Cat

| Cat[1] | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||

| Conservation status | ||||||||||||||

|

Domesticated

|

||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||

| Felis catus (Linnaeus, 1758)[2] |

||||||||||||||

| Synonyms | ||||||||||||||

|

Felis catus domestica (invalid junior synonym)[3] |

The cat (Felis catus), also known as the domestic cat or house cat to distinguish it from other felines, is a small predatory carnivorous species of crepuscular mammal that is valued by humans for its companionship and its ability to hunt vermin, snakes and scorpions. It has been associated with humans for at least 9,500 years.[5]

A skilled predator, the cat is known to hunt over 1,000 species for food. It can be trained to obey simple commands. Individual cats have also been known to learn on their own to manipulate simple mechanisms, such as doorknobs. Cats use a variety of vocalizations and types of body language for communication, including meowing, purring, hissing, growling, squeaking, chirping, clicking, and grunting.[6] Cats may be the most popular pet in the world, with over 600 million in homes all over the world.[7] They are also bred and shown as registered pedigree pets. This hobby is known as the "cat fancy".

Until recently the cat was commonly believed to have been domesticated in ancient Egypt, where it was a cult animal.[8] However a 2007 study found that the lines of descent of all house cats probably run through as few as five self-domesticating African Wildcats (Felis silvestris lybica) circa 8000 BC, in the Near East.[4]

Contents |

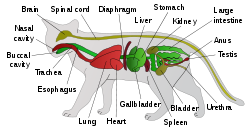

Physiology

Size

Cats typically weigh between 2.5 and 7 kg (5.5–16 pounds); however, some breeds, such as the Maine Coon, can exceed 11.3 kilograms (24.9 lb). Some have been known to reach up to 23 kilograms (51 lb) due to overfeeding. Conversely, very small cats (less than 1.8 kilograms (4.0 lb)) have been reported.[9]

The largest cat ever was officially reported to have weighed in at about 21.297 kilograms (46.952 lb) (46 lb 15.25 oz).[10][11] The smallest cat ever officially recorded weighed around 3lbs (1.36 kg). [12]

Skeleton

Cats have 7 cervical vertebrae like almost all mammals, 13 thoracic vertebrae (humans have 12), 7 lumbar vertebrae (humans have 5), 3 sacral vertebrae like most mammals (humans have 5 because of their bipedal posture), and, except for Manx cats, 22 or 23 caudal vertebrae (humans have 3 to 5, fused into an internal coccyx). The extra lumbar and thoracic vertebrae account for the cat's enhanced spinal mobility and flexibility, compared with humans. The caudal vertebrae form the tail, used by the cat as a counterbalance to the body during quick movements. Cats also have free-floating clavicle bones, which allows them to pass their body through any space into which they can fit their heads.[13]

Mouth

Cats have highly specialized teeth for the killing of prey and the tearing of meat. The premolar and first molar together compose the carnassial pair on each side of the mouth, which efficiently functions to shear meat like a pair of scissors. While this is present in canids, it is highly developed in felines. The cat's tongue has sharp spines, or papillae, useful for retaining and ripping flesh from a carcass. These papillae are small backward-facing hooks that contain keratin which also assist in their grooming.

As facilitated by their oral structure, cats use a variety of vocalizations and types of body language for communication, including meowing, purring, hissing, growling, squeaking, chirping, clicking, and grunting.[6]

Ears

Thirty-two individual muscles in each ear allow for a manner of directional hearing:[14] a cat can move each ear independently of the other. Because of this mobility, a cat can move its body in one direction and point its ears in another direction. Most cats have straight ears pointing upward. Unlike dogs, flap-eared breeds are extremely rare. (Scottish Folds are one such exceptional mutation.) When angry or frightened, a cat will lay back its ears, to accompany the growling or hissing sounds it makes. Cats also turn their ears back when they are playing, or to listen to a sound coming from behind them. The angle of cats' ears is an important clue to their mood.

Legs

Cats, like dogs, are digitigrades. They walk directly on their toes, with the bones of their feet making up the lower part of the visible leg. Cats are capable of walking very precisely, because like all felines they directly register; that is, they place each hind paw (almost) directly in the print of the corresponding forepaw, minimizing noise and visible tracks. This also provides sure footing for their hind paws when they navigate rough terrain.

Like nearly all members of family Felidae, cats have retractable claws. In their normal, relaxed position the claws are sheathed with the skin and fur around the toe pads. This keeps the claws sharp by preventing wear from contact with the ground and allows the silent stalking of prey. The claws on the forefeet are typically sharper than those on the hind feet.[15] Cats can voluntarily extend their claws on one or more paws. They may extend their claws in hunting or self-defense, climbing, "kneading", or for extra traction on soft surfaces (bedspreads, thick rugs, etc.). It is also possible to make a cooperative cat extend its claws by carefully pressing both the top and bottom of the paw. The curved claws may become entangled in carpet or thick fabric, which may cause injury if the cat is unable to free itself.

Most cats have five claws on their front paws, and four or five on their rear paws. Because of an ancient mutation, however, domestic cats are prone to polydactylyism, and may have six or seven toes. The fifth front claw (the dewclaw) is proximal to the other claws. More proximally, there is a protrusion which appears to be a sixth "finger". This special feature of the front paws, on the inside of the wrists, is the carpal pad, also found on the paws of big cats and dogs. It has no function in normal walking, but is thought to be an anti-skidding device used while jumping.

