Geber

| Muslim scientist |

|

|---|---|

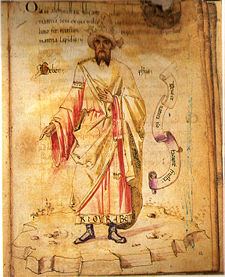

15th-century European portrait of "Geber", Codici Ashburnhamiani 1166, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence

|

|

| Name: | Jabir ibn Hayyan |

| Title: | Geber |

| Birth: | 721 AD |

| Death: | c. 815 AD |

| Maddhab: | Shī‘ah[1] Ja‘fari |

| Works: | Kitab al-Kimya, Kitab al-Sab'een, Book of the Kingdom, Book of the Balances , Book of Eastern Mercury, etc... |

| Influences: | Alchemy, Harbi al-Himyari, Ja'far al-Sadiq |

| Influenced: | Alchemy, Chemistry |

Abu Musa Jābir ibn Hayyān (Arabic: جابر ابن حيان) (c. 721–c. 815), known also by his Latinised name Geber, was a prominent Muslim polymath: a chemist and alchemist, astronomer and astrologer, engineer, geologist, philosopher, physicist, and pharmacist and physician. He is considered by many to be one of the fathers of chemistry".[2] His ethnic background is not clear;[3] although some sources state that he was an Arab,[4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18] other sources introduce him as Persian.[19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30]

The corpus of Jabir Ibn Hayyan is widely credited with the introduction of the experimental method in alchemy, and with the invention of numerous important processes still used in modern chemistry today, such as the syntheses of hydrochloric and nitric acids, distillation, and crystallisation. His original works are highly esoteric and probably coded, though nobody today knows what the code is. On the surface, his alchemical career revolved around an elaborate chemical numerology based on consonants in the Arabic names of substances and the concept of takwin, the artificial creation of life in the alchemical laboratory. Research has also established that oldest text of Jabiran corpus must have originated in the scientific culture of northeastern Persia.[31] This thesis is supported by the Persian language and Middle Persian terms used in the technical vocabulary.[32]

Contents |

Biography

Jabir was born in Tus, Khorasan, in Iran[33] , then ruled by the Umayyad Caliphate; the date of his birth is disputed, but most sources give 721 or 722. The information on his life and background is sketchy. In some sources, he is reported to have been the son of Hayyan al-Azdi, a pharmacist of the Arabian Azd tribe who emigrated from Yemen to Kufa (in present-day Iraq) during the Umayyad Caliphate.[34][18] Hayyan had supported the Abbasid revolt against the Umayyads, and was sent by them to the province of Khorasan (in present Iran) to gather support for their cause. He was eventually caught by the Ummayads and executed. His family fled back to Yemen,[35] where Jabir grew up and studied the Koran, mathematics and other subjects under a scholar named Harbi al-Himyari.[35] After the Abbasids took power, Jabir went back to Kufa, where he spent most of his career.

Jabir's father's profession may have contributed greatly to his interest in alchemy. In Kufa he became a student of the celebrated Islamic teacher and sixth Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq. He began his career practising medicine, under the patronage of the Barmakid Vizir of Caliph Haroun al-Rashid. It is known that in 776 he was engaged in alchemy in Kufa.

His connections to the Barmakid cost him dearly in the end. When that family fell from grace in 803, Jabir was placed under house arrest in Kufa, where he remained until his death. The date of his death is given as c.815 by the Encyclopædia Britannica, but as 808 by other sources.

The Geber Problem

Most or all of the Arabic corpus was written long after the time of Jabir ibn Hayyan. Paul Kruas' Jabir ibn Hayyan: Contribution a l'histoire des idees scientifiques dans l'Islam credits the Brethren of Purity with the entire Arabic corpus.Syed Haq offers evidence for possible 8th century origin of one text[36].

