Gadsden Purchase

The Gadsden Purchase (known as Venta de La Mesilla or Treaty of La Mesilla in Mexico[2]) is a 29,670-square-mile (76,800 km2) region of what is today southern Arizona and New Mexico that was purchased by the United States in a treaty signed by President Franklin Pierce on June 24, 1853, and then ratified by the U.S. Senate on April 25, 1854. It is named for James Gadsden, the American ambassador to Mexico at the time. The purchase included lands south of the Gila River and west of the Rio Grande. The Gadsden Purchase was intended to allow for the construction of a transcontinental railroad along a very southern route, and it was part of negotiations needed to finalize border issues that remained unresolved from the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, which had ended the Mexican-American War of 1846-48.

As the railroad age grew, business-oriented Southerners saw that a railroad linking the South with the Pacific Coast would expand trade opportunities. However, the topography of the southern portion of the Mexican Cession was too mountainous to allow a direct route, and what possible routes existed tended to run to the north at their eastern ends, which would favor connections with northern railroads. That would ultimately favor Northern seaports. Any practical route with a southeastern terminus, in order to avoid the mountains, would need to swing south into what was then Mexican territory.

The administration of Franklin Pierce, strongly influenced by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, saw this as an opportunity not only to acquire land for the railroad, but also to take title to significant other territory from northern Mexico.[3] In the end, territory for the railroad was purchased for $10 million, but Mexico balked at any large scale surrender of territory. In the United States, the debate over the treaty became involved in the sectional dispute over slavery, and no further progress was made before the American Civil War in the planning or construction of a transcontinental railroad.

Contents |

Background

Southern route for the Transcontinental Railroad

Southern commercial conventions

The first concrete plan to construct a transcontinental railroad was presented to Congress in January 1845 by Asa Whitney of New York. While no action was taken, the Memphis commercial convention of 1845 took up the issue. Prominent attendees included John C. Calhoun, Clement C. Clay, Sr., John Bell, William Gwin, and Edmund P. Gaines, but it was James Gadsden of South Carolina who was influential in the convention’s recommendation that a southern route for the proposed railroad, beginning in Texas and ending in San Diego or Mazatlan, be established. It was the hope that such a route would both insure southern prosperity while opening the “West to southern influence and settlement.”[4]

Southern interest in railroads in general, and the Pacific railroad in particular, accelerated after the settlement of the Mexican-American War in 1848. During that War, the topographical officers William H. Emory and James W. Abert had conducted surveys that demonstrated the feasibility of a railroad originating in El Paso or western Arkansas and ending in San Diego. J. D. B. De Bow, the editor of DeBow's Review, and Gadsden both publicized within the South the benefits of building this railroad.[5]

Gadsden had become the president of the South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company in 1839; about a decade later, the company had laid 136 miles of track, spreading west from Charleston, and it was $3 million dollars in debt. Gadsden wanted to connect all Southern railroads into one sectional net.[6] He was concerned about the increasing amount of railroad construction in the North that was resulting in the trade in lumber, farm goods, and manufacturing goods shifting from the traditional north-south route based on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers to an east-west axis that would bypass the South. He also saw Charleston, his home town, losing its prominence as a seaport. In addition, many Southern business interests feared that a northern transcontinental route would cut off the South from trade with the Orient, while other Southerners argued that diversification away from a strictly plantation economy was necessary to keep the South independent from northern bankers.[7]

A Memphis railroad convention was called in October 1849 in response to a separate convention called in St. Louis earlier in the fall. This convention overwhelmingly advocated the construction of a route beginning in Memphis that would connect with an El Paso to San Diego line. Disagreement only arose over the issue of financing. The convention president, Matthew Fontaine Maury of Virginia, preferred strict private financing while John Bell and others thought that Federal land grants to railroad developers would be necessary.[8]

James Gadsden and California

Gadsden had supported nullification in 1831, and he advocated secession by South Carolina in 1850 when California was admitted to the Union as a free state. Gadsden considered slavery “a social blessing” and abolitionists as “the greatest curse of the nation.”[6]

When that secession failed, Gadsden, working with his cousin Isaac Edward Holmes, who had moved to San Francisco in 1851 to practice law, and the California state senator Thomas Jefferson Green, attempted to divide California in two with the southern half allowing slavery. Gadsden planned to establish a slave holding colony based on rice, cotton, and sugar, while building with slave labor, a railroad and highway, originating in either San Antonio or on the Red River, that would transport people to the California gold fields. Towards this end, on December 31, 1851, Gadsden asked Green to secure from the state legislature a large land grant located between the 34th and 36th parallels that would eventually serve as the dividing line for the two California states.[9]

