Gauss's law

| Electromagnetism | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

Electricity · Magnetism

|

||||||||||||

In physics, Gauss's law, also known as Gauss's flux theorem, is a law relating the distribution of electric charge to the resulting electric field. It is one of the four Maxwell's equations, which form the basis of classical electrodynamics, and is also closely related to Coulomb's law. The law was formulated by Carl Friedrich Gauss in 1835, but was not published until 1867.

Gauss's law has two forms, an integral form and a differential form. They are related by the divergence theorem, also called "Gauss's theorem". Each of these forms can also be expressed two ways: In terms of a relation between the electric field E and the total electric charge, or in terms of the electric displacement field D and the free electric charge. (The former are given in sections 1 and 2, the latter in Section 3.)

Gauss's law has a close mathematical similarity with a number of laws in other areas of physics. See, for example, Gauss's law for magnetism and Gauss's law for gravity. In fact, any "inverse-square law" can be formulated in a way similar to Gauss's law: For example, Gauss's law itself is essentially equivalent to the inverse-square Coulomb's law, and Gauss's law for gravity is essentially equivalent to the inverse-square Newton's law of gravity. See the article Divergence theorem for more detail.

Gauss's law can be used to demonstrate that there is no electric field inside a Faraday cage with no electric charges. Gauss's law is something of an electrical analogue of Ampère's law, which deals with magnetism. Both equations were later integrated into Maxwell's equations.

Contents |

Integral form

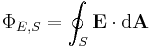

In its integral form (in SI units), the law states that, for any volume V in space, with surface S, the following equation holds:

where

E,S, called the "electric flux through S", is defined by

E,S, called the "electric flux through S", is defined by  , where

, where  is the electric field, and

is the electric field, and  is a differential area on the surface

is a differential area on the surface  with an outward facing surface normal defining its direction. (See surface integral for more details.) The surface S is the surface bounding the volume V.

with an outward facing surface normal defining its direction. (See surface integral for more details.) The surface S is the surface bounding the volume V. is the total electric charge in the volume V, including both free charge and bound charge (bound charge arises in the context of dielectric materials; see below).

is the total electric charge in the volume V, including both free charge and bound charge (bound charge arises in the context of dielectric materials; see below). is the electric constant, a fundamental physical constant.

is the electric constant, a fundamental physical constant.

Applying the integral form

If the electric field is known everywhere, Gauss's law makes it quite easy, in principle, to find the distribution of electric charge: The charge in any given region can be deduced by integrating the electric field to find the flux.

However, much more often, it is the reverse problem that needs to be solved: The electric charge distribution is known, and the electric field needs to be computed. This is much more difficult, since if you know the total flux through a given surface, that gives almost no information about the electric field, which (for all you know) could go in and out of the surface in arbitrarily complicated patterns.

An exception is if there is some symmetry in the situation, which mandates that the electric field passes through the surface in a uniform way. Then, if the total flux is known, the field itself can be deduced at every point. Common examples of symmetries which lend themselves to Gauss's law include cylindrical symmetry, planar symmetry, and spherical symmetry. See the article Gaussian surface for examples where these symmetries are exploited to compute electric fields.

Differential form

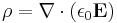

In differential form, Gauss's law states:

where:

denotes divergence,

denotes divergence,- E is the electric field,

is the total electric charge density (in units of C/m³), including both free and bound charge (see below).

is the total electric charge density (in units of C/m³), including both free and bound charge (see below). is the electric constant, a fundamental constant of nature.

is the electric constant, a fundamental constant of nature.

This is mathematically equivalent to the integral form, because of the divergence theorem.

Gauss's law in terms of free charge

Note on free charge versus bound charge

The electric charge that arises in the simplest textbook situations would be classified as "free charge"—for example, the charge which is transferred in static electricity, or the charge on a capacitor plate. In contrast, "bound charge" arises only in the context of dielectric (polarizable) materials. (All materials are polarizable to some extent.) When such materials are placed in an external electric field, the electrons remain bound to their respective atoms, but shift a microscopic distance in response to the field, so that they're more on one side of the atom than the other. All these microscopic displacements add up to give a macroscopic net charge distribution, and this constitutes the "bound charge".

Although microscopically, all charge is fundamentally the same, there are often practical reasons for wanting to treat bound charge differently from free charge. The result is that the more "fundamental" Gauss's law, in terms of E, is sometimes put into the equivalent form below, which is in terms of D and the free charge only. For a detailed definition of free charge and bound charge, and the proof that the two formulations are equivalent, see the "proof" section below.

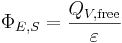

Integral form

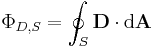

This formulation of Gauss's law states that, for any volume V in space, with surface S, the following equation holds:

where

is defined by

is defined by  , where

, where  is the electric displacement field, and the integration is a surface integral.

is the electric displacement field, and the integration is a surface integral. is the free electric charge in the volume V, not including bound charge (see below).

is the free electric charge in the volume V, not including bound charge (see below).

