Iron(III) chloride

- Iron chloride redirects here. For Iron(II) chloride, see Iron(II) chloride.

| Iron(III) chloride | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| IUPAC name | Iron(III) chloride |

| Other names | ferric chloride iron trichloride molysite (mineral) Flores martis |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 7705-08-0, hexahydrate: [] |

| RTECS number | LJ9100000 |

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula | FeCl3 |

| Molar mass | 162.2 g·mol-1 hexahydrate: 270.3 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | green-black by reflected light; purple-red by transmitted light hexahydrate: yellow solid aq. solutions: brown |

| Density | 2.80 g·cm−3 40% solution: 1.4 g·ml−1 |

| Melting point |

306 °C, 579 K, 583 °F |

| Boiling point |

315 °C, 588 K, 599 °F (partial decomposition to FeCl2+Cl2) |

| Solubility in water | 92 g/100 ml (20 °C) |

| Solubility in acetone Methanol Ethanol Diethyl ether |

63 g/100 ml (18 °C) highly soluble 83 g/100 ml highly soluble |

| Viscosity | 40% solution: 12 cP |

| Structure | |

| Crystal structure | hexagonal |

| Coordination geometry |

octahedral |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Very corrosive |

| NFPA 704 |

0

3

1

|

| R-phrases | R22, R34 |

| S-phrases | S26, S28 |

| Related compounds | |

| Other anions | Iron(III) fluoride Iron(III) bromide |

| Other cations | Iron(II) chloride Manganese(II) chloride Cobalt(II) chloride Ruthenium(III) chloride |

| Related coagulants | Iron(II) sulfate Polyaluminium chloride |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa) Infobox references |

|

Iron(III) chloride, generically called ferric chloride, is an industrial scale commodity chemical compound, with the formula FeCl3. The colour of iron(III) chloride crystals depends on the viewing angle: by reflected light the crystals appear dark green, but by transmitted light they appear purple-red. Anhydrous iron(III) chloride is deliquescent, forming hydrated hydrogen chloride mists in moist air. It is rarely observed in its natural form, mineral molysite, known mainly from some fumaroles.

When dissolved in water, iron(III) chloride undergoes hydrolysis and gives off heat in an exothermic reaction. The resulting brown, acidic, and corrosive solution is used as a coagulant in sewage treatment and drinking water production, and as an etchant for copper-based metals in printed circuit boards. Anhydrous iron(III) chloride is a fairly strong Lewis acid, and it is used as a catalyst in organic synthesis.

Contents |

Chemical and physical properties

Iron(III) chloride has a relatively low melting point and boils at around 315 °C. The vapour consists of the dimer Fe2Cl6 (compare aluminium chloride) which increasingly dissociates into the monomeric FeCl3 (D3h point group molecular symmetry) at higher temperature, in competition with its reversible decomposition to give iron(II) chloride and chlorine gas.[1]

Reactions

Iron(III) chloride is a moderately strong Lewis acid, forming adducts with Lewis bases such as triphenylphosphine oxide, e.g. FeCl3(OPPh3)2 where Ph = phenyl.

Iron(III) chloride reacts with other chloride salts to give the yellow tetrahedral FeCl4− ion. Salts of FeCl4− in hydrochloric acid can be extracted into diethyl ether.

When heated with iron(III) oxide at 350 °C, iron(III) chloride gives iron oxychloride, a layered solid and intercalation host.

- FeCl3 + Fe2O3 → 3 FeOCl

In the presence of base, alkali metal alkoxides react to give the dimeric complexes:

Oxalates react rapidly with aqueous iron(III) chloride to give [Fe(C2O4)3]3−. Other carboxylate salts form complexes, e.g. citrate and tartrate.

Iron(III) chloride is a mild oxidising agent, for example capable of oxidising copper(I) chloride to copper(II) chloride. Reducing agents such as hydrazine convert iron(III) chloride to complexes of iron(II).

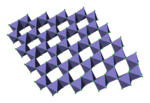

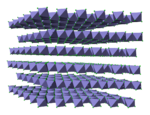

Structure

Iron(III) chloride adopts the BiI3 structure, which features octahedral Fe(III) centres interconnected by two-coordinate chloride ligands.

Preparation and production

Anhydrous iron(III) chloride may be prepared by union of the elements:[2]

Solutions of iron(III) chloride are produced industrially both from iron and from ore, in a closed-loop process.

- Dissolving pure iron in a solution of iron(III) chloride

Fe(s) + 2 FeCl3(aq) → 3 FeCl2(aq) - Dissolving iron ore in hydrochloric acid

Fe3O4(s) + 8 HCl(aq) → FeCl2(aq) + 2 FeCl3(aq) + 4 H2O - Upgrading the iron(II) chloride with chlorine

2 FeCl2(aq) + Cl2(g) → 2 FeCl3(aq)

Alternatively, iron(II) chloride can be oxidised with sulfur dioxide:

- 32 FeCl2 + 8 SO2 + 32 HCl → 32 FeCl3 + S8 + 16 H2O

Like many other hydrated metal chlorides, hydrated iron(III) chloride can be converted to the anhydrous salt by refluxing with thionyl chloride.[3] The hydrate cannot be converted to anhydrous iron(III) chloride by only heat, as instead HCl is evolved and iron oxychloride forms.