A few months after this Gadsden and 1,200 potential settlers from South Carolina and Florida submitted a petition to the California legislature for permanent citizenship and permission to establish a rural district that would be farmed by "not less than Two Thousand of their African Domestics". The petition stimulated some debate, but it finally died in committee.[10]

Stephen Douglas and land grants

The Compromise of 1850, which created the Utah Territory and the New Mexico Territory, would facilitate a southern route to the West Coast since all territory for the railroad was now organized and would allow for Federal land grants as a financing measure. Competing northern or central routes championed, respectively, by Stephen Douglas of Illinois and Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri would still need to go through unorganized territories.[11] A precedent for using federal land grants had been established when Millard Fillmore signed a bill promoted by Douglas that allowed a Mobile to Chicago railroad to be financed by "federal land grants for the specific purpose of railroad construction."[12] In order to satisfy Southern opposition to the general principle of Federally-supported internal improvements, the land grants would first be transferred to the appropriate state or territorial government which would oversee the final transfer to private developers.[13]

By 1850, however, the majority of the South was not interested in exploiting its advantages in developing a transcontinental railroad or railroads in general. Businessmen like Gadsden, who advocated economic diversification, were in the minority. The Southern economy was based on cotton exports, and then-current transportation networks met the plantation system's needs. There was little home market for an intra-South trade, and in the short term, the best use for capital was to invest it in more slaves and land rather than in taxing it in order to support canals, railroads, roads, or in dredging rivers.[14] Historian Jere W. Roberson wrote:

Southerners might have gained a great deal under the 1850 land grant act had they concentrated their efforts. But continued opposition to Federal aid, filibustering, an unenthusiastic President, the spirit of "Young America", and efforts to build railroads and canals across Central America and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Mexico divided their forces, leaving little time for the Pacific railroad. Moreover, the Compromise of 1850 encouraged Southerners not to antagonize opponents by resurrecting the railroad controversy.[15]

Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo had ended the Mexican-American War, but there were issues affecting both sides that still needed to be resolved: possession of the Mesilla Valley, protection for Mexico from Indian raids, and the right of transit in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

Mesilla Valley

The treaty provided for a joint commission, made up of a surveyor and commissioner from each country, to determine the final boundary between the United States and Mexico. The treaty specified that the Rio Grande Boundary would veer west eight miles north of El Paso. However, there was an 1847 copy of a twenty five year old map attached to the treaty, and actual surveys revealed that El Paso was 36 miles father south and 100 miles further west than the map showed. Mexico favored the map, but the United States put faith in the results of the survey. The disputed territory involved a few thousand square miles and about 3,000 residents, but it also included the Mesilla Valley. This valley bordered the Rio Grande and consisted of flat desert land measuring about 50 miles, north to south, by 200 miles, east to west. This valley was essential for the construction of a transcontinental railroad using a southern route.[16]

John Bartlett of Rhode Island, the United States negotiator, agreed to allow Mexico to retain the Mesillae Valley in exchange for the Santa Rita Mountains, which were believed to have rich copper deposits and some silver and gold that had not yet been mined. This was opposed by southerners in Congress because of the railroad implications, but supported by President Fillmore. Southerners in Congress prevented any action on the approval of this separate border treaty and eliminated any further funding for surveying of the disputed borderland. Bartlett was replaced with Robert Blair Campbell, a pro-railroad politician from Alabama, but Mexico asserted that the commissioners' determinations were valid and prepared to send in troops to enforce the unratified agreement.[17]

Indian raids

Article XI of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo contained a guarantee by the United States to protect Mexicans from cross border raids by native Americans. At the time the treaty was ratified, Secretary of State James Buchanan had believed that the United States had both the commitment and resources to enforce this promise.[18] Historian Richard Kluger, however, described the difficulties of the task:

Commanche, Apache, and other tribal warriors had been punishing Spanish, Mexican, and American intruders into their stark homeland for three centuries and been given no incentive to let up their murderous marauding and pillaging, horse stealing in particular. The U. S. Army had posted nearly 8,000 of its total of 11,000 soldiers along the southwestern boundary, but they could not halt the 75,000 or so native nomads in the region from attacking swiftly and taking refuge among the hills, buttes, and arroyos in a landscape where one’s enemies could be spotted twenty or thirty miles away.[18]

