Fruit

The term fruit has different meanings dependent on context, and the term is not synonymous in food preparation and biology. In botany, which is the scientific study of plants, fruits are the ripened ovaries of flowering plants. In many plant species, the fruit includes the ripened ovary and surrounding tissues. Fruits are the means by which flowering plants disseminate seeds, and the presence of seeds indicates that a structure is most likely a fruit, though not all seeds come from fruits.[1] No single terminology really fits the enormous variety that is found among plant fruits.[2] The term 'false fruit' (pseudocarp, accessory fruit) is sometimes applied to a fruit like the fig (a multiple-accessory fruit; see below) or to a plant structure that resembles a fruit but is not derived from a flower or flowers. Some gymnosperms, such as yew, have fleshy arils that resemble fruits and some junipers have berry-like, fleshy cones. The term "fruit" has also been inaccurately applied to the seed-containing female cones of many conifers.[3]

Contents |

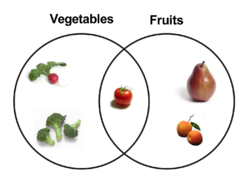

Botanic fruit and culinary fruit

Many true fruits, in a botanical sense, are treated as vegetables in cooking and food preparation because they are not sweet. These botanical fruits include cucurbits (e.g., squash, pumpkin, and cucumber), tomato, peas, beans, corn, eggplant, and sweet pepper, spices, such as allspice and chillies.[4] Occasionally, though rarely, a culinary "fruit" is branded as a true fruit in the botanical sense. For example, rhubarb is often referred to as a fruit, because it is used to make sweet desserts such as pies, though only the petiole of the rhubarb plant is edible.[5] In the culinary sense, a fruit is usually any sweet tasting plant product associated with seed(s), a vegetable is any savoury or less sweet plant product, and a nut any hard, oily, and shelled plant product.[6]

Although a nut is a type of fruit, it is also a popular term for edible seeds, such as peanuts (which are actually a legume) and pistachios.[7] Technically, a cereal grain is a fruit termed a caryopsis. However, the fruit wall is very thin and fused to the seed coat so almost all of the edible grain is actually a seed. Therefore, cereal grains, such as corn, wheat and rice are better considered edible seeds, although some references list them as fruits.[8] Edible gymnosperm seeds are often misleadingly given fruit names, e.g. pine nuts, ginkgo nuts, and juniper berries. A Folk taxonomy is a vernacular naming system which describes how non-scientists categorize items.

Fruit development

A fruit is a ripened ovary. Inside the ovary is one or more ovules where the megagametophyte contains the megagamete or egg cell.[9] The ovules are fertilized in a process that starts with pollination, which involves the movement of pollen from the stamens to the stigma of flowers. After pollination, a tube grows from the pollen through the stigma into the ovary to the ovule and sperm are transferred from the pollen to the ovule, within the ovule the sperm unites with the egg, forming a diploid zygote. Fertilization in flowering plants involving both plasmogamy, the fusing of the sperm and egg protoplasm and karyogamy, the union of the sperm and egg nucleus.[10] When the sperm enters the nucleus of the ovule and joins with the megagamete and the endosperm mother cell, the fertilization process is completed.[11] As the developing seeds mature, the ovary begins to ripen. The ovules develop into seeds and the ovary wall, the pericarp, may become fleshy (as in berries or drupes), or form a hard outer covering (as in nuts). In some cases, the sepals, petals and/or stamens and style of the flower fall off. Fruit development continues until the seeds have matured. In some multiseeded fruits, the extent to which the flesh develops is proportional to the number of fertilized ovules.[12]

The wall of the fruit, developed from the ovary wall of the flower, is called the pericarp. The pericarp is often differentiated into two or three distinct layers called the exocarp (outer layer - also called epicarp), mesocarp (middle layer), and endocarp (inner layer). In some fruits, especially simple fruits derived from an inferior ovary, other parts of the flower (such as the floral tube, including the petals, sepals, and stamens), fuse with the ovary and ripen with it. The plant hormone ethylene causes ripening. When such other floral parts are a significant part of the fruit, it is called an accessory fruit. Since other parts of the flower may contribute to the structure of the fruit, it is important to study flower structure to understand how a particular fruit forms.[3]

