of Zerubbabel. Or he could be a descendant of Zerubbabel, but not his immediate son. One explanation is that Abiud can be the same as Joda in Luke's genealogy, which would mean that the two genealogies have some generations in common. Alternatively, Abiud may not be Zerubbabel's biological descendent but a son in some other sense, such as Levirate marriage. A non-biological inheritor would bypass the curse on Jehoiakim, and enable Abiud to be part of a list of eligible claimants to sit on a restored throne of David (another solution offered in regards to Joseph's apparent entanglement in the curse due to his family line.) Some have thought that Rhesa could be Zerubbabel's son in law. Or either Rhesa or Abiud could be a son in law. Another possibility is that Rhesa could be another name of one of Zerubbabel's sons, born during the Persian time. Some have pointed out that Rhesa can be derived from a Persian word meaning "prince", which would be fit for someone born in a family with royal ancestry.

Brevity

Amongst others, Raymond E. Brown has remarked that Matthew's genealogy seems to be moving much too quickly - it gives 12 generations between King Jechonias (alternate spellings: Jeconiah, Jehoiachin) of the Babylonian Exile of Judah of ca 595 BC and Joseph, giving an approximate average length of generation of 50 years, extremely long for an ancient genealogy. This first part of Matthew 1:8 coincides with the list of the Kings of Judah that is present in a number of other parts of the Bible. However these other lists have Jehoram's son being Ahaziah while Uzziah is a quite different monarch who lives several generations later. This means that Matthew's genealogy skips Ahaziah, Athaliah, Jehoash, and Amaziah.

Those who believe in the inerrancy of the Bible contend that the genealogy was never meant to be complete. The incompleteness would be consistent with the writing in Matthew, and not considered an error, such as Matthew 1:20 where Joseph is referred simply as "Son of David." It is possible then, that the author of Matthew deliberately dropped those who were not needed from the list, either because of a lack of significance or because, as others conjecture, because of a political motive.

One theory is that they were excised owing to their wickedness, or because they were murdered, but the even more unpleasant Ahaz, Manasseh and Amon are left in the list. Gundry supports the popular theory that these monarchs were left out because they were all descendants of Ahab, through his daughter Athaliah, both targets of a large degree of scorn in Jewish perception. Gundry also believes their removal was because the author was trying to contrive a division of the genealogy into three even divisions of fourteen names, hence contriving Jesus to seem to be the natural conclusion to the history.

As stated earlier, it was also quite common in the NT period to abridge and shorten genealogies for the sake of aiding memorisation. Many Christians and Bible scholars might claim that since the style was fairly common, Matthew had more than enough precedence to do so, also.

Albright and Mann have a different theory, though, proposing that the author, or a later scribe, made a common scribal transcription error, known as homoioteleuton, confusing Achaziah and Uzziah due to the similarity of their names. Under this proposal, the three divisions of fourteen names were not originally present, only discovered after the scribal error, with Matthew 1:17, which discusses this division, being a later addition to the text.

Luke's genealogy is considerably longer than is Matthew's, presenting a far more plausible number of names. That Luke goes through David's much less acclaimed son Nathan and does not include the kings of Israel in Jesus' lineage is also seen as adding to Luke's credibility. (Another key difference in the two is that while Matthew’s genealogy goes back to Abraham, Luke’s continues all the way back to Adam. The reason was likely because while Matthew’s audience was presumably Jews, and therefore he was concerned with showing the fulfillment of messianic prophecy, Luke’s was that of Greeks, and he would therefore be more interested in tracing Christ back to God, since the Gentiles would not be very concerned with Jewish prophecy.) However, while names in Matthew's genealogy match the historical period in which they are meant to have lived, the names on Luke's list seem to lack historical accuracy - Luke's names reflect names and spelling of the first century, rather than the periods in which the people actually lived.

Duplication, telescoping, and copying

Zadok is generally placed as having lived some 150 years after the start of Zerubbabel's period. This is a long period of time for just Zerubbabel, Abiud, Eliakim, and Azor to cover, and so many scholars feel an accurate list would be longer than Matthew's, more like Luke's genealogy, which has far more names for the period. That this part of the genealogy in Matthew lacks papponymics has led Albright and Mann to speculate that the original names covering this period became telescoped together, owing to repetitive re-occurrences of names; whereas Luke's genealogy contains several repeated groups of closely similar names, suggesting that Luke inadvertently, or deliberately, duplicated them.

