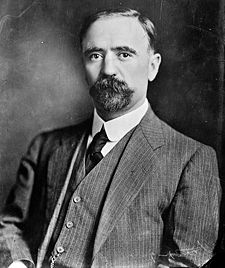

Francisco I. Madero

|

Francisco I. Madero

|

|

|

|

|

President of Mexico

|

|

|---|---|

| In office November 6 1911 – February 18 1913 |

|

| Vice President | José María Pino Suárez |

| Preceded by | Francisco León de la Barra |

| Succeeded by | Pedro Lascuráin |

|

|

|

| Born | October 30, 1873 Parras, Coahuila |

| Died | February 22, 1913 (aged 39) Mexico City |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Political party | Anti-reelectionist Party |

| Spouse | Sara Pérez |

| Religion | Spiritualist [1] |

Francisco Ignacio Madero González[2] (October 30, 1873 – February 22, 1913) was a politician, writer and revolutionary who served as President of Mexico from 1911 to 1913. As a respectable upper-class politician he supplied a center around which opposition to the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz could coalesce. However, once Díaz was deposed, the Mexican Revolution quickly spun out of Madero's control. He was deposed and executed by the Porfirista military and his aides that he neglected to replace with revolutionary supporters. His assassination was followed by the most violent period of the revolution (1913-1917) until the Constitution of 1917 and revolutionary president Venustiano Carranza achieved some degree of stability.

Early years, 1873-1903

He was born in Parras, Coahuila; the son of Francisco Indalecio Madero Hernández and Mercedes González Treviño. Some people say his middle initial, I, stood for Indalecio but according to his birth certificate it stood for Ignacio. His family was one of the richest families in Mexico: his grandfather had founded the Compaňía Industrial de Parras, which was initially involved in vineyards, cotton, and textiles, and which moved into mining, cotton mills, ranching, banking, coal, rubber, and foundries in the later part of the nineteenth century.

Madero was educated at the Jesuit college in Saltillo, but this early Catholic education had little lasting impact. Instead, his father's subscription to the magazine Revue Spirit awakened in the young Madero an interest in Spiritism, an offshoot of Spiritualism. As a young man, Madero's father sent him to business school in Paris. During his time in France, Madero made a pilgrimage to the tomb of Allan Kardec, the founder of Spiritism, and became a passionate advocate of Spiritism, soon coming to believe he was a medium. Following business school, Madero traveled to the University of California, Berkeley to study agricultural techniques and to improve his English. During his time there, he was influenced by the Theosophanist ideas of Annie Besant, which were prominent at nearby Stanford University.

In 1893, 20-year-old Madero returned to Mexico and assumed management of the Madero family's hacienda at San Pedro, Coahuila. Industrious, he installed new irrigation works, introduced American cotton, and built a soap factory and an ice factory. He also embarked on a lifelong commitment to philanthrophy. His peons were well paid and received regular medical exams; he built schools, hospitals, and community kitchens; and he paid to support orphans and give out scholarships. He also taught himself homeopathic medicine and offered medical treatments to peons personally.

Introduction to politics, 1903-1908

On April 2, 1903, Bernardo Reyes, governor of Nuevo León, violently crushed a political demonstration, an example of the increasingly authoritarian policies of president Porfirio Díaz. Madero was deeply moved and, upon the suggestion of the spirit of his deceased brother Raúl, he decided to act. Madero responded by founding the Benito Juárez Democratic Club and ran for municipal office in 1904, though he lost the election narrowly. In addition to his political activities, Madero continued his interest in Spiritism, publishing a number of articles under the pseudonym of Arjuna (a prince from the Bhagavad Gita).

In 1905, Madero became increasingly involved in opposition to the government of Porfirio Díaz. He organized political clubs and founded a political newspaper (El Demócrata) and a satirical periodical (El Mosco, "The Fly"). Madero's preferred candidate was again defeated Porfirio Díaz's preferred candidate in the 1905 governmental elections.

Beginning in 1907, Madero began to be guided by a more militant spirit, "José". At the suggestion of José and other spirits, Madero became increasingly ascetic; Madero became a vegetarian and stopped drinking alcohol at their urging. He also embarked on a speaking tour throughout Coahuila. He also used his substantial wealth to finance several more opposition newspapers.

