Flat tax

| Public finance |

|---|

|

| Taxation |

| Income tax · Payroll tax CGT · Stamp duty · LVT Sales tax · VAT · Flat tax Tax, tariff and trade Tax haven |

| Tax incidence |

| Tax rate · Proportional tax Progressive tax · Regressive tax Tax advantage |

|

Taxation by country

Tax rates around the world |

| Economic policy |

| Monetary policy Central bank • Money supply Gold standard |

| Fiscal policy Spending • Deficit • Debt |

| Policy-mix |

| Trade policy Tariff • Trade agreement |

| Finance |

| Financial market Financial market participants Corporate · Personal Public · Regulation |

| Banking |

| Fractional-reserve · Full-reserve Free banking · Islamic banking |

| • project |

A flat tax (short for flat rate tax) is a tax system with a constant tax rate.[1] Usually the term flat tax would refer to household income (and sometimes corporate profits) being taxed at one marginal rate, in contrast with progressive taxes that may vary according to such parameters as income or usage levels.

Flat taxes that include a tax exemption for household income below a level determined by statute are not a true proportional tax, as taxable income may not equal total income. Nomenclature regarding flat taxes has become increasingly lax, in that taxes that are described as flat sometimes have little to differentiate them from other tax regimes.

Contents |

Tax effects

Distribution

Tax distribution is a hotly debated aspect of flat taxes. The relative fairness hinges crucially on what tax deductions are abolished when a flat tax is introduced, and who profits the most from those deductions.

Proponents of the flat tax claim it is fairer than stepped marginal tax rates, since everybody pays the same proportion. Opponents point out first that it might not make sense for everyone to pay the same proportion when some get advantages of prosperity. Also, they note that for the state to raise the same amount of money under a flat rate tax (to the first order, that is, assuming people earn the same incomes as before) requires that the rich pay less and the poor pay more than they would under a more progressive tax system. Proponents respond to this argument by saying that second-order effects would compensate; a flat tax would remove economic disincentives and encourage economic growth, thus leading to higher incomes and more tax revenues. So taxpayers across income ranges could be paying at the same or lower rate than their old system. Economic models usually predict that flat tax will increase both output and inequality.[2][3][4]

Proponents claim that since everybody pays the same rate, it treats everyone equally and thus is fair to everyone. Opponents of the flat tax, on the other hand, claim that since the marginal value of income declines with the amount of income (the last 100 of income of a family living near poverty being considerably more valuable than the last 100 of income of a millionaire), taxing that last 100 of income the same amount despite vast differences in the marginal value of money is unfair. Many flat-tax proponents actually concede this premise since most proposals are not truly totally flat but have a threshold below which income is not taxed at all. Therefore, with the exception of flat-tax proponents who argue for no deductions and taxation of all income at one flat rate, both proponents and opponents agree in principle if not in degree with the basic premise of this concept.

However, the sizable exemptions provided under most flat tax proposals go far in restoring effective progressivity. As income for an individual increases, the exempt income becomes an ever smaller percentage of total income.

The issue of removing deductions, exemptions and special treatments is also relevant to the tax burden, if those special treatments currently benefit the better off. As an example, the tax debate in the UK has recently (2007) focused on the fact that hedge fund managers, some with multi-million pound incomes, "pay less tax than a cleaning lady"[5] (actually a lower tax rate rather than less tax), because the hedge fund manager's "income" qualifies as capital gains, taxable at 10%, rather than the cleaner's employment income taxable at 33% (22% income tax plus 11% social security charge). A flat tax that taxed both at the same rate is argued to be fairer than the current, supposedly progressive, system.

We must also consider fairness in relation to the broader concept of justice. Proponents argue that a flat tax would:

- by its greater simplicity, reduce taxes for each person, rich and poor; and

- by stimulating economic growth, produce more government revenue, directable to programs that benefit the poor.

Thus, even if a flat-rate taxation is less fair than graduated taxation as a concept, it could produce more social justice.

