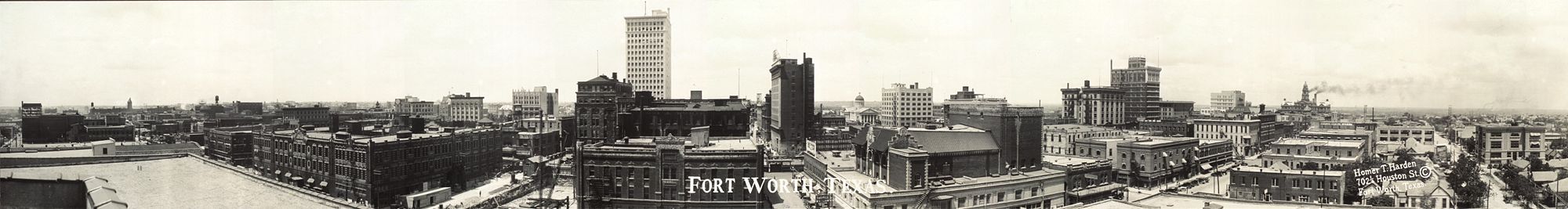

Fort Worth, Texas

| City of Fort Worth | |||

|

|||

|

|||

| Nickname(s): Cowtown[1]; Panther City[1] "Funkytown" | |||

| Motto: "Where the West begins"[1] | |||

|

|||

| Coordinates: | |||

| Country | United States | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| State | Texas | ||

| Counties | Tarrant, Denton, Wise | ||

| Government | |||

| - Mayor | Michael J. Moncrief | ||

| Area | |||

| - City | 298.9 sq mi (774.1 km²) | ||

| - Land | 292.5 sq mi (757.7 km²) | ||

| - Water | 6.3 sq mi (16.4 km²) | ||

| Elevation | 653 ft (216 m) | ||

| Population (2007)[2] | |||

| - City | 681,818 (17th) | ||

| - Density | 1,827.8/sq mi (705.7/km²) | ||

| - Metro | 6,145,037 | ||

| - Demonym | Fort Worthians | ||

| Time zone | CST (UTC-6) | ||

| - Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) | ||

| Area code(s) | 682, 817 | ||

| FIPS code | 48-27000[3] | ||

| GNIS feature ID | 1380947[4] | ||

| Website: fortworthgov.org | |||

Fort Worth is the fifth-largest city in the state of Texas and the seventeenth-largest city in the United States.[5] Situated in North Texas and a cultural gateway into the American West, Fort Worth covers nearly 300 square miles (780 km2) in Tarrant and Denton counties, serving as the county seat for Tarrant County. As of the 2007 U.S. Census estimate, Fort Worth had a population of 681,818.[2] Its population has now reached 702,850, according to new estimates released by the North Central Texas Council of Governments. The city is the second-largest cultural and economic center of the Dallas–Fort Worth–Arlington metropolitan area (commonly called the Metroplex). Fort Worth and the surrounding Metroplex area offer numerous business opportunities and a wide array of attractions.

Established originally in 1849 as a protective Army outpost situated on a bluff overlooking the Trinity River, the city of Fort Worth today still embraces its western heritage and traditional architecture and design.

Contents |

History

By the 1840s scores of Americans from the East coast were moving westward. As Ranchers and Settlers from the Eastern states made their way into the area, Native Americans retreated from the North Texas frontier. Meanwhile, tensions mounted between the Republic of Texas and its southern neighbor, Mexico, since Texas' victory over Mexico at San Jacinto in 1836.

The Mexican War

Texas remained an independent Republic for nine years prior to being annexed as the 28th state on December 29, 1845. Less than three months later on March 24, 1846, an American Army commanded by General Zachary Taylor was encamped along the northern banks of the Rio Grande, directly across the river from Mexican soldiers. Within a month, hostilities commenced and a large body of Mexican cavalrymen attacked a patrol of dragoons (soldiers trained to fight on foot, but who transport themselves on horseback) on April 23, 1846. Declaring, "American blood had been shed on American soil", President Polk addressed Congress, who declared war on Mexico.

Major General William Jenkins Worth (1794-1849) was second in command to General Zachary Taylor at the opening of the Mexican-American War in 1846. Born in Hudson, NY, Worth was a tall and commanding figure said to be the best horseman and handsomest man in the Army. He was of a manly, generous nature, and possessed talents that would have won him distinction on any field of action. While leading his troops, Worth himself personally planted the first American flag on the Rio Grande.

Under General Taylor, Worth conducted negotiations for Mexico's surrender of Matamoros and was entrusted with the assault on the Bishop's Palace in Monterrey, Mexico. The assault on the Bishop's Palace was a hazardous undertaking. Worth and his troops managed to drag their cannon and ammunition over adverse terrain and up sheer cliff faces while under constant heavy enemy fire. Worth passed from post to post during the entire action on horseback escaping personal injury and losing a minimal number of his soldiers.

Worth played a critical role in the capture of Puebla (Mexico's second largest city in 1846) and was one of the first to enter the city of Mexico, where he personally cut down the Mexican flag that waved over the National Palace. At the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848, Worth was placed in command of the Department of Texas in 1849.

The Fort

In January 1849 Worth proposed a line of ten forts to mark the Western Texas frontier from Eagle Pass to the confluence of the West Fork and Clear Fork of the Trinity River. One month later Worth died from cholera. Worth was a well respected and decorated U.S. Army General at the time of his death and a hero of three wars. Fort Worth, Texas; Lake Worth, Florida; and Worth County, Georgia are named in his honor.