Skin

Cats possess rather loose skin; this allows them to turn and confront a predator or another cat in a fight, even when it has a grip on them. This is also an advantage for veterinary purposes, as it simplifies injections.[16] In fact, the lives of cats with kidney failure can sometimes be extended for years by the regular injection of large volumes of fluid subcutaneously, which serves as an alternative to dialysis.[17][18]

The particularly loose skin at the back of the neck is known as the scruff, and is the area by which a mother cat grips her kittens to carry them. As a result, cats tend to become quiet and passive when gripped there. This behavior also extends into adulthood, when a male will grab the female by the scruff to immobilize her while he mounts, and to prevent her from running away as the mating process takes place. [19]

This technique can be useful when attempting to treat or move an uncooperative cat. However, since an adult cat is heavier than a kitten, a pet cat should never be carried by the scruff, but should instead have its weight supported at the rump and hind legs, and at the chest and front paws. Often (much like a small child) a cat will lie with its head and front paws over a person's shoulder, and its back legs and rump supported under the person's arm.

Senses

Cat senses are attuned for hunting. Cats have highly advanced hearing, eyesight, taste, and touch receptors, making the cat extremely sensitive among mammals.

Cats' night vision is superior to humans although their vision in daylight is inferior. Cat eyes have a tapetum lucidum and cat eyes that are blue typically lack melanin and hence can show the red-eye effect (see odd-eyed cat).

Humans and cats have a similar range of hearing on the low end of the scale, but cats can hear much higher-pitched sounds, up to 64 kHz, which is 1.6 octaves above the range of a human, and even one octave above the range of a dog.[20]

A domestic cat's sense of smell is about fourteen times as strong as a human's.[21]

Due to a mutation in an early cat ancestor, one of two genes necessary to taste sweetness may have been lost by the cat family.[22]

To aid with navigation and sensation, cats have dozens of movable vibrissae (whiskers) over their body, especially their face.

Metabolism

Cats conserve energy by sleeping more than most animals, especially as they grow older. The daily duration of sleep varies, usually 12–16 hours, with 13–14 being the average. Some cats can sleep as much as 20 hours in a 24-hour period. The term cat nap refers to the cat's ability to fall asleep (lightly) for a brief period and has entered the English lexicon – someone who nods off for a few minutes is said to be "taking a cat nap".

Due to their crepuscular nature, cats are often known to enter a period of increased activity and playfulness during the evening and early morning, dubbed the "evening crazies", "night crazies", "elevenses" or "mad half-hour" by some.[23][24]

The temperament of a cat can vary depending on the breed and socialization. Cats with oriental body types tend to be thinner and more active, while cats that have a cobby body type tend to be heavier and less active.

The normal body temperature of a cat is between 38 and 39 °C (101 and 102.2 °F).[25] A cat is considered febrile (hyperthermic) if it has a temperature of 39.5 °C (103 °F) or greater, or hypothermic if less than 37.5 °C (100 °F). For comparison, humans have a normal temperature of approximately 36.8 °C (98.6 °F). A domestic cat's normal heart rate ranges from 140 to 220 beats per minute, and is largely dependent on how excited the cat is. For a cat at rest, the average heart rate should be between 150 and 180 bpm, about twice that of a human (average 80 bpm).

Genetics

- See also: Cat coat genetics

A 2007 study published in the journal Science asserts that all house cats are descended from a group of self-domesticating desert wildcats Felis silvestris lybica circa 10,000 years ago, in the Near East.[4]

The domesticated cat and its closest wild ancestor are both diploid organisms that possess 38 chromosomes,[26] in which over 200 heritable genetic defects have been identified, many homologous to human inborn errors. Specific metabolic defects have been identified underlying many of these feline diseases. There are several genes responsible for the hair color identified. The combination of them gives different phenotypes.

Features like hair length, lack of tail or presence of a very short tail (bobtail cat) are also determined by single alleles and modified by polygenes.

The Cat Genome Project, sponsored by the Laboratory of Genomic Diversity at the U.S. National Cancer Institute Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center in Frederick, Maryland, focuses on the development of the cat as an animal model for human hereditary disease, infectious disease, genome evolution, comparative research initiatives within the family Felidae, and forensic potential.

All felines, including the big cats, have a genetic anomaly that may prevent them from tasting sweetness,[22] which is a likely factor for their indifference to or avoidance of fruits, berries, and other sugary foods.

Feeding and diet

- Further information: Cat food

Cats are classified as obligate carnivores, because their physiology is geared toward efficient processing of meat, and lacks efficient processes for digesting plant matter. The cat cannot produce its own taurine (an essential organic acid) in its own body and as it is contained in flesh, the cat must eat flesh to survive (see Taurine and cats). Similarly as with its teeth, a cat's digestive tract has become specialized over time to suit meat eating, having shortened in length only to those segments of intestine best able to break down proteins and fats from animal flesh.[27] This trait severely limits the cat's ability to properly digest, metabolize, and absorb plant-derived nutrients, as well as certain fatty acids. For example, taurine is scarce in plants but abundant in meats. It is a key amino sulfonic acid for eye health in cats. Taurine deficiency can cause a condition called macular degeneration wherein the cat's retina slowly degenerates, eventually causing irreversible blindness.