In the five years after approval of the Treaty, the United States had spent $12 million in this area, and General Winfield Scott estimated that costs of five times that amount would be necessary to accomplish the task. Mexican officials, frustrated with the failure of the United States to effectively enforce its guarantee, demanded reparations for the losses inflicted on Mexican citizens by the raids. The United States argued that the Treaty did not require any compensation nor did it require any greater effort to protect Mexicans than was expended in protecting its own citizens. During the Fillmore administration, Mexico claimed damages of $40 million dollars but offered to allow the U. S. to buy out Article XI for $12 million. Fillmore had proposed a settlement that was $10 million less.[18]

Isthmus of Tehuantepec

During negotiations of the treaty, Americans had failed to secure the right of transit across the 125 mile wide Isthmus of Tehuantepec. The idea of building a railroad here had been considered for a long time. In 1842 Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna sold the rights to build a railroad or canal across the isthmus. The deal included land grants 300 miles wide along the right of way for future colonization and development. In 1847 these rights were acquired by a British bank, a development that could lead, Americans feared, to British colonization in violation of the precepts of the Monroe Doctrine. American interest was further piqued with the 1848 discovery of gold in California.[19]

The Memphis commercial convention of 1849 recommended that the United States pursue this trans-isthmus route since it appeared unlikely that a transcontinental railroad would be built anytime soon. Interests in Louisiana were especially adamant about this option, believing that any transcontinental railroad would divert commercial traffic away from the Mississippi and New Orleans. Also showing interest was Peter A. Hargous of New York who ran an import-export business between New York and Vera Cruz. Hargous purchased the rights to the route for $25,000, but realized that the grant had little value unless it was supported by the Mexican and American governments.[20]

In Mexico, topographical officer George W. Hughes reported to Secretary of State John M. Clayton that a railroad across the isthmus was a “feasible and practical” idea. Clayton then instructed Robert P. Letcher, the minister to Mexico, to negotiate a treaty to protect Hargous’ rights. The United States’ proposal gave Mexicans a 20% discount on shipping, guaranteed Mexican rights in the zone, allowed the United States to send in military if necessary, and gave the United States most-favored-nation status for Mexican cargo fees.[21]

The treaty was never finalized. The Clayton-Bulwer Treaty between the United States and Great Britain, which guaranteed the neutrality of any such canal, was finalized in April 1850. The Mexican negotiators, hurt by this agreement which eliminated the ability to play off the U. S. and Britain against each other, accepted the treaty but eliminated the right of the United States to unilaterally intervene militarily. The United States Senate approved the treaty in early 1851, but the Mexican Congress refused to accept the treaty.[22]

In the meantime, however, Hargous proceeded as if the treaty would be approved eventually. Judah P. Benjamin and a committee of New Orleans businessmen joined with Hargous and secured a charter from the Louisiana legislature to create the Tehuantepec Railroad Company. The new company sold stock, and sent survey teams were to Mexico.[23] Hargous started to acquire land even after the Mexican legislature rejected the treaty, a move that led to the Mexicans canceling Hargous’ contract to use the right of way. Hargous put his losses at $5 million and asked the American government to intervene. President Fillmore refused to do so.[22]

Mexico sold the canal franchise, without the land grants, to A. G. Sloo and Associates in New York for $600,000. In March 1853 Sloo contracted with a British company to build a railroad and sought an exclusive contract from the new Pierce Administration to deliver mail from New York to San Francisco. However, Sloo soon defaulted on bank loans and the contract was sold back to Hargous.[24]

Pierce administration

The Pierce administration, which took office in March 1853, had a strong pro-southern, pro-expansion mindset. Louisiana Senator Pierre Soulé was sent to Spain in order to annex Cuba, and expansionists John Y. Mason of Virginia and Solon Borland of Arkansas were appointed as ministers, respectively, to France and Nicaragua.[25] Pierce's Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis, was already on record as favoring a southern route for a transcontinental railroad so southern rail enthusiasts had every reason to be encouraged.[26]