Upon Worth's death, General William S. Harney assumed command of the Department of Texas and ordered Major Ripley A. Arnold to find a new fort site near the West Fork and Clear Fork. On June 6, 1849, Arnold established a camp on the bank of the Trinity River and named the post Camp Worth in honor of General Worth.

In August 1849 Arnold moved the camp to the North-facing bluff which overlooked the mouth of the Clear Fork of the Trinity River. The U.S. War Department officially named the post Fort Worth on November 14, 1849.

Although Indian attacks were still a threat in the area, pioneers were already settling near the fort. E. S. Terrell (1812–1905) claimed to be the first resident of Fort Worth. [6] The fort was flooded the first year and moved to the top of the bluff where the courthouse sits today. No trace of the original fort remains.

The Town

Fort Worth went from a sleepy outpost to a bustling town when it became a stop along the legendary Chisholm Trail, the dusty path where millions of cattle were driven North to market. Fort Worth became the center of the cattle drives, and later, the ranching industry. Its location on the Old Chisholm Trail, helped establish Fort Worth as a trading and cattle center and earned it the nickname "Cowtown."

During the 1860s Fort Worth suffered from the effects of the Civil War, and Reconstruction. The population dropped as low as 175, and money, food, and supply shortages burdened the residents. Gradually, however, the town began to revive.

By 1872 Jacob Samuels, William Jesse Boaz, and William Henry Davis had opened general stores. The next year Khleber M. Van Zandt established Tidball, Van Zandt, and Company, which became Fort Worth National Bank in 1884.

In 1876 the Texas & Pacific Railway arrived in Fort Worth causing a boom and transformed the Fort Worth Stockyards into a premier cattle industry and in wholesale trade.[7] The arrival of the railroad ushered in an era of astonishing growth for Fort Worth as migrants from the devastated war-torn South continued to swell the population and small, community factories and mills yielded to larger businesses. Newly dubbed the nickname, "Queen City of the Prairies", Fort Worth supplied a regional market via the growing transportation network.

Fort Worth became the westernmost railhead and a transit point for cattle shipment. With the city's main focus being on cattle and the railroads, local businessman, Louville Niles, formed the Fort Worth Stockyards Company in 1893. Shortly thereafter, the two biggest cattle slaughtering firms at the time, Armour and Swift, both established operations in the new stockyards.

With the boom times came some problems. Fort Worth had a knack for separating cattlemen from their money. Cowboys took full advantage of their last brush with civilization before the long drive on the Chisholm Trail from Fort Worth up North to Kansas. They stocked up on provisions from local merchants, visited the colorful saloons for a bit of gambling and carousing, then galloped Northward with their cattle and whoop it up again on their way back. The town soon became home to Hell's Half Acre, the biggest collection of bars, dance halls and bawdy houses South of Dodge City, giving Fort Worth the nickname of "The Paris of the Plains."[8]

Crime was rampant and certain sections of town were off-limits for proper citizens. Shootings, knifings, muggings and brawls became a nightly occurrence. Cowboys were joined by a motley assortment of buffalo hunters, gunmen, adventurers, and crooks. As the importance of Fort Worth as a crossroads and cowtown grew, so did Hell's Half Acre.

What was originally limited to the lower end of Rusk Street (renamed Commerce Street in 1917) spread out in all directions. By 1881 the Fort Worth Democrat was complaining Hell's Half Acre covered more like two-and-half acres.

The Acre grew until it sprawled across four of the city's main North-South thoroughfares. These boundaries, which were never formally recognized, represented the maximum area covered by the Acre, around 1900. Occasionally, the Acre was also referred to as "The bloody Third Ward" after it was designated one of the city's three political wards in 1876.

Long before the Acre reached its maximum boundaries, local citizens had become alarmed at the level of crime and violence in their city. In 1876 Timothy Isaiah (Longhair Jim) Courtright was elected City Marshal with a mandate to tame the Acre's wilder activities.

Courtright cracked down on violence and general rowdiness by sometimes putting as many as 30 people in jail on a Saturday night, but allowed the gamblers to operate unmolested. After receiving information that train and stagecoach robbers, such as the Sam Bass gang, were using the Acre as a hideout, local authorities intensified law-enforcement efforts. Yet certain businessmen placed a newspaper advertisement arguing that such legal restrictions in Hell's Half Acre would curtail the legitimate business activities there.

Despite this tolerance from business, however, the cowboys began to stay away, and the businesses began to suffer. City officials muted their stand against vice. Courtright lost support of the Fort Worth Democrat and consequently lost when he ran for reelection in 1879.

Throughout the 1880s and 1890s the Acre continued to attract gunmen, highway robbers, card sharps, con men, and shady ladies, who preyed on out-of-town and local sportsmen.

At one time or another reform-minded mayors like H. S. Broiles and crusading newspaper editors like B. B. Paddock declared war on the district but with no long-term results. The Acre meant income for the city (all of it illegal) and excitement for visitors. This could possibly be why the reputation of the Acre was sometimes exaggerated by raconteurs which longtime Fort Worth residents claimed the place was never as wild as its reputation.

Suicide was responsible for more deaths than murder, and the chief victims were prostitutes, not gunmen. However much its reputation was exaggerated, the real Acre was bad enough. The newspaper claimed "it was a slow night which did not pan out a cutting or shooting scrape among its male denizens or a morphine experiment by some of its frisky females."

