Forced disappearance

A forced disappearance occurs when an organization forces a person to vanish from public view, either by murder or by simple sequestration. The victim is first kidnapped, then illegally detained in concentration camps, often tortured, and finally executed and the corpse hidden. In Spanish and Portuguese, "disappeared people" are called desaparecidos, a term which specifically refers to the mostly South American victims of state terrorism during the 1970s and the 1980s, in particular concerning Operation Condor.

According to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, which entered into force on July 1, 2002, when committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, "forced disappearances" qualify as a crime against humanity, which thus cannot be subject to statute of limitation.

Typically, a murder will be surreptitious, with the body disposed of in such a way as to never be found. The person apparently vanishes. The party committing the murder has deniability, as there is no body to show that the victim is actually dead. Furthermore, the perpetrators of disappearance often go to great lengths to obscure or eliminate all mention of the disappeared, by altering the historical record and encouraging the silence of surviving relatives. In Chile and Argentina, for example, the infamous "death flights" were used during Operation Condor by the military juntas to dispose of the victims' bodies at sea. Since the bodies couldn't be found decades later, those responsible for human right violations claimed that the statute of limitations impeded any trial. However, in Chile, judge Juan Guzmán Tapia would create, by jurisprudence, the felony of "permanent sequestration": he argued that since the bodies couldn't be found, the statute of limitations couldn't be applied since the sequestration continued and was still in effect. Juan Guzmán thus ensured the possibility of bringing to trial some of the Chilean military men involved, even though the amnesty law of 1978 continues to apply, since the democratic government has not yet abrogated it.

Contents |

Linguistic considerations

In the case of forced disappearance the word disappear, which is properly an intransitive verb, is often used transitively. Victims, who are those who have disappeared, or the disappeared, are said to have been disappeared, rather than the more usual have disappeared. The perpetrators have disappeared them, rather than made them disappear. Of course in these circumstances both the formal expressions "was made to disappear" or "was caused to disappear" and the informal transitive usage are euphemisms: these people have presumably been tortured and murdered; they have indeed disappeared, but forever.

Similar considerations apply in Spanish. Instead of (él) desapareció (he disappeared), we have (ellos) lo desaparecieron (they disappeared him).

Both the English noun phrase the disappeared and the Spanish los desaparecidos are often understood nowadays to refer to victims of state terror.

The term desaparecidos and associated verb and English expressions originally referred to South America's "Dirty War", particularly in Chile, Argentina and Uruguay, which cooperated, together with other dictatorships, in Operation Condor. However, the term is coming into more general use.

Metaphorical use

The idea of forced disappearance has created the new usage described above. The use of disappeared in this sense is now sometimes extended to political or social commentary not involving crimes against the person. Upper mid-level government officials who lose their positions due to unpopularity with the public or their superiors are metaphorically said to have been disappeared (e.g., former US FEMA Director Michael D. Brown, former US Secretary of the Treasury Paul O'Neill), meaning that official sources cease to refer to them and ignore their previous existence. Embarrassing documents that are claimed to have been lost in transit or are otherwise unavailable are also said to have been "disappeared."

Well known incidents

NGOs such as Amnesty International or Human Rights Watch record in their annual report the number of cases of forced disappearance.

Algeria

During the Algerian Civil War, which began in 1992 as Islamist guerrillas attacked the military government which had annulled an Islamist electoral victory, thousands of people were forcibly disappeared. Disappearances continued up to the late 1990s, but thereafter dropped off sharply with the decline in violence from c:a 1997. Some of the disappeared were kidnapped or killed by the guerrillas, but others are presumed to have been taken by state security services. This latter group has become the most controversial. Their exact numbers remain disputed, but the government has acknowledged a figure of just over 6,000 disappeared, now presumed dead. Opposition sources claim the real number is closer to 17,000. (The war claimed a total toll of 150-200,000 deaths). In 2005, a controversial amnesty law was approved in a referendum, among other things granting financial compensation to families of disappeared, but also effectively ended the police investigations into the crimes.[1]

Chechnya (Russia)

Estimated 5,000 people disappeared in Chechnya since 1999, most of them in the early years of the Second Chechen War. Most of them are believed to be buried in several dozen mass graves.

Iraq

At least tens of thousands people disappeared under the regime of Saddam Hussein, many of them during Operation Anfal.