Administration and enforcement

A flat tax taxes all income once at its source. Hall and Rabushka (1995) includes a proposed amendment to the US Revenue Code implementing the variant of the flat tax they advocate.[6] This amendment, only a few pages long, would replace hundreds of pages of statutory language (although it is important to note that much statutory language in taxation statutes is not directed at specifying graduated tax rates; see Conflating concepts in Arguments against below). As it now stands, the USA Revenue Code is over 9 million words long and contains many loopholes, deductions, and exemptions which, advocates of flat taxes claim, render the collection of taxes and the enforcement of tax law complicated and inefficient. It is further argued that current tax law retards economic growth by distorting economic incentives, and by allowing, even encouraging, tax avoidance. With a flat tax, there are fewer incentives to create tax shelters and to engage in other forms of tax avoidance.

Under a pure flat tax without deductions, companies could simply, every period, make a single payment to the government covering the flat tax liabilities of their employees and the taxes owed on their business income.[7] For example, suppose that in a given year, ACME earns a profit of 3 million, pays 2 million in salaries, and spends an added 1 million on other expenses the IRS deems to be taxable income, such as stock options, bonuses, and certain executive privileges. Given a flat rate of 15%, ACME would then owe the IRS (3M + 2M + 1M) x0.15 = 900,000. This payment would, in one fell swoop, settle the tax liabilities of ACME's employees as well as taxes it owed by being a firm. Most employees throughout the economy would never need to interact with the IRS, as all tax owed on wages, interest, dividends, royalties, etc. would be withheld at the source. The main exceptions would be employees with incomes from personal ventures. The Economist claims that such a system would reduce the number of entities required to file returns from about 130 million individuals, households, and businesses, as at present, to a mere 8 million businesses and self-employed.

This simplicity would remain even if realized capital gains were subject to the flat tax. In that case, the law would require brokers and mutual funds to calculate the realized capital gain on all sales and redemptions. If there were a gain, 15% of the gain would be withheld and sent to the IRS. If there were a loss, the amount would be reported to the IRS, which would offset gains with losses and settle up with taxpayers at the end of the period.

Under a flat tax, the government's cost of processing tax returns would become much smaller, and the relevant tax bodies could be abolished or massively downsized. The people freed from working in administering taxes will then be employed in jobs that are more productive. If combined with a provision to allow for negative taxation, the flat tax itself can be implemented in an even simpler way. In addition, such a tax reduces the cost of welfare administration significantly.

It is invariably argued that a flat tax will greatly simplify tax compliance and administration. In fact, simplicity does not so much stem from the structure of tax rates (a progressive rate structure is nothing more than a look-up table filling at most one page) as from the definition of what is subject to tax. Tax simplification - getting rid of all the deductions, exemptions, and special rules added over the years - is an issue wholly separable from that of the rate structure. A nation can vastly simplify its tax code while keeping its rate structure progressive. Similarly, a nation could establish a flat tax rate while retaining inordinately complex rules defining the nature of income (such as the imputed interest rules in the US).

It is possible that a flat tax would not remain simple over time, given the realities of interest group politics. While all flat tax proposals propose to eliminate nearly all deductions and credits, some envision keeping the mortgage interest deduction and possibly some others (note that Hall and Rabushka 1995 do not).

Economic efficiency

A common approximation in economics is that the economic distortion or excess burden from a tax is proportional to the square of the tax rate.[8] A 20 percent tax rate thus causes four times the excess burden or deadweight loss of a 10 percent tax, since it is twice the rate. Broadly speaking, this means that a low uniform rate on a broad tax base will be more economically efficient than a mix of high and low rates on a smaller tax base.