The names between Zerubbabel and Zadok - Abiud, Eliakim, and Azor - are not known in any records dating from before the Gospel of Matthew, immediately leading many scholars, including Gundry, to believe that the author of Matthew simply made them up. In the eyes of such scholars, once the list moves away from the accepted genealogy of Jewish leaders it is fabricated until it reaches the known territory of Joseph's grandfather. The names listed are names that were frequent in the period of history, and so Gundry sees the author as having drawn the names from random parts of 1 Chronicles, disguising them to not make the copying obvious: According to Gundry

- The author of Matthew liked the meaning "son of Judah that lies behind the name Abihu, a priest, and modified it to become Abiud.

- The author then changed the name of Abihu's successor, Eliezer, into Eliakim to link him with the Eliakim of Isaiah 22 and also to link him with Jehoiakim (an identical name when theophory is taken into account)

- The third name comes from another significant priest - Azariah - which the author shortened to Azor.

- Achim is an abbreviation by the author of the name of Zadok's son, Achimaas

- Eliezer, another figure from 1 Chronicles, is turned into Eliud.

Women

By mentioning five women — Tamar, Ruth, Rahab, Bathsheba and Mary — Matthew's genealogy is unusual compared to those of the time, where women were not generally included at all; for example, the genealogy of Luke does not mention them. Albright and Mann support the theory that these women are mentioned to highlight the important roles women have played in the past, to imply that the other woman mentioned in the genealogy — Mary — is the equal of these. Feminist scholars such as A. J. Levine hold the idea that the presence of women in the genealogy serves to undermine the patriarchal message of a long list of males, while Brown feels that the presence of women is to deliberately show that God's action is not always in keeping with the moral politics of the time.

Tamar deceived and had sex with her father-in-law when he failed to provide proper support for her after she was widowed, Rahab was a prostitute, Ruth was a foreigner, and Bathsheba was seduced into adultery by David: all of those women who were either despised or abused by their contemporaries or who didn't conform to their society's expectations of virtue. Greater, more notable and virtuous women are not mentioned, leading Jerome to suggest that Matthew had included these women to illustrate how pressingly moral reform was needed, while Gundry sees them as an attempt to justify Jesus' undignified origin by showing that great leaders of the past had also been born to women of a dubious nature. Rahab was a Canaanite, and Tamar was likely a Canaanite, Ruth was a Moabite and Bathsheba was married to a Hittite and conceivably was one herself. According to John Chrysostom, the first to remark on their foreignness, their inclusion was a device to imply that Jesus was to be a saviour not only of the Jews, but also of the Gentiles.

Terminology

The phrase "book of the genealogy" or biblos geneseos has several possible meanings; most scholars agree that the most logical explanation is that this is simply toledot, although a small minority translate it more widely as "the book of coming" and thus consider it to refer to the entire Gospel. Brown stretches the grammar considerably to make it read "the book of the genesis brought about by Jesus", implying that it discusses the recreation of the world by Jesus.

According to Brown some have theorized that David's name precedes that of Abraham since the author of Matthew is trying to emphasize Jesus' Davidic ancestry. Gundry states that the structure of this passage attempts to portray Jesus as the culmination of the Old Testament genealogies.

Spelling

The author of Matthew has a tendency to use spellings of names that correspond to the spellings in the Septuagint rather than the Masoretic text, suggesting that the Septuagint formed the source for the genealogy. However, Rahab's name is spelt as Rachab, a departure from the Septuagint spelling Raab, though the spelling Rachab also appears in the works of Josephus, leading to speculation that this is a symptom of a change in pronunciation during this period. Additionally, Rahab's position is also peculiar, as all other traditions place her as the wife of Joshua not of Salmon.

The author of Matthew adds a "φ" to Asa's name. Gundry believes this is an attempt to make a connection with Psalm 78, which contains messianic prophecies, Asaph being the name to which Psalm 78 is attributed. However, most other scholars feel this is more likely a scribal error than a scheme, and most modern translators of the Bible "correct" Matthew in this verse. Whether it were the author of Matthew, or a later copyist, that would have made the error, is uncertain.

Amon has a similar feature. Matthew actually has Amos, rather than Amon, which Grundy has argued might have been an attempt to link to the minor prophet Amos, who made messianic predictions, but once again, other scholars feel this is most likely simply a typographical error.

Forty-two

The author of Matthew emphasizes that the names have been grouped into sets of 14, pointing out that "all the generations from Abraham to David are fourteen generations; and from David to the deportation to Babylon, fourteen generations; and from the deportation to Babylon to the Messiah, fourteen generations" (Mt. 1:17). The number 14 is itself important; not only is it twice 7, a holy number at the time, 14 is also the gematria of David. The division makes the birth of Jesus an important event by being the final one of the last set of 14. Calculations based on this division into 14s led Joachim of Fiore to predict that the Second Coming would occur in the thirteenth century.