The loudest outcries during the periodic clean-up campaigns were against the dance halls, where men and women met, as opposed to the saloons or the gambling parlors, which were virtually all male.

A major reform campaign in the late 1880s was brought on by Mayor Broiles and County Attorney R. L. Carlock after two events. In the first of these, on February 8, 1887, Luke Short and Jim Courtright had a shootout on Main Street that left Courtright dead and Short the "King of Fort Worth Gamblers."

Although the fight did not occur in the Acre, it focused public attention on the city's underworld. A few weeks later a poor prostitute known only by the name of Sally was found murdered and nailed to an outhouse door in the Acre.

These two events, combined with the first prohibition campaign in Texas, helped to shut down the Acre's worst excesses in 1889. More than any other factor, urban growth began to improve the image of the Acre, as new businesses and homes moved into the South end of town.

Another change was the influx of black residents. Excluded from the business end of town and the nicer residential areas, Fort Worth's black citizens, who numbered some 7,000 out of a total population of 50,000 around 1900, settled into the south end of town. Though some joined in the profitable vice trade (to run, for instance, the Black Elephant Saloon), many others found legitimate work and bought homes.

A third change was in the popularity and profitability of the Acre, which was no longer attracting cowboys and out-of-town visitors. Its visible population was more likely to be derelicts, hobos, and bums.

By 1900 most of the dance halls and gamblers were gone. Cheap variety shows and prostitution became the chief forms of entertainment. The Progressive era was similarly making its reformist mark felt in districts like the Acre all over the country.

In 1911 Rev. J. Frank Norris launched an offensive against racetrack gambling in the Baptist Standard and used the pulpit of the First Baptist Church to attack vice and prostitution. Norris used the Acre to scourge the leadership of Fort Worth. When he began to link certain Fort Worth businessmen with property in the Acre and announce their names from his pulpit, the battle heated up.

On February 4, 1912, Norris's church was burned to the ground; that evening his enemies tossed a bundle of burning oiled rags onto his porch, but the fire was extinguished and caused minimal damage. A month later the arsonists succeeded in burning down the parsonage.

In a sensational trial lasting a month, Norris was charged with perjury and arson in connection with the two fires. He was acquitted, but his continued attacks on the Acre accomplished little until 1917. A new city administration and the federal government, which was eyeing Fort Worth as a potential site for a major military training camp, joined forces with the Baptist preacher to bring down the curtain on the Acre finally.

The police department compiled statistics showing that 50 percent of the violent crime in Fort Worth occurred in the Acre, a shocking confirmation of long-held suspicions. After Camp Bowie was located on the outskirts of Fort Worth in the summer of 1917, martial law was brought to bear against prostitutes and barkeepers of the Acre. Fines and stiff jail sentences curtailed their activities. By the time Norris held a mock funeral parade to "bury John Barleycorn" in 1919, the Acre had become a part of Fort Worth history. The name, nevertheless, continued to be used for three decades thereafter to refer to the depressed lower end of Fort Worth.[9]

2000s

On March 28th 2000 at 6:15 PM, an F3 tornado smashed through downtown, tearing many buildings into shreds and scrap metal. One of the hardest hit structures was Bank One Tower. The 'Plywood Skyscraper' and later 'Tin Can Tower' awaited demolition for several years, deemed as unsafe and too cost-prohibitive to revive. It has since been converted to upscale condominiums and officially renamed 'The Tower'. It caused severe damage to one prominent 70s-era high-rise extensive enough to elicit rejected proposals for demolition.[10]

When oil began to gush in West Texas, Fort Worth was at the center of the wheeling and dealing. In July 2007, advances in horizontal drilling technology made vast natural gas reserves in the Barnett Shale available directly under the city, helping many residents receive royalty checks for their mineral rights.[11] Today the City of Fort Worth and many residents are dealing with the benefits and issues associated with the natural gas reserves under ground.[12] [13]

Fort Worth was the fastest growing large city in the United States from 2000-2006 [14] and was voted one of "America’s Most Livable Communities."[15]

Diamond Hill is located in the northern part of Fort Worth. It is a low income neighborhood that is predominant with Mexican, and Mexican-American families.

Geography and Climate

Fort Worth is located in northern Texas and the Southwest, and the South portion of the United States. The DFW Metroplex is the hub of the North Texas region. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 298.9 square miles (774.1 km²). 292.5 square miles (757.7 km²) of it is land and 6.3 square miles (16.4 km²) of it (2.12%) is water.

A large storage dam was built in 1913 on the West Fork of the Trinity River, 7 miles (10 km) from the city, with a storage capacity of 30 billion US gallons (110,000,000 m³) of water. The lake formed by this dam is known as Lake Worth. The cost of the dam was nearly US$1,500,000 - a handsome sum at the time.

Climate

Fort Worth has a humid subtropical climate according to the Köppen climate classification system. The hottest month of the year is July, when the average high temperature is 97 °F (36 °C), and overnight low temperatures average 72 °F (23 °C), giving an average temperature of 84 °F (29 °C)[16]. The coldest month of the year is January, when the average high temperature is 55 °F (13 °C), and low temperatures average 31 °F (-1 °C)[16]. The average temperature in January is 43 °F (6 °C)[16]. The highest temperature ever recorded in Fort Worth is 111 °F (44 °C), on July 26, 1954[17]. The coldest temperature ever recorded in Fort Worth is -6 °F (-21 °C), on December 24, 1989[18] Because of its position in North Texas, Fort Worth is very susceptible to supercells, which produce tornadoes. (See recent history above.)

