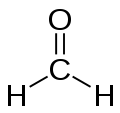

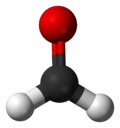

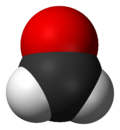

Formaldehyde

| Formaldehyde ( methanal) | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| IUPAC name | Methanal |

| Other names | formol, methyl aldehyde, methylene oxide |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 50-00-0 |

| RTECS number | LP8925000 |

| SMILES |

|

| ChemSpider ID | |

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula | CH2O |

| Molar mass | 30.03 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | colorless gas |

| Density | 1 kg·m−3, gas |

| Melting point |

-117 °C (156 K) |

| Boiling point |

-19.3 °C (253.9 K) |

| Solubility in water | > 100 g/100 ml (20 °C) |

| Structure | |

| Molecular shape | trigonal planar |

| Dipole moment | 2.33168(1) D |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Toxic, Flammable, Carcinogenic |

| NFPA 704 |

2

3

2

|

| R-phrases | R23/24/25, R34, R40, R43 |

| S-phrases | (S1/2), S26, S36/37, S39, S45, S51 |

| Flash point | -53 °C |

| Related compounds | |

| Related aldehydes | acetaldehyde |

| Related compounds | ketones |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa) Infobox references |

|

Formaldehyde (IUPAC name methanal) is a chemical compound with the formula H2CO. It is the simplest aldehyde. Formaldehyde exists in several forms aside from H2CO: the cyclic trimer trioxane and the polymer paraformaldehyde. It exists in water as the hydrate H2C(OH)2. Aqueous solutions of formaldehyde are referred to as formalin. "100%" formalin consists of a saturated solution of formaldehyde (roughly 40% by mass) in water, with a small amount of stabilizer, usually methanol to limit oxidation and polymerization. It is produced on a substantial scale of 6M tons/y. In view of its widespread use, toxicity, and volatilty, exposure to formaldehyde is significant consideration for human health.[1]

Contents |

Occurrence

Formaldehyde is an intermediate in the oxidation (or combustion) of methane as well as other carbon compounds, e.g. forest fires, in automobile exhaust, and in tobacco smoke. When produced in the atmosphere by the action of sunlight and oxygen on atmospheric methane and other hydrocarbons, it becomes part of smog.

Biological occurrence

Formaldehyde (and its oligomers and hydrates) are rarely encountered in living organisms. Methanogenesis proceeds via the equivalent of formaldehyde, but this one-carbon species is masked as a methylene group in methanopterin. Formaldehyde is the primary cause of methanol's toxicity, since methanol is metabolised into toxic formaldehyde by alcohol dehydrogenase. Formaldehyde is converted to formic acid in the body, leading to a rise in blood acidity (acidosis).

Interstellar formaldehyde

Formaldehyde was first discovered in instellar space in 1969 by L. Snyder et al. using the National Radio Astronomy Observatory. H2CO was detected by means of the 111 - 110 ground state rotational transition at 4830 Mhz [2].

Formaldehyde was the first polyatomic organic molecule detected in the interstellar medium and since its initial detection has been observed in many regions of the galaxy [3]. The isotopic ratio of [12C]/[13C] was determined to be about or less than 50% in the galactic disk [4]. Formaldehyde has been used to map out kinematic features of dark clouds located near Gould's Belt of local bright stars [5]. In 2007, the first H2CO 6 cm maser flare was detected[6]. It was a short duration outburst in IRAS 18566 + 0408 that produced a line profile consistent with the superposition of two Gaussian components, which leads to the belief that an event outside the maser gas triggered simultaneous flares at two different locations[6]. Although this was the first maser flare detected, H2 masers have been observed since 1974 by Downes and Wilson in NGC 7538[7]. Unlike OH, H2O, and CH3OH, only five galactic star forming regions have associated formaldehyde maser emission, which has only been observed through the 110 → 111 transition[7].

