Gas

- This page is about the physical properties of gas as a state of matter. For the uses of gases, and other meanings, see Gas (disambiguation).

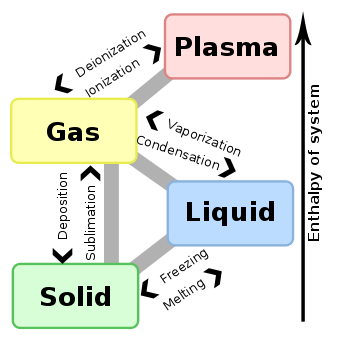

In physics, a gas is a state of matter, consisting of a collection of particles (molecules, atoms, ions, electrons, etc.) without a definite shape or volume that are in more or less random motion.

Contents |

Physical characteristics

Due to the electronic nature of the aforementioned particles, a "force field" is present throughout the space around them. Interactions between these "force fields" from one particle to the next give rise to the term intermolecular forces. Dependent on distance, these intermolecular forces influence the motion of these particles and hence their thermodynamic properties. At the temperatures and pressures characteristic of many applications, these particles are normally greatly separated. This separation corresponds to a very weak attractive force. As a result, for many applications, this intermolecular force becomes negligible.

A gas also exhibits the following characteristics:

- Relatively low density and viscosity compared to the solid and liquid states of matter.

- Will expand and contract greatly with changes in temperature or pressure, thus the term "compressible".

- Will diffuse readily, spreading apart in order to homogeneously distribute itself throughout any container.

Macroscopic

When analyzing a system, it is typical to specify a length scale. A larger length scale may correspond to a macroscopic view of the system, while a smaller length scale corresponds to a microscopic view.

On a macroscopic scale, the quantities measured are in terms of the large scale effects that a gas has on a system or its surroundings such as its velocity, pressure, or temperature. Mathematical equations, such as the Extended hydrodynamic equations, Navier-Stokes equations and the Euler equations have been developed to attempt to model the relations of the pressure, density, temperature, and velocity of a moving gas.

Pressure

The pressure exerted by a gas uniformly across the surface of a container can be described by simple kinetic theory. The particles of a gas are constantly moving in random directions and frequently collide with the walls of the container and/or each other. These particles all exhibit the physical properties of mass, momentum, and energy, which all must be conserved. In classical mechanics, Momentum, by definition, is the product of mass and velocity. Kinetic energy is one half the mass multiplied by the square of the velocity.

The sum of all the normal components of force exerted by the particles impacting the walls of the container divided by the area of the wall is defined to be the pressure. The pressure can then be said to be the average linear momentum of these moving particles. A common misconception is that the collisions of the molecules with each other is essential to explain gas pressure, but in fact their random velocities are sufficient to define this quantity.

Temperature

The temperature of any physical system is the result of the motions of the molecules and atoms which make up the system. In statistical mechanics, temperature is the measure of the average kinetic energy stored in a particle. The methods of storing this energy are dictated by the degrees of freedom of the particle itself (energy modes). These particles have a range of different velocities, and the velocity of any single particle constantly changes due to collisions with other particles. The range in speed is usually described by the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution.

Specific Volume

When performing a thermodynamic analysis, it is typical to speak of intensive and extensive properties. Properties which depend on the amount of gas are called extensive properties, while properties that do not depend on the amount of gas are called intensive properties. Specific volume is an example of an intensive property because it is the volume occupied by a unit of mass of a material, meaning the volume has been divided through by the mass in order to obtain a quantity in terms of, for example, . Notice that the difference between volume and specific volume differ in that the specific quantity is mass independent.

. Notice that the difference between volume and specific volume differ in that the specific quantity is mass independent.

Density

Because the molecules are free to move about in a gas, the mass of the gas is normally characterized by its density. Density is the mass per volume of a substance or simply, the inverse of specific volume. For gases, the density can vary over a wide range because the molecules are free to move. Macroscopically, density is a state variable of a gas and the change in density during any process is governed by the laws of thermodynamics. Given that there are many particles in completely random motion, for a static gas, the density is the same throughout the entire container. Density is therefore a scalar quantity; it is a simple physical quantity that has a magnitude but no direction associated with it. It can be shown by kinetic theory that the density is proportional to the size of the container in which a fixed mass of gas is confined.