Despite the cat's meat-oriented physiology, it is still quite common for a cat to supplement its carnivorous diet with small amounts of grass, leaves, shrubs, houseplants, or other plant matter. One theory suggests this behavior helps cats regurgitate if their digestion is upset; another is that it introduces fiber or trace minerals into the diet. In this context, caution is recommended for cat owners because some houseplants are harmful to cats. For example, the leaves of the Easter Lily can cause permanent and life-threatening kidney damage to cats, and Philodendron are also poisonous to cats. The Cat Fanciers' Association has a full list of plants harmful to cats.[28]

There are several vegetarian or vegan commercially available cat foods supplemented with chemically synthesized taurine and other added nutrients that attempt to address nutritional shortfalls.

Cats can be selective eaters (which may be due in some way to the aforementioned mutation which caused their species to lose sugar-tasting ability). Unlike most mammals, cats can voluntarily starve themselves indefinitely despite being presented with palatable food, even a food which they had previously readily consumed.

Cats have a fondness for catnip, which is sensed by their olfactory systems. Many enjoy consuming catnip, and most will often roll in it, paw at it, and occasionally chew on it.

Toxic sensitivity

The liver of a cat is less effective at detoxification than those of other animals, including humans and dogs; therefore exposure to many common substances considered safe for households may be dangerous to them.[29][30] In general, the cat's environment should be examined for the presence of such toxins and the problem corrected or alleviated as much as possible; in addition, where sudden or prolonged serious illness without obvious cause is observed, the possibility of toxicity must be considered, and the veterinarian informed of any such substances to which the cat may have had access.

For instance, the common painkiller paracetamol or acetaminophen, sold under brand names such as Tylenol and Panadol, is extremely toxic to cats; because they naturally lack enzymes needed to digest it, even minute portions of doses safe for humans can be fatal[31][30] and any suspected ingestion warrants immediate veterinary attention.[32] Even aspirin, which is sometimes used to treat arthritis in cats, is much more toxic to them than to humans and must be administered cautiously.[30] Similarly, application of minoxidil (Rogaine) to the skin of cats, either accidental or by well-meaning owners attempting to counter loss of fur, has sometimes proved fatal.[33][34]

In addition to such obvious dangers as insecticides and weed killers, other common household substances that should be used with caution in areas where cats may be exposed to them include mothballs and other naphthalene products,[30] as well as phenol based products often used for cleaning and disinfecting near cats' feeding areas or litter boxes, such as Pine-Sol, Dettol (Lysol), hexachlorophene, etc.[30] which, although they are widely used without problem, have been sometimes seen to be fatal.[35] Ethylene glycol, often used as an automotive antifreeze, is particularly appealing to cats, and as little as a teaspoonful can be fatal.[36]

Many human foods are somewhat toxic to cats; theobromine in chocolate can cause theobromine poisoning, for instance, although few cats will eat chocolate. Toxicity in cats ingesting relatively large amounts of onions or garlic has also been reported.[30] Even such seemingly safe items as cat food packaged in pull tab tin cans have been statistically linked to hyperthyroidism; although the connection is far from proven, suspicion has fallen on the use of bisphenol A-based plastics, another phenol based product as discussed above, to seal such cans.[30]

Many houseplants are at least somewhat toxic to many species, cats included[29] and the consumption of such plants by cats is to be avoided.

Behavior

- See also: Cat behavior and cat communication

Sociability

For cats, life in close proximity with humans (and other animals kept by humans) amounts to a "symbiotic social adaptation" which has developed over thousands of years. It has been suggested that, ethologically, the human keeper of a cat functions as a sort of surrogate for the cat's mother, and that adult domestic cats live their lives in a kind of extended kittenhood,[37] a form of behavioral neoteny.

Cats may express affection towards their human companions, especially if they imprint on them at a very young age and are treated with consistent affection.

Regardless of the average sociability of any given cat or of cats in general, there are still any number of cats who meet or exceed the negative feline stereotype insofar as being poorly socialized. Older cats have also been reported to sometimes develop aggressiveness towards kittens, which may include biting and scratching; this type of behavior is known as Feline Asocial Aggression.[38]

Cohabitation

One may see natural house cat behavior by observing feral domestic cats, which are social enough to form colonies.[39] Each cat in a colony holds a distinct territory, with sexually active males having the largest territories, and neutered cats having the smallest. Between these territories are neutral areas where cats watch and greet one another without territorial conflicts. Outside these neutral areas, territory holders usually aggressively chase away stranger cats, at first by staring, hissing, and growling, and if that does not work, by short but noisy and violent attacks.

Despite cohabitation in colonies, cats do not have a social survival strategy, or a pack mentality. This mainly means that an individual cat takes care of all basic needs on its own (e.g., finding food, and defending itself), and thus cats are always lone hunters; they do not hunt in groups as dogs or lions do.

Cats frequently tonguebathe themselves (see Hygiene). The chemistry of their saliva, expended during their frequent grooming, appears to be a natural deodorant. Thus, a cat's cleanliness would aid in decreasing the chance a prey animal could notice the cat's presence. By contrast, dog odor is an advantage in hunting, for a dog is a pack hunter; part of the pack stations itself upwind, and its odor drives prey towards the rest of the pack stationed downwind. This requires a cooperative effort, which in turn requires communication skills. No such communication skills are required of a lone hunter.