Synthesis and industrial production

Formaldehyde was first reported by the Russian chemist Aleksandr Butlerov (1828-1886), but was conclusively identified by August Wilhelm von Hofmann.[8]

Formaldehyde is produced industrially by the catalytic oxidation of methanol. The most common catalysts are silver metal or a mixture of an iron and molybdenum or vanadium oxides. In the more commonly used FORMOX process methanol and oxygen react at ca 250-400 °C in presence of iron oxide in combination with molybdenum and/or vanadium to produce formaldehyde according to the chemical equation:[1]

The silver-based catalyst is usually operated at a higher temperature, about 650 °C. Two chemical reactions on it simultaneously produce formaldehyde: that shown above and the dehydrogenation reaction:

- CH3OH → H2CO + H2

Formalin can be produced on a smaller scale using a whole range of other methods including conversion from ethanol instead of the normally-fed methanol feedstock. Such methods are of less commercial importance.

In principle formaldehyde could be generated by oxidation of methane, but this route is not industrially viable because the formaldehyde is more easily oxidized than methane.[1]

Organic chemistry

Formaldehyde is a building block in the synthesis of many other compounds of specialized and industrial significance. It exhibits most of the chemical properties of other aldehydes but is more reactive. For example it is more readily oxidized by atmospheric oxygen to formic acid (formic acid is found in ppm levels in commercial formaldehyde). Formaldehyde is a good electrophile, participating in electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions with aromatic compounds, and can undergo electrophilic addition reactions with alkenes and aromatics. Formaldehyde undergoes a Cannizzaro reaction in the presence of basic catalysts to produce formic acid and methanol.

Examples of organic synthetic applications

Condensation with acetaldehyde affords pentaerythritol, a chemical necessary in synthesizing PETN, a high explosive.[9] Condensation with phenols gives phenol-formaldehyde resins. With 4-substituted phenols one obtains calixarenes.[10]

When combined with hydrogen sulfide it forms trithiane.[11]

- 3 CH2O + 3 H2S → (CH2S)3 + 3 H2O

Industrial applications

Formaldehyde is a common building block for the synthesis of more complex compounds and materials. In approximate order of decreasing consumption, products generated from formaldehyde include urea formaldehyde resin, melamine resin, phenol formaldehyde resin, polyoxymethylene plastics, 1,4-butanediol, and methylene diphenyl diisocyanate.[1]

When reacted with phenol, urea, or melamine formaldehyde produces, respectively, hard thermoset phenol formaldehyde resin, urea formaldehyde resin, and melamine resin, which are commonly used in permanent adhesives such as those used in plywood or carpeting. It is used as the wet-strength resin added to sanitary paper products such as (listed in increasing concentrations injected into the paper machine headstock chest) facial tissue, table napkins, and roll towels. They are also foamed to make insulation, or cast into moulded products. Production of formaldehyde resins accounts for more than half of formaldehyde consumption.

Formaldehyde is also a precursor to polyfunctional alcohols such as pentaerythritol, which is used to make paints and explosives. Other formaldehyde derivatives include methylene diphenyl diisocyanate, an important component in polyurethane paints and foams, and hexamine, which is used in phenol-formaldehyde resins as well as the explosive RDX.

The textile industry uses formaldehyde-based resins as finishers to make fabrics crease-resistant.[12]

It is also used as an ingredient by some shampoo manufacturers.

Miscellaneous applications

Formaldehyde is a common component of many niche uses. Formaldehyde, along with 18 M (concentrated) sulfuric acid (the entire solution often called the Marquis reagent)[13], is used as an MDMA "testing kit" by such groups as Dancesafe as well as MDMA consumers. The solution alone cannot verify the presence of MDMA but reacts with many other chemicals that the MDMA tablet itself may be adulterated with. The reaction itself produces colors that correlate with these components.

As a disinfectant and biocide

An aqueous solution of formaldehyde can be useful as a disinfectant as it kills most bacteria and fungi (including their spores). It is also used as a preservative in vaccines. Formaldehyde solutions are applied topically in medicine to dry the skin, such as in the treatment of warts. Many aquarists use formaldehyde as a treatment for the parasite ichthyophthirius.[14]

Formaldehyde preserves or fixes tissue or cells by irreversibly cross-linking primary amino groups in proteins with other nearby nitrogen atoms in protein or DNA through a -CH2- linkage. This is exploited in ChIP-on-chip transcriptomics experiments. Formaldehyde is also used as a denaturing agent in RNA gel electrophoresis, preventing RNA from forming secondary structures.

In photography

Formaldehyde is still used in low concentrations for process C-41 (color negative film) stabilizer in the final wash step, as well as in the process E-6 pre-bleach step, to obviate the need for it in the final wash.