Revenues

Some claim the flat tax will increase tax revenues, by simplifying the tax code and removing the many loopholes corporations and the rich currently exploit to pay less tax. The Russian Federation is a claimed case in point; the real revenues from its Personal Income Tax rose by 25.2% in the first year after the Federation introduced a flat tax, followed by a 24.6% increase in the second year, and a 15.2% increase in the third year.[9] The Laffer curve predicts such an outcome, but attributes the primary reason for the greater revenue to higher levels of economic growth. The Russian example is often used as proof of this, although an IMF study in 2006 found that there was no sign "of Laffer-type behavioral responses generating revenue increases from the tax cut elements of these reforms" in Russia or in other countries.[10]

Overall structure

Some taxes other than the income tax (for example, taxes on sales and payrolls) tend to be regressive. Hence, making the income tax flat could result in a regressive overall tax structure. Under such a structure, those with lower incomes tend to pay a higher proportion of their income in total taxes than the affluent do. The fraction of household income that is a return to capital (dividends, interest, royalties, profits of unincorporated businesses) is positively correlated with total household income. Hence a flat tax limited to wages would seem to leave the wealthy better off. Modifying the tax base can change the effects. A flat tax could be targeted at income (rather than wages), which could place the tax burden equally on all earners, including those who earn income primarily from returns on investment. Tax systems could utilize a flat sales tax to target all consumption, which can be modified with rebates or exemptions to remove regressive effects (such as the proposed FairTax in the U.S.[11]).

Border adjustable

A flat tax system and income taxes overall are not inherently border-adjustable; meaning the tax component embedded into products via taxes imposed on companies (including corporate taxes and payroll taxes) are not removed when exported to a foreign country (see Effect of taxes and subsidies on price). Taxation systems such as a sales tax or value added tax can remove the tax component when goods are exported and apply the tax component on imports. Under a flat tax, domestic products are at a disadvantage to foreign products (at home and abroad). Such a system greatly impacts the global competitiveness of a country. Though, it's possible that a flat tax system could be combined with tariffs and credits to act as border adjustments (the proposed Border Tax Equity Act in the U.S. attempts this). Implementing a income tax with a border adjustment tax credit is a violation of the World Trade Organization agreement.

Race to the bottom

An argument raised by opponents of the flat tax is that corporations or wealthy persons might move to countries with lower taxes, especially in a single country context. The argument states that this would lead to a race to the bottom in which countries compete to offer ever-lower taxes for the rich, so that the rich become even richer, while the poor and middle classes, unable to financially handle relocation to another country, are left to shoulder the entire cost of all government services. A consequence would be an ever-worsening under-funding and neglect of the public sector.

Opponents of the flat tax argue that the end result of this race to the bottom is social disintegration (see also failed state), a situation from which even the richest cannot benefit. It is argued that in order to prevent this it is the responsibility of local and national governments everywhere to ensure that the rich pay a fair share of the tax burden. Concepts such as flat rate taxes are therefore said to be irresponsible at a global level, even if they may seem to grant a temporary advantage at a national level. In other words, making economic conditions too desirable in one country may have the effect of forcing other countries to compete by making their conditions equally desirable. It could however be argued that even in the absence of a flat tax, this situation in which the very wealthy relocate to lower tax jurisdictions already exists.

Around the world

Eastern Europe

Advocates of the flat tax argue that the former-Communist states of Eastern Europe have benefited from the adoption of a flat tax. Most of these nations have experienced strong economic growth of 6% and higher in recent years, some of them, particularly the Baltic countries, experience exceptional GDP growth of around 10% yearly.

- Lithuania, which levies a flat tax rate of 24% (previously 27%) on its citizens, has experienced amongst the fastest growth in Europe. Advocates of flat tax speak of this country's declining unemployment and rising standard of living. They also state that tax revenues have increased following the adoption of the flat tax, due to a subsequent decline in tax evasion and the Laffer curve effect. Others point out, however, that Lithuanian unemployment is falling at least partly as a result of mass emigration to Western Europe. The argument is that Lithuania's comparatively very low wages, on which a non-progressive flat tax is levied, combined with the possibility now to work legally in Western Europe since accession to the European Union, is forcing people to leave the country en masse. The Ministry of Labour estimated in 2004 that as many as 360,000 workers may have left the country by the end of that year, a prediction that is now thought to have been broadly accurate. The impact is already evident: in September 2004, the Lithuanian Trucking Association reported a shortage of 3,000-4,000 truck drivers. Large retail stores have also reported some difficulty in filling positions.[12] However, the emigration trend has recently stopped as enormous real wage gains in Lithuania (presumably due to the shortage of workers) have caused a return of many migrants from Western Europe. In addition to that, it is clear that countries not levying a flat tax such as Poland also temporarily faced large waves of emigration after EU membership in 2004.