Fruits are so diverse that it is difficult to devise a classification scheme that includes all known fruits. Many common terms for seeds and fruit are incorrectly applied, a fact that complicates understanding of the terminology. Seeds are ripened ovules; fruits are the ripened ovaries or carpels that contain the seeds. To these two basic definitions can be added the clarification that in botanical terminology, a nut is not a type of fruit and not another term for seed, on the contrary to common terminology.[4]

There are three basic types of fruits:

Simple fruit

Simple fruits can be either dry or fleshy, and result from the ripening of a simple or compound ovary with only one pistil. Dry fruits may be either dehiscent (opening to discharge seeds), or indehiscent (not opening to discharge seeds).[13] Types of dry, simple fruits, with examples of each, are:

- achene - (buttercup, strawberry seeds)

- capsule - (Brazil nut)

- caryopsis - (wheat)

- fibrous drupe - (coconut, walnut)

- follicle - (milkweed)

- legume - (pea, bean, peanut)

- loment

- nut - (hazelnut, beech, oak acorn)

- samara - (elm, ash, maple key)

- schizocarp - (carrot)

- silique - (radish)

- silicle - (shepherd's purse)

- utricle - (beet)

Fruits in which part or all of the pericarp (fruit wall) is fleshy at maturity are simple fleshy fruits. Types of fleshy, simple fruits (with examples) are:

- berry - (redcurrant, gooseberry, tomato, avocado)

- stone fruit or drupe (plum, cherry, peach, apricot, olive)

- false berry - Epigynous accessory fruits (banana, cranberry, strawberry (edible part).)

- pome - accessory fruits (apple, pear, rosehip)

Aggregate fruit

An aggregate fruit, or etaerio, develops from a flower with numerous simple pistils.[14] An example is the raspberry, whose simple fruits are termed drupelets because each is like a small drupe attached to the receptacle. In some bramble fruits (such as blackberry) the receptacle is elongated and part of the ripe fruit, making the blackberry an aggregate-accessory fruit.[15] The strawberry is also an aggregate-accessory fruit, only one in which the seeds are contained in achenes.[16] In all these examples, the fruit develops from a single flower with numerous pistils.

Some kinds of aggregate fruits are called berries, yet in the botanical sense they are not.

Multiple fruit

A multiple fruit is one formed from a cluster of flowers (called an inflorescence). Each flower produces a fruit, but these mature into a single mass.[17] Examples are the pineapple, edible fig, mulberry, osage-orange, and breadfruit.

In the photograph on the right, stages of flowering and fruit development in the noni or Indian mulberry (Morinda citrifolia) can be observed on a single branch. First an inflorescence of white flowers called a head is produced. After fertilization, each flower develops into a drupe, and as the drupes expand, they become connate (merge) into a multiple fleshy fruit called a syncarpet.[18]

There are also many dry multiple fruits, e.g.

- Tuliptree, multiple of samaras.

- Sweet gum, multiple of capsules.

- Sycamore and teasel, multiple of achenes.

- Magnolia, multiple of follicles.

Fruit chart

To summarize common types of fruit (examples follow in the table below):

- Berry -- simple fruit and seeds created from a single ovary

- Pepo -- Berries where the skin is hardened, like cucurbits

- Hesperidium -- Berries with a rind, like most citrus fruit

- Epigynous berries(false berries) -- Epigynous fruit made from a part of the plant other than a single ovary

- Compound fruit, which includes:

- Aggregate fruit -- multiple fruits with seeds from different ovaries of a single flower

- Multiple fruit -- fruits of separate flowers, packed closely together

- Other accessory fruit -- where the edible part is not generated by the ovary

| True berry | Pepo | Hesperidium | False berry (Epigynous) | Aggregate fruit | Multiple fruit | Other accessory fruit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blackcurrant, Redcurrant, Gooseberry, Tomato, Eggplant, Guava, Lucuma, Chili pepper, Pomegranate, Avocado, Kiwifruit, Grape, | Pumpkin, Gourd, Cucumber, Melon | Orange, Lemon, Lime, Grapefruit | Banana, Cranberry, Blueberry | Blackberry, Raspberry, Boysenberry, Hedge apple | Pineapple, Fig, Mulberry | Apple, Apricot, Peach, Cherry, Green bean, Sunflower seed, Strawberry, plum, |