The average annual precipitation for Fort Worth is 34.01 inches (863.8 mm)[16]. The wettest month of the year is May, when 4.58 inches (116.3 mm) of precipitation falls.[16]. The driest month of the year is January, when only 1.70 inches (43.2 mm) of precipitation falls[16] The average annual snowfall in Fort Worth is very light, only 2.6 inches (66.0 mm)[19]

Demographics

| Historical populations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 6,663 |

|

|

| 1890 | 23,076 | 246.3% | |

| 1900 | 26,668 | 15.6% | |

| 1910 | 73,312 | 174.9% | |

| 1920 | 106,482 | 45.2% | |

| 1930 | 163,447 | 53.5% | |

| 1940 | 177,662 | 8.7% | |

| 1950 | 278,778 | 56.9% | |

| 1960 | 356,268 | 27.8% | |

| 1970 | 393,476 | 10.4% | |

| 1980 | 385,164 | −2.1% | |

| 1990 | 447,619 | 16.2% | |

| 2000 | 534,694 | 19.5% | |

| Est. 2007 | 686,850 | 28.5% | |

As of the census[3] of 2000, there were 534,694 people, 195,078 households, and 127,581 families residing in the city. The July 2004 census estimates have placed Fort Worth in the top 20 most populous cities (# 19) in the U.S. with the population at 604,538.[20] Fort Worth is also in the top 5 cities with the largest numerical increase from July 1, 2003 to July 1, 2004 with 17,872 more people or a 3.1% increase. [21] The population density was 1,827.8 people per square mile (705.7/km²). There were 211,035 housing units at an average density of 721.4/sq mi (278.5/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 59.69% White, 20.26% Black or African American, 0.59% Native American, 2.64% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, 14.05% from other races, and 2.72% from two or more races. 29.81% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 195,078 households out of which 34.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.8% were married couples living together, 14.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.6% are classified as non-families by the United States Census Bureau. Of 195,078 households, 9,599 are unmarried partner households: 8,202 heterosexual, 676 same-sex male, and 721 same-sex female households.

28.6% of all households were made up of individuals and 7.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.67 and the average family size was 3.33.

In the city the population was spread out with 28.3% under the age of 18, 11.3% from 18 to 24, 32.7% from 25 to 44, 18.2% from 45 to 64, and 9.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31 years. For every 100 females there were 97.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $37,074, and the median income for a family was $42,939. Males had a median income of $31,663 versus $25,917 for females. The per capita income for the city was $18,800. About 12.7% of families and 15.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 21.4% of those under age 18 and 11.7% of those age 65 or over.

Fort Worth stands as the ninth-safest U.S. city among those with a population over 500,000 in 2006. [22]

- See also: People of Fort Worth

Cityscape

List of neighborhoods in Fort Worth, Texas

Architecture

Downtown is mainly known for its art deco style buildings. The Tarrant County Courthouse was created in the American Beaux Arts Design, which was modeled after the Texas Capitol Building, and most buildings around Sundance Square have preserved their early 20th century facades.

Downtown

Downtown Fort Worth.

- Sundance Square - Fort Worth's downtown has Sundance Square is an 8 block entertainment district for the city. The Square has brick-pavers, sidewalk cafes, and landscaping which set it apart. Restaurants, nightclubs, boutiques, museums, live theaters, cineplex movie theaters, and art galleries are along the Square.

- Fort Worth Water Gardens - A 4.3 acre/1.74 ha contemporary park, designed by architect Philip Johnson, that features three unique pools of water offering a calming and cooling oasis for downtown patrons. The gardens were used in the finale of the 1976 sci-fi film Logan's Run. (In mid-2004 the Water Gardens had to be closed due to several drownings. It has reopened after preventive measures have been installed.)

- Fort Worth Convention Center - Includes an 11,200 seat multi-purpose arena.

- Bass Performance Hall - Bass Hall is the permanent home to the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra, Texas Ballet Theater, Fort Worth Opera, and the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition and Cliburn Concerts.

- Tarrant County Courthouse stands at the north end of Main Street. It has been remodeled over the years and the exterior was used frequently in Walker, Texas Ranger.

- The Omni Fort Worth Hotel will be the first new downtown hotel construction in over 20 years. Its former estimated height was around 547 ft (167 m), but it has been down-sized by 100 feet. The tower will still have 34 floors, but now it will be 447 ft. tall.

- The Tower, formerly the Bank One Tower, was severely damaged in the March 28, 2000 tornado. It was converted into a residential tower in 2004. Before the redevelopment, The Tower was covered in plywood and metal panels, and considered to be demolished. The Tower now has a new facade and a new top feature that makes it the fourth tallest building in the city.

- City Center Development features two twin towers. One is the 38 story D.R. Horton Tower (1984), and the other is the 33 story Wells Fargo Tower (1982). From the top, they are shaped like pinwheels.

Fort Worth Stockyards Historic District

The stockyards offer a taste of the old west and the Chisholm Trail at the site of the historic cattle drives and rail access. The Old West comes alive again each year during the Fort Worth Stock Show. The District is filled with restaurants, clubs, gift shops and attractions such as daily longhorn cattle drives through the streets, historic reenactments, the Texas Cowboy Hall of Fame and Billy Bob's, the world's largest country and western music venue.