The Latin corpus of Pseudo-Geber was an original Latin work according to Berthelot. Holmyard argues for at least some Arabic origin but not 8th century. Newman shows a distant relationship to the Arabic work of Razi.[37]

Writings by Jabir

The Arabic corpus of Jabir Ibn Hayyan can be divided into four categories:

- The 112 Books dedicated to the Barmakids, viziers of Caliph Harun al-Rashid. This group includes the Arabic version of the Emerald Tablet, an ancient work that proved a recurring foundation of and source for alchemical operations. In the Middle Ages it was translated into Latin (Tabula Smaragdina) and widely diffused among European alchemists.

- The Seventy Books, most of which were translated into Latin during the Middle Ages. This group includes the Kitab al-Zuhra ("Book of Venus") and the Kitab Al-Ahjar ("Book of Stones").

- The Ten Books on Rectification, containing descriptions of "alchemists" such as Pythagoras, Socrates, Plato and Aristotle.

- The Books on Balance; this group includes his most famous 'Theory of the balance in Nature'.

In total, nearly 3,000 treatises and articles are credited to Jabir ibn Hayyan.[38] Following the pioneering work of Paul Kraus, who demonstrated that a corpus of some several hundred works ascribed to Jabir were probably a medley from different hands, mostly dating to the late ninth and early tenth centuries, many scholars believe that many of these works consist of commentaries and additions by his followers, particularly of a Shiite persuasion.[39]

The Latin corpus, dating from about 1310.

- Summa perfectionis magisterii ("The Height of the Perfection of Mastery"). [40]

- Liber fornacum ("Book of Stills"),

- De investigatione perfectionis ("On the Investigation of Perfection"), and

- De inventione veritatis ("On the Discovery of Truth").

- Testamentum gerberi

English Translations of Jabir

- E. J. Holmyard (ed.) The Arabic Works of Jabir ibn Hayyan, translated by Richard Russel in 1678. New York, E. P. Dutton (1928); Also Paris, P. Geuther.

- Syed Nomanul Haq, Names, Natures and Things: The Alchemists Jabir ibn Hayyan and his Kitab al-Ahjar (Book of Stones), [Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science p. 158] (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1994).

- Donald R. Hill, 'The Literature of Arabic Alchemy' in Religion: Learning and Science in the Abbasid Period, ed. by M.J.L. Young, J.D. Latham and R.B. Serjeant (Cambridge University Press, 1990) pp. 328-341, esp. pp 333-5.

- William Newman, New Light on the Identity of Geber, Sudhoffs Archiv, 1985, Vol.69, pp. 76-90.

- Geber and William Newman The Summa Perfectionis of Pseudo-Geber: A Critical Edition, Translation and Study ISBN 9004094664

Contributions

Chemistry

Jabir was taught chemistry by Imam Jafar Alsadiq a.s. Jaber is mostly renowned for his contributions to chemistry. He emphasised systematic experimentation,[41] and did much to free alchemy from superstition and turn it into a science.[42] He is credited with the invention of over twenty types of now-basic chemical laboratory equipment,[43] such as the alembic[44] and retort,[45] and with the discovery and description of many now-commonplace chemical substances and processes – such as the hydrochloric and nitric acids, distillation,[18] and crystallisation[2] – that have become the foundation of today's chemistry and chemical engineering.[18][46]

He also paved the way for most of the later Islamic alchemists, including al-Kindi, al-Razi, al-Tughrai and al-Iraqi, who lived in the 9th-13th centuries. His books strongly influenced the medieval European alchemists[46] and justified their search for the philosopher's stone.[47][48]

He clearly recognized and proclaimed the importance of experimentation. "The first essential in chemistry", he declared, "is that you should perform practical work and conduct experiments, for he who performs not practical work nor makes experiments will never attain the least degree of mastery."[41]

Jabir is also credited with the invention and development of a number of chemical substances and instruments that are still used today. He discovered sulfuric acid, and by distilling it together with various salts, Jabir discovered hydrochloric acid (from salt) and nitric acid (from saltpeter). By combining the two, he invented aqua regia, one of the few substances that can dissolve gold.[18] Besides its obvious applications to gold extraction and purification, this discovery would fuel the dreams and despair of alchemists for the next thousand years. He is also credited with the discovery of citric acid (the sour component of lemons and other unripe fruits),[2] acetic acid (from vinegar),[2][49] and tartaric acid (from wine-making residues).[2] Jabir also discovered and isolated several chemical elements, such as arsenic, antimony and bismuth.[43][50] He was also the first to classify sulfur (‘the stone which burns’ that characterized the principle of combustibility) and mercury (which contained the idealized principle of metallic properties) as 'elements'.[51] He was also the first to purify and isolate sulfur[52][51] and mercury[53][51] as pure elements.