Islamic Republic of Iran

Following the Iran student riots in 1999, more than 70 students disappeared. In addition to an estimated 1,200-1,400 detained, the "whereabouts and condition" of five students named by Human Rights Watch remained unknown.[2] The United Nations has also reported other disappearances.[3] After each manifestation, from teacher union to women right activists, at least some disappearances are expected.[4][5] Dissident writers have been the target of disappearances.[6]

Nazi Germany

During World War II, Nazi Germany set up secret police forces including branches of the Gestapo in occupied countries, which they used to hunt down known or suspected dissidents or partisans. This tactic was given the name Nacht und Nebel (Night and Fog) to describe those who disappeared after being arrested by Nazi forces without any warning. The Nazis also applied this policy against political opponents within Germany. Most victims were killed on the spot or sent to concentration camps, with the full expectation that they would be killed.

Northern Ireland's "Troubles"

In "The Troubles" of Northern Ireland people were disappeared. Well-known cases include Jean McConville, who was abducted and killed by the Provisional IRA in 1972 (she had been accused of being an informer) - her body was discovered by accident in 2003; and Columba McVeigh, a seventeen year old Catholic who was killed by the IRA in 1975 on suspicion of being an informer.[7] Cases of this nature are being investigated by the Independent Commission for the Location of Victims' Remains.

Operation Condor and Argentina's Dirty War

| Operation Condor |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Histories of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil (1960s), Chile, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay · 1973 Chilean coup d'état |

| Events |

| Dirty War · National Reorganization Process · Operation Colombo · Operation Charly Operation Gladio · Night of the Pencils · Operativo Independencia · 1973 Ezeiza massacre · Massacre of Margarita Belén · Death flights · Desaparecidos |

| Dictators |

| Augusto Pinochet · Alfredo Stroessner · Jorge Rafael Videla · Leopoldo Galtieri · Jorge Anaya · Basilio Lami Dozo |

| Notable operatives and responsible people |

| Stefano Delle Chiaie · Michael Townley · Luis Posada Carriles · Virgilio Paz Romero · Orlando Bosch · Hugo Campos Hermida · José López Rega · Paul Schäfer · Alfredo Astiz |

| Responsible organizations |

| DINA · Caravan of Death · Batallón de Inteligencia 601 · CORU · DISIP · SNI/ABIN · SOA · Triple A · SISMI |

| Places |

| Esmeralda (BE-43) · Estadio Nacional de Chile · Villa Grimaldi · Colonia Dignidad · ESMA |

| Laws |

| Ley de Punto Final Ley de Obediencia Debida |

| Archives and reports |

| Archives of Terror · Rettig Report · Valech Report · National Security Archive |

| Reactions |

| CONADEP · Trial of the Juntas · Augusto Pinochet's arrest and trial · Madres de la Plaza de Mayo · Montoneros · MIR |

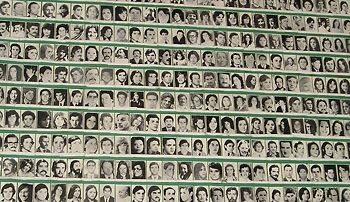

During Argentina's "Dirty War" and operation Condor, political dissidents were heavily drugged and then thrown alive out of airplanes far out over the Atlantic Ocean, leaving no trace of their passing. Without any dead bodies, the government could deny they had been killed. People murdered in this way (and in others) are today referred to as "the disappeared" (los desaparecidos), and this is where the modern use of the term derives. An activist group called "Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo", formed by mothers of those victims of the dictatorship, were the inspiration for a song by Irish rock band U2, Mothers of the Disappeared (see also the Valech Report for Chile). Rubén Blades also composed a song called "Desaperecidos" in honor of those political dissidents. Boris Weisfeiler is thought to have disappeared near Colonia Dignidad, a German colony founded by anti-Communist Paul Schäfer in Chile which was used as a detention center by the DINA, the secret police.

The phrase was infamously recognized by Argentinian de facto President, General Videla, who said in a press conference during the Military Government he commanded in Argentina: "They are neither dead nor alive, they disappeared".

It is thought that in Argentina between 1976 and 1983 up to 30,000 people (9,000 verified named cases according to the official report by the CONADEP)[8] were subject to forced disappearance under the military junta that was in power. From information collected from military officers involved in the so-called "Dirty War" it is known that many victims were sedated and dumped from airplanes into the Río de la Plata (today these are called vuelos de la muerte, death flights). Other people were held in torture and detention centres, the most notorious one being the Navy's Mechanics Training School (ESMA) in the Núñez district of Buenos Aires.

Many women gave birth in captivity; they were then killed and their children given illegally in adoption to families and friends of military or police personnel. The task of locating these children and restoring their lost identity has been going on since the restoration of democracy in 1983. Legal proceedings were taken against those involved in these actions even while amnesties were in place for other crimes by the military since appropriating children from their mothers is a crime that lies outside the scope of military procedures, and thus also outside any kind of amnesty law or pardon that implies orders in a military context.