- Whilst in most countries the introduction of a flat tax has coincided with strong increases in growth and tax revenue, there is no proven causal link between the two. For example, it is also possible that both are due to a third factor, such as new government that may institute other reforms along with the flat tax. A study by the IMF showed that sharp increases in Russian GDP growth and tax revenue around the time of the introduction of a 13% flat tax were not the result of the tax reform, but of a sharp increase in oil prices, strong real wage growth, and intensification in the prosecution of tax evasion.[13]

- In Estonia, which has had a 26% (24% in 2005, 23% in 2006, 22% in 2007, 21% in 2008, planned 20% in 2009, 19% in 2010, 18% in 2011) flat tax rate since 1994, studies have shown that the significant increase in tax revenue experienced was caused partly by a disproportionately rising VAT revenue.[14] Moreover, Estonia and Slovakia have high social contributions, pegged to wage levels.[14] Both matters raise questions regarding the justice of the flat tax system, and thus its long-term viability. The Estonian economist and former chairman of his country's parliamentary budget committee Olev Raju, stated in September 2005 that "income disparities are rising and calls for a progressive system of taxation are getting louder - this could put an end to the flat tax after the next election" [33]. However, this did not happen, since after the 2007 elections a right-wing coalition was formed which has stated its will to keep the flat tax in existence.

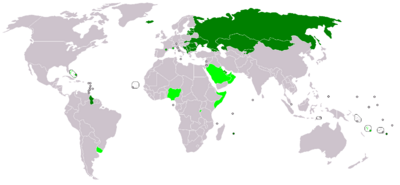

Countries that have flat tax systems

These are countries, as well as minor jurisdictions with the autonomous power to tax, that have adopted tax systems that are commonly described in the media and the professional economics literature as a flat tax.

Also:

- Transnistria, also known as Transnistrian Moldova or Pridnestrovie. [36] This is a disputed territory, but the authority that seems to have de facto government power in the area claims to levy a flat tax.

Countries reputed to have a flat tax

Hong Kong Some sources claim that Hong Kong has a flat tax,[37] though its salary tax structure has several different rates ranging from 2% to 20% after deductions. Taxes are capped at 16% of gross income, so this rate is applied to upper income returns if taxes would exceed 16% of gross otherwise.[38] Accordingly, Duncan B. Black of Media Matters for America, says "Hong Kong's 'flat tax' is better described as an 'alternative maximum tax.'" [39] Alan Reynolds of the Cato Institute similarly notes that Hong Kong's "tax on salaries is not flat but steeply progressive."[40] Hong Kong has, nevertheless, a flat profit tax regime.

Hong Kong Some sources claim that Hong Kong has a flat tax,[37] though its salary tax structure has several different rates ranging from 2% to 20% after deductions. Taxes are capped at 16% of gross income, so this rate is applied to upper income returns if taxes would exceed 16% of gross otherwise.[38] Accordingly, Duncan B. Black of Media Matters for America, says "Hong Kong's 'flat tax' is better described as an 'alternative maximum tax.'" [39] Alan Reynolds of the Cato Institute similarly notes that Hong Kong's "tax on salaries is not flat but steeply progressive."[40] Hong Kong has, nevertheless, a flat profit tax regime.

Countries considering a flat tax system

These are countries where concrete flat tax proposals are currently being considered by influential politicians or political parties.

