Stomach cancer

| Stomach cancer Classification and external resources |

|

|

|

|---|---|

| A suspicious stomach ulcer that was diagnosed as cancer on biopsy and resected. Surgical specimen. | |

| ICD-10 | C16. |

| ICD-9 | 151 |

| OMIM | 137215 |

| DiseasesDB | 12445 |

| eMedicine | med/845 |

| MeSH | D013274 |

Stomach or gastric cancer can develop in any part of the stomach and may spread throughout the stomach and to other organs; particularly the esophagus and the small intestine. Stomach cancer causes nearly one million deaths worldwide per year.[1]

Contents |

Epidemiology

Stomach cancer is the fourth most common cancer worldwide with 930,000 cases diagnosed in 2002.[2] It is a disease with a high death rate (700,000 per year) making it the second most common cause of cancer death worldwide after lung cancer.[3]

It represents roughly 2% (25,500 cases) of all new cancer cases yearly in the United States, but it is much more common in Korea, Japan, Great Britain, South America, and Iceland. It is associated with high salt in the diet, smoking, and low intake of fruits and vegetables. Infection with the bacterium H. pylori is the main risk factor in about 80% or more of gastric cancers. It is more common in men.

Gastric cancer has very high incidence in Korea and Japan. Gastric cancer is the leading cancer type in Korea with 20.8% of malignant neoplasms, the second leading cause of cancer deaths. It is suspected several risk factors are involved including diet, gastritis, intestinal metaplasia and Helicobacter pylori infection. A Korean diet, high in salted, stewed and broiled foods, is thought to be a contributing factor. Ten percent of cases show a genetic component.[4] In Japan and other countries bracken consumption and spores are correlated to stomach cancer incidence.[5] Epidemiologists have yet to fully account for the high rates of gastric cancer as compared to other countries. Gastric cancer shows a male predominance in its incidence as up to 3 males are affected for every female. Estrogen may protect women against the development of this cancer form.[6]

A very small percentage of diffuse-type gastric cancers (see Histopathology below) are thought to be genetic. Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer (HDGC) has recently been identified and research is ongoing. However, genetic testing and treatment options are already available for families at risk.[7]

Metastasis occurs in 80-90% of individuals with stomach cancer, with a five year survival rate of 75% in those diagnosed in early stages and less than 30% of those diagnosed in late stages.

Symptoms

Stomach cancer is often asymptomatic or causes only nonspecific symptoms in its early stages. By the time symptoms occur, the cancer has generally metastasized to other parts of the body, one of the main reasons for its poor prognosis. Stomach cancer can cause the following signs and symptoms:

Early

- Indigestion or a burning sensation (heartburn)

- Loss of appetite, especially for meat

Late

- Abdominal pain or discomfort in the upper abdomen

- Nausea and vomiting

- Diarrhea or constipation

- Bloating of the stomach after meals

- Weight loss

- Weakness and fatigue

- Bleeding (vomiting blood or having blood in the stool), which can lead to anemia

- Dysphagia; this feature suggests a tumor in the cardia or extension of the gastric tumor in to the Oesopagus.

These can be symptoms of other problems such as a stomach virus, gastric ulcer or tropical sprue and diagnosis should be done by a gastroenterologist or an oncologist.

Diagnosis

To find the cause of symptoms, the doctor asks about the patient's medical history, does a physical exam, and may order laboratory studies. The patient may also have one or all of the following exams:

- Gastroscopic exam is the diagnostic method of choice. This involves insertion of a fibre optic camera into the stomach to visualize it.

- Upper GI series (may be called barium roentgenogram)

- Computed tomography or CT scanning of the abdomen may reveal gastric cancer, but is more useful to determine invasion into adjacent tissues, or the presence of spread to local lymph nodes.

Abnormal tissue seen in a gastroscope examination will be biopsied by the surgeon or gastroenterologist. This tissue is then sent to a pathologist for histological examination under a microscope to check for the presence of cancerous cells. A biopsy, with subsequent histological analysis, is the only sure way to confirm the presence of cancer cells.