Jabir applied his chemical knowledge to the improvement of many manufacturing processes, such as making steel and other metals, preventing rust, engraving gold, dyeing and waterproofing cloth, tanning leather, and the chemical analysis of pigments and other substances. He developed the use of manganese dioxide in glassmaking, to counteract the green tinge produced by iron — a process that is still used today. He noted that boiling wine released a flammable vapor, thus paving the way for the discovery of ethanol (alcohol) by Al-Kindi and Al-Razi.[54] According to Ismail al-Faruqi and Lois Lamya al-Faruqi, "In response to Jafar al-Sadik's wishes, [Jabir ibn Hayyan] invented a kind of paper that resisted fire, and an ink that could be read at night. He invented an additive which, when applied to an iron surface, inhabited rust and when applied to a textile, would make it water repellent."[55]

The seeds of the modern classification of elements into metals and non-metals could be seen in his chemical nomenclature. He proposed three categories:[56]

- "Spirits" which vaporise on heating, like arsenic (realgar, orpiment), camphor, mercury, sulfur, sal ammoniac, and ammonium chloride.

- "Metals", like gold, silver, lead, tin, copper, iron, and khar-sini;

- Non-malleable substances, that can be converted into powders, such as stones.

The origins of the idea of chemical equivalents can also be traced back to Jabir, who was the first to recognize that "a certain quantity of acid is necessary in order to neutralize a given amount of base." According to Jabir, the metals differ because of "different proportions of sulfur and mercury in them."[57]

In the Middle Ages, Jabir's treatises on alchemy were translated into Latin and became standard texts for European alchemists. These include the Kitab al-Kimya (titled Book of the Composition of Alchemy in Europe), translated by Robert of Chester (1144); and the Kitab al-Sab'een by Gerard of Cremona (before 1187). Marcelin Berthelot translated some of his books under the fanciful titles Book of the Kingdom, Book of the Balances, and Book of Eastern Mercury. Several technical Arabic terms introduced by Jabir, such as alkali, have found their way into various European languages and have become part of scientific vocabulary.

Alchemy

Jabir became an alchemist at the court of Caliph Harun al-Rashid, for whom he wrote the Kitab al-Zuhra ("The Book of Venus", on "the noble art of alchemy").

Jabir states in his Book of Stones (4:12) that "The purpose is to baffle and lead into error everyone except those whom God loves and provides for". His works seem to have been deliberately written in highly esoteric code (see steganography), so that only those who had been initiated into his alchemical school could understand them. It is therefore difficult at best for the modern reader to discern which aspects of Jabir's work are to be read as symbols (and what those symbols mean), and what is to be taken literally. Because his works rarely made overt sense, the term gibberish is believed to have originally referred to his writings (Hauck, p. 19).

Jabir's alchemical investigations ostensibly revolved around the ultimate goal of takwin — the artificial creation of life. The Book of Stones includes several recipes for creating creatures such as scorpions, snakes, and even humans in a laboratory environment, which are subject to the control of their creator. What Jabir meant by these recipes is today unknown.

Jabir's interest in alchemy was probably inspired by his teacher Ja'far al-Sadiq. Rumours of him being a Sufi is mostly fabricated for the main reason that no such school (i.e., Sufism) existed during that era of Islamic history. Ibn Hayyan was deeply religious, and repeatedly emphasizes in his works that alchemy is possible only by subjugating oneself completely to the will of Allah and becoming a literal instrument of Allah on Earth, since the manipulation of reality is possible only for Allah. The Book of Stones prescribes long and elaborate sequences of specific prayers that must be performed without error alone in the desert before one can even consider alchemical experimentation.