Leader of the Anti-Reelection Movement, 1908-1909

In a 1908 interview with U.S. journalist James Creelman published in Pearson's Magazine, Porfirio Díaz said that Mexico was ready for a democracy and that the 1910 presidential election would be a free election.

Madero spent the bulk of 1908 writing a book at the directions of the spirits, which now included the spirit of Benito Juárez himself. This book, published in late 1908, was entitled La sucesión presidencial en 1910 (The Presidential Succession of 1910). The book quickly became a bestseller in Mexico. The book proclaimed that the concentration of absolute power in the hands of one man - Porfirio Díaz - for so long had made Mexico sick. Madero pointed out the irony that in 1871, Porfirio Díaz's political slogan had been "No Reelection". Madero acknowledged that Porfirio Díaz had brought peace and a measure of economic growth to Mexico. However, Madero argued that this was counterbalanced by the dramatic loss of freedom which included the brutal treatment of the Yaqui people, the repression of workers in Cananea, excessive concessions to the United States, and an unhealthy centralization of politics around the person of the president. Madero called for a return of the Liberal 1857 Constitution of Mexico. To achieve this, Madero proposed organizing a Democratic Party under the slogan Sufragio efectivo, no reelección ("Valid Suffrage, No Reelection"). Porfirio Díaz could either run oin a free election or retire.

Madero's book was well received, and many people began to call Madero the Apostle of Democracy. Madero sold off much of his property - often at a considerable loss - in order to finance anti-reelection activities throughout Mexico. He founded the Antireelection Center in Mexico City in May 1909, and soon thereafter lent his backing to the periodical El Antireeleccionista, which was run by the young lawyer/philosopher José Vasconcelos. Madero traveled throughout Mexico giving antireelectionist speeches, and everywhere he went he was greeted by crowds of thousands.

The Porfirian regime reacted by placing pressure on the Madero family's banking interests, and at one point even issued a warrant for Madero's arrest on the grounds of "unlawful transaction in rubber". Madero was not arrested, though, and in April 1910, the Antireelectionist Party met and selected Madero as their nominee for President of Mexico. Madero, worried that Porfirio Díaz would not willingly relinquish office, warned his supporters of the possibility of electoral fraud and proclaimed that "Force shall be met by force!"

Beginning of the Mexican Revolution, 1910-1911

Madero set out campaigning across the country and everywhere he was met by tens of thousands of cheering supporters. Finally, in June 1910, the Porfirian regime had him arrested in Monterrey and sent to a prison in San Luis Potosí. Approximately 5,000 other members of the Anti-Reelectionist movemnt were also jailed. Francisco Vázquez Gómez took over the nomination, but during Madero's time in jail, Díaz was "elected" as president with an electoral vote of 196 to 187.

Madero's father used his influence with the state governor and posted a bond to gain Madero the right to move about the city on horseback during the day. On October 4, 1910, Madero galloped away from his guards and took refuge with sympathizers in a nearby village. He was then smuggled across the U.S. border, hidden in a baggage car by sympathetic railway workers.

Madero set up shop in San Antonio, Texas, and quickly issued his Plan of San Luis Potosí, which had been written during his time in prison, partly with the help of Ramón López Velarde. The Plan proclaimed the elections of 1910 null and void, and called for an armed revolution to begin at 6 p.m. on November 20, 1910, against the illegitimate presidency/dictatorship of Díaz. At that point, Madero would declare himself provisional President of Mexico, and called for a general refusal to acknowledge the central government, restitution of land to villages and Indian communities, and freedom for political prisoners.

On November 20, 1910, Madero arrived at the border and planned to meet up with 400 men raised by his uncle Catarino to launch an attack on Ciudad Porfirio Díaz (modern-day Piedras Negras, Coahuila). However, his uncle showed up late and brought only ten men. As such, Madero decided to postpone the revolution. Instead he and his brother Raúl (who had been given the same name as his late brother) traveled incognito to New Orleans, Louisiana.

In February 1911 he entered Mexico and led 130 men in an attack on Casas Grandes, Chihuahua. He spent the next several months as the head of the Mexican Revolution. Madero successfully imported arms from the United States, with the American government under William Howard Taft doing little to halt the flow of arms to the Mexican revolutionaries. By April, the Revolution had spread to eighteen states, including Morelos where the leader was Emiliano Zapata.