There is a significant complication with this division - there are only 41 names listed in the direct line (including Jesus), not 42 (14x3), either leaving one of the divisions a member short, or implying that Jesus would have a son who, rather than Jesus, is to be the Messiah. A number of explanations have been advanced to account for this numerical feature. One is that the Matthew 1:17 [19] list 14 generations from Abraham to David (Inclusive of both Abraham and David), 14 generations from David to the exile (Inclusive of David and Josiah) and 14 from the exile to Jesus (inclusive of Jeconiah and Jesus) Thus, David's generation is counted twice.

The explanation supported by most scholars today is that Jeconiah has been confused with an individual of a similar name. Almost all other sources report that a king named Jehoiakim lay between Josiah and Jeconiah, and since the second theophory in the name Jeconiah (the ..iah) is transposed to the middle of his name in the Book of Kings, as Jehoiachin, it is plausible that the author of Matthew or a later scribe confused Jehoiakim for Jehoiachin. This would also explain why the text identifies Josiah as Jeconiah's father rather than grandfather, and why Jeconiah, usually regarded as an only-child, is listed as having a number of brothers, a description elsewhere considered more appropriate for Jehoiakim.

Virgin birth

Matthew 1:16 breaks with the pattern preceding it; it is at pains to distance Joseph from Jesus' actual parentage and point out that Joseph did not beget Jesus, but was simply the husband of the woman who was his mother. In the original Greek, the word translated as whom is unambiguously feminine. The shift to the passive voice also symbolizes the Virgin Birth.

Matthew 1:16 has attracted considerable scholarly attention because unusually the ancient sources show several different versions of it. For example, the Codex Koridethi has:

- Jacob was the father of Joseph,

- to whom the betrothed virgin

- Mary bore Jesus, called the Christ

While the Old Syriac Sinaiticus has

- Jacob was the father of Joseph,

- to whom the virgin Mary was

- betrothed, was the father of Jesus

The first version represents the same pattern as that used in most modern translations - unlike the prior genealogy, its convoluted wording, shifting to the passive voice, is at pains to distance Joseph from the parentage of Jesus, to support a Virgin Birth. The other version states clearly that Joseph was actually the father of Jesus, and while it does appear to state Mary is a virgin, the word now translated virgin actually corresponds to the Greek word parthenekos, which translates literally more as maid. Some scholars see these latter versions as evidence against the doctrine of the Virgin Birth, while others postulate that the original text only had words of the form "and Joseph was the father of Jesus", following the pattern of the prior verses, which later scribes altered to clarify that this didn't amount to biological parentage.

Raymond Brown has proposed that these variants are not so much concerned with arguing for or against the Virgin Birth, but for the doctrine of perpetual virginity of Mary, which became prominent at the time the variants were created; both appear to be attempts to avoid making Joseph a husband to Mary, and hence to suppress the suggestion of sexual activity between them. Perhaps the most obvious issue of all surrounding this aspect of the genealogy is that if Joseph is no more than a step father to Jesus, the question arises as to why Matthew devoted the prior verses to his genealogy. At the time legal kinship was generally considered more important than biological descent, and thus by demonstrating that Joseph was a member of the House of David, even an adopted son would be legally considered part of the same dynasty.

Family of Jesus

The Desposyni (from Greek δεσπόσυνος (desposunos) "of or belonging to the master or lord") was a sacred name reserved only for Jesus' blood relatives. The closely related word δεσπότης (despotes), literally meaning despot, but more generally meaning a lord, master, or ship owner, is commonly used of God, human slave-masters, and of Jesus in the reading Luke 13:25 found in Papyrus 75, in Jude 1:4, and possibly in 2nd Peter 2:1. In Ebionite belief, the desposyni included his mother Mary, his father Joseph, his un-named sisters, and his brothers James the Just, Joses, Simon and Jude; in modern mainstream Christian belief, Mary is counted as a blood relative, Joseph as a foster father or step father and the rest as siblings (Protestant belief) or half-siblings or cousins (Orthodox and Catholic).