In his writings, Jabir pays tribute to Egyptian and Greek alchemists Hermes Trismegistus, Agathodaimon, Pythagoras, and Socrates. He emphasises the long history of alchemy, "whose origin is Arius ... the first man who applied the first experiment on the [philosopher's] stone... and he declares that man possesses the ability to imitate the workings of Nature" (Nasr, Seyyed Hussein, Science and Civilization of Islam).

Jabir's alchemical investigations were theoretically grounded in an elaborate numerology related to Pythagorean and Neoplatonic systems. The nature and properties of elements was defined through numeric values assigned the Arabic consonants present in their name, ultimately culminating in the number 17.

To Aristotelian physics, Jabir added the four properties of hotness, coldness, dryness, and moistness (Burkhardt, p. 29). Each Aristotelian element was characterised by these qualities: Fire was both hot and dry, earth cold and dry, water cold and moist, and air hot and moist. This came from the elementary qualities which are theoretical in nature plus substance. In metals two of these qualities were interior and two were exterior. For example, lead was cold and dry and gold was hot and moist. Thus, Jabir theorised, by rearranging the qualities of one metal, based on their sulfur/mercury content, a different metal would result. (Burckhardt, p. 29) This theory appears to have originated the search for al-iksir, the elusive elixir that would make this transformation possible — which in European alchemy became known as the philosopher's stone.

The elemental system used in medieval alchemy was developed by Jabir. His original system consisted of seven elements, which included the five classical elements found in the ancient Greek and Indian traditions (aether, air, earth, fire and water), in addition to two chemical elements representing the metals: sulphur, ‘the stone which burns’, which characterized the principle of combustibility, and mercury, which contained the idealized principle of metallic properties. Shortly thereafter, this evolved into eight elements, with the Arabic concept of the three metallic principles: sulphur giving flammability or combustion, mercury giving volatility and stability, and salt giving solidity.[51]

Jabir also made important contributions to medicine, astronomy/astrology, and other sciences. Only a few of his books have been edited and published, and fewer still are available in translation. The Geber crater, located on the Moon, is named after him.

Legacy

Max Meyerhoff states the following on Jabir ibn Hayyan: "His influence may be traced throughout the whole historic course of European alchemy and chemistry."[46]

The historian of chemistry Erick John Holmyard gives credit to Jabir for developing alchemy into an experimental science and he writes that Jabir's importance to the history of chemistry is equal to that of Robert Boyle and Antoine Lavoisier.[58]

The historian Paul Kraus, who had studied most of Jabir's extant works in Arabic and Latin, summarized the importance of Jabir ibn Hayyan to the history of chemistry by comparing his experimental and systematic works in chemistry with that of the allegorical and unintelligble works of the ancient Greek alchemists:[42]

“To form an idea of the historical place of Jabir’s alchemy and to tackle the problem of its sources, it is advisable to compare it with what remains to us of the alchemical literature in the Greek language. One knows in which miserable state this literature reached us. Collected by Byzantine scientists from the tenth century, the corpus of the Greek alchemists is a cluster of incoherent fragments, going back to all the times since the third century until the end of the Middle Ages.”

“The efforts of Berthelot and Ruelle to put a little order in this mass of literature led only to poor results, and the later researchers, among them in particular Mrs. Hammer-Jensen, Tannery, Lagercrantz , von Lippmann, Reitzenstein, Ruska, Bidez, Festugiere and others, could make clear only few points of detail…

The study of the Greek alchemists is not very encouraging. An even surface examination of the Greek texts shows that a very small part only was organized according to true experiments of laboratory: even the supposedly technical writings, in the state where we find them today, are unintelligible nonsense which refuses any interpretation.

It is different with Jabir’s alchemy. The relatively clear description of the processes and the alchemical apparatuses, the methodical classification of the substances, mark an experimental spirit which is extremely far away from the weird and odd esotericism of the Greek texts. The theory on which Jabir supports his operations is one of clearness and of an impressive unity. More than with the other Arab authors, one notes with him a balance between theoretical teaching and practical teaching, between the `ilm and the `amal. In vain one would seek in the Greek texts a work as systematic as that which is presented for example in the Book of Seventy.”