Cultural district

- The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, founded in 1892, is the oldest art museum in Texas. Its permanent collection consists of some 2,600 works of post-war art. In 2002, the museum moved into a new home designed by Japanese architect Tadao Ando.

- The Kimbell Art Museum houses works from antiquity to the 20th century. Artists represented in its holdings include Caravaggio, Fra Angelico, Picasso, Vigée-Lebrun, Matisse, Cézanne, El Greco, and Rembrandt. The museum's home was designed by American architect Louis Kahn.

- The Amon Carter Museum focuses on 19th and 20th century American artists. It houses an extensive collection of works by Western artists Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell, as well as an impressive collection of 30,000 exhibition-quality photographs. It also includes works by Alexander Calder, Thomas Cole, Stuart Davis, Thomas Eakins, Winslow Homer, Georgia O'Keeffe, John Singer Sargent, and Alfred Stieglitz. American architect Philip Johnson designed the museum's home, including its expansion.

- The National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame is the only museum in the world that is solely dedicated to honoring women of the American West who have demonstrated extraordinary courage and pioneer spirit in their trail blazing efforts.

- The Fort Worth Museum of Science and History - One of the largest Science and History Museums in the Southwest. It includes the Noble Planetarium and the Omni Theater.

- Will Rogers Memorial Center - a multi-purpose entertainment complex and world-class equestrian center housed under 45 acres (180,000 m2) of roof spread over 85 acres (340,000 m2) in the heart of the Fort Worth Cultural District. Each year approximately 800,000 people attend the three week event known as the Southwestern Exposition and Livestock Show, formerly called the Fort Worth Stock Show & Rodeo.

- Casa Mañana - The nation's first theater designed for musicals "in the round". A controversial renovation completed in 2003 turned the once unique "House of Tomorrow" into a traditional theater and abandoned the round design. The building's unique silver dome remains.

- Museum Place is an 11-acre, mixed-use development in construction that includes ground level retail, office space, and residential space. The main buildings in this development will be an eight-story brick and glass low rise, a modernized flatiron style building and a new post office that will feature damaged metal from the 2000 tornado as an art display.

- 7th Street is the main street for the cultural district, since it will feature the Museum Place development, the existing residential So7 and Montgomery Plaza, West 7th (another mixed-use development which will feature office, residential, retail, hotel, and a movie theater), and there are even talks of a streetcar route in the near future.

Parks district

- Fort Worth Zoo - Ranked one of the top 10 best zoos in the United States by Family Fun magazine

- Fort Worth Botanic Garden - The oldest botanic garden in Texas, with 21 specialty gardens and over 2,500 species of plants.

- Fort Worth Japanese Garden

- Log Cabin Village - A collection of authentic Texas log cabins dating from the 1850s.

- Trinity Park - A large park along the Trinity River that includes part of the Trinity Trails system.

Texas Christian University

- Texas Christian University - Fort Worth's most prominent university, founded in 1873 by Addison & Randolph Clark as "AddRan Male & Female College". It is the largest university affiliated with the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), though the denomination does not own or operate the school, rather, the school-church partnership is based on a common heritage and shared values. The university became known as "Texas Christian University" in 1902 and was the first co-educational institution in the US's southwest region. The school now occupies approximately 325 acres (1.32 km2) right in the heart of Fort Worth. Originally, only 50 acres (200,000 m2) of land were ceded to the Clark brothers; at the time, the land was dubbed "Hell's Half Acre" due to the red-light businesses that were predominant in the area. In 1895 the plot of land was given free of charge, along with $200,000, to entice the brothers to permanently settle their educational institution in Fort Worth. Over $1.5 million dollars are exclusively endowed each year to ensure the upkeep of the university, which sits as a pristine green/flowered landscape in the middle of the urban surroundings of Fort Worth.

Uptown / Trinity

The Tarrant Regional Water District, City of Fort Worth, Tarrant County, Streams & Valleys Inc, and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers are cooperating in an effort to develop an area north of "downtown" as "uptown" along the Trinity River. This plan promotes a large mixed use development adjacent to the central city area of Fort Worth, with a goal to prevent urban sprawl by promoting the growth of a healthy, vibrant urban core. The Trinity River Vision lays the groundwork to enable Fort Worth's central business district to double in size over the next 40 years. [6]

Other

- The Tandy Center Subway, based in the Tandy Center (now known as City Place), operated in Fort Worth from 1963 to 2002. The 0.7 mile (1 km) long subway was the only privately operated subway in the United States.

- Trinity Trails - A network of over 35 miles (56 km) of pedestrian trails along the Trinity River.

- United States Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) - Federal Reserve notes (United States paper currency) are printed at the bureau's facilities in north Fort Worth.

- United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) - Home to the US Army Engineer Fort Worth District District Office.

- Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base Fort Worth, formerly known as Carswell Air Force Base, is a major military installation in west Fort Worth and a major contributor to the local economy.

- Logan's Run, a 1976 science fiction film directed by Michael Anderson and starring Michael York was shot largely in Fort Worth, including locations such as the Fort Worth Water Gardens. The Water Gardens also appear in another science-fiction film of the period, The Lathe of Heaven (1980).