Fighting

When engaged in feline-to-feline combat for self-defense, territory, reproduction, or dominance, fighting cats make themselves appear more impressive and threatening by raising their fur and arching their backs, thus increasing their apparent size. Cats also behave this way while playing. Attacks usually comprise powerful slaps to the face and body with the forepaws as well as bites, but serious damage is rare; usually the loser runs away with little more than a few scratches to the face, and perhaps the ears. Cats will also throw themselves to the ground in a defensive posture to rake with their powerful hind legs. Normally, serious negative effects will be limited to possible infections of the scratches and bites; though these have been known to sometimes kill cats if untreated. In addition, such fighting is believed to be the primary route of transmission of feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV). Sexually active males will usually be in many fights during their lives, and often have decidedly battered faces with obvious scars and cuts to the ears and nose. Not only males will fight; females will also fight over territory or to defend their kittens.

Play

Domestic cats, especially young kittens, are known for their love of play. This behavior mimics hunting and is important in helping kittens learn to stalk, capture and kill prey.[40] Many cats cannot resist a dangling piece of string, or a piece of rope drawn randomly and enticingly across the floor. This well known love of string is often depicted in cartoons and photographs, which show kittens or cats playing with balls of yarn. It is probably related to hunting instincts, including the common practice of kittens hunting their mother's and each other's tails. If string is ingested, however, it can become caught in the cat’s stomach or intestines, causing illness, or in extreme cases, death. Due to possible complications caused by ingesting a string, string play is sometimes replaced with a laser pointer's dot, which some cats will chase. While caution is called for, there are no documented cases of feline eye damage from a laser pointer, and the combination of precision needed and low energy involved make it a remote risk. A common compromise is to use the laser pointer to draw the cat to a prepositioned toy so the cat gets a reward at the end of the chase. A regular flashlight with a well-focused light spot has been commonly used in such play for decades, preceding the availability of consumer laser pointers.

Cats will also engage in play fighting, with each other and with human partners. Humans "wrestling" with a supine cat, however, should be wary: if the cat is overstimulated or startled it may decide that the play has turned serious and cease to pull its punches; this can lead to serious scratches and occasionally even bites.

Hunting

Much like their big cat relatives, domestic and feral cats are very effective predators.[41] Domestic felines ambush or pounce upon and immobilize vertebrate prey using tactics similar to those of leopards and tigers. Having overpowered such prey, a cat delivers a lethal neck bite with its long canine teeth that either severs the prey's spinal cord with irreversible paralysis to prey, causes fatal bleeding by puncturing the carotid artery or the jugular vein, or asphyxiates the prey by crushing its trachea.

One poorly understood element of cat hunting behavior is the presentation of prey to human owners. Ethologist Paul Leyhausen proposed that cats adopt humans into their social group, and share excess kill with others in the group according to the local pecking order, in which humans are placed at or near the top.[42] However, anthropologist and animal scientist Desmond Morris in his 1986 book Catwatching suggests that when cats bring home mice or birds they have caught, they are teaching their human to hunt, or helping their human as if feeding (his words) "an elderly, inept kitten". Another possibility is that presenting the kill might be a relic of a kitten's behavior of demonstrating for its mother's approval that it has developed the necessary skill for hunting. Indoor cats will often retain their hunting instinct and deliver small household items to their owners, such as watches, pens, pencils, and other objects they can carry in their mouths.

Reproduction

Cats are seasonally polyestrous, which means they may have many periods of heat over the course of a year. A heat period lasts about 4 to 7 days if the female is bred; if she is not, the heat period lasts longer.

Multiple males will be attracted to a female in heat. The males will fight over her, and the victor wins the right to mate. At first, the female will reject the male, but eventually the female will allow the male to mate. The female will give a loud yowl as the male pulls out of her. After mating, the female will give herself a thorough wash. If a male attempts to breed with her at this point, the female will attack him. Once the female is done grooming, the cycle will repeat.

The male cat's penis has spines which point backwards. Upon withdrawal of the penis, the spines rake the walls of the female's vagina, which may cause ovulation. Because this does not always occur, females are rarely impregnated by the first male with which they mate. Furthermore, cats are superfecund; that is, a female may mate with more than one male when she is in heat, meaning different kittens in a litter may have different fathers.

The gestation period for cats is approximately 63–65 days. The size of a litter averages three to five kittens, with the first litter usually smaller than subsequent litters. Kittens are weaned at between six and seven weeks, and cats normally reach sexual maturity at 4–10 months (females) and to 5–7 months (males).

Cats are ready to go to new homes at about 12 weeks old (the recommended minimum age by Fédération Internationale Féline), or when they are ready to leave their mother. Cats can be surgically sterilized (spayed or castrated) as early as 6–8 weeks to limit unwanted reproduction. This surgery also prevents undesirable sex-related behavior, such as territory marking (spraying urine) in males and yowling (calling) in females. If a cat is neutered after such behavior has been learned, however, then the behavior may persist.

Hygiene

Cats are known for their fastidious cleanliness. They groom themselves by licking their fur, employing their hooked papillae and saliva. As mentioned, their saliva is a powerful cleaning agent and deodorant. Many cats also enjoy grooming humans or other cats. Sometimes the act of grooming another cat is initiated as an assertion of superior position in the pecking order of a group (dominance grooming).