The South as a whole, however, remained divided. In January 1853 Senator Thomas Jefferson Rusk of Texas introduced a bill to create two railroads, one with a northern route and one with a southern route starting below Memphis on the Mississippi River. Under the Rusk legislation, the President would be authorized to select the specific termini and routes as well as the contractors who would build the railroads. Some southerners, however, worried that northern and central interests would leap ahead in the construction, opposed any direct aid to private developers on constitutional grounds. Other southerners preferred the isthmian proposals. An amendment was added to the Rusk bill to prohibit direct aid, but southerners still split their vote in Congress and the proposal failed.[27]

This rejection led to legislative demands, sponsored by William Gwin of California and Salmon P. Chase of Ohio and supported by the railroad interests, for new surveys for possible routes. It was expected by Gwin that a southern route would be approved — both Davis and Robert J. Walker, former secretary of the treasury, supported it, and both were stockholders in a Vicksburg railroad that had plans to build a link to Texas that would join up with the southern route. Davis also argued that the southern route would have an important military application in the likely event of future troubles with Mexico.[28]

Gadsden and Santa Anna

On March 21, 1853, a treaty, initiated in the Fillmore administration, that would provide joint Mexican and American protection for the Sloo grant was signed in Mexico. At the same time that this treaty was received in Washington, Pierce learned that New Mexico Territorial Governor William C. Lane had issued a proclamation claiming the Mesilla Valley as part of New Mexico, leading to protests from Mexico. Pierce was also aware of efforts by France, through its consul in San Francisco, to acquire the Mexican state of Sonora.[29]

Pierce recalled Lane in May and replaced him with David Meriwether of Kentucky. Meriwether was given orders to stay out of the Mesilla Valley until negotiations with Mexico could be completed. With the encouragement of Davis, Pierce also appointed James Gadsden to negotiate with Mexico over the acquisition of additional territory. Secretary of State William L. Marcy gave Gadsden very clear instructions. He was to secure the Mesilla Valley for the purposes of building a railroad through it, convince Mexico that the US had done its best regarding the Indian raids, and elicit Mexican cooperation in the efforts by American citizens to build a canal or railroad across the Tenhuantepec isthmus. Specifically supporting the Sloo interests was not part of the instructions[30]

The Mexican government was going through political and financial turmoil. Looking for a solution, Santa Anna had been returned to power about the same time that Pierce was inaugurated. Santa Anna was willing to deal because of the need for money in order to rebuild his military to defend itself against the United States, but he initially rejected the extension of the border further south to the Sierra Madres. He initially insisted on reparations for the damages caused by the Indian raids but agreed to let an international tribunal resolve this. Gadsden realized that Santa Anna had a need for money and passed this information along to Secretary Marcy.[31]

Marcy and Pierce responded with new instructions. Gadsden was authorized to purchase any of six parcels of land with a price fixed for each. The price would include the settlement of all Indian damages and relieve the United States from any further obligation to protect Mexicans. $50 million would have bought Baja and a large portion of its northwestern Mexican states while $15 million bought the 38,000 square miles of desert necessary for the railroad plans.[31]

Santa Anna was put off by "Gadsden’s antagonistic manner." Gadsden had advised Santa Anna that "the spirit of the age" would soon lead the northern states to secede so he might as well sell them now. The Mexican President was further upset by William Walker's attempt to capture the Baja with 50 other troops and annex Sonora.[32] Gadsden disavowed any government backing of Walker, who was expelled by the US and placed on trial as a criminal, but Santa Anna was still not convinced that the United States did not have further aggressions aimed at Mexican territory.[33] For Santa Anna, the best he could hope for was to get as much money for as little territory as possible.[2] When Great Britain rejected Mexican requests to assist in the negotiations, Santa Anna opted for the $15 million package.[33]

Ratification

Pierce and his cabinet began debating the treaty among themselves in January 1854. They were disappointed in the amount of territory secured and some of the terms, but after considering the matter for close to a month they submitted it to the Senate on February 10.[34]

The treaty reached the Senate as it was focused on the debate over the Kansas-Nebraska Act. On April 17, after much debate, the Senate voted 27 to 18 in favor of the treaty, falling three votes short of the necessary two-thirds required for treaty approval. After this defeat, Secretary Davis and southern senators pressured Pierce to add protection for the Sloo grant to the treaty and add language requiring Mexico “to protect with its whole power the prosecution, preservation, and security of the work [the canal]” while allowing the United States to act unilaterally “when it may feel sanctioned and warranted by the public or international law.” The territory to be acquired was reduced by 9,000 square miles and the price changed $15 million to $10 million. This version of the treaty was successfully passed by a vote of 33 to 12. The reduction in territory had been intended to accommodate northern senators who opposed the acquisition of additional slave territory, but the final vote still showed northerners split 12 to 12. Gadsden took the revised treaty back to Santa Anna, who accepted the changes.[35]