Tissue fixative and embalming agent

Formaldehyde solutions are used as a fixative for microscopy and histology. Formaldehyde-based solutions are also used in embalming to disinfect and temporarily preserve human and animal remains. It is the ability of formaldehyde to fix the tissue that produces the tell-tale firmness of flesh in an embalmed body. Several European countries restrict the use of formaldehyde, including the import of formaldehyde-treated products and embalming, and the European Union is considering a complete ban on formaldehyde usage (including embalming), subject to a review of List 4B of the Technical Annex to the Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the Evaluation of the Active Substances of Plant Protection Products by the European Commission Services. Countries with a strong tradition of embalming corpses, such as Ireland and other colder-weather countries, have raised concerns. The European Union decided on September 22, 2007 to ban Formaldehyde use throughout Europe due to its carcinogenic properties.[15]

Safety

Occupational exposure to formaldehyde by inhalation is mainly from three types of sources: thermal or chemical decomposition of formaldehyde-based resins, formaldehyde emission from aqueous solutions (for example, embalming fluids), and the production of formaldehyde resulting from the combustion of a variety of organic compounds (for example, exhaust gases). Formaldehyde can be toxic, allergenic, and carcinogenic.[16] Because formaldehyde resins are used in many construction materials it is one of the more common indoor air pollutants.[17] At concentrations above 3 ppb in air formaldehyde can irritate the eyes and mucous membranes, resulting in watery eyes. Formaldehyde inhaled at this concentration may cause headaches, a burning sensation in the throat, and difficulty breathing, as well as triggering or aggravating asthma symptoms.[18][19]

Formaldehyde is classified as a probable human carcinogen by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has determined that there is "sufficient evidence" that occupational exposure to formaldehyde causes nasopharyngeal cancer in humans. [20] The United States Environmental Protection Agency USEPA allows no more than 0.016 ppm formaldehyde in the air in new buildings constructed for that agency.[21] On April 11th, 2008, FEMA announced that all trailers purchased by that agency in the future must meet the same standard.[22]

Formaldehyde can cause allergies and is part of the standard patch test series. People with formaldehyde allergy are advised to avoid formaldehyde releasers as well (e.g., Quaternium-15, imidazolidinyl urea, and diazolidinyl urea).[23] Formaldehyde has been banned in cosmetics in both Sweden and Japan.

FEMA trailer incidents

Hurricane Katrina & Rita

In the U.S. the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) provided travel trailers and mobile homes starting in 2006 for habitation by residents of the U.S. gulf coast displaced by Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita. Some of the people who moved into the trailers complained of breathing difficulties, nosebleeds, and persistent headaches. Formaldehyde-catalyzed resins were used in the production of these homes.

The United States Centers For Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) performed indoor air quality testing for formaldehyde [24] in some of the units. On Thursday, February 14, 2008 the CDC announced that potentially hazardous levels of formaldehyde were found in many of the travel trailers and mobile homes provided by the agency.[25][26] The CDC's preliminary evaluation of a scientifically established random sample of 519 travel trailers and mobile homes tested between Dec. 21, 2007 and Jan. 23, 2008 (2+ years after manufacture) showed average levels of formaldehyde in all units of about 77 parts per billion (ppb). Long-term exposure to levels in this range can be linked to an increased risk of cancer and, at levels above this range, there can also be a risk of respiratory illness. These levels are higher than expected in indoor air, where levels are commonly in the range of 10-20 ppb, and are higher than the Agency for Toxic Substance Disease Registry (ATSDR, division of the CDC) Minimal Risk Level (MRL) of 8 ppb [27]. Levels measured ranged from 3 ppb to 590 ppb.[28]

The Federal Emergency Management Agency, which requested the testing by the CDC, said it would work aggressively to relocate all residents of the temporary housing as soon as possible. Lawsuits are being filed against FEMA as a result of the exposures.[29]

Iowa Floods of 2008

Also in the U.S., problems arose in trailers again provided by FEMA to residents displaced by the Iowa floods of 2008. A couple months after moving to the trailers, occupants reported violent coughing, headaches, as well as Asthma, Bronchitis, and other problems. Tests showed that in some trailers levels of formaldehyde exceeded the limits recommended by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and American Lung Association.[30].[31] The associated publicity has resulted in additional testing to begin in November.[32]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 G. Reuss, W. Disteldorf, A. O. Gamer, A. Hilt, “Formaldehyde” in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry Wiley-VCH, 2005, Weinheim.