Hungary

Hungary Poland In 2007 elections, the Civic Platform gained 41.5% of the votes, running on a 15% flat tax as one of the main points in the party program.[41]

Poland In 2007 elections, the Civic Platform gained 41.5% of the votes, running on a 15% flat tax as one of the main points in the party program.[41] Greece There are some articles from 2005 indicating that the Greek government considered a flat tax. If it is still on the table, it apparently hasn't passed yet as of February 2008.[42][43]

Greece There are some articles from 2005 indicating that the Greek government considered a flat tax. If it is still on the table, it apparently hasn't passed yet as of February 2008.[42][43] Iceland [44] [23] [45] Iceland's system differs from the Hall-Rabushka flat tax by taxing investment income and allowing numerous exceptions.[46]

Iceland [44] [23] [45] Iceland's system differs from the Hall-Rabushka flat tax by taxing investment income and allowing numerous exceptions.[46]

Recent and current proposals

Flat tax proposals have made something of a "comeback" in recent years. In the United States, former House Majority Leader Dick Armey and FreedomWorks have sought grassroots support for the flat tax (Taxpayer Choice Act). In other countries, flat tax systems have also been proposed, largely as a result of flat tax systems being introduced in several countries of the former Eastern Bloc, where it is generally thought to have been successful, although this assessment has been disputed (see below).[47] This has elicited much interest from countries such as the US, where it has gone hand in hand with a general swing towards conservatism.[48]

The countries that have recently reintroduced flat taxes have done so largely in the hope of boosting economic growth. The Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania have had flat taxes of 24%, 25% and 33% respectively with a tax exempt amount, since the mid-1990s. On 1 January2001, a 13% flat tax on personal income took effect in Russia. Ukraine followed Russia with a 13% flat tax in 2003, which later increased to 15% in 2007. Slovakia introduced a 19% flat tax on most taxes (that is, on corporate and personal income, for VAT etc., almost without exceptions) in 2004; Romania introduced a 16% flat tax on personal income and corporate profit on January 1 2005. Macedonia introduced a 12% flat tax on personal income and corporate profit on January 1 2007 and promised to cut it to 10% in 2008.[35] Albania will be implementing a 10% flat tax from 2008.[49]

In the United States, while the Federal income tax is progressive, five states — Illinois, Indiana, Massachusetts, Michigan and Pennsylvania — tax household incomes at a single rate, ranging from 3% (Illinois) to 5.3% (Massachusetts). Pennsylvania even has a pure flat tax with no zero-bracket amount.

Greece (25%) and Croatia are planning to introduce flat taxes. Paul Kirchhof, who was suggested as the next Finance minister of Germany in 2005, proposed introducing a flat tax rate of 25% in Germany as early as 2001, which sparked widespread controversy. Some claim the German tax system is the most complex one in the world.

On 27 September 2005, the Dutch Council of Economic Advisors recommended a high flat rate of 40% for income tax in the Netherlands. Some deductions would be allowed, and persons over 65 years of age would be taxed at a lower rate.

In the United States, proposals for a flat tax at the federal level have emerged repeatedly in recent decades during various political debates. Jerry Brown, former Democratic Governor of California, made the adoption of a flat tax part of his platform when running for President of the United States in 1992. At the time, rival Democratic candidate Tom Harkin ridiculed the proposal as having originated with the "Flat Earth Society". Four years later, Republican candidate Steve Forbes proposed a similar idea as part of his core platform. Although neither captured his party's nomination, their proposals prompted widespread debate about the current U.S. income tax system.

Flat tax plans that are presently being advanced in the United States also seek to redefine "sources of income"; current progressive taxes count interest, dividends and capital gains as income, for example, while Steve Forbes's variant of the flat tax would apply to wages only.