While the land was now available for the southern railroad, the issue had now become too strongly associated with the sectional debate over slavery. Roberson wrote:

The unfortunate debates in 1854 left an indelible mark on the course of national politics and the Pacific railroad for the remainder of the antebellum period. It was becoming increasingly difficult, if not outright impossible, to consider any proposal that could not somehow be construed as relating to slavery and, therefore, sectional issues. Although few people fully realized it at the close of 1854, sectionalism had taken such a firm, unrelenting hold on the nation that completion of an antebellum Pacific railroad was prohibited. Money, interest, and enthusiasm were devoted to emotion-filled topics, not the Pacific railroad.[36]

The effect was such that railroad development, which accelerated in the North, stagnated in the South.[37]

Post-ratification controversy

As originally envisioned, the purchase would have encompassed a much larger region, extending far enough south to include most of the current Mexican states of Coahuila, Chihuahua, Sonora, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas as well as all of the Baja California peninsula. These original boundaries were opposed not only by the Mexican people but also by anti-slavery U.S. Senators who saw the purchase as tantamount to the acquisition of more slave territory. Even the small strip of land that was ultimately acquired was enough to anger the Mexican people, who saw Santa Anna's actions as yet another betrayal of their country and watched in dismay as he squandered the funds generated by the Purchase. Even today, Mexican historians view the deal negatively and believe that it continues to define the United States-Mexico relationship.[2]

The purchased lands were initially appended to the existing New Mexico Territory. To help control the new land, the United States Army established Fort Buchanan on Sonoita Creek in present-day southern Arizona on November 17, 1856. The difficulty of governing the new areas from the territorial capital at Santa Fe led to efforts as early as 1856 to organize a new territory out of the southern portion of the New Mexico Territory. Many of the early settlers in the region were, however, pro-slavery and sympathetic to the South, resulting in an impasse in Congress as to how best to reorganize the territory.

The shifting of the Rio Grande would cause a later dispute over the boundary between Purchase lands and those of the state of Texas, known as the Country Club Dispute.

U.S. statehood

In 1861, during the American Civil War, the Confederacy formed the Confederate Territory of Arizona, including in the new territory mainly areas acquired by the Gadsden Purchase. In 1863, using a north-to-south dividing line, the Union created its own Arizona Territory out of the western half of the New Mexico Territory. The new U.S. Arizona Territory also included most of the lands acquired in the Gadsden Purchase. This territory would be admitted into the Union as the State of Arizona on February 14, 1912, the last area in the lower 48 to receive statehood.

Eventual railroad development

The Southern Pacific Railroad from Los Angeles reached Yuma, Arizona in 1877, Tucson in March 1880, El Paso in May 1881, and completed the second transcontinental railroad in December 1881. Ironically, most of the route was north of the Gadsden Purchase.

The remainder of the Gila Valley pre-Purchase border area was traversed by the Arizona Eastern Railway by 1899 and the Copper Basin Railway by 1904, except for a 20-mile section in the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation, from today's San Carlos Lake to Winkelman at the mouth of the San Pedro River, including the Needle's Eye Wilderness.

The section of US 60 about 20 miles to the northwest, between Superior and Miami via Top-of-the-World, takes an alternate route (17.4 road miles) between the Magma Arizona Railroad and Arizona Eastern Railway railheads on each side of this gap and is well north of the Gadsden Purchase.[38][39]

Population

The El Paso suburb of Sunland Park (pop. 13,309 in 2000) in Doña Ana County is the largest New Mexico community in the Purchase; the Hidalgo County seat of Lordsburg and Luna County seat of Deming are both north of the pre-Purchase US-Mexico border.