- ↑ Snyder, L. E., Buhl, D., Zuckerman, B., & Palmer, P. 1969, Phys. Rev. Lett., 22, 679

- ↑ Zuckerman, B.; Buhl, D.; Palmer, P.; Snyder, L. E. 1970, Astrophysical Journal, 160, 485

- ↑ Henkel, C.; Guesten, R.; Gardner, F. F. 1985, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 143, 148

- ↑ Sandqvist, A.; Tomboulides, H.; Lindblad, P. O. 1988, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 205, 225

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Araya, E. _et al_. 2007, Astrophysical Journal, 654, L95

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hoffman, I. M.; Goss, W. M.; Palmer, P. 2007, Astrophysical Journal, 654, 971

- ↑ J Read, Text-Book of Organic Chemistry, G Bell & Sons, London, 1935

- ↑ H. B. J. Schurink (1941). "Pentaerythritol". Org. Synth. 1: 425; Coll. Vol. 1.

- ↑ Gutsche, C. D.; Iqbal, M. (1993). "p-tert-Butylcalix[4]arene". Org. Synth.; Coll. Vol. 8: 75.

- ↑ Bost, R. W.; Constable, E. W. (1943). "sym-Trithiane". Org. Synth.; Coll. Vol. 2: 610.

- ↑ FORMALDEHYDE IN CLOTHING AND OTHER TEXTILES

- ↑ DanceSafe: testing kit info

- ↑ University of Florida - Use of Formalin to Control Fish Parasites http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/VM061

- ↑ Formaldehyde Ban set for 22 Sept 2007

- ↑ IARC Press Release June 2004, http://www.iarc.fr/ENG/Press_Releases/archives/pr153a.html

- ↑ Indoor Air Pollution in California, Final Report, California Air Resources Board (2005) http://www.arb.ca.gov/research/indoor/ab1173/finalreport.htm, at pages 65 – 70.

- ↑ http://www.oehha.ca.gov/air/chronic_rels/AllChrels.html California Office Of Health Hazard Assessment

- ↑ Symptoms of Low-Level Formaldehyde Exposures, Health Canada, http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/iyh-vsv/environ/formaldehyde_e.html

- ↑ http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol88/volume88.pdf "Formaldehyde".

- ↑ Testing for Indoor Air Quality, Baseline IAQ, and Materials, http://www.epa.gov/rtp/new-bldg/environmental/s_01445.htm

- ↑ In the US, FEMA limits formaldehyde in trailers, Boston.com, referenced 9/4/2008[1]

- ↑ "Formaldehyde allergy: What is formaldehyde and where is it found?". DermNet NZ.

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/nmam/pdfs/2016.pdf

- ↑ Formaldehyde Levels in FEMA-Supplied Trailers

- ↑ Mike Brunker (2006-07-25). "Are FEMA trailers ‘toxic tin cans’?", MSNBC.

- ↑ ATSDR - Minimal Risk Levels for Hazardous Substances (MRLs)

- ↑ FEMA: CDC Releases Results Of Formaldehyde Level Tests

- ↑ Suit Filed Over FEMA Trailer Toxins - washingtonpost.com

- ↑ Megan Terlecky (2008-10-24). "How We Tested for Formaldehyde", KGAN-TV.

- ↑ NIGEL DUARA (2008-10-21). "FEMA disputes formaldehyde study of Iowa trailers", Associated Press.

- ↑ Cindy Hadish (2008-10-24). "FEMA meets with mobile home residents over health concerns", Cedar Rapids Gazette.

External links

- International Chemical Safety Card 0275 (gas)

- International Chemical Safety Card 0695 (solution)

- "Formaldehyde", IARC Monograph

- Formaldehyde (gas) from the 11th Report on Carcinogens of the U.S. National Toxicology Program (.pdf file)

- Formaldehyde fact sheet from the Australian National Pollutant Inventory

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- Process C-41 Using KODAK FLEXICOLOR Chemicals Publication Z-131

- Formaldehyde Council

- Formaldehyde Data Sheet, ChemSub Online

- Prevention guide – Formaldehyde in the work place

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health - Formaldehyde Page