Microscopic

On the microscopic scale, the quantities measured are at the molecular level. Different theories and mathematical models have been created to describe molecular or particle motion. A few of the gas-related models are listed below.

Kinetic theory

Kinetic theory attempts to explain macroscopic properties of gases by considering their molecular composition and motion.

Brownian motion

Brownian motion is the mathematical model used to describe the random movement of particles suspended in a fluid often called particle theory.

Since it is at the limit of (or beyond) current technology to observe individual gas particles (atoms or molecules), only theoretical calculations give suggestions as to how they move, but their motion is different from Brownian Motion. The reason is that Brownian Motion involves a smooth drag due to the frictional force of many gas molecules, punctuated by violent collisions of an individual (or several) gas molecule(s) with the particle. The particle (generally consisting of millions or billions of atoms) thus moves in a jagged course, yet not so jagged as would be expected if an individual gas molecule was examined.

Intermolecular forces

As discussed earlier, momentary attractions (or repulsions) between particles have an effect on gas dynamics. In physical chemistry, the name given to these intermolecular forces is van der Waals force.

Simplified models

An equation of state (for gases) is a mathematical model used to roughly describe or predict the state of a gas. At present, there is no single equation of state that accurately predicts the properties of all gases under all conditions. Therefore, a number of much more accurate equations of state have been developed for gases under a given set of assumptions. The "gas models" that are most widely discussed are "Real Gas", "Ideal Gas" and "Perfect Gas". Each of these models have their own set of assumptions to facilitate the analysis of a given thermodynamic system.

Real gas

Real gas effects refers to an assumption base where the following are taken into account:

- Compressibility effects

- Variable heat capacity

- Van der Waals forces

- Non-equilibrium thermodynamic effects

- Issues with molecular dissociation and elementary reactions with variable composition.

For most applications, such a detailed analysis is excessive. An example where "Real Gas effects" would have a significant impact would be on the Space Shuttle re-entry where extremely high temperatures and pressures are present.

Ideal gas

An "ideal gas" is a simplified "real gas" with the assumption that the compressibility factor  is set to 1. So the state variables follow the ideal gas law.

is set to 1. So the state variables follow the ideal gas law.

This approximation is more suitable for applications in engineering although simpler models can be used to produce a "ball-park" range as to where the real solution should lie. An example where the "ideal gas approximation" would be suitable would be inside a combustion chamber of a jet engine. It may also be useful to keep the elementary reactions and chemical dissociations for calculating emissions.

Perfect gas

By definition, A perfect gas is one in which intermolecular forces are neglected. So, along with the assumptions of an Ideal Gas, the following assumptions are added:

- Neglected intermolecular forces

By neglecting these forces, the equation of state for a perfect gas can be simply derived from kinetic theory or statistical mechanics.

This type of assumption is useful for making calculations very simple and easy to do. With this assumption, the Ideal gas law can be applied without restriction and many complications that may arise from the Van der Waals forces can be neglected.

Along with the definition of a perfect gas, there are also two more simplifications that can be made although various textbooks either omit or combine the following simplifications into a general "perfect gas" definition. For sake of clarity, these simplifications are defined separately.

Thermally perfect

- The gas is in Thermodynamic equilibrium

- Not chemically reacting

- Internal energy, Enthalpy, and Specific Heat are functions of Temperature only.

This type of approximation is useful for modeling, for example, an axial compressor where temperature fluctuations are usually not large enough to cause any significant deviations from the Thermally perfect gas model. Heat capacity is still allowed to vary, though only with temperature and molecules are not permitted to dissociate.

Calorically perfect

The Calorically perfect gas model is the most restrictive as it applies all the previous assumptions expressed in the Thermally perfect model and also adds:

- Constant Specific Heats

Although this may be the most restrictive model, it still may be accurate enough to make reasonable calculations. For example, if a model of one compression stage of the axial compressor mentioned in the previous example was made (one with variable  , and one with constant

, and one with constant  ) to compare the two simplifications, the deviation may be found at a small enough order of magnitude that other factors that come into play in this compression would have a greater impact on the final result than whether or not

) to compare the two simplifications, the deviation may be found at a small enough order of magnitude that other factors that come into play in this compression would have a greater impact on the final result than whether or not  was held constant. (compressor tip-clearance, boundary layer/frictional losses, manufacturing impurities, etc.)

was held constant. (compressor tip-clearance, boundary layer/frictional losses, manufacturing impurities, etc.)

