Megabat

| Megabat Fossil range: Mid Oligocene to Recent |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

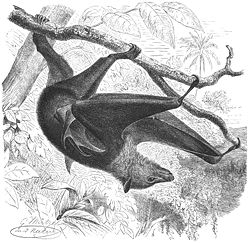

Large flying fox, Pteropus vampyrus

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Subfamilies | ||||||||||||

|

Macroglossinae |

Megabats is the term used informally to refer to bats of the family Pteropodidae. They are also referred to as fruit bats, old world fruit bats, or flying foxes. According to the most commonly used classification, they constitute a single suborder Megachiroptera, within the order Chiroptera (bats).

Contents |

Description

The megabat, contrary to its name, is not always large: the smallest species is 6 centimeters (2.4 inches) long and thus smaller than some microbats. The largest reach 40 cm (16 inches) in length and attain a wingspan of 150 cm (5 feet), weighing in at nearly 1 kg (more than 2 pounds). Most fruit bats have large eyes, allowing them to orient visually in the twilight of dusk and inside caves and forests.

The sense of smell is excellent in these creatures. In contrast to the microbats, the fruit bats do not, as a rule, use echolocation (with one exception, the Egyptian fruit bat Rousettus egyptiacus, which uses high-pitched clicks to navigate in caves).

In specimens of the Egyptian fruit bat the epidemical Marburg virus was found in 2007, confirming the suspicion that this species may be a reservoir for this dangerous virus.[1]

Diet

Fruit bats are frugivorous or nectarivorous, i.e., they eat fruits or lick nectar from flowers. Often the fruits are crushed and only the juices consumed. The teeth are adapted to bite through hard fruit skins. Large fruit bats must land in order to eat fruit, while the smaller species are able to hover with flapping wings in front of a flower or fruit.

Importance

Frugivorous bats aid the distribution of plants (and therefore, forests) by carrying the fruits with them and spitting the seeds or eliminating them elsewhere. Nectarivores actually pollinate visited plants. They bear long tongues that are inserted deep into the flower; pollen thereby passed to the bat is then transported to the next blossom visited, pollinating it. This relationship between plants and bats is a form of mutualism known as chiropterophily. Examples of plants that benefit from this arrangement include the baobabs of the genus Adansonia and the sausage tree (Kigelia).

Fruit Bats as Reservoirs of Ebola Virus

Researchers tested for presence of the Ebola virus in fruit bats between 2001 and 2003. Three species of bats tested positive for Ebola, but had no symptoms of the virus. This indicates that the bats may be acting as a reservoir for the virus. Of the infected animals identified during these field collections, immunoglobulin G (IgG) specific for Ebola virus was detected in Hypsignathus monstrosus, Epomops franqueti, and Myonycteris torquata.

Classification

Bats are usually thought to belong to one of two monophyletic groups, a view that is reflected in their classification into two suborders (Megachiroptera and Microchiroptera). According to this hypothesis, all living megabats and microbats are descendants of a common ancestor species that was already capable of flight. However, there have been other views, and a vigorous debate persists to this date. For example, in the 1980s and 1990s, some researchers proposed (based primarily on the similarity of the visual pathways) that the Megachiroptera were in fact more closely affiliated with the primates than the Microchiroptera, with the two groups of bats having therefore evolved flight via convergence (see Flying primates theory).[2] However, a recent flurry of genetic studies confirms the more longstanding notion that all bats are indeed members of the same clade, the Chiroptera.[3][4] Other studies have recently suggested that certain families of microbats (possibly the horseshoe bats, mouse-tailed bats and the false vampires) are evolutionarily closer to the fruit bats than to other microbats.[3][5]

Mindoro Stripe-Faced Fruitbat

On September 17, 2007, a new species of flying fox, or fruit bat — orange-coloured with a distinctive, white-striped face — was discovered in a protected wildlife area in the Sablayan region, Mindoro, Philippines. The Mindoro Stripe-Faced Fruitbat was discovered through a joint research effort by the University of Kansas's Biodiversity Research Center and the Comparative Biogeography and Conservation of Philippine Vertebrates (CBCPV). The Journal of Mammalogy published its details. The total number of bat species in the Philippines is 74, with 26 unique to the Philippines.[6]

List of genera

The family Pteropodidae is divided into two subfamilies with 173 total species, represented by 42 genera:

Subfamily Macroglossinae

- Macroglossus (long-tongued fruit bats)

- Megaloglossus (Woermann's Bat)

- Eonycteris (dawn fruit bats)

- Syconycteris (blossom bats)