Seedless fruits

Seedlessness is an important feature of some fruits of commerce. Commercial cultivars of bananas and pineapples are examples of seedless fruits. Some cultivars of citrus fruits (especially navel oranges and mandarin oranges), table grapes, grapefruit, and watermelons are valued for their seedlessness. In some species, seedlessness is the result of parthenocarpy, where fruits set without fertilization. Parthenocarpic fruit set may or may not require pollination. Most seedless citrus fruits require a pollination stimulus; bananas and pineapples do not. Seedlessness in table grapes results from the abortion of the embryonic plant that is produced by fertilization, a phenomenon known as stenospermocarpy which requires normal pollination and fertilization.[19]

Seed dissemination

Variations in fruit structures largely depend on the mode of dispersal of the seeds they contain. This dispersal can be achieved by animals, wind, water, or explosive dehiscence.[20]

Some fruits have coats covered with spikes or hooked burrs, either to prevent themselves from being eaten by animals or to stick to the hairs, feathers or legs of animals, using them as dispersal agents. Examples include cocklebur and unicorn plant.[21][22]

The sweet flesh of many fruits is "deliberately" appealing to animals, so that the seeds held within are eaten and "unwittingly" carried away and deposited at a distance from the parent. Likewise, the nutritious, oily kernels of nuts are appealing to rodents (such as squirrels) who hoard them in the soil in order to avoid starving during the winter, thus giving those seeds that remain uneaten the chance to germinate and grow into a new plant away from their parent.[4]

Other fruits are elongated and flattened out naturally and so become thin, like wings or helicopter blades, e.g. maple, tuliptree and elm. This is an evolutionary mechanism to increase dispersal distance away from the parent via wind. Other wind-dispersed fruit have tiny parachutes, e.g. dandelion and salsify.[20]

Coconut fruits can float thousands of miles in the ocean to spread seeds. Some other fruits that can disperse via water are nipa palm and screw pine.[20]

Some fruits fling seeds substantial distances (up to 100 m in sandbox tree) via explosive dehiscence or other mechanisms, e.g. impatiens and squirting cucumber.[23]

Uses

Many hundreds of fruits, including fleshy fruits like apple, peach, pear, kiwifruit, watermelon and mango are commercially valuable as human food, eaten both fresh and as jams, marmalade and other preserves. Fruits are also in manufactured foods like cookies, muffins, yoghurt, ice cream, cakes, and many more. Many fruits are used to make beverages, such as fruit juices (orange juice, apple juice, grape juice, etc) or alcoholic beverages, such as wine or brandy.[24] Apples are often used to make vinegar.Fruits are also used for gift giving, Fruit Basket and Fruit Bouquet are some common forms of fruit gifts.

Many vegetables are botanical fruits, including tomato, bell pepper, eggplant, okra, squash, pumpkin, green bean, cucumber and zucchini.[25] Olive fruit is pressed for olive oil. Spices like vanilla, paprika, allspice and black pepper are derived from berries.[26]

Nutritional value

Fruits are generally high in fiber, water and vitamin C. Fruits also contain various phytochemicals that do not yet have an RDA/RDI listing under most nutritional factsheets, and which research indicates are required for proper long-term cellular health and disease prevention. Regular consumption of fruit is associated with reduced risks of cancer, cardiovascular disease, stroke, Alzheimer disease, cataracts, and some of the functional declines associated with aging.[27]

Nonfood uses

Because fruits have been such a major part of the human diet, different cultures have developed many different uses for various fruits that they do not depend on as being edible. Many dry fruits are used as decorations or in dried flower arrangements, such as unicorn plant, lotus, wheat, annual honesty and milkweed. Ornamental trees and shrubs are often cultivated for their colorful fruits, including holly, pyracantha, viburnum, skimmia, beautyberry and cotoneaster.[28]