Soviet Union

|

| Vanished commissar: Nikolai Yezhov retouched |

The damnatio memoriae method of disappearance was practiced in the Soviet Union. When an important political figure was convicted, e.g., during the Great Purge, artists would retouch them out of photographs; books, records, and histories would be recalled, rewritten, or reenacted; pictures, busts, and statues would be taken down; people would be discouraged from talking about them; and the government would never mention them again. They were made never to have existed, in a manner parodied as the Ministry of Truth in George Orwell's novel Nineteen Eighty-Four. Notable examples range from prominent Russian revolutionaries who took part in the Russian Revolution but disagreed with Bolsheviks, to some of the most devoted Stalinists (e.g., Nikolai Yezhov) who fell into disfavor.

- For details of one example of such practice, read: Great Soviet Encyclopedia#Damnatio memoriae

Disappearance was a special clause in the penal sentence: "without the right to correspondence". In many cases this phrase hid the execution of the convicted, although the sentence may have been for, e.g., "10 years of labor camps without the right to correspondence". The fate of tens of thousands people only became known after the 1950s destalinization.

Western Sahara

There are many well documented cases about people kidnapped and murdered by Morocco's Government[9] Since Morocco invaded Western Sahara in 1975, somewhere around 1,500 suspected Polisario-sympathizers and other independence activists have been abducted.[9] In several cases, whole families were taken in retaliation for Sahrawis joining the Polisario forces in Tindouf, Algeria. The disappeared were subjected to severe torture, and held in secret detention camps such as Tazmamart and Carcel Negra where many died due to poor conditions or lack of medical treatment. In the early 90s, hundreds of Sahrawis were released and others proclaimed dead after the signing of a cease-fire between Morocco and the Polisario, but approximately 500 remain unaccounted for. Many of the released prisoners have since been re-arrested for protesting their detention.[9]

In February 2007 Morocco has signed an international convention protecting people from forced disappearance, [10] but the Moroccoan legislation allows the assassination of Sahrawis, and usually let the killers free, like in the Hamdi Lembarki case, in 2005.[11] The Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón has declared the competence of the Spanish jurisdiction in the Hispano-Sahrawi disappearances and there have been charges brought against some Moroccan military heads, most of them currently in power as of 2007[update].

Disappearances in human rights law

In international human rights law, disappearances at the hand of the state have been codified as enforced or forced disappearances. For example, the Rome Statute establishing the International Criminal Court defines enforced disappearance as a crime against humanity, and the practice is specifically addressed by the OAS's Inter-American Convention on Forced Disappearance of Persons.

The International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, adopted by the UN General Assembly on December 20 2006, also states that the widespread or systematic practice of enforced disappearances constitutes a crime against humanity. Crucially, it gives victims' families the right to seek reparations and to demand the truth about the disappearance of their loved ones. The Convention provides for the right not to be subjected to enforced disappearance as well as the right for the relatives of the disappeared person to know the truth. The Convention contains several provisions concerning prevention, investigation and sanctioning of this crime, as well as the rights of victims and their relatives and the wrongful removal of children born during their captivity. The Convention further sets forth the obligation of international cooperation, both in the suppression of the practice and in dealing with humanitarian aspects related to the crime. The Convention establishes a Committee on Enforced Disappearances, which will be charged with important and innovative functions of monitoring and protection at the international level. Currently an international campaign of the International Coalition against Enforced Disappearances is working towards universal ratification of the Convention.

Disappearances work on two levels: not only do they silence opponents and critics who have disappeared, but they also create uncertainty and fear in the wider community, silencing others who would oppose and criticise. Disappearances entail the violation of many fundamental human rights. For the disappeared person, these include the right to liberty, the right to personal security and humane treatment (including freedom from torture), the right to a fair trial, to legal counsel, and to equal protection under the law, the right of presumption of innocence etc. Their families, who often spend the rest of their lives searching for information on the disappeared, are also victims.

Data on human rights violation and state repression

There is currently a wide variety of databases available which attempt to measure, in a rigorous fashion exactly what governments do against those within their territorial jurisdiction. The list below was created and maintained by Prof. Christian Davenport at the University of Maryland. These efforts vary with regard to the particular form of human rights violation they are concerned with, the source employed for the data collection as well as the spatial and temporal domain of interest.