In 2005 Senator Sam Brownback, a Republican from Kansas, stated he had a plan to implement a flat tax in Washington, D.C.. This version is one flat rate of 15% on all earned income. Unearned income (in particular capital gains) would be exempt. His plan also calls for an exemption of $30,000 per family and $25,000 for singles. Mississippi Republican Senator Trent Lott stated he supports it and would add a $5,000 credit for first time home buyers and exemptions for out of town businesses. DC Delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton's position seems unclear, however DC mayor Anthony Williams has stated he is "open" to the idea.

Flat taxes have also been considered in the United Kingdom by the Conservative Party. However, it has been roundly rejected by Gordon Brown, then Chancellor of the Exchequer for Britain's ruling Labour Party, who said that it was "An idea that they say is sweeping the world, well sweeping Estonia, well a wing of the neo-conservatives in Estonia", and criticised it thus: "The millionaire to pay exactly the same tax rate as the young nurse, the home help, the worker on the minimum wage".[50]

Flat tax proposals differ in how they define and measure what is subject to tax.

Flat tax with deductions

US Congressman Dick Armey has advocated a flat tax on all income in excess of an amount shielded by household type and size. For example, draft legislation proposed by Armey would allow married couples filing jointly to deduct $26,200, unmarried heads of household to deduct $17,200, and single adults, $13,100. $5,300 would be deducted for each dependent. A household would pay tax at a flat rate of 17% on the excess. Businesses would pay a flat 17% rate on all profits. Others have put forth similar proposals with various rates and deductions. Armey defined income to include only salary, wages, and pensions; capital gains and all other sources of wealth appreciation were excluded from taxation under his proposal.[51]

While campaigning for the American presidency in 1996 and 2000, Steve Forbes called for replacing the income tax by a tax at the flat rate of 17% of consumption, defined as income minus savings, in excess of an amount determined by the type and size of the household. For example, the exempt amount for a family of four would be $42,000 per year.

Modified flat taxes have been proposed which would allow deductions for a very few items, while still eliminating the vast majority of existing deductions. Charitable deductions and home mortgage interest are the most discussed exceptions, as these are popular with voters and often used.

Hall-Rabushka flat tax

Designed by economists at the Hoover Institution, Hall-Rabushka is a fully developed flat tax on consumption (taxing consumption is thought by economists to be more efficient than taxing income).[52] Loosely speaking, Hall-Rabushka accomplishes this by taxing income and then excluding investment. An individual could file a Hall-Rabushka tax return on a postcard. Robert Hall and Alvin Rabushka have consulted extensively in designing the flat tax systems in Eastern Europe.

Negative income tax

The Negative Income Tax (NIT) which Milton Friedman proposed in his 1962 book Capitalism and Freedom is a type of flat tax. The basic idea is the same as a flat tax with personal deductions, except that when deductions exceed income, the taxable income is allowed to become negative rather than being set to zero. The flat tax rate is then applied to the resulting "negative income," resulting in a "negative income tax" the government owes the household, unlike the usual "positive" income tax, which the household owes the government.

For example, let the flat rate be 20%, and let the deductions be $20,000 per adult and $7,000 per dependent. Under such a system, a family of four making $54,000 a year would owe no tax. A family of four making $74,000 a year would owe tax amounting to 0.2(74,000-54,000) = $4,000, as under a flat tax with deductions. But families of four earning less than $54,000 per year would owe a "negative" amount of tax (that is, it would receive money from the government). E.g., if it earned $34,000 a year, it would receive a check for $4,000.

The NIT is intended to replace not just the USA's income tax, but also many benefits low income American households receive, such as food stamps and Medicaid. The NIT is designed to avoid the welfare trap—effective high marginal tax rates arising from the rules reducing benefits as market income rises. An objection to the NIT is that it is welfare without a work requirement. Those who would owe negative tax would be receiving a form of welfare without having to make a try to obtain employment. This is essentially a moral objection based on the Puritan work ethic; the advocates of negative tax agree that this would happen, but do not consider it a problem. Another objection is that the NIT subsidizes industries employing low cost labor, but this objection can also be made against current systems of benefits for the working poor.