Culture

Arts

Theatre

Casa Manana, Jubilee Theater, Circle Theatre, Hip Pocket Theatre

Museums

Kimbell, Amon Carter, Science and History, Texas Cowgirl, Modern, Stockyards

Music

Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra, Billy Bob's, Texas Ballet Theater, and Van Cliburn pianist competition (Bass Hall), Fort Worth Opera (Scott Theater), Live Eclectic Music (Ridglea Theater[23])

Sports and recreation

While much of Fort Worth's sports attention is focused on the Metroplex's professional sports teams, the city does have its own athletic identity. TCU competes in NCAA Division I Athletics, including the football team that is consistently ranked in the Top 25, the baseball team that has competeted in the last three NCAA Tournaments, and the women's basketball team that has competed in the last seven NCAA Tournaments. Texas Wesleyan University competes in the NAIA, and were the 2006 NAIA Div. I Men's Basketball champions and three-time National Collegiate Table Tennis Association (NCTTA) team champions (2004-2006). Fort Worth is also home to the NCAA football Bell Helicopter Armed Forces Bowl as well as four minor-league professional sports teams. One of these minor league teams, the Fort Worth Cats baseball team, were reborn in 2001. The original Cats were a very popular minor league team in Fort Worth from the 19th century (when they were called the Panthers) until 1960, when the team was merged into the Dallas Rangers.

Professional Sports Teams

| Club | Sport | Founded | League | Venue |

| Fort Worth Cats | Baseball | 2001 | AAIPBL | LaGrave Field |

| Fort Worth Flyers | Basketball | 2005 | National Basketball Association Development League | Fort Worth Convention Center |

Ft. Worth has the Texas Motor Speedway (also known as "The Great American Speedway"), a NASCAR track located north of the city in Justin, Texas, right on the Tarrant/Denton County line.

Media

Fort Worth shares its media market with the city of Dallas.

Radio stations

There are many radio stations in and around Fort Worth, with many different formats.

AM

On the AM dial, like in all other markets, political talk radio is prevalent, with WBAP 820, KLIF 570, KSKY 660, KRLD 1080, KVCE 1160 the conservative talk stations serving Fort Worth and KMNY 1360 the sole progressive talk station serving the city. KFXR 1190 is an all-news station. Sports talk can be found on KTCK 1310 ("The Ticket").

There are also several religious stations on AM in the Dallas/Fort Worth area; KHVN 970 and KGGR 1040 are the local urban gospel stations and KKGM 1630 has a Southern gospel format.

Fort Worth's Spanish speaking population is served by many stations on AM:

- KDFT 540

- KFJZ 870

- KHFX 1140

- KFLC 1270

- KTNO 1440

- KNIT 1480

- KZMP 1540

- KRVA 1600

There are also a few mixed Asian language stations serving Fort Worth:

- KHSE 700

- KTXV 890

- KZEE 1220

Other formats found on the Fort Worth AM dial are Radio Disney KMKI 620, urban KKDA 730, business talk KJSA 1120, country station KCLE 1460.

FM

Non-commercial stations serve the city fairly well. There are three college stations that can be heard--KTCU 88.7, KCBI 90.9, and KNTU 88.1, with a variety of programming. There is also local NPR station KERA 90.1, along with community station KNON 89.3.

A wide variety of commercial formats, mostly music, are on the FM dial in Fort Worth, also.

See also: .

Internet Radio Stations and Shows

When local radio station KOAI 107.5 FM, now KMVK, dropped its smooth jazz format, fans set up an internet radio station to broadcast smooth jazz for disgruntled fans.

There are a couple internet radio shows in the Fort Worth area, like DFDubbIsHot and The Broadband Brothers.

Television stations

KXAS - NBC5, KTVT - CBS11, KTXA - Independent WFAA - ABC8

Newspapers

Fort Worth has one newspaper published daily, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. The Star-Telegram is the forty-fifth most widely circulated newspaper in the United States, with a daily circulation of 210,990 and a Sunday circulation of 304,200.

The Fort Worth Weekly is an alternative weekly newspaper that serves the Dallas/Fort Worth Metroplex. The newspaper has an approximate circulation of 50,000[1]. The Fort Worth Weekly publishes every Wednesday and features, among many things, news reporting, cultural event guides, movie reviews, and editorials.

Economy

Companies Headquartered in Fort Worth, Texas USA:

Acme Brick

Airforce Airguns

Alcon (US Headquarters)

American Airlines (International Headquarters)

American IronHorse

AmeriCredit

AMR Corporation

Anchor Marketing and Design

Bell/Agusta Aerospace Company

Bell Helicopter Textron

Ben E. Keith

Burlington Northern Santa Fe Corp.

Carter & Burgess

Circle C Construction

Concussion, LLP

Consolidated Robotics

Coria Laboratories, Ltd.

Crescent Real Estate Equities Company

Dickies

Dunlaps

D. R. Horton

Enterhost

First Command Financial Planning, Inc.

Freese and Nichols

Funimation Entertainment

Galderma Laboratories (US Headquarters)

Gearhart

JKS International Salons

Justin Boot

Lockheed Martin Aeronautics

Niver Western Wear and Mesquite Shirts

RadioShack

Rahr and Sons Brewing Company

Revomatica

RPM

Pier 1 Imports

ScrewAttack Entertainment LLC

SPM Flow Control

TPG Capital, L.P.

TTI, Inc.

Will's Pro Custom Manufacturing, Inc.

XTO Energy

Transportation

- Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport - The largest aviation facility in Texas; Located between Dallas and Fort Worth in Irving, Euless, and Grapevine.

