Form of government

| This article is part of the Politics series |

| Forms of government |

| List of forms of government |

|

| Politics portal |

A form of government is a term that refers to the set of political institutions by which a government of a state is organized in order to exert its powers over a Community politics.[1] Synonyms include "regime type" and "system of government". This definition holds valid even if the government is unsuccessful in exerting its power. Regardless of its qualities, a failed government is still a form of government. Churches, corporations, clubs, and other sub-national entities also have "government" forms, but in this article only the organization of states is discussed.

Nineteen states in the world do not explicitly name their government forms in their official names (the official name of Jamaica, for instance, is simply "Jamaica"), but most have an official name which identifies their form of government, or at least the form of government toward which they are striving:

- Australia, the Bahamas, and Dominica are each officially a commonwealth.

- Luxembourg is a grand duchy.

- The United Arab Emirates is a collection of Muslim states, each an emirate in its own right.

- Russia, Switzerland, and Saint Kitts and Nevis are each a federation.

- Libya is a jamahiriya

- There are 33 kingdoms in the world, but only 18 named as such. The other 15 are known as realms. Jordan is specifically titled the "Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan," while Britain is formally the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

- Andorra, Liechtenstein, and Monaco are each a principality.

- The word "republic" is used by 132 nations in their official names. Many specify a type of republic: China is titled a "people's republic; North Korea a "democratic people's republic"; Egypt and Syria "Arab republics"; Guyana a "cooperative republic"; Algeria is a "democratic and popular republic," Vietnam a "socialist republic," Sri Lanka a "democratic socialist republic.

- States which wish to emphasize that their provinces have a fair amount of autonomy from the central government may specifically state this: Germany and Nigeria are each a federal republic, Ethiopia is a federal democratic republic, the Comoros is a federal Islamic republic, and Brazil is a federative republic.

The sometimes utilized name Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia emphasizes this nation's separateness from the neighboring Greek region of the same name. Venezuela is "Bolivarian republic" which is meant to emphasize its descendance from Simon Bolivar. Uruguay is "Oriental republic" which hints to it being successor of the Provincia Oriental del Río de la Plata. Government ideology is also a common signifier appended to "republic". Besides the Comoros, four other nations specifically dictate that they are Islamic republics. Asian nations influenced by Maoism may emphasize their belief system by specifying the People as a whole in their official names: Laos is a people's democratic republic, and Bangladesh and China are people's republics. Vietnam is a socialist republic. Finally, Tanzania emphasizes the cohesion of its state as a united republic.

- Eleven nations simply refer to themselves as states, but a handful specify what kind of state. Micronesia is made up of federated states, Papua New Guinea and Samoa emphasize that they are independent states, while the United States of America and the United Mexican States are made up of constituent states.

- Brunei and Oman are sultanates.

- Burma simply states that it is a union.

Contents |

Attributes of government

Beyond official typologies it is important to think about regime types by looking at the general attributes of the forms of government [2]:

- Traditional/premodern (clan/kinship-based, chiefdom) or modern (bureaucracies)

- Personalistic or impersonal

- Autocracy (totalitarianism or authoritarianism), oligarchy, or democracy

- Elective or hereditary

- Direct or indirect elections (United States Electoral College)

- Secular, state religion with religious toleration, theocratic

- Republic or monarchy

- Constitutional monarchy or absolute monarchy

- Majority government or coalition government

- Single-member district or proportional representation

- Party system: Non-partisan, single-party; dominant-party; two-party; multi-party

- Separation of powers (executive, legislative, or judicial) or no separation of powers

- Parliamentary, presidential, or semi-presidential

- Single or multiple executive (Switzerland has seven executives of the Swiss Federal Council, France has a dual executive of the Prime Minister and President; the United States has a single executive, the President)

- Composition of the legislative power (rubber stamp or active)

- Unicameralism or bicameralism (much more rarely, tricameralism and tetracameralism)

- Number of coalitions or party-appointed legislators in assemblies

- Confederation, federation, or unitary

- Voting system:

- Plurality ("first past the post")

- Majoritarian (50 percent plus one), including two-round (runoff) elections

- Supermajoritarian (from 55 to 75 percent) - Senate cloture rules, entrenched clauses, absolute majorities

- Unanimity - (100 percent) - corporate governance for board of directors

- Type of economic system

- Prevalent ideologies and cultures

- Strong institutional capacity or weak capacity

- Legitimate or illegitimate (Communist Romania)

- De facto (effective control) or De jure (nominal control) of government

- Sovereign, semi-sovereign, not sovereign

Other empirical and conceptual problems

On the surface, identifying a form of government appears to be easy. Most would say that the United States is a democratic republic while the former Soviet Union was a totalitarian state. However, as Kopstein and Lichbach (2005:4) argue, defining regimes is tricky. Defining a form of government is especially problematic when trying to identify those elements that are essential to that form. There appears to be a disparity between being able to identify a form of government and identifying the necessary characteristics of that form. For example, in trying to identify the essential characteristics of a democracy, one might say "elections." However, both citizens of the former Soviet Union and citizens of the United States voted for candidates to public office in their respective states. The problem with such a comparison is that most people are not likely to accept it because it does not comport with their sense of reality. Since most people are not going to accept an evaluation that makes the former Soviet Union as democratic as the United States, the usefulness of the concept is undermined. In political science, it has long been a goal to create a typology or taxonomy of polities, as typologies of political systems are not obvious [3]. It is especially important in the political science fields of comparative politics and international relations. One important example of a book which attempts to do so is Robert Dahl's Polyarchy (Yale University Press (1971)).