On April 1, 1911, Porfirio Díaz claimed that he had heard the voice of the people of Mexico, replaced his cabinet, and agreed to restitution of the lands of the dispossessed. Madero did not believe Díaz and instead demanded the resignation of President Díaz and Vice President Ramón Corral. Madero then attended a meeting with the other revolutionary leaders – they agreed to a fourteen-point plan which called for pay for revolutionary soldiers; the release of political prisoners; and the right of the revolutionaries to name several members of cabinet. Madero was moderate, however. He believed that the revolutionaries should proceed cautiously so as to minimize bloodshed and should strike a deal with Díaz if possible. In May, Madero wanted a ceasefire, but his fellow revolutionaries Pascual Orozco and Francisco Villa disagreed and went ahead with an attack on Ciudad Juárez. The revolutionaries won this battle decisively and on May 21, 1911, the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez was signed.

Under the terms of the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez, Díaz and Corral agreed to resign by the end of May 1911, with Díaz's Minister of Foreign Affiars, Francisco León de la Barra, taking over as interim president solely for the purpose of calling general elections.

This first phase of the Mexican Revolution thus ended with Díaz leaving for exile in Europe at the end of May 1911. On June 7, 1911, Madero entered Mexico City in triumph where he was greeted with huge crowds shouting "Viva Madero!"

Interim Presidency of Francisco León de la Barra, May—November 1911

Although Madero had forced Porfirio Díaz from power, he did not assume the presidency in June 1911. Instead, he pursued a moderate policy, leaving Francisco León de la Barra, one of Díaz's supporters, as president. He also left in place the Congress of Mexico, which was full of candidates whom Díaz had handpicked for the 1910 election.

Madero now called for the disbanding of all revolutionary forces, arguing that the revolutionaries should henceforth proceed solely by peaceful means. In the south, revolutionary leader Emiliano Zapata was skeptical about disbanding his troops, but Madero traveled south to meet with Zapata at Cuernavaca and Cuautla, Morelos. Madero assured Zapata that the land redistribution promised in the Plan of San Luis Potosí would be carried out when Madero became president.

However, in Madero's absence, several landowners from Zapata's state of Morelos had appealed to President de la Barra and the Congress to restore their lands which had been seized by revolutionaries. They spread exaggerated stories of atrocities committed by Zapata's troops, calling Zapata the "Atilla of the South." De la Barra and the Congress therefore decided to send troops under Victoriano Huerta to suppress Zapata's troops. Madero once again traveled south to urge Zapata to disband his troops peacefully, but Zapata refused on the grounds that Huerta's troops were advancing on Yautepec de Zaragoza. Zapata's suspicions proved accurate as Huerta's troops moved violently into Yautepec de Zaragoza. Madero wrote to De la Barra, saying that Huerta's actions were unjustified and recommending that Zapata's demands be met. However, when he left the south, he had achieved nothing. However, he promised the Zapatistas that once he became president, things would change. Most Zapatistas had grown suspicious of Madero, however.

Before becoming president, Madero published another book, this one under the pseudonym of Bhima (one of Arjuna's brothers in the Mahābhārata) called a Spiritualist Manual.

Madero as President of Mexico, November 1911 — February 1913

Madero became president in November 1911, and, intending to reconcile the nation, appointed a cabinet which included many of Porfirio Díaz's supporters. However, Madero was unable to seek the reconciliation he desired since conservative Porfirians had managed to get themselves organized during the interim presidency of Francisco León de la Barra and now mounted a sustained and effective opposition to Madero's reform program. Conservative Porfirians in the Senate refused to pass the reforms he advocated. At the same time, several of Madero's allies denounced him for being overly reconciliatory with the Porfirians and with not moving aggressively forward with reforms: thus, on November 25, 1911, Emiliano Zapata issued his Plan of Ayala, denouncing Madero for being uninterested in pursuing land reform.

After years of censorship, Mexican newspapers took the opportunity of their newfound freedom of the press to roundly criticize Madero's performance as president. Gustavo A. Madero, the president's brother, remarked "the newspapers bite the hand that took off their muzzle." Francisco Madero refused the recommendation of some of his advisors that he bring back censorship, however.