True flat income tax

As per the definition at the beginning of the article, a true flat tax is a system of taxation where one tax rate is applied to all income with no exceptions.

In an article titled The flat-tax revolution, dated April 14, 2005, The Economist argued as follows: If the goals are to reduce corporate welfare and to enable household tax returns to fit on a postcard, then a true flat tax best achieves those goals. The flat rate would be applied to all taxable income and profits without exception or exemption. It could be argued that under such an arrangement, no one is subject to a preferential or "unfair" tax treatment. No industry receives special treatment, large households are not advantaged at the expense of small ones, etc. Moreover, the cost of tax filing for citizens and the cost of tax administration for the government would be further reduced, as under a true flat tax only businesses and the self-employed would need to interact with the tax authorities.

See also

Economic Concepts

- Fiscal drag (also known as Bracket creep)

- Taxable income elasticity (also known as Laffer Curve)

Tax Systems

- Consumption tax

- FairTax

- Income tax

- Negative income tax

- Progressive tax

- Real property use tax

- Regressive tax

- Sales tax

- Value added tax

Notes

- ↑ James, Simon (1998) A Dictionary of Taxation, Edgar Elgar Publishing Limited: Northampton, MA

- ↑ http://www.iser.essex.ac.uk/pubs/workpaps/pdf/2008-06.pdf

- ↑ http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/7304/

- ↑ http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6V85-3Y9RKX5-8&_user=10&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=2b6593e1669a80a761d9eab81765a673

- ↑ "SVG chairman breaks tax taboo", Financial Times, London, 3rd June 2007 ([1])

- ↑ Hoover Institution - Books - The Flat Tax

- ↑ Simpler taxes | The flat-tax revolution | Economist.com

- ↑ Louis Kaplow. "Accuracy, Complexity, and the Income Tax," Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization (1998), V14 N1, p.68.[2]

- ↑ The Flat Tax at Work in Russia: Year Three, Alvin Rabushka, Hoover Institution Public Policy Inquiry, www.russianeconomy.org, April 26, 2004

- ↑ The "Flat Tax(es)": Principles and Evidence

- ↑ Boortz, Neal; Linder, John (2006). The FairTax Book (Paperback ed.). Regan Books. ISBN 0-06-087549-6.

- ↑ http://www.state.gov/e/eb/ifd/2005/42068.htm

- ↑ IMF Survey: February 21, 2005

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Niedrige Steuer für alle: Osteuropa: Einige Länder haben die Einheitssteuer. Doch sie ist umstritten | ZEIT online

- ↑ The Associated Press. "Bulgarian parliament approves 2008 budget that foresees record 3 percent surplus". [3]

- ↑ Daniel Mitchell. "Albania Joins the Flat Tax Club." Cato at Liberty, April 9, 2007. [4]

- ↑ Jonilda Koci. "Albanian government approves 10% flat tax". Southeast European Times, June 4, 2007. [5]

- ↑ Alvin Rabushka. "The Flat Tax Spreads to the Czech Republic." hoover.org, 27 August 2008. [6]

- ↑ Alvin Rabushka. "Estonia Plans to Reduce its Flat-Tax Rate." March 26, 2007. [7]

- ↑ Toby Harnden. "Pioneer of the 'flat tax' taught the East to thrive." Telegraph, April 9, 2005.[8]

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 Michael Keen, Yitae Kim, and Ricardo Varsano. "The 'Flat Tax(es)': Principles and Evidence." IMF Working Paper WP/06/218.[9]

- ↑ Alvin Rabushka. "The Flat Tax Spreads to Georgia." January 3, 2005.[10]

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 Alvin Rabushka. "Flat and Flatter Taxes Continue to Spread Around the Globe." January 16, 2007.[11]

- ↑ The Economist Intelligence Unit, Kazakhstan fact sheet. "In 2007 Kazakhstan introduced several changes to the taxation system. The flat-rate VAT on all goods was reduced from 15% to 14%, and a flat rate of income tax of 10% was introduced, in place of the previous progressive range of 5-20%." [12]

- ↑ Daniel Mitchell. "If a Flat Tax is Good for Iraq, How About America?" Heritage foundation, November 10, 2003. [13].