Fruits of opium poppy are the source of opium which contains the drugs morphine and codeine, as well as the biologically inactive chemical theabaine from which the drug oxycodone is synthysized.[29] Osage orange fruits are used to repel cockroaches.[30] Bayberry fruits provide a wax often used to make candles.[31] Many fruits provide natural dyes, e.g. walnut, sumac, cherry and mulberry.[32] Dried gourds are used as decorations, water jugs, bird houses, musical instruments, cups and dishes. Pumpkins are carved into Jack-o'-lanterns for Halloween. The spiny fruit of burdock or cocklebur were the inspiration for the invention of Velcro.[33]

Coir is a fibre from the fruit of coconut that is used for doormats, brushes, mattresses, floortiles, sacking, insulation and as a growing medium for container plants. The shell of the coconut fruit is used to make souvenir heads, cups, bowls, musical instruments and bird houses.[34]

Production

India is world leader in fresh fruit production followed by Vietnam and then China.

| Top Ten fresh fruit Producers — 2005 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Production (Int $1000) | Footnote | Production (MT) | Footnote |

| 1,052,766 | C | 6,600,000 | F | |

| 438,652 | C | 2,750,000 | F | |

| 271,167 | C | 1,790,000 | F | |

| 255,216 | C | 1,600,000 | F | |

| 223,314 | C | 1,400,000 | F | |

| 223,314 | C | 1,400,000 | F | |

| 183,436 | C | 1,150,000 | F | |

| 129,203 | C | 810,000 | F | |

| 82,945 | C | 520,000 | F | |

| 78,160 | C | 490,000 | F | |

| No symbol = official figure,F = FAO estimate, * = Unofficial figure, C = Calculated figure; Production in Int $1000 have been calculated based on 1999-2001 international prices |

||||

Philippines is world leader in tropical fresh fruit production followed by Indonesia and then India.

| Top Ten tropical fresh fruit Producers — 2005 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Production (Int $1000) | Footnote | Production (MT) | Footnote |

| 389,164 | C | 3,400,000 | F | |

| 377,718 | C | 3,300,000 | F | |

| 335,368 | C | 2,930,000 | F | |

| 177,413 | C | 2,164,000 | F | |

| 131,629 | C | 1,150,000 | F | |

| 83,556 | C | 730,000 | F | |

| 60,893 | C | 532,000 | F | |

| 55,513 | C | 485,000 | F | |

| 31,934 | C | 279,000 | F | |

| 28,615 | C | 250,000 | F | |

| No symbol = official figure, F = FAO estimate, * = Unofficial figure, C = Calculated figure; Production in Int $1000 have been calculated based on 1999-2001 international prices |

||||

See also

- List of culinary fruits

- Fruit trees

- Tutti frutti

- Fruitarianism

References

- ↑ Lewis, Robert A. (January 1 2002). CRC Dictionary of Agricultural Sciences. CRC Press. pp. 375–376. ISBN 0-8493-2327-4. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0849323274&id=TwRUZK0WTWAC&pg=PA375&lpg=PA375&dq=fruit&sig=qv05UIJxg5T_NmacdW8YixDnDAo.

- ↑ Schlegel, Rolf H J (January 1 2003). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Plant Breeding and Related Subjects. Haworth Press. pp. 177. ISBN 1-56022-950-0. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=1560229500&id=7J-3fD67RqwC&pg=PA177&lpg=PA177&vq=fruit&dq=acarpous&sig=LUVMFeCyejNiIUKgcwnMLl32wGs.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Mauseth, James D. (April 1 2003). Botany: An Introduction to Plant Biology. Jones and Bartlett. pp. 271–272. ISBN 0-7637-2134-4. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0763721344&id=0DfYJsVRmUcC&pg=PA271&lpg=PA271&sig=s2WaDwTzo0sofme_Hj5DamgRFQA.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 McGee, Harold (November 16 2004). On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. Simon and Schuster. pp. 247–248. ISBN 0-684-80001-2. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0684800012&id=iX05JaZXRz0C&pg=PA247&lpg=PA247&vq=Fruit&dq=On+Food+And+Cooking&sig=sxt0wE3J41Afme7D6IbeEeAE920.