Some cats occasionally regurgitate hairballs of fur that have collected in their stomachs as a result of their grooming. Longhaired cats are more prone to this than shorthaired cats. Hairballs can be prevented with certain cat foods and remedies that ease elimination of the hair and regular grooming of the coat with a comb or stiff brush.

Scratching

Cats are naturally driven to periodically hook their front claws into suitable surfaces and pull backwards, in order to clean the claws and remove the worn outer sheath, as well as exercise and stretch their muscles. This scratching behavior seems enjoyable to the cat, and even declawed cats will go through elaborate scratching routines with every evidence of great satisfaction, despite the total lack of results. Some researchers believe this is due to scent glands located in their pads, and that scratching is effectively a part of marking territory.

Fondness for heights

Most breeds of cat have a noted fondness for settling in high places, or perching. Animal behaviorists have posited a number of explanations, the most common being that height gives the cat a better observation point, allowing it to survey its territory and become aware of activities of people and other pets in the area. In the wild, a higher place may serve as a concealed site from which to hunt; domestic cats are known to strike prey by pouncing from such a perch as a tree branch, as does a leopard.[43] Height, therefore, can also give cats a sense of security and prestige.

During a fall from a high place, a cat can reflexively twist its body and right itself using its acute sense of balance and flexibility.[44] This is known as the cat's "righting reflex". It always rights itself in the same way, provided it has the time to do so, during a fall. The height required for this to occur in most cats (safely) is around 90 cm (3 feet). Cats without a tail also have this ability, since a cat mostly moves its hind legs and relies on conservation of angular momentum to set up for landing, and the tail is in fact little used for this feat.[45]

However, cats' fondness for high spaces can dangerously test the righting reflex. The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals warns owners to safeguard the more dangerous perches in their homes, to avoid "high-rise syndrome", where an overconfident cat falls from an extreme height.[46]

Ecology

Habitat

The African Wildcat (Felis silvestris lybica), ancestor of the domestic cat, is believed to have evolved in a desert climate, as evident in the behavior common to both the domestic and wild forms. Wildcats (Felis sylvestris) are native to all continents other than Australia and Antarctica, although feral cats have become apex predators in the Australian Outback where they are menaces to wildlife.[47] Their feces are usually dry, and cats prefer to bury them in sandy places. Urine is highly concentrated, which allows the cat to retain as much fluid as possible. They are able to remain motionless for long periods, especially when observing prey and preparing to pounce. In North Africa there are still small wildcats that are probably related closely to the ancestors of today's domesticated cat breeds.

Being closely related to desert animals, cats enjoy heat and solar exposure, often sleeping in a sunny area during the heat of the day, as part of a general preference for warm temperatures. Where humans typically start to feel uncomfortable when their skin temperature gets higher than about 44.5 °C (112 °F), by contrast cats do not start to show signs of discomfort until their skin reaches about 52 °C (126 °F).

Overall, cats can easily withstand the heat and cold of a temperate climate, so long as the cold is not for extended periods. Although certain breeds such as the Norwegian Forest Cat and Maine Coon have developed heavier coats of fur than other cats, they have little resistance against moist cold (e.g., fog, rain and snow) and struggle to maintain their 39 °C (102 °F) body temperature when wet. In direct relation to that fact, most cats dislike immersion in water. One major exception is the Turkish Van breed which has an unusual fondness for water.[48] Abyssinians and Bengals are also reported to be more tolerant of water than most cats.

Impact of hunting

The domestic cat hunts and eats over a thousand species, many of them invertebrates, especially insects — many big cats will eat fewer than a hundred different species. Although theoretically big cats can kill most of these species as well, they often do not due to the relatively low nutritional content that smaller animals provide for the effort. An exception is the leopard, which commonly hunts rabbits and many other smaller animals. Even well-fed domestic cats may hunt and kill birds, mice, rats, scorpions, cockroaches, grasshoppers, and other small animals in their environment.

As a consequence of their exceptional hunting ability, cats can be quite destructive to ecosystems in which they are not native, where local species have not had time to adapt to feline introduction. In some cases, cats have contributed to or caused extinctions — for example, see the case of the Stephens Island Wren. Due to their hunting behavior, in many countries feral cats are considered pests. Domestic cats are occasionally also required to have contained cat runs or to be kept inside entirely, as they can be hazardous to locally endangered bird species. For instance, various municipalities in Australia have enacted such legislation. In some localities, owners fit their cat with a bell in order to warn prey of its approach (although some cats may figure out how and when the bell works, thereby learning more careful movements to avoid the ringing).

House cats

Domestication

In 2004, a grave was excavated in Cyprus that contained the skeletons, laid close to one another, of both a human and a cat. The grave is estimated to be 9,500 years old, pushing back the earliest known feline-human association significantly.[5][49][50]

In captivity, indoor cats typically live 14 to 20 years, though the oldest-known cat lived to age 36.[51] Domesticated cats tend to live longer if they are not permitted to go outdoors (reducing the risk of injury from fights or accidents and exposure to diseases) and if they are neutered. Some such benefits are: castrated male cats cannot develop testicular cancer, spayed female cats cannot develop ovarian cancer, and both have a reduced risk of mammary cancer.[52]

Like some other domesticated animals, cats live in a mutualistic arrangement with humans. It is believed that the benefit of removing rats and mice from humans' food stores outweighed the trouble of extending the protection of a human settlement to a formerly wild animal, almost certainly for humans who had adopted a farming economy. Unlike the dog, which also hunts and kills rodents, the cat does not eat grains, fruits, or vegetables.