Various gastroscopic modalities have been developed to increased yield of detect mucosa with a dye that accentuates the cell structure and can identify areas of dysplasia. Endocytoscopy involves ultra-high magnification to visualize cellular structure to better determine areas of dysplasia. Other gastroscopic modalities such as optical coherence tomography are also being tested investigationally for similar applications.[8]

A number of cutaneous conditions are associated with gastric cancer. A condition of darkened hyperplasia of the skin, frequently of the axilla and groin, known as acanthosis nigricans, is associated with intra-abdominal cancers such as gastric cancer. Other cutaneous manifestations of gastric cancer include tripe palms (a similar darkening hyperplasia of the skin of the palms) and the sign of Leser-Trelat, which is the rapid development of skin lesions known as seborrheic keratoses.[9]

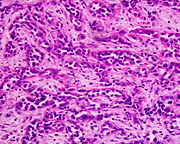

Histopathology

- Gastric adenocarcinoma is a malignant epithelial tumor, originating from glandular epithelium of the gastric mucosa. It invades the gastric wall, infiltrating the muscularis mucosae, the submucosa and thence the muscularis propria. Histologically, there are two major types of gastric cancer (Lauren classification): intestinal type and diffuse type.

- Intestinal type adenocarcinoma: tumor cells describe irregular tubular structures, harboring pluristratification, multiple lumens, reduced stroma ("back to back" aspect). Often, it associates intestinal metaplasia in neighboring mucosa. Depending on glandular architecture, cellular pleomorphism and mucosecretion, adenocarcinoma may present 3 degrees of differentiation: well, moderate and poorly differentiate.

- Diffuse type adenocarcinoma (mucinous, colloid): Tumor cells are discohesive and secrete mucus which is delivered in the interstitium producing large pools of mucus/colloid (optically "empty" spaces). It is poorly differentiated. If the mucus remains inside the tumor cell, it pushes the nucleus at the periphery - "signet-ring cell".

Staging

If cancer cells are found in the tissue sample, the next step is to stage, or find out the extent of the disease. Various tests determine whether the cancer has spread and, if so, what parts of the body are affected. Because stomach cancer can spread to the liver, the pancreas, and other organs near the stomach as well as to the lungs, the doctor may order a CT scan, a PET scan, an endoscopic ultrasound exam, or other tests to check these areas. Blood tests for tumor markers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen (CA) may be ordered, as their levels correlate to extent of metastasis, especially to the liver, and the cure rate.

Staging may not be complete until after surgery. The surgeon removes nearby lymph nodes and possibly samples of tissue from other areas in the abdomen for examination by a pathologist.

TNM staging is used

Treatment

Like any cancer, treatment is adapted to fit each person's individual needs and depends on the size, location, and extent of the tumor, the stage of the disease, and general health. Cancer of the stomach is difficult to cure unless it is found in an early stage (before it has begun to spread). Unfortunately, because early stomach cancer causes few symptoms, the disease is usually advanced when the diagnosis is made. Treatment for stomach cancer may include surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy. New treatment approaches such as biological therapy and improved ways of using current methods are being studied in clinical trials.

Surgery

Surgery is the most common treatment for stomach cancer. The surgeon removes part or all of the stomach, as well as some of the tissue around the stomach, with the basic goal of removing all cancer and a margin of normal tissue. Depending on the extent of invasion and the location of the tumor, surgery may also include removal of part of the intestine or pancreas . Tumors in the lower parts of the stomach may call for a Billroth I or Billroth II procedure. Endoscopic mucosal resection is a treatment for early gastric cancer that has been pioneered in Japan, but is available in the United States at some centers. In this procedure, the tumor is removed from the wall of the stomach using an endoscope, with the advantage in that it is a smaller operation than removing the stomach. Surgical interventions are currently curative in less than 40% of cases, and, in cases of metastasis, may only be palliative.