- ↑ McGee. On Food and Cooking. pp. 367. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0684800012&id=iX05JaZXRz0C&pg=PA367&lpg=PA367&vq=rhubarb&dq=On+Food+And+Cooking&sig=7TorpakpzTCQfrRZayxOmPyZ_1s.

- ↑ For a Supreme Court of the United States ruling on the matter, see Nix v. Hedden.

- ↑ McGee. On Food and Cooking. pp. 501. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0684800012&id=iX05JaZXRz0C&pg=PA501&lpg=PA501&vq=nut&dq=On+Food+And+Cooking&sig=o2G0ZjyWTWnMsNerGjkZQ2hk_w8.

- ↑ Lewis. CRC Dictionary of Agricultural Sciences. pp. 238. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0849323274&id=TwRUZK0WTWAC&pg=PA238&lpg=PA238&vq=cereal&dq=fruit&sig=5e5ElNUQ8LAQf1_mKsOF-HLSrFc.

- ↑ http://www.palaeos.com/Plants/Lists/Glossary/GlossaryL.html#M

- ↑ Mauseth, James D. (2003). Botany: an introduction to plant biology. Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. pp. 258. ISBN 978-0-7637-2134-3.

- ↑ Rost, Thomas L.; Weier, T. Elliot; Weier, Thomas Elliot (1979). Botany: a brief introduction to plant biology. New York: Wiley. pp. 135–37. ISBN 0-471-02114-8.

- ↑ Mauseth. Botany. Chapter 9: Flowers and Reproduction. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0763721344&id=0DfYJsVRmUcC&pg=PP14&lpg=PP11&sig=fxnTedUCSETHvzOygbqEbQuwk-g.

- ↑ Schlegel. Encyclopedic Dictionary. pp. 123. http://books.google.com/books?id=7J-3fD67RqwC&visbn=1560229500&dq=acarpous&pg=PA123&lpg=PA123&sig=mFka90ytIY0ymsbOk40-U--1h28.

- ↑ Schlegel. Encyclopedic Dictionary. pp. 16. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=1560229500&id=7J-3fD67RqwC&pg=PA16&lpg=PA16&vq=Aggregate+fruit&dq=acarpous&sig=Muxd7lDu6N4K7272-3Eh9VUZwQU.

- ↑ McGee. On Food and Cooking. pp. 361–362. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0684800012&id=iX05JaZXRz0C&pg=PA361&lpg=PA361&vq=raspberry&dq=On+Food+And+Cooking&sig=0wKBQUHIAP1jhRusTCw64TGfYoQ.

- ↑ McGee. On Food and Cooking. pp. 364–365. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0684800012&id=iX05JaZXRz0C&pg=PA364&lpg=PA364&vq=strawberry&dq=On+Food+And+Cooking&sig=bKEBM5unYQam-pn6AYQSyKhWe_o.

- ↑ Schlegel. Encyclopedic Dictionary. pp. 282. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=1560229500&id=7J-3fD67RqwC&pg=PA282&lpg=PA282&vq=Multiple+fruit&dq=acarpous&sig=mnPOH-HP-2Ow6lX916y7uf_9Zzo.

- ↑ Parker, Philip M. (December 1 2004). Morinda Citrifolia - A Medical Dictionary, Bibliography, and Annotated Research Guide to Internet References. ICON Group. ISBN 0-497-00758-4. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0497007584&id=8jVrCEmZ-HwC&dq=Morinda+citrifolia.

- ↑ Spiegel-Roy, P.; E. E. Goldschmidt (August 28 1996). The Biology of Citrus. Cambridge University Press. pp. 87–88. ISBN 0-521-33321-0. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0521333210&id=SmRJnd73dbYC&pg=PA87&lpg=PA87&dq=parthenocarpy&sig=3Guru2ZBuXpY-ZA1-0ooAZBUxqg.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Capon, Brian (February 25 2005). Botany for Gardeners. Timber Press. pp. 198–199. ISBN 0-88192-655-8. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0881926558&id=Z2s9v__6rp4C&pg=PA198&lpg=PA198&dq=coconut+dispersal&sig=o2ECHPkflL6xvh0CAjbkgmdSD1A.