- Melonycteris

- Notopteris (long-tailed fruit bat)

Subfamily Pteropodinae

- Eidolon (straw-coloured fruit bats)

- Rousettus (rousette fruit bats)

- Boneia (considered subgenus of Rousettus by most authors[7]

- Myonycteris (little collared fruit bats)

- Pteropus (flying foxes)

- Acerodon (including Giant golden-crowned flying fox)

- Neopteryx

- Pteralopex

- Styloctenium

- Dobsonia (bare-backed fruit bats)

- Aproteles (Bulmer's fruit bat)

- Harpyionycteris (Harpy Fruit Bat)

- Plerotes (D'Anchieta's Fruit Bat)

- Hypsignathus (Hammer-headed bat)

- Epomops (epauleted bats)

- Epomophorus (epauleted fruit bats)

- Micropteropus (dwarf epauleted bats)

- Nanonycteris (Veldkamp's Bat)

- Scotonycteris

- Casinycteris (Short-palated Fruit Bat)

- Cynopterus (dog-faced fruit bats or short-nosed fruit bats)

- Megaerops

- Ptenochirus (musky fruit bats)

- Dyacopterus (Dayak fruit bats)

- Chironax (black-capped fruit bat)

- Thoopterus (Swift Fruit Bat)

- Sphaerias (Blanford's Fruit Bat)

- Balionycteris (spotted-winged fruit bat)

- Aethalops (pygmy fruit bat)

- Penthetor (dusky fruit bats)

- Haplonycteris (Fischer's pygmy fruit bat or Philippine dwarf fruit bat)

- Otopteropus (Luzon dwarf fruit bat)

- Alionycteris (Mindanao dwarf fruit bat)

- Latidens (Salim Ali's fruit bat)

- Nyctimene (tube-nosed fruit bat)

- Paranyctimene (lesser tube-nosed fruit bats)

- Mirimiri (Fijian Monkey-faced Bat)

Fruit bats in popular culture

Because of their large size and somewhat "spectral" appearance, fruit bats are sometimes used in horror movies to represent vampires or to otherwise lend an aura of spookiness. In reality, as noted above, the bats of this group are purely herbivorous creatures and pose no direct threat to human beings, baby cows, or ill children. Some works of fiction are more in line with this fact, portraying fruit bats as sympathetic or even featuring them as characters. For example, in the book series Silverwing by Kenneth Oppel, a fruit bat named Java is one of the main characters in the final book of the series. In Stellaluna, a popular children's book by Janell Cannon, the story revolves around the plight of a young fruit bat who is separated from her mother.

See also

- Mammals of Borneo

- Cynopterus

- Penthetor

Footnotes

- ↑ "Deadly Marburg virus discovered in fruit bats". msnbc (August 21, 2007). Retrieved on 2008-03-11.

- ↑ Pettigrew JD, Jamieson BG, Robson SK, Hall LS, McAnally KI, Cooper HM, 1989, Phylogenetic relations between microbats, megabats and primates (Mammalia: Chiroptera and Primates). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B, Biological Sciences 325(1229):489-559

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Eick, GN; Jacobs, DS; Matthee, CA (September 2005). "A nuclear DNA phylogenetic perspective on the evolution of echolocation and historical biogeography of extant bats (chiroptera)" (Free full text). Molecular biology and evolution 22 (9): 1869–86. doi:. PMID 15930153. http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long.

- ↑ "Primitive Early Eocene bat from Wyoming and the evolution of flight and echolocation". Nature (2008-02-14). doi:10.1038/nature06549. Retrieved on 2008-07-03. "recent studies unambiguously support bat monophyly"

- ↑ Adkins RM, Honeycutt RL (1991). "Molecular phylogeny of the superorder Archonta" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.S.A. 88 (22): 10317–10321. PMID 1658802. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/reprint/88/22/10317.pdf.

- ↑ New bat species discovered in Philippines Yahoo.com.

- ↑ Mammal Species of the World - Browse: bidens

References

- Myers, P. 2001. "Pteropodidae" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed December 26, 2006 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Pteropodidae.html.

- Springer, M. S.; et al (28 January 2005). "A Molecular Phylogeny for Bats Illuminates Biogeography and the Fossil Record". Science 307: 580. doi:. PMID 15681385.

- Nature, Vol 438, 1 December 2005 at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16319873

- Bat World Sanctuary

- Rodrigues Fruit Bats

- Bat Conservation International

- Criticism of the molecular evidence for bat monophyly

- Brief history of Megachiroptera / Megabats