Uses

Industrial

In industrial application, iron(III) chloride is used in sewage treatment and drinking water production.[4] In this application, FeCl3 in slightly basic water reacts with the hydroxide ion to form a floc of iron(III) hydroxide, or more precisely formulated as FeO(OH)-, that can remove suspended materials.

- Fe3+ + 4 OH− → Fe(OH)4− → FeO(OH)2−·H2O

It is also used as a leaching agent in chloride hydrometallurgy, [5] for example in the production of Si from FeSi. (Silgrain process)[6]

Another important application of iron(III) chloride is etching copper in two-step redox reaction to copper(I) chloride and then to copper(II) chloride in the production of printed circuit boards.[7]

- FeCl3 + Cu → FeCl2 + CuCl

- FeCl3 + CuCl → FeCl2 + CuCl2

Iron(III) chloride is used as catalyst for the reaction of ethylene with chlorine, forming ethylene dichloride (1,2-dichloroethane), an important commodity chemical, which is mainly used for the industrial production of vinyl chloride, the monomer for making PVC.

- H2C=CH2 + Cl2 → ClCH2CH2Cl

Laboratory use

In the laboratory iron(III) chloride is commonly employed as a Lewis acid for catalysing reactions such as chlorination of aromatic compounds and Friedel-Crafts reaction of aromatics. It is less powerful than aluminium chloride, but in some cases this mildness leads to higher yields, for example in the alkylation of benzene:

The ferric chloride test is a traditional colorimetric test for phenols, which uses a 1% iron(III) chloride solution that has been neutralised with sodium hydroxide until a slight precipitate of FeO(OH) is formed.[8] The mixture is filtered before use. The organic substance is dissolved in water, methanol or ethanol, then the neutralised iron(III) chloride solution is added—a transient or permanent coloration (usually purple, green or blue) indicates the presence of a phenol or enol.

Other uses

- Anhydrous iron(III) chloride is sometimes used as a drying reagent in certain reactions.

- Iron(III) chloride is sometimes used by American coin collectors to identify the dates of Buffalo nickels that are so badly worn that the date is no longer visible.

- Iron(III) chloride is commonly used by knife craftsmen and sword smiths to stain blades, as to give a contrasting effect to the metal, and to view metal layering or imperfections.

- Iron(III) chloride is often used to etch the widmanstatten pattern in Iron Meteorites .

- Iron(III) chloride is necessary for the etching of photogravure plates for printing photographic and fine art images in intaglio and for etching rotogravure cylinders used in the printing industry.

- Iron(III) chloride is used in veterinary practice to treat overcropping of an animal's claws, particularly when the overcropping results in bleeding.

- Iron(III) chloride reacts with cyclopentadienylmagnesium bromide in one preparation of ferrocene, a metal-sandwich complex.[9]

- Iron(III) chloride is sometimes used in the technique of Raku Firing as an additive during the reduction process, turning a pottery piece a burnt orange color due to the iron content present in the reducing atmosphere.

Safety

Iron(III) chloride is toxic, highly corrosive and acidic. The anhydrous material is a powerful dehydrating agent.

See also

- iron(II) sulfate

- aluminium chloride

References

- ↑ Holleman, A.F.; Wiberg, E. (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- ↑ Tarr, B.R. (1950). "Anhydrous Iron(III) Chloride". Inorganic Syntheses 3: 191–194. doi:.

- ↑ Pray, Alfred R.; Richard F. Heitmiller, Stanley Strycker (1990). "Anhydrous Metal Chlorides". Inorganic Syntheses 28: 321–323. doi:.

- ↑ Water Treatment Chemicals. Akzo Nobel Base Chemicals. 2007. http://www.basechemicals.com/NR/rdonlyres/ACEEFEE2-EB7D-4A36-B52F-E7B27BFBF87E/20148/AkzoWTCBrochureENG.pdf. Retrieved on 2007-10-26.

- ↑ Separation and Purification Technology 51 (2006) pp 332-337

- ↑ Chem. Eng. Sci. 61 (2006) pp 229-245

- ↑ Greenwood, N.N.; A. Earnshaw (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed. ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- ↑ Furnell, B.S.; et al. (1989). Vogel's Textbook of Practical Organic Chemistry (5th edition ed.). New York: Longman/Wiley.

- ↑ Kealy, T.J. (1951). "A New Type of Organo-Iron Compound". Nature 168: 1040. doi:.

Further reading

- Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 71st edition, CRC Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1990.

- The Merck Index, 7th edition, Merck & Co, Rahway, New Jersey, USA, 1960.

- D. Nicholls, Complexes and First-Row Transition Elements, Macmillan Press, London, 1973.

- A.F. Wells, 'Structural Inorganic Chemistry, 5th ed., Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 1984.

- J. March, Advanced Organic Chemistry, 4th ed., p. 723, Wiley, New York, 1992.

- Handbook of Reagents for Organic Synthesis: Acidic and Basic Reagents, (H. J. Reich, J. H. Rigby, eds.), Wiley, New York, 1999.