Global coverage

- "CIRI Human Rights Data Project, 1981-2006". by Profs David Cingranelli and David Richards

- "Freedom in the World, 1976-2006" by Freedom House

- "Genocide & Politicide, 1955-2005" by Prof. Barbara Harff and the Political Instability Task Force

- "Political Terror Scale, 1976-2006 by Prof. Mark Gibney

- "Worldwide Atrocities Dataset, 1995-2007 by the Political Instability Task Force/KEDS

- "World Freedom Atlas, 1990-2006" - Mapping Program by Prof. Zachary Forest Johnson

Regional coverage

- "European Protest and Coercion, 1980-1995" by Prof. Ron Francisco

Selective coverage of state repression

- "The Kansas Event Data System (KEDS)" by Profs. Deborah “Misty” Gerner and Phill Schrodt

- "Intranational Political Interactions Project, 1979-1992" by Profs. David Davis and Will Moore

- "Minorities at Risk, 1945-2006" by the Center for International Development and Conflict Management

Country coverage of state repression

- "Guatemala, 1960-1996" by the International Center for Human Rights Research

- "Kosovo, 1999" by the Human Rights Data Analysis Group - Benetech

- "Rwanda, 1994" by Profs. Christian Davenport and Allan Stam - The Genodynamics Project

- "Sierra Leone, 1991-2000" by the Human Rights Data Analysis Group - Benetech

- "Timor-Leste, 1974-1999" by the Human Rights Data Analysis Group - Benetech

- "United States vs. the Black Panthers, 1967-1973" by Prof. Christian Davenport - "Rashomon and Repression"

- "United States vs. the Republic of New Africa, 1968-1974 by Prof. Christian Davenport - "Out on the Inside"

Film

- Imagining Argentina (2003). Directed by Christopher Hampton.

- The Official Story (1985). Directed by Luis Puenzo.

- Missing (1982). Directed by Costa-Gavras.

- Disappear (short-film) (2008). Set on the day of a school shooting. Directed by amateur director David Spraker.

- In an episode of The X-Files from season nine, John Doggett awakens in a Mexican town with no knowledge of who he is (EP: John Doe).

- Rendition (film) (2007). Directed by Gavin Hood.

Literature

- V for Vendetta. Written by Alan Moore, Illustrated by David Lloyd.

- Nineteen Eighty-Four. Written by George Orwell.

- A Tale of Two Cities. Written by Charles Dickens.

- Catch-22. Written by Joseph Heller.

- When Darkness Falls. Written by James Grippando (2007).

- La muerte y la doncella (English Title: Death and the Maiden). Written by Ariel Dorfman.

- Información para extranjeros (English Title: Information for Foreginers). Written by Griselda Gambaro.

- "Graffiti" from the collection Queremos tanto a Glenda. Written by Julio Cortázar.

Popular music

- "Desaparecidos" appeared on the album Voice of America by Little Steven & the Disciples of Soul.

- "Desapariciones" by Rubén Blades (also covered by Los Fabulosos Cadillacs and Maná).

- "Mothers of the Disappeared" appeared on the album The Joshua Tree, by U2.

- "They Dance Alone (Cueca Solo)" appeared on the album ...Nothing Like the Sun by Sting.

References

- ↑ Algeria: Amnesty Law Risks Legalizing Impunity for Crimes Against Humanity (Human Rights Watch, 14-4-2005)

- ↑ New Arrests And "Disappearances" Of Iranian Students

- ↑ UN experts urge Iran to observe human rights norms in case of dead journalist

- ↑ BBC report

- ↑ BBC News | MIDDLE EAST | Clashes at Iran teachers protest

- ↑ WAN protests disappearances in Iran

- ↑ BBC NEWS | Northern Ireland | Church issues Disappeared appeal

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 (Spanish) AFADEPRESA Asocciation of families of Saharaui Convicts and Disappearances: Disappearances

- ↑ [2][3]

- ↑ La legislación marroquí ampara el asesinato de saharauis.

External links

- International Coalition against Enforced Disappearances

- Enforced Disappearances Information Exchange Center

- Desaparecidos.org (in English & Spanish)

- "The Commissar Vanishes" — Nikolai Yezhov airbrushed out of a picture with Stalin;

- The International Commission on Missing Persons

- Kausfiles, February 14, 2004 (includes example of metaphorical usage of the term in U.S. political discourse)

- The Vanished Gallery

- University of Ulster's CAIN website page on The Disappeared

- Groups list 39 "disappeared" in U.S. war on terror

See also

- Argentine Dirty War

- Black sites

- Comisión Nacional sobre la Desaparición de Personas

- Command responsibility

- Damnatio memoriae

- Extraordinary rendition

- Ghost detainee

- Gukurahundi

- International Day of the Disappeared

- Missing person

- Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, an Argentine activist group formed by mothers of desaparecidos

- North Korean abductions of Japanese

- Nacht und Nebel

- Secret police

- Arbitrary arrest and detention

- Selective assassination

- Unperson

- Unexplained disappearances

- List of people who have disappeared