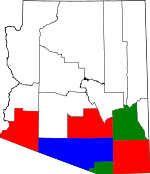

Arizona county boundaries do not follow the Purchase boundary, but six counties have most of their population in the Purchase area. Four of them contain areas outside the Purchase, but those areas have low population, with the exception of northeast Pinal County including Apache Junction and Florence. Maricopa County also extends south into the Purchase, but this area is also low in population.

| County | Seat | Pop. | Area (mi²) |  |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cochise | Bisbee | 117755 | 6,219 | ||

| Graham | Safford | 33489 | 4,641 | ||

| Pima | Tucson | 843746 | 9,189 | ||

| Pinal | Florence | 179727 | 5,374 | ||

| Santa Cruz | Nogales | 38381 | 1,238 | ||

| Yuma | Yuma | 160026 | 5,519 | ||

| Total | 1373124 |

Notes

- ↑ William L. Marcy. "The Avalon Project: Gadsden Purchase Treaty: December 30, 1853". Yale University. Retrieved on 2008-10-10. The Purchase treaty defines the new border as "up the middle of that river (the Rio Grande) to the point where the parallel of 31° 47' north latitude crosses the same ; thence due west one hundred miles; thence south to the parallel of 31° 20' north latitude; thence along the said parallel of 31° 20' to the 111th meridian of longitude west of Greenwich ; thence in a straight line to a point on the Colorado River twenty English miles below the junction of the Gila and Colorado rivers; thence up the middle of the said river Colorado until it intersects the present line between the United States and Mexico." The new border included a few miles of the Colorado River at the western end; the remaining land portion consisted of line segments between points, including at the Colorado River, west of Nogales at , near AZ-NM-Mexico tripoint at , the eastern corners of NM southern bootheel (Hidalgo County) at , and the west bank of Rio Grande at

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Ibarra, Ignacio (2004-02-12). "Land sale still thorn to Mexico: Historians say U.S. imperialism behind treaty", Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved on 2007-10-04.

- ↑ Nevins p. 84

- ↑ Roberson p. 163-164

- ↑ Roberson p. 165

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Richards p. 125

- ↑ Kluger p. 485

- ↑ Roberson p. 166

- ↑ Richards p. 126

- ↑ Richards p. 127

- ↑ Kluger p. 487. Roberson p. 169

- ↑ Roberson p. 168

- ↑ Kluger p. 487

- ↑ Kluger p. 488

- ↑ Roberson p. 169

- ↑ Kluger p. 491

- ↑ Kluger pp. 491-492. Roberson p. 171

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Kluger p. 492

- ↑ Roberson p. 182. Kluger p. 493

- ↑ Roberson p. 182. Kluger p. 493

- ↑ Kluger p. 493-494. Roberson p. 182

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Kluger p. 494

- ↑ Roberson p. 182

- ↑ Kluger p. 494-495

- ↑ Nevins p. 48

- ↑ Roberson p. 170

- ↑ Roberson pp. 170- 171

- ↑ Roberson p. 172. Kluger p. 490

- ↑ Nichols p. 265

- ↑ Nichols p. 266. Kluger p. 496. Roberson p. 183

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Kluger pp. 497-498

- ↑ Isenberg, David (2008-09-28). "Dogs of War: Mercenary hero William Walker", Middle East Times. Retrieved on 2008-10-08.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Kluger p. 498-499

- ↑ Nichols p. 325

- ↑ Kluger p. 502-503. Potter p. 183

- ↑ Roberson p. 180

- ↑ Kluger p. 504

- ↑ Arizona Railroad Map. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- ↑ Arizona Eastern Railway Map. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

Bibliography

- Kluger, Richard. Seizing Destiny: How America Grew From Sea to Shining Sea. (2007) ISBN 978-0-375-41341-4

- Nevins, Allan. Ordeal of the Union: A House Dividing 1852-1857. (1947) SBN 684-10424-5.

- Nichols, Roy Franklin. Franklin Pierce: Young Hickory of the Granite Hills. (1969 2nd. Edition) 8122-7044-4

- Potter, David N. The Impending Crisis 1848-1861. (1976) ISBN 0-06-131929-5

- Richards, The California Gold Rush and the Coming of the Civil War. (2007) ISBN 0-307-26520-X

- Roberson, Jere W. "The South and the Pacific Railroad, 1845-1855." The Western Historical Quarterly, Vol. 5, No. 2, (Apr., 1974), pp. 163-186. JSTOR

See also

- U.S.-Mexico border

- Historic regions of the United States

External links

- US Geological Survey USGS Public Lands Survey Map including survey township (6 mile) lines

- 1855 map with some proposed railroad routes

- National Park Service Map including route of the Southern Pacific railroad finally built in the 1880s

- US Department of State - Gadsden Purchase, 1853-1854, Office of the Historian

|

||||||||