One approach is to further elaborate on the nature of the characteristics found within each regime. In the example of the United States and the Soviet Union, both did conduct elections, and yet one important difference between these two regimes is that the USSR had a single-party system, with all other parties being outlawed. In contrast, the United States effectively has a bipartisan system with political parties being regulated, but not forbidden. A system generally seen as a representative democracy (for instance Canada, India and the United States) may also include measures providing for: a degree of direct democracy in the form of referendums and for deliberative democracy in the form of the extensive processes required for constitutional amendment.

Another complication is that a number of political systems originate as socio-economic movements and are then carried into governments by specific parties naming themselves after those movements. Experience with those movements in power, and the strong ties they may have to particular forms of government, can cause them to be considered as forms of government in themselves. Some examples are as follows:

- Perhaps the most widely cited example of such a phenomenon is the communist movement. This is an example of where the resulting political systems may diverge from the original socio-economic ideologies from which they developed. This may mean that adherents of the ideologies are actually opposed to the political systems commonly associated with them. For example, activists describing themselves as Trotskyists or communists are often opposed to the communist states of the 20th century.

- Islamism is also often included on a list of movements that have deep implications for the form of government. Indeed, many nations in the Islamic world use the term Islamic in the name of the state. However, these governments in practice exploit a range of different mechanisms of power (for example debt and appeals to nationalism). This means that there is no single form of government that could be described as “Islamic” government. Islam as a political movement is therefore better seen as a loose grouping of related political practices rather than a single, coherent political movement.

- The basic principles of many other popular movements have deep implications for the form of government those movements support and would introduce if they came to power. For example, bioregional democracy is a pillar of green politics.

See also

- Civics

- Comparative government

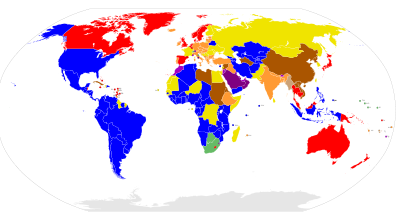

- List of countries by system of government

- List of forms of government

- List of European Union member states by political system

References

- ↑ http://assets.cambridge.org/052184/3162/excerpt/0521843162_excerpt.pdf Kopstein and Lichbach, 2005

- ↑ Regime Types

- ↑ Lewellen, Ted C. Political Anthropology: An Introduction Third Edition. Praeger Publishers; 3rd edition (November 30, 2003)

Further reading

- Boix, Carles (2003). Democracy and Redistribution. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Bunce, Valerie. 2003. “Rethinking Recent Democratization: Lessons from the Postcommunist Experience.” World Politics 55(2):167-192.

- Colomer, Josep M. (2003). Political Institutions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dahl, Robert Polyarchy Yale University Press (1971

- Heritage, Andrew, Editor-in-Chief. 2000. World Desk Reference

- Lijphart, Arend (1977). Democracy in Plural Societies: A Comparative Exploration. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Linz, Juan. 2000. Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

- Linz, Juan, and Stepan, Alfred. 1996. Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: Southernn Europe, South America, and Post-Communist Europe. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

- Lichbach, Mark and Alan Zukerman, eds. 1997. Comparative Politics: Rationality, Culture, and Structure, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Luebbert, Gregory M. 1987. “Social Foundations of Political Order in Interwar Europe,” World Politics 39, 4.

- Moore, Barrington, Jr. 1966. Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World. Cambridge: Beacon Press, ch. 7-9.

- Comparative politics : interests, identities, and institutions in a changing global order/edited by Jeffrey Kopstein, Mark Lichbach, 2nd ed, Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- O’Donnell, Guillermo. 1970. Modernization and Bureaucratic-Authoritarianism. Berkeley: University of California.

- O’Donnell, Guillermo, Schmitter, Philippe C., and Whitehead, Laurence, eds., Transitions from Authoritarian Rule: comparative Perspectives. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Przeworski, Adam. 1992. Democracy and the Market: Political and Economic Reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Przeworski, Adam, Alvarez, Michael, Cheibub, Jose, and Limongi, Fernando. 2000. Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well Being in the World, 1950-1990. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Shugart, Mathhew and John M. Carey, Presidents and Assemblies: Constitutional Design and Electoral Dynamics, New York, Cambridge Univ. Press, 1992.

- Taagepera, Rein and Matthew Shugart. 1989. Seats and votes: The effects and determinants of electoral systems, Yale Univ. Press.jimmy