- ↑ Alvin Rabushka. "The Flat Tax in Iraq: Much Ado About Nothing—So Far." May 6, 2004. [14]

- ↑ Noam Chomsky. "Transfer real sovereignty." znet, May 11, 2004. [15]

- ↑ http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/publication415_en.pdf

- ↑ Alvin Rabushka. "A Competitive Flat Tax Spreads to Lithuania." November 2, 2005.[16]

- ↑ "The lowest flat corporate and personal income tax rates." Invest Macedonia government web site. Retrieved June 6, 2007. [17]

- ↑ Alvin Rabushka. "The Flat Tax Spreads to Mongolia." January 30, 2007.[18]

- ↑ Alvin Rabushka. "The Flat Tax Spreads to Montenegro." April 13, 2007. [19]

- ↑ Alvin Rabushka. "Russia adopts 13% flat tax." July 26, 2000.[20]

- ↑ Alvin Rabushka. "The Flat Tax Spreads to Serbia." March 23, 2004.[21]

- ↑ Alvin Rabushka. "The Flat Tax Spreads to Ukraine." May 27, 2003.[22]

- ↑ Transnistrian government web site. [23]

- ↑ Daniel Mitchell. "Fixing a Broken Tax System with a Flat Tax." Capitalism Magazine, April 23, 2004.[24]

- ↑ Duncan B. Black. "Hyman falsely claimed Hong Kong imposes flat tax on income," Media Matters, Jan 27, 2005. [25]

- ↑ Duncan B. Black. "Fund wrong on Hong Kong 'flat tax'." Media Matters, Feb 28, 2005. [26]

- ↑ Alan Reynolds. "Hong Kong's Excellent Taxes." townhall.com, but the column was syndicated. June 6, 2005. [27]

- ↑ "Poland brings in flat tax", Adam Smith Institute

- ↑ Greece joins the flat rate tax bandwagon. By George Trefgarne, Economics Editor. The Telegraph. 2005. [28]

- ↑ "Flat tax rate on the cards." Kathimerini. 11 July 2005. [29]

- ↑ Daniel Mitchell. "Iceland Comes in From the Cold With Flat Tax Revolution." March 27, 2007.[30]

- ↑ The Globe and Mail, as quoted on Cato-at-liberty by Daniel Mitchell: "Effective this year, Iceland (population: 300,000) taxes all personal income at a flat rate of 32 per cent — which appears high because it includes municipal as well as national taxes." [31]

- ↑ Daniel Mitchell. "Iceland Joins the Flat Tax Club." Cato Tax and Budget Bulletin, February 2007. [32]

- ↑ Flat-Tax Comeback Bruce Bartlett, National Review, November 10, 2003

- ↑ Cameron is no moderate, Neil Clark, The Guardian October 24, 2005

- ↑ Albanian government to implement flat tax (SETimes.com)

- ↑ Gordon Brown's speech to the Labour party conference September 26, 2005

- ↑ The Armey Flat Tax, National Center for Policy Analysis

- ↑ Hoover Institution - Books - The Flat Tax

References

- Steve Forbes, 2005. Flat Tax Revolution. Washington: Regnery Publishing. ISBN 0-89526-040-9

- Robert Hall and Alvin Rabushka, 1995 (1985). The Flat Tax. Hoover Institution Press.

- Anthony J. Evans, "Ideas and Interests: The Flat Tax" Open Republic 1(1), 2005

External links

- The Laffer Curve: Past, Present and Future: A detailed examination of the theory behind the Laffer curve, and many case studies of tax cuts on government revenue in the United States

- Podcast of Rabushka discussing the flat tax Alvin Rabushka discusses the flat tax with Russ Roberts on EconTalk.