Popular culture

- The word gibberish is theorized to be derived from Jabir's name,[59] in reference to the incomprehensible technical jargon often used by alchemists, the most famous of whom was Jabir.[60] Other sources such as the Oxford English Dictionary suggest the term stems from gibber; however, the first known recorded use of the term "gibberish" was before the first known recorded use of the word "gibber" (see Gibberish).

- Geber is mentioned in Paulo Coelho's 1993 bestseller, The Alchemist.[61]

- There is a villain in the Japanese manga and anime series Bio Booster Armor Guyver by the name of Jearvill bun Hiyern (translated in various ways), who is most likely named after ibn Hayyan.

- Jabbir is said to be the creator of a (fictional) mystical chess set in Katherine Neville's novels The Eight and The Fire

Quote

- "My wealth let sons and brethren part. Some things they cannot share: my work well done, my noble heart — these are mine own to wear."[62]

See also

- Alchemy

- Alchemy and chemistry in medieval Islam

- Chemistry

- Al-Kindi

- List of Arab scientists and scholars

- List of Iranian scientists and scholars

- Muhammad ibn Zakariya ar-Razi

- Science in medieval Islam

References

- ↑ Henderson, Joseph L.; Dyane N. Sherwood (2003). Transformation of the Psyche: The Symbolic Alchemy of the Splendor Solis. East Sussex, UK: Psychology Press. pp. p. 11. ISBN 1-583-91950-3. http://books.google.com/books?id=NOcY_p6bz_0C&printsec=frontcover#PPA11,M1.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Derewenda, Zygmunt S. (2007), "On wine, chirality and crystallography", Acta Crystallographica Section A: Foundations of Crystallography 64: 246-258 [247]

- ↑ SN Nasr, "Life Sciences, Alchemy and Medicine", The Cambridge History of Iran, Cambridge, Volume 4, 1975, p. 412:"Jabir is entitled in the traditional sources as al-Azdi, al-Kufi, al-Tusi, al-Sufi. There is a debate as to whether he was an Arab from Kufa who lived in Khurasan or a Persian from Khorasan who later went to Kufa or whether he was, as some have suggested, of Syrian origin and later lived in Persia and Iraq"

- ↑ History of Analytical Chemistry By Ferenc Szabadváry,P 11,ISBN 2881245692.

- ↑ The Historical Background of Chemistry By Henry Marshall Leicester,P 63.

- ↑ Alchemy,Eric John Holmyard, P 68.

- ↑ Dragon's Brain Perfume an Historical Geography of Camphor, Robin Arthur Donkin, P 137.

- ↑ The Grand Contraption The World as Myth, Number, and Chance, David Allen Park, P 229.

- ↑ Cosmology in Gauge Field Theory and String Theory, By David Bailin, Alexander Love, P 181.

- ↑ The New Book of Knowledge, ISBN 0717205177, Page 446.

- ↑ The Biology of Alcoholism, By Benjamin Kissin, Henri Begleiter,P 576.

- ↑ Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine,By Thomas F. Glick, Steven John Livesey,Faith Wallis, ISBN 0415969301, P 280

- ↑ A History of Chemistry By Forris Jewett Moore, P 15.

- ↑ E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936 By M. Th. Houtsma, E. van Donzel, ISBN 9004082654, P 989.

- ↑ In Old Paris, by Robert W. Berger, P 164, ISBN 0934977666.