Chemotherapy

The use of chemotherapy to treat stomach cancer has no established standard of care. Unfortunately, stomach cancer has not been especially sensitive to these drugs until recently, and historically served to palliatively reduce the size of the tumor and increase survival time. Some drugs used in stomach cancer treatment include: 5-FU (fluorouracil), BCNU (carmustine), methyl-CCNU (Semustine), and doxorubicin (Adriamycin), as well as Mitomycin C, and more recently cisplatin and taxotere in various combinations. The relative benefits of these drugs, alone and in combination, are unclear.[10] Scientists are exploring the benefits of giving chemotherapy before surgery to shrink the tumor, or as adjuvant therapy after surgery to destroy remaining cancer cells. Combination treatment with chemotherapy and radiation therapy is also under study. Doctors are testing a treatment in which anticancer drugs are put directly into the abdomen (intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemoperfusion). Chemotherapy also is being studied as a treatment for cancer that has spread, and as a way to relieve symptoms of the disease. The side effects of chemotherapy depend mainly on the drugs the patient receives.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy (also called radiotherapy) is the use of high-energy rays to damage cancer cells and stop them from growing. When used, it is generally in combination with surgery and chemotherapy, or used only with chemotherapy in cases where the individual is unable to undergo surgery. Radiation therapy may be used to relieve pain or blockage by shrinking the tumor for palliation of incurable disease

Multimodality therapy

While previous studies of multimodality therapy (combinations of surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy) gave mixed results, the Intergroup 0116 (SWOG 9008) study[11] showed a survival benefit to the combination of chemotherapy and radiation therapy in patients with nonmetastatic, completely resected gastric cancer. Patients were randomized after surgery to the standard group of observation alone, or the study arm of combination chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Those in the study arm receiving chemotherapy and radiation therapy survived on average 36 months, compared to 27 months with observation.

References

- ↑ "Cancer". World Health Organization (February 2006). Retrieved on 2007-05-24.

- ↑ Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:74-108

- ↑ Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:74-108.

- ↑ AHyuk-Joon Lee, Han-Kwang Yang, Yoon-Ok Ahn, Gastric cancer in Korea Gastric Cancer, Volume 5, Number 3 / September, 2002. DOI:10.1007/s101200200031]

- ↑ Alonso-Amelot ME, Avendano M., Human Carcinogenesis and Bracken Fern: A Review of the Evidence, Curr Med Chem. 2002 Mar;9(6):675-86

- ↑ Estrogen in the development of esophageal and gastric adenocarcinoma (Thesis) http://diss.kib.ki.se/2007/978-91-7357-370-2/

- ↑ Brooks-Wilson AR, Kaurah P, Suriano G, et al (2004). "Germline E-cadherin mutations in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: assessment of 42 new families and review of genetic screening criteria". J. Med. Genet. 41 (7): 508–17. doi:. PMID 15235021.

- ↑ Inoue H, Kudo SE, Shiokawa A (January 2005). "Technology insight: Laser-scanning confocal microscopy and endocytoscopy for cellular observation of the gastrointestinal tract". Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2 (1): 31–7. doi:. PMID 16265098.

- ↑ Pentenero M, Carrozzo M, Pagano M, Gandolfo S (July 2004). "Oral acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms and sign of leser-trélat in a patient with gastric adenocarcinoma". Int. J. Dermatol. 43 (7): 530–2. doi:. PMID 15230897.

- ↑ Scartozzi M, Galizia E, Verdecchia L, et al (April 2007). "Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer: across the years for a standard of care". Expert Opin Pharmacother 8 (6): 797–808. doi:. PMID 17425475. http://www.expertopin.com/doi/abs/10.1517/14656566.8.6.797.

- ↑ Macdonald JS, Smalley SR, Benedetti J, et al (2001). "Chemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction". N. Engl. J. Med. 345 (10): 725–30. doi:. PMID 11547741.

External links

- National Cancer Institute Gastric cancer treatment guidelines

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||