Islam position

The genealogy of Jesus in the Qur'an does not go through Joseph, since Islam believes that Jesus had no human father. So the genealogy of Jesus goes through Mary (Maryam) his mother. According to the Qur'an, Jesus descended from Mary[20] and Mary was the daughter of Imran.[21] Imran and his house are valued a lot in the Qur'an[22] and the third chapter of Qur'an named to them as Al-Imran or House of Imran. Also according to Qur'an 19:28 Mary named Sister of Aaron, and in some narrations it is told that it means that Mary is from Aaron descendants.[23] According to some Islamic narrations David was not from Judah but was from Levi and Aron[24] and Jesus was from David and was from Levi and Aaron.

See also

- Genealogies of Genesis

- Tree of Jesse - Christ's ancestry in art

Notes

- ↑ Jeremiah 23:5–6

- ↑ Howard W. Clarke (2003), p. 1

- ↑ David D. Kupp (1996), p.170

- ↑ Scott Gregory Brown (2005), p.87

- ↑ Graham N. Stanton (1989), p.67

- ↑ Markus Bockmuehl, Donald A. Hagner (2005), p. 191

- ↑ Matthew 1:2–16, Luke 3:21-38

- ↑ 1 Chronicles 3:11-12, Matthew 1:9

- ↑ See and compare Ezra 7:3 with 1st Chronicles 6:7-10 thus giving precedence to Matthew’s stylistic choices.

- ↑ 1 Chronicles 3:5

- ↑ Some sources date a "generation" to roughly 25 years per generation, however calculations involving some genealogies in the Book of Chronicles (and perhaps in the Gospel of Luke) seem to be closer to 23.8 years per generation. "The number twenty [years per generation] is only a very approximate round number and perhaps should be considerably higher. Kalimi lists proposals ranging from twenty to thirty years per generation. Kalimi himself chooses twenty-three or twenty-four." (Isaac Kalimi, “Die Abfassungszeit der Chronik: Forschungsstand und Perspectiven,” Zeitschrift Fuer Die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft (ZAW) Vol. 105 (Berlin 1993) p. 230, cited in R. W. Klein, Introduction to the Book of Chronicles, in The Harper Collins Study Bible: New revised standard edition. Edited by W. A. Meeks (London: Harper Collins 1993), p.25.)

- ↑ Eusebius Church History i. 7; vi. 31, letter to Aristides

- ↑ John Gill's comments on Heli being Mary's father

- ↑ Vermes, Geza "The Nativity: History and Legend". Penguin (2006) ISBN 0-14-102446-1

- ↑ Emmerich, Anne Catherine The Life of the Blessed Virgin Mary p. 21

- ↑ CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Genealogy of Christ

- ↑ John Gill's comments on Heli being Mary's father

- ↑ Second Difficulty in "Genealogy of Christ", Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Matthew 1:17

- ↑ Qur'an 3:45

- ↑ Qur'an 66:12

- ↑ Qur'an 3:33

- ↑ Al-Burhan fi Tafseer Al-Qur'an ,Third Volume, Page 709

- ↑ Behar al Anvar V:13 P:440, Tafseer Al-Qomi V:1 P:82, The story of Prophets of Jazayeri Page 331

References

- Albright, W.F. and C.S. Mann. "Matthew." The Anchor Bible Series. New York: Doubleday & Company, 1971.

- Brown, Raymond E. The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in Matthew and Luke. London: G. Chapman, 1977.

- Gundry, Robert H. Matthew a Commentary on his Literary and Theological Art. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1982.

- Jones, Alexander. The Gospel According to St. Matthew. London: Geoffrey Chapman, 1965.

- Levine, Amy-Jill. "Matthew." Women's Bible Commentary. Carol A. Newsom and Sharon H. Ringe, eds. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1998.

- Howard Clark Kee, part 3, The Cambridge Companion to the Bible, Cambridge University Press, 1997

- Howard W. Clarke, The Gospel of Matthew and Its Readers, Indiana University Press, 2003

- Graham N. Stanton, The Gospels and Jesus, Oxford University Press, 1989

- Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible, Palo Alto: Mayfield, 1985.

- David D. Kupp, Matthew's Emmanuel: Divine Presence and God's People in the First, Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 0521570077

- Scott Gregory Brown, Mark's Other Gospel: Rethinking Morton Smith's Controversial Discovery, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2005, ISBN 0889204616

- Markus Bockmuehl, Donald A. Hagner, The Written Gospel, Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 0521832853

External links

- Genealogy of Jesus at Complete-Bible-Genealogy.com

- Dueling Genealogies Why there are two different genealogies for Jesus.

- Multiple translations

- Information on the Michaelangelo frescoes

- Catholic Encyclopedia article

- The Baptism and the Genealogy of Jesus

- Bible Study Manual on Genealogy of Jesus