- ↑ Chemical Essays By Richard Watson, P 68

- ↑ Jabir, Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2007.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Ahmad Y Hassan, Arabic Alchemy

- ↑ A Dictionary of the History of Science by Anton Sebastian - p. 241

- ↑ The Alchemical Body By David Gordon - p. 366

- ↑ The Structure and Properties of Matter by Herman Thompson Briscoe - p. 10

- ↑ The Tincal Trail: A History of Borax by Edward John Cocks, Norman J. Travis - p. 4

- ↑ William Royall Newman, Gehennical Fire: The Lives of George Starkey, an American Alchemist in the Scientific Revolution, Harvard University Press, 1994. pg 94: "According to traditional bio-bibliography of Muslims, Jabir ibn Hayyan was a Persian alchemist who lived at some time in the eight century and wrote a wealth of books on virtually every aspect of natural philosophy"

- ↑ William R. Newman, The Occult and Manifest Among the Alchemist", in F. J. Ragep, Sally P Ragep, Steven John Livesey, "Tradition, Transmission, Transformation: Proceedings of Two Conferences on pre-Modern science held at University of Oklahoma", Brill,1996/1997, pg 178:"This language of extracting the hidden nature formed an important lemma for the extensive corpus associated with the Persian alchemist Jabir ibn Hayyan"

- ↑ Henry Corbin, "The Voyage and the Messenger: Iran and Philosophy", Translated by Joseph H. Rowe,North Atlantic Books, 1998. pg 45: "The Nisba al-Azdin certainly does not necessarily indicate Arab origin. Jabir seems to have been a client of the Azd tribe established in Kufa

- ↑ Tamara M. Green, "The City of the Moon God: Religious Traditions of Harran (Religions in the Graeco-Roman World) ", Brill, 1992. pg 177: "His most famous student was the Persian Jabir ibn Hayyan (b. circa 721 C.E.), under whose name the vast corpus of alchemical writing circulated in the medieval period in both the east and west, although many of the works attributed to Jabir have been demonstrated to be likely product of later Ismaili' tradition."

- ↑ David Gordon White, "The Alchemical Body: Siddha Traditions in Medieval India", University of Chicago Press, 1996. pg 447

- ↑ William R. Newman, Promethean Ambitions: Alchemy and the Quest to Perfect Nature, University of Chicago Press, 2004. pg 181: "The corpus ascribed to the eight-century Persian sage Jabir ibn Hayyan.."

- ↑ Wilbur Applebaum, The Scientific revolution and the foundation of modern science, Greenwood Press, 1995. pg 44: "The chief source of Arabic alchemy was associated with the name, in its Latinized form, of Geber, an eighth-century Persian. "

- ↑ Neil Kamil,Fortress of the Soul: Violence, Metaphysics, and Material Life in the Huguenots New World, 1517-1751 (Early America: History, Context, Culture), JHU Press, 2005. pg 182: "The ninth-century Persian alchemist Jabir ibn Hay- yan, also known as Geber, is accurately called pseudo-Geber since most of the works published under this name in the West were forgeries"

- ↑ Henry Corbin, "The Voyage and the Messenger: Iran and Philosophy", Translated by Joseph H. Rowe,North Atlantic Books, 1998. pg 46:This thesis is supposed by the Pahlavi and Persian terms used in the technical vocabulary.

- ↑ Henry Corbin, "The Voyage and the Messenger: Iran and Philosophy", Translated by Joseph H. Rowe,North Atlantic Books, 1998. pg 46:This thesis is supposed by the Pahlavi and Persian terms used in the technical vocabulary.

- ↑ ""Abu Musa Jabir ibn Hayyan"". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved on 2008-02-11.

- ↑ Holmyard, E.J.; Russell, R. (1997). The Works of Geber. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-0015-4.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 E. J. Holmyard (ed.) The Arabic Works of Jabir ibn Hayyan, translated by Richard Russell in 1678. New York, E. P. Dutton (1928); Also Paris, P. Geuther.

- ↑ Haq, Syed Nomanul; Jabir ibn Hayyan (1994). Names, Natures and Things: Jabir ibn Hayyan and His Kitab Al-Ahjar (Book of Stones). Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 0792325877.

- ↑ Geber; William R Newman (1991). The Summa Prefectionis of Pseudo-Geber: A Critical Edition, Translation and Study. Brill. ISBN 9004094644.