- Fort Worth Alliance Airport

- Fort Worth Meacham International Airport

- Fort Worth Spinks Airport

- Trinity Railway Express - Rail service to Dallas

- Amtrak - Heartland Flyer & Texas Eagle lines

- The T - Bus service for Fort Worth

- Trolley to downtown and historic sites by The T

- See also List of Dallas-Fort Worth area freeways

- There have been talks of a streetcar system. It should begin operation in the near future.

Fort Worth Air Route Traffic Control Center, located in the easternmost section of the city, controls air space in the area.

Education

Public schools

Most of Fort Worth is served by Fort Worth Independent School District.

Other school districts that serve portions of Fort Worth include:

- Azle Independent School District

- Birdville Independent School District

- Burleson Independent School District

- Castleberry Independent School District

- Crowley Independent School District

- Eagle Mountain-Saginaw Independent School District

- Everman Independent School District

- Hurst-Euless-Bedford Independent School District

- Keller Independent School District

- Kennedale Independent School District

- Lake Worth Independent School District

- Northwest Independent School District

- White Settlement Independent School District

The portion of Fort Worth within the Arlington Independent School District contains a wastewater plant. No residential areas are in the portion.

Private Schools

- All Saints Episcopal School (K-12)

- Azle Christian Schools (K-12) (Non-accredited)

- Bethesda Christian School (K-12)

- Colleyville Covenant Christian Academy (PreK-12)

- Covenant Classical School (K-12)

- Fort Worth Country Day School (K-12)

- Fort Worth Christian School (K-12)

- Lake Country Christian School (K-12)

- Nolan Catholic High School

- Southwest Christian School (K-12)

- Trinity Valley School (K-12)

- Temple Christian School (K-12)

- Trinity Christian Academy (K-12)

- Hill School of Fort Worth (2-12)

- Christian Life Preparatory School (K-12)

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Fort Worth oversees several Catholic elementary and middle schools.[24]

- The Katie Brown School for Special Needs (PreK-12)

- The Nazarene Christian Academy (K-12)

- Calvary Christian Academy - (K-12) (Accredited)

- Pinnacle Academy of the arts-(k-12)(No tuition)(charter school)

Institutes of Higher Education

- Further information: List of colleges and universities in Fort Worth, Texas

- Texas Christian University

- Brite Divinity School (TCU)

- College of Saint Thomas More

- Tarrant County College

- Texas Wesleyan University School of Law

- Texas Wesleyan University

- Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary

- University of North Texas Health Science Center at Fort Worth

- University of Texas at Arlington, Fort Worth campus

Sister cities

Fort Worth is a part of the Sister Cities International program and maintains cultural and economic exchange programs with its 7 sister cities.

Reggio Emilia, Italy (1985)

Reggio Emilia, Italy (1985) Nagaoka, Niigata, Japan (1987)

Nagaoka, Niigata, Japan (1987) Trier, Germany (1987)

Trier, Germany (1987) Bandung, Indonesia (1990)

Bandung, Indonesia (1990) Budapest, Hungary (1990)

Budapest, Hungary (1990) Toluca, Mexico (1998)

Toluca, Mexico (1998) Mbabane, Swaziland (2004)

Mbabane, Swaziland (2004)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "From a cowtown to "Cowtown"". Retrieved on 2008-07-18.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Table 1: Annual Estimates of the Population for Incorporated Places Over 100,000, Ranked by July 1, 2007 Population: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2007" (CSV). 2007 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division (2008-07-10). Retrieved on 2008-07-10.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved on 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey (2007-10-25). Retrieved on 2008-01-31.

- ↑ McCann, Ian (2008-07-10). "McKinney falls to third in rank of fastest-growing cities in U.S.", The Dallas Morning News.

- ↑ Image of E. S. Terrell with note: "E. S. Terrell. Born May 24, 1812, in Murry [sic] County, Tenn. The first white man to settle in Fort Worth, Texas in 1849. His wife was Lou Preveler. They had 7 children. In 1869 the Terrells took up residence in Young County [Texas] where he died Nov 1, 1905. He is buried at True, Texas." Image on display in historical collection at Fort Belknap, Newcastle, TX. Viewed 13 November 2008.

- ↑ Fort Worth Stockyards - History. Retrieved 20 November 2006.

- ↑ BIBLIOGRAPHY: Verana E. Berrong, History of Tarrant County: From Its Beginnings until 1875 (M.A. thesis, Texas Christian University, 1938). David Ross Copeland, Emerging Young Giant: Fort Worth, 1877-1880 (M.A. thesis, Texas Christian University, 1972). Macel D. Ezell, Progressivism in Fort Worth Politics, 1935-38 (M.A. thesis, Texas Christian University, 1963). James Farber, Fort Worth in the Civil War (Belton, Texas: Peter Hansborough Bell Press, 1960). Fort Worth Star-Telegram, October 30, 1969. Julia Kathryn Garrett, Fort Worth: A Frontier Triumph (Austin: Encino, 1972). Thomas Albert Harkins, A History of the Municipal Government of Fort Worth, Texas (M.A. thesis, Texas Christian University, 1937). Donald Alvin Henderson, Fort Worth and the Depression, 1929-33 (M.A. thesis, Texas Christian University, 1937). Delia Ann Hendricks, The History of Cattle and Oil in Tarrant County (M.A. thesis, Texas Christian University, 1969). Oliver Knight, Fort Worth, Outpost on the Trinity (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1953). Richard G. Miller, "Fort Worth and the Progressive Era: The Movement for Charter Revision, 1899-1907", in Essays on Urban America, ed. Margaret Francine Morris and Elliot West (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1975). Ruth Gregory Newman, The Industrialization of Fort Worth (M.A. thesis, North Texas State University, 1950). Buckley B. Paddock, History of Texas: Fort Worth and the Texas Northwest Edition (4 vols., Chicago: Lewis, 1922). J'Nell Pate, Livestock Legacy: The Fort Worth Stockyards, 1887-1987 (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1988). Warren H. Plasters, A History of Amusements in Fort Worth from the Beginning to 1879 (M.A. thesis, Texas Christian University, 1947). Leonard Sanders, How Fort Worth Became the Texasmost City (Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum, 1973). Robert H. Talbert, Cowtown-Metropolis: Case Study of a City's Growth and Structure (Fort Worth: Texas Christian University, 1956). Joseph C. Terrell, Reminiscences of the Early Days of Fort Worth (Fort Worth, 1906). Mack H. Williams, In Old Fort Worth: The Story of a City and Its People as Published in the News-Tribune in 1976 and 1977 (1977). Mack H. Williams, comp., The News-Tribune in Old Fort Worth (Fort Worth: News-Tribune, 1975). Janet Schmelzer.