Historical Synthesis

Boyle's Law was perhaps the first expression of an equation of state. In 1662 Robert Boyle, an Irishman, performed a series of experiments employing a J-shaped glass tube, which was sealed on one end. Mercury was added to the tube, trapping a fixed quantity of air in the short, sealed end of the tube. Then the volume of gas was carefully measured as additional mercury was added to the tube. The pressure of the gas could be determined by the difference between the mercury level in the short end of the tube and that in the long, open end. Through these experiments, Boyle noted that the gas volume varied inversely with the pressure. In mathematical form, this can be stated as:  .

.

This law is used widely to describe different thermodynamic processes by adjusting the equation to read  and then varying the

and then varying the  through different values such as the specific heat ratio, γ.

through different values such as the specific heat ratio, γ.

In 1787 the French physicist Jacques Charles found that oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and air expand to the same extent over the same 80 kelvin interval.

In 1802, Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac published results of similar experiments, indicating a linear relationship between volume and temperature:

In 1801 John Dalton published the Law of Partial Pressures: The pressure of a mixture of gases is equal to the sum of the pressures of all of the constituent gases alone. Mathematically, this can be represented for n species as:

Special Topics

Compressibility

The compressibility factor ( ) is used to alter the ideal gas equation to account for the real gas behavior. It is sometimes referred to as a "fudge-factor" to make the ideal gas law more accurate for the application. Usually this

) is used to alter the ideal gas equation to account for the real gas behavior. It is sometimes referred to as a "fudge-factor" to make the ideal gas law more accurate for the application. Usually this  value is very close to unity.

value is very close to unity.

Reynolds Number

In fluid mechanics, the Reynolds number is the ratio of inertial forces (vsρ) to viscous forces (μ/L). It is one of the most important dimensionless numbers in fluid dynamics and is used, usually along with other dimensionless numbers, to provide a criterion for determining dynamic similitude.

Viscosity

Pressure acts perpendicular (normal) to the wall. The tangential (shear) component of the force that is left over is related to the viscosity of the gas. As an object moves through a gas, viscous effects become more prevalent.

Turbulence

In fluid dynamics, turbulence or turbulent flow is a flow regime characterized by chaotic, stochastic property changes. This includes low momentum diffusion, high momentum convection, and rapid variation of pressure and velocity in space and time.

Boundary Layer

Particles will, in effect, "stick" to the surface of an object moving through it. This layer of particles is called the boundary layer. At the surface of the object, it is essentially static due to the friction of the surface. The object, with its boundary layer is effectively the new shape of the object that the rest of the molecules "see" as the object approaches. This boundary layer can separate from the surface, essentially creating a new surface and completely changing the flow path. The classical example of this is a stalling airfoil.

Maximum Entropy Principle

As the total number of degrees of freedom approaches infinity, the system will be found in the macrostate that corresponds to the highest multiplicity.

Thermodynamic Equilibrium

Equilibrium thermodynamics applies if the energy change within a system occurs on a timescale large enough for a sufficient number of molecular collisions to occur so that the energy transfer between molecules and between energy modes to allow the new energy value to be distributed in equilibrium among the molecules. (For typical systems, this is on the order of a few nanoseconds)

Etymology

The word "gas" was invented by Jan Baptist van Helmont, perhaps as a Dutch pronunciation re-spelling of "chaos".[1]

See also

References

- John D. Anderson. Modern Compressible Flow: Third Edition New York, NY : McGraw-Hill, 2004. ISBN 007-124136-1

- Philip Hill and Carl Peterson. Mechanics and Thermodynamics of Propulsion: Second Edition Addison-Wesley, 1992. ISBN 0-201-14659-2

- John D. Anderson. Fundamentals of Aerodynamics: Fourth Edition New York, NY : McGraw-Hill, 2007. ISBN-13: 978-0-07-295046-5 ISBN-10: 0-07-295046-3

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Animated Gas Lab. Accessed February, 2008.

- Georgia State University. HyperPhysics. Accessed February, 2008.

- Antony Lewis WordWeb. Accessed February, 2008.

- Northwestern Michigan College The Gaseous State. Accessed February, 2008.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||