- ↑ Josef W. Meri, Jere L. Bacharach (2006), Medieval Islamic Civilization, Taylor and Francis, p. 25, ISBN 0415966914

- ↑ Paul Kraus, Jabir ibn Hayyan: Contribution à l'histoire des idées scientifiques dans l'Islam, cited Robert Irwin, 'The long siesta' in Times Literary Supllement, 25/1/2008 p.8

- ↑ William R. Newman, The Summa Perfectionis of Pseudo-Geber. A Critical Edition, Translation and Study, Leyde : E. J. Brill, 1991 (Collection de travaux de l'Académie Internationale d'Histoire des Sciences, 35).

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Koningsveld, Ronald; Stockmayer, Walter H. (2001), Polymer Phase Diagrams: A Textbook, Oxford University Press, pp. xii-xiii, ISBN 0198556349

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Kraus, Paul, Jâbir ibn Hayyân, Contribution à l'histoire des idées scientifiques dans l'Islam. I. Le corpus des écrits jâbiriens. II. Jâbir et la science grecque,. Cairo (1942-1943). Repr. By Fuat Sezgin, (Natural Sciences in Islam. 67-68), Frankfurt. 2002 (cf. Ahmad Y Hassan. "A Critical Reassessment of the Geber Problem: Part Three". Retrieved on 2008-08-09.)

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Ansari, Farzana Latif; Qureshi, Rumana; Qureshi, Masood Latif (1998), Electrocyclic reactions: from fundamentals to research, Wiley-VCH, p. 2, ISBN 3527297553

- ↑ Will Durant (1980). The Age of Faith (The Story of Civilization, Volume 4), p. 162-186. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671012002.

- ↑ Distillation, Hutchinson Encyclopedia, 2007.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Ḥusain, Muẓaffar. Islam's Contribution to Science. Page 94.

- ↑ Ragai, Jehane (1992), "The Philosopher's Stone: Alchemy and Chemistry", Journal of Comparative Poetics 12 (Metaphor and Allegory in the Middle Ages): 58-77

- ↑ Holmyard, E. J. (1924), "Maslama al-Majriti and the Rutbatu'l-Hakim", Isis 6 (3): 293-305

- ↑ Olga Pikovskaya, Repaying the West's Debt to Islam, BusinessWeek, March 29, 2005.

- ↑ Thomson, Thomas (1830), The History of Chemistry, Colburn and Bentley, pp. 129-30

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 Strathern, Paul. (2000). Mendeleyev’s Dream – the Quest for the Elements. New York: Berkley Books.

- ↑ Hassan, Ahmad Y. "Transfer Of Islamic Technology To The West, Part III: Technology Transfer in the Chemical Industries". History of Science and Technology in Islam. Retrieved on 2008-03-29.

- ↑ George Rafael, A is for Arabs, Salon.com, January 8, 2002

- ↑ Hassan, Ahmad Y. "Alcohol and the Distillation of Wine in Arabic Sources". History of Science and Technology in Islam. Retrieved on 2008-03-29.

- ↑ Ismail al-Faruqi and Lois Lamya al-Faruqi (1986), The Cultural Atlas of Islam, p. 328, New York

- ↑ Georges C. Anawati, "Arabic alchemy", in R. Rashed (1996), The Encyclopaedia of the History of Arabic Science, Vol. 3, p. 853-902 [866].

- ↑ Schufle, J. A.; Thomas, George (Winter 1971), "Equivalent Weights from Bergman's Data on Phlogiston Content of Metals", Isis 62 (4): 499-506 [500]

- ↑ Ahmad Y Hassan. "Arabic Alchemy". Retrieved on 2008-08-17.

- ↑ gibberish, Grose 1811 Dictionary

- ↑ Seaborg, Glenn T. (March 1980), "Our heritage of the elements", Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B (Springer Boston) 11 (1): 5-19

- ↑ Coelho, Paulo. The Alchemist. ISBN 006112416, p. 82.

- ↑ Holmyard, Eric John. Alchemy. Page 82

External links

- Britannica

- Encarta Encyclopedia

- Columbia Encyclopedia

- Chemical Heritage

- Article at Islam Online

- Article at Famous Muslims

- Article at Islam Online

- Article at Al Shindagah (includes an extract of Jabir's The Discovery of secrets)

- The Time of Jabir ibn Haiyan section from "History of Islamic Science"