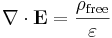

Differential form

The differential form of Gauss's law, involving free charge only, states:

where:

denotes divergence,

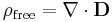

denotes divergence,- D is the electric displacement field (in units of C/m²), and *

is the free electric charge density (in units of C/m³), not including the bound charges in a material.

is the free electric charge density (in units of C/m³), not including the bound charges in a material.

The differential form and integral form are mathematically equivalent. The proof primarily involves the divergence theorem.

Proof of equivalence

-

Proof that the formulations of Gauss's law in terms of free charge are equivalent to the formulations involving total charge. In this proof, we will show that the equation is equivalent to the equation

Note that we're only dealing with the differential forms, not the integral forms, but that is sufficient since the differential and integral forms are equivalent in each case, by the divergence theorem.

We introduce the polarization density P, which has the following relation to E and D:

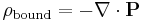

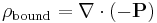

and the following relation to the bound charge:

Now, consider the three equations:

The key insight is that the sum of the first two equations is the third equation. This completes the proof: The first equation is true by definition, and therefore the second equation is true if and only if the third equation is true. So the second and third equations are equivalent, which is what we wanted to prove.

In linear materials

In homogeneous, isotropic, nondispersive, linear materials, there is a nice, simple relationship between E and D:

where  is the permittivity of the material. Under these circumstances, there is yet another pair of equivalent formulations of Gauss's law:

is the permittivity of the material. Under these circumstances, there is yet another pair of equivalent formulations of Gauss's law:

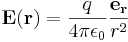

Relation to Coulomb's law

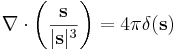

Deriving Gauss's law from Coulomb's law

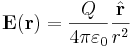

Gauss's law can be derived from Coulomb's law, which states that the electric field due to a stationary point charge is:

where

- er is the radial unit vector,

- r is the radius, |r|,

is the electric constant,

is the electric constant,- q is the charge of the particle, which is assumed to be located at the origin.

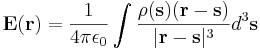

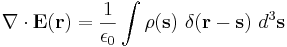

Using the expression from Coulomb's law, we get the total field at r by using an integral to sum the field at r due to the infinitesimal charge at each other point s in space, to give

where  is the charge density. If we take the divergence of both sides of this equation with respect to r, and use the known theorem[1]

is the charge density. If we take the divergence of both sides of this equation with respect to r, and use the known theorem[1]

where δ(s) is the Dirac delta function, the result is

Using the "sifting property" of the Dirac delta function, we arrive at

which is the differential form of Gauss's law, as desired.

Note that since Coulomb's law only applies to stationary charges, there is no reason to expect Gauss's law to hold for moving charges based on this derivation alone. In fact, Gauss's law does hold for moving charges, and in this respect Gauss's law is more general than Coulomb's law.

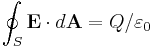

Deriving Coulomb's law from Gauss's law

Strictly speaking, Coulomb's law cannot be derived from Gauss's law alone, since Gauss's law does not give any information regarding the curl of E (see Helmholtz decomposition and Faraday's law). However, Coulomb's law can be proven from Gauss's law if it is assumed, in addition, that the electric field from a point charge is spherically-symmetric (this assumption, like Coulomb's law itself, is exactly true if the charge is stationary, and approximately true if the charge is in motion).

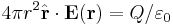

Taking S in the integral form of Gauss's law to be a spherical surface of radius r, centered at the point charge Q, we have

By the assumption of spherical symmetry, the integrand is a constant which can be taken out of the integral. The result is

where  is a unit vector pointing radially away from the charge. Again by spherical symmetry, E points in the radial direction, and so we get

is a unit vector pointing radially away from the charge. Again by spherical symmetry, E points in the radial direction, and so we get

which is essentially equivalent to Coulomb's law.

Thus the inverse-square law dependence of the electric field in Coulomb's law follows from Gauss's law.

See also

- Maxwell's equations

- Gaussian surface

- Carl Friedrich Gauss

- Divergence theorem

- Flux

- Method of image charges

References

Jackson, John David (1999). Classical Electrodynamics, 3rd ed., New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-30932-X.

External links

- MIT Video Lecture Series (30 x 50 minute lectures)- Electricity and Magnetism Taught by Professor Walter Lewin.

- section on Gauss's law in an online textbook

- MISN-0-132 Gauss's Law for Spherical Symmetry (PDF file) by Peter Signell for Project PHYSNET.

- MISN-0-133 Gauss's Law Applied to Cylindrical and Planar Charge Distributions (PDF file) by Peter Signell for Project PHYSNET.