The press was particularly criticial of Madero's handling of three rebellions that broke out against his rule shortly after he became president:

(1) In December 1911, Bernardo Reyes (the popular general whom Porfirio Díaz had sent to Europe on a diplomatic mission because Díaz worried that Reyes was going to challenge him for the presidency) launched a rebellion in Nuevo León, where he had previously served as governor. Reyes' rebellion lasted only eleven days before Reyes surrendered at Linares, Nuevo León and was sent to a prison in Mexico City.

(2) In March 1912, Madero's former general Pascual Orozco, who was personally resentful of how Madero had treated him, launched a rebellion in Chihuahua with the financial backing of Luis Terrazas, a former Governor of Chihuahua who was the largest landowner in Mexico. Madero despatched troops under General José González Salas to put down the rebellion, but they were initially defeated by Orozco's troops. General José González Salas committed suicide and Victoriano Huerta assumed control of the federalist forces. Huerta was more successful, defeating Orozco's troops in three major battles and forcing Orozco to flee to the United States in September 1912.

Relations between Huerta and Madero grew strained during the course of this campaign when Pancho Villa, the commander of the División del Norte, refused orders from General Huerta. Huerta ordered Villa's execution, but Madero commuted the sentence and Villa was set free. Angry at Madero's commutation of Villa's sentence, Huerta, after a long night of drinking, mused about reaching an agreement with Orozco and together deposing Madero as president. When Mexico's Minister of War learned of General Huerta's comments, he stripped Huerta of his command, but Madero intervened and restored Huerta to command.

(3) In October 1912, Félix Díaz (nephew of Porfirio Díaz) launched a rebellion in Veracruz, "to reclaim the honor of the army trampled by Madero." This rebellion was quickly crushed and Félix Díaz was imprisoned. Madero was prepared to have Félix Díaz executed, but the Supreme Court of Mexico declared that Félix Díaz would be imprisoned, but not executed.

Besides managing rebellions, Madero did have a number of accomplishments during his presidency:

- He created the Department of Labor; introduced regulation of the labor practices in the textile industry; and oversaw the creation of the Casa del Obrero Mundial ("House of the World Worker"), an organization with anarcho-syndicalist connections, that would play a major role in the subsequent Mexican labor movement.

- Although not as radical as the Zapatistas would have liked, Madero did introduce some agrarian reforms, such as a reorgnization of rural credit and the creation of agricultural stations.

- He launched an infrastructure program, building schools, railroads, and new highways.

- He introduced new taxation on foreign oil companies.

Fall and execution

In early 1913 Victoriano Huerta, the commander of the armed forces conspired with Félix Díaz (Porfirio Díaz's nephew), Bernardo Reyes, and US Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson against Madero, which culminated in a ten-day siege of La Ciudadela known as La decena tragica (the Tragic Ten Days). Madero accepted Huerta's "protection" from the Diaz/Reyes forces, only to be betrayed by Huerta and arrested. Madero's brother and advisor Gustavo A. Madero was kidnapped off the street, tortured, and killed. Following Huerta's coup d'état on February 18, 1913, Madero was forced to resign. After a 45 minute term of office, Pedro Lascuráin was replaced by Huerta who took over the Presidency later that day. Francisco Madero was shot four days later, aged 39. The Huerta government claimed that bodyguards were forced to shoot Madero and Vice President Pino Suárez, during a failed rescue attempt by Madero's supporters. This story has been challenged with general incredulity. Pino Suárez was the last vice president of México.

References

- ↑ Krauze, Enrique. Mexico: Biography of Power. A History of Modern Mexico, 1810-1996. HarperCollins Publishers Inc. New York, 1997. Page 246-247, 264

- ↑ His middle name was "Ignacio" or, in the archaic spelling recorded on his baptismal record, "Ygnacio". The popular belief that he was "Francisco Indalecio" appears to have no historical sustent. "Madero era (Y)gnacio, no Indalecio". El Universal (21 November 2008). Retrieved on 21 November 2008.

Miscellany

| Preceded by Francisco León de la Barra For Porfirio Díaz |

President of Mexico 1911–1913 |

Succeeded by Pedro Lascuráin For Victoriano Huerta |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||