In modern rural areas, farms often have dozens of semi-feral cats. Hunting in the barns and the fields, they kill and eat rodents that would otherwise spoil large parts of the grain crop. Many pet cats successfully hunt and kill rabbits, rodents, birds, lizards, frogs, fish, and large insects by instinct, but might not eat their prey.

In modern urban areas, some people find feral and free-roaming pet cats annoying and intrusive. Unaltered cats can engage in persistent nighttime calling (termed caterwauling) and defecation or "marking" of private property. Indoor confinement of pets and TNR programs for feral cats can help; some people also use cat deterrents to discourage cats from entering their property.

Interaction with humans

Human attitudes toward cats vary widely. Some people keep cats for casual companionship as pets. Others go to great lengths to pamper their cats, sometimes treating them as if they were children. Cats are also bred and shown as registered pedigree pets, in a hobby known as the cat fancy.

Because of their small size, domesticated house cats pose almost no danger to adult humans — the main hazard is the possibility of infection (e.g., cat scratch disease, or, rarely, rabies) from a cat bite or scratch. Cats can also potentially inflict severe scratches or puncture an eye, though this is quite rare (although dogs have been known to be blinded by cats in fights, where the cat specifically and accurately targeted the eyes of the larger animal).

Allergens

Allergic reactions to cat dander and/or cat saliva inspire one of the most common reasons people cite for disliking cats. Some humans who are allergic to cats—typically manifested by hay fever, asthma or a skin rash—quickly acclimate themselves to a particular animal and live comfortably in the same house with it, while retaining an allergy to cats in general.[53] However, this should not be depended upon.

Many humans find the rewards of cat companionship outweigh the discomfort and problems associated with these allergens. Some cope with the problem by taking prescription allergy medicine, along with bathing their cats frequently (weekly bathing will eliminate about 90% of the cat dander present in the environment). There are also attempts to breed cats that are less likely to provoke an allergic reaction.

Trainability

Some owners seek to train their cat in performing tricks commonly exhibited by dogs, such as jumping, though this is rare. Individual cats have been known to learn to manipulate simple mechanisms, like sink faucets, by themselves or after prompting/encouraging. With effort and patience on the part of an owner, the average cat can usually be trained to at least obey simple commands such as "get off the furniture" or "come to dinner". In general though, the seeming intractability of the ordinary house cat to training has long inspired the simile 'like herding cats', as a general expression to describe any situation with a stubborn or uncooperative learner.

Indoor scratching

Cats are naturally driven to periodically hook their front claws into suitable surfaces and pull backwards, in order to clean the claws. Indoor cats benefit from being provided with a scratching post so that they are less likely to use carpet or furniture which they can easily ruin.[54] Commercial scratching posts typically are covered in carpeting or upholstery, but some authorities advise against this practice, as not making it clear to the cat which surfaces are permissible and which are not; they suggest using a plain wooden surface, or reversing the carpeting on the posts so that the rougher texture of the carpet backing is a more attractive alternative to the cat than the floor covering. Scratching posts made of sisal rope or corrugated cardboard are also commonly found. Some indoor cats, however, especially those that were taken as kittens from feral colonies, may not understand the concept of a scratching post, and as a result will ignore it.

Although scratching can serve cats to keep their claws from growing excessively long, their nails can be trimmed if necessary with a small nail trimmer designed for humans, or a small pair of electrician's diagonal cutting pliers, or a guillotine type cutter specifically designed for animal nail trimming. Care must always be taken to avoid cutting the quick of the claw, analogous to cutting into the tip of a finger and equally painful and bloody. The position of the quick can be easily seen through the translucent nail of a cat with light colored claws but not in cats with dark colored nails, who therefore require carefully trimming of only small amounts from the nails.

Scratching can be reduced and even eliminated by disciplining the cat with a quick spritz from a water bottle when the cat is scratching or by applying a product called Sticky Paws (similar to double-sided tape) to the surface the cat is prone to scratch. Cats are also repelled by citrus scents, and a citrus-scented product may also help stop unwanted furniture destruction. Pet supply stores also sell bitter apple spray, which cats do not like and will generally avoid.

Declawing

Declawing is a surgical procedure, known as onychectomy, to remove the claw and first bone of each digit of a cat's paws. Declawing is most commonly only performed on front feet.

Declawing may be performed to prevent the cat from damaging furniture. Additionally, declawing may be performed on vicious cats, cats that frequently fight with other pets, or cats that are too efficient at predation of animals. In the United States, landlords sometimes require that tenants' cats be declawed.

Declawing is controversial and is uncommon outside of North America. It is sometimes prohibited by animal cruelty laws.

Waste

Indoor cats are usually provided with a litter box containing litter, typically bentonite, but sometimes other absorbent material such as shredded paper or wood chips, or sometimes sand or similar material. This arrangement serves the same purpose as a toilet for humans. It should be cleaned daily and changed often, depending on the number of cats in a household and the type of litter; if it is not kept clean, a cat may be fastidious enough to find other locations in the house for urination or defecation. This may also happen for other reasons; for instance, if a cat becomes constipated and defecation is uncomfortable, it may associate the discomfort with the litter box and avoid it in favor of another location. A litterbox is recommended for indoor-outdoor cats as well.

Daily attention to the litter box also serves as a monitor of the cat's health. Numerous variations on litter and litter box design exist, including some which automatically sift the litter after each use. Bentonite or clumping litter is a variation which absorbs urine into clumps which can be sifted out along with feces, and thus stays cleaner longer with regular sifting, but has sometimes been reported to cause health problems in some cats.[55] Those with toxoplasmosis-infected cats living in habitat areas of sea otters[56] may wish to dispose of droppings in the trash, rather than flushing them down the toilet. [57]

Litterboxes may pose a risk of toxoplasmosis transmission to susceptible pregnant women and immuno-compromised individuals. Most indoor-only cats are not normally exposed to the disease and are not carriers. Transmission risk may be reduced by daily litterbox cleaning by someone other than the susceptible individual.

Some cats can be trained to use the human toilet, eliminating the litter box and its attendant expense, unpleasant odor, and the need to use landfill space for disposal. Training may involve four to six weeks of incremental moves, such as moving and elevating the litter box until it is near the toilet, as well as employing an adapter such as a bowl or small box to suspend the litter above the toilet bowl.[58] Several kits and other aids are marketed to help toilet-train cats. When training is complete, the cat uses the toilet by squatting on the toilet seat over the bowl.

Domesticated varieties

The list of cat breeds is quite large: most cat registries actually recognize between 30 and 40 breeds of cats, and several more are in development, with one or more new breeds being recognized each year on average, having distinct features and heritage. The owners and breeders of show cats compete to see whose animal bears the closest resemblance to the "ideal" definition & standard of the breed (see selective breeding). Because of common crossbreeding in populated areas, many cats are simply identified as belonging to the homogeneous breeds of domestic longhair and domestic shorthair, depending on their type of fur. In the United Kingdom and Australia, non-purebred cats are referred in slang as moggies (derived from "Maggie", short for Margaret, reputed to have been a common name for cows and calves in 18th century England and latter applied to housecats during the Victorian era).[59] In the United States, a non-purebred cat is sometimes referred to in slang as a barn or alley cat, even if it is not a stray. Cats come in a variety of colors and patterns. These are physical properties and should not be confused with a breed of cat. Some original cat breeds that have a distinct phenotype that is the main type occurring naturally as the dominant domesticated cat type in their region of origin are sometimes considered as subspecies and also have received names as such in nomenclature, although this is not supported by feline biologists. Some of these cat breeds are:

- F. catus anura - the Manx

- F. catus siamensis - the Siamese

- F. catus cartusenensis - the Chartreux

- F. catus angorensis - the Turkish Angora

Coat patterns

Cat coat genetics can produce a variety of coat patterns. Some of the most common are:

- Bicolor, Tuxedo and Van

- This pattern varies between the tuxedo cat which is mostly black with a white chest, and possibly markings on the face and paws/legs, all the way to the Van pattern (so named after the Lake Van area in Turkey, which gave rise to the Turkish Van breed), where the only colored parts of the cat are the tail (usually including the base of the tail proper), and the top of the head (often including the ears). There are several other terms for amounts of white between these two extremes, such as Harlequin or jellicle cat. Bicolor cats can have as their primary (non-white) color black, red, any dilution thereof and tortoiseshell (see below for definition).

- Tabby cat

- Striped, with a variety of patterns. The classic "blotched" tabby (or "marbled") pattern is the most common and consists of butterflies and bullseyes. The "mackerel" or "striped" tabby is a series of vertical stripes down the cat's side (resembling the fish). This pattern broken into spots is referred to as a "spotted" tabby. Finally, the tabby markings may look like a series of ticks on the fur, thus the "ticked" tabby, which is almost exclusively associated with the Abyssinian breed of cats. The worldwide evolution of the cat means that certain types of tabby are associated with certain countries; for instance, blotched tabbies are quite rare outside NW Europe, where they are the most common type.

- Tortoiseshell and Calico

- This cat is also known as a Calimanco cat or Clouded Tiger cat, and by the nickname "tortie." In the cat fancy, a tortoiseshell cat is randomly patched over with red (or its dilute form, cream) and black (or its dilute blue) mottled throughout the coat. Additionally, the cat may have white spots in its fur, which make it a "tortoiseshell and white" cat or, if there is a significant amount of white in the fur and the red and black colors form a patchwork rather than a mottled aspect, the cat will be called a "calico." All calicos are tortoiseshell (as they carry both black and red), but not all tortoiseshells are calicos (which requires a significant amount of white in the fur and patching rather than mottling of the colors). The calico is also sometimes called a "tricolor cat." The Japanese refer to this pattern as mi-ke (meaning "triple fur"), while the Dutch call these cats lapjeskat (meaning "patches cat"). A true tricolor must consist of three colors: a reddish color, dark or light; white; and one other color, typically a brown, black or blue.[60] Both tortoiseshell and calico cats are typically female because the coat pattern is the result of differential X chromosome inactivation in females (which, as with all normal female mammals, have two X chromosomes). Conversely, cats where the overall color is ginger (orange) are commonly male (roughly in a 3:1 ratio). In a litter sired by a ginger tom, the females will be tortoiseshell or ginger. Male tortoiseshells can occur as a result of chromosomal abnormalities (often linked to sterility) or by a phenomenon known as chimericism, where two early stage embryos are merged into a single kitten.

- Colorpoint

- The colorpoint pattern is most commonly associated with Siamese cats, but may also appear in any domesticated cat. A colorpointed cat has dark colors on the face, ears, feet, and tail, with a lighter version of the same color on the rest of the body, and possibly some white. The exact name of the colorpoint pattern depends on the actual color, so there are seal points (dark brown), chocolate points (warm lighter brown), blue points (dark gray), lilac or frost points (silvery gray-pink), red or flame points (orange), and tortie (tortoiseshell mottling) points, among others. This pattern is the result of a temperature sensitive mutation in one of the enzymes in the metabolic pathway from tyrosine to pigment, such as melanin; thus, little or no pigment is produced except in the extremities or "points," where the skin is slightly cooler. For this reason, colorpointed cats tend to darken with age as bodily temperature drops; also, the fur over a significant injury may sometimes darken or lighten as a result of temperature change.

- The tyrosine pathway also produces neurotransmitters, thus mutations in the early parts of that pathway may affect not only pigment, but also neurological development. This results in a higher frequency of cross-eyes among colorpointed cats, as well as the high frequency of cross-eyes in white tigers.

- White cats

- True albinism (a mutation of the tyrosinase gene) is quite rare in cats. Much more common is the appearance of white coat color due to a lack of melanocytes in the skin. A higher frequency of deafness in white cats is due to a reduction in the population and survival of melanoblast stem cells, which in addition to creating pigment producing cells, develop into a variety of neurological cell types. White cats with one or two blue eyes have a particularly high likelihood of being deaf.

Body types

Cats can also come in several body types, ranging between two extremes:

- Oriental

- Not a specific breed, but any cat with an elongated slender build, almond-shaped eyes, long nose, large ears (the Siamese and Oriental Shorthair breeds are examples of this).

- Cobby

- Any cat with a short, muscular, compact build, roundish eyes, short nose, and small ears. Persian cats and Exotic cats are two prime examples of such a body type.

Feral cats

Feral cats may live alone, but most are found in large groups called feral colonies with communal nurseries, depending on resource availability. Most abandoned cats probably have little alternative to joining a feral colony. Some feral cat colonies are found in large cities such as around the Colosseum and Forum Romanum in Rome. The Roman cats are not truly feral because they are partly fed and vetted by the local authority. Because cats are adaptable, those in residential areas know that if they are friendly to humans they need not worry about food or shelter. Some urban "stray" cats have many houses/humans to support them.

Although cats are adaptable, feral felines are unable to thrive in extreme cold and heat, and with a very high protein requirement, few find adequate nutrition on their own in cities. They are often killed by dogs, coyotes, and automobiles. However, there are thousands of volunteers and organizations that trap these unadoptable feral felines, neutering them, immunize the cats against rabies and feline leukemia, and treat them with long-lasting flea products. Before release back into their feral colonies, the attending veterinarian often nips the tip off one ear to mark the feral as neutered and inoculated, since these cats will more than likely find themselves trapped again. Volunteers continue to feed and give care to these cats throughout their lives, and not only is their lifespan greatly increased, but behavior and nuisance problems, due to competition for food, are also greatly reduced.

Environmental effects

Feral cats are thought to be a major predator of Hawaiian coastal and forest habitats, and are one species among many responsible for the decline of endemic forest bird species as well as seabirds like the Wedge-tailed Shearwater.[61] In one study of 56 cats' feces, the remains of 44 birds were found, 40 of which were endemic species.[62]

In the Southern Hemisphere there are many landmasses including Australia where cat species have never been native, and other placental mammalian predators were rare or absent. Native species there tend to be more ecologically vulnerable and behaviorally "naive" to predation by feral cats. Feral cats have had serious effects on these wildlife species and have played a leading role in the endangerment and extinction of many of them. In Australia a large quantity of native birds, lizards and small marsupials are taken every year by feral cats, and feral cats have played a role in driving some small marsupial species to extinction. Some organizations in Australia are now going to effort of creating fenced islands of habitat for endangered species that are free of feral cats and foxes.[63]

Ethical and humane concerns over feral cats

There are two divergent views about the relationship of cats with the environment. The first argues that the environmental impact of feral cat programs and of indoor/outdoor cats is a subject of debate. Part of this stems from humane concern for the cats, and part stems from concerns about cat predation on endangered species. The amount of ecological damage done by indoor/outdoor cats depends on local conditions. As suggested above, the most severe effect occurs to island ecologies. Environmental concerns may be minimal in most of the UK where cats are an established species and few to none of the local prey species are endangered. Pet owners can contact veterinarians, ecological organizations, and universities for opinions about whether local conditions are suitable for outdoor cats. Additional concerns include potential dangers from larger predators and infectious diseases. Coyotes kill large numbers of housecats in the Southwestern United States, even in urban zones. FELV (feline leukemia), FIV (feline immunodeficiency virus), or rabies may be present