- ↑ [[BIBLIOGRAPHY: Fort Worth Daily Democrat, April 10, 1878, April 18, 1879, July 18, 1881. Oliver Knight, Fort Worth, Outpost on the Trinity (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1953). Leonard Sanders, How Fort Worth Became the Texasmost City (Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum, 1973). Richard F. Selcer, Hell's Half Acre: The Life and Legend of a Red Light District (Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 1991). F. Stanley [Stanley F. L. Crocchiola], Jim Courtright (Denver: World, 1957). Richard F. Selcer]]

- ↑ Kenuhl.com - Personal Account of tornado. Retrieved on 17 April 2006.

- ↑ Barnett Shale - Fort Worth Texas

- ↑ In Fort Worth, gas boom fuels public outreach plan | U.S. | Reuters

- ↑ RealEstateJournal | Drilling for Natural Gas Faces Hurdle: Fort Worth

- ↑ The fastest growing U.S. cities - Jun. 28, 2007

- ↑ ""America's Most Livable: Fort Worth, TX"". Retrieved on 2007-07-19.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 Average and record temperatures and precipitation, Fort Worth, Texas, The Weather Channel. [1]

- ↑ Daily and average temperatures for July, Fort Worth, Texas, The Weather Channel. [2]

- ↑ Daily and average temperatures for December, Fort Worth, Texas, The Weather Channel. [3]

- ↑ Average annual snowfall by month, NOAA. [4]

- ↑ United States Census Bureau - Fort Worth city, Texas - Fact Sheet (2005 estimates). Retrieved 20 November 2006.

- ↑ United States Census Bureau - Port St. Lucie, Fla., is Fastest-Growing City, Census Bureau Says." Published 30 June 2005. Retrieved 20 November 2006.

- ↑ Morgan Quitno Awards. America's Safest Cities Ranked

- ↑ Ridglea Theater: [5]

- ↑ The Catholic Diocese of Fort Worth - Catholic Schools. Retrieved 20 November 2006.

External links

- City Government Website

- Convention & Visitors Bureau

- Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce

- Downtown Fort Worth news and information

- Vision FW

- Fort Worth Star-Telegram

- Fort Worth Business Press

- Fort Worth Architecture

- The Jack White Collection of Historic Fort Worth Photos

- Fort Worth Sister Cities

- Sundance Square

- Fort Worthology

- West And Clear

- Fort Worth, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online

- Historic Fort Worth materials, hosted by the Portal to Texas History

|

Dallas–Fort Worth–Arlington |

|---|---|

| Counties | Collin | Dallas | Delta | Denton | Ellis | Hunt | Johnson | Kaufman | Parker | Rockwall | Tarrant | Wise |

| over 1000 | Dallas† |

| over 500 | Fort Worth† |

| 200 - 500 | Arlington | Garland | Irving | Plano |

| 100 - 200 | Carrollton | Denton† | Frisco | Grand Prairie | McKinney† | Mesquite | Richardson |

| 50 - 100 | Allen | Euless | Flower Mound | Lewisville | Mansfield | North Richland Hills |

| 10 - 50 | Addison | Azle | Balch Springs | Bedford | Benbrook | Burleson | Cedar Hill | Cleburne† | Colleyville | Coppell | Corinth | DeSoto | Duncanville | Ennis | Farmers Branch | Forest Hill | Grapevine | Greenville† | Haltom City | Highland Village | Hurst | Keller | Lancaster | Little Elm | Rockwall† | Rowlett | Sachse | Saginaw | Seagoville | Southlake | Terrell | The Colony | University Park | Watauga | Waxahachie† | Weatherford† | White Settlement | Wylie |

| under 10 | Argyle | Blue Mound | Cockrell Hill | Combine | Cooper† | Crowley | Dalworthington Gardens | Decatur† | Edgecliff Village | Everman | Glenn Heights | Highland Park | Hutchins | Kaufman† | Kennedale | Lake Worth | Lakeside | Newark | Ovilla | Pantego | Pelican Bay | Richland Hills | River Oaks | Sansom Park | Sunnyvale | Westover Hills | Westworth Village | Willow Park | Wilmer |

| ↑ thousands of people† - County Seat. A full list of cities under 10,000 is available here. | |

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||