- ↑ Heiser, Charles B. (April 1 2003). Weeds in My Garden: Observations on Some Misunderstood Plants. Timber Press. pp. 93–95. ISBN 0-88192-562-4. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0881925624&id=nN1ohECdSC8C&pg=PA93&lpg=PA93&dq=cocklebur&sig=pRIfunPQhPbVKoZCjjb-wj4lPx8.

- ↑ Heiser. Weeds in My Garden. pp. 162–164. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0881925624&id=nN1ohECdSC8C&pg=PA164&lpg=PA162&vq=unicorn&dq=cocklebur&sig=aRLExIV7BLqUkOD1AX7rDo0uXRM.

- ↑ Feldkamp, Susan (2002). Modern Biology. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. pp. 634. ISBN 0-88192-562-4.

- ↑ McGee. On Food and Cooking. Chapter 7: A Survey of Common Fruits. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0684800012&id=iX05JaZXRz0C&pg=PA350&lpg=PA350&sig=mRABdaXizly6iRNRVGLBT9KFNs4.

- ↑ McGee. On Food and Cooking. Chapter 6: A Survey of Common Vegetables. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0684800012&id=iX05JaZXRz0C&pg=PA300&lpg=PA299&sig=qzosecWWwdrc_oP5K8_-9VJxzYA.

- ↑ Farrell, Kenneth T. (November 1 1999). Spices, Condiments and Seasonings. Springer. pp. 17–19. ISBN 0-8342-1337-0. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0834213370&id=ehAFUhWV4QMC&pg=PA17&lpg=PA17&sig=kKUhWXqSF7EpTw70-XWN-LFega8.

- ↑ "Health benefits of fruit and vegetables are from additive and synergistic combinations of phytochemicals - Liu 78 (3): 517S - American Journal of Clinical Nutrition".

- ↑ Adams, Denise Wiles (February 1 2004). Restoring American Gardens: An Encyclopedia of Heirloom Ornamental Plants, 1640-1940. Timber Press. ISBN 0-88192-619-1. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0881926191&id=J30SOqPLMOEC&pg=PA3&lpg=PA3&sig=AniDCcooYARUBXRUWpGB1ACff88.

- ↑ Booth, Martin (June 12 1999). Opium: A History. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-20667-4. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0312206674&id=kHRyZEQ5rC4C.

- ↑ Cothran, James R. (November 1 2003). Gardens and Historic Plants of the Antebellum South. University of South Carolina Press. pp. 221. ISBN 1-57003-501-6. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=1570035016&id=s8OcSmOKeCkC&pg=PA221&lpg=PA221&dq=cockroaches&sig=BO8wcOHAKIRaQY-hOuAp-UfVO4E.

- ↑ K, Amber (December 1 2001). Candlemas: Feast of Flames. Llewellyn Worldwide. pp. 155. ISBN 0-7387-0079-7. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0738700797&id=WQL4W13EYlUC&pg=PA155&lpg=PA155&dq=bayberry&sig=eLi88WIj35Kr26iApnEUmn20ya8.

- ↑ Adrosko, Rita J. (June 1 1971). Natural Dyes and Home Dyeing: A Practical Guide with over 150 Recipes. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-22688-3. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0486226883&id=EElNckPn0FUC.

- ↑ Wake, Warren (March 13 2000). Design Paradigms: A Sourcebook for Creative Visualization. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 162–163. ISBN. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0471299766&id=j2n1BCqxWjcC&pg=PA162&lpg=PA162&sig=fl01iJ4z3HaLBm6nJ83WMLggpVk.

- ↑ "The Many Uses of the Coconut". The Coconut Museum. Retrieved on 2006-09-14.

External links

- Images of fruit development from flowers at bioimages.vanderbilt.edu

- Fruit and seed dispersal images at bioimages.vanderbilt.edu

- Fruit Facts from California Rare Fruit Growers, Inc.

- Encyclopedia Britannica 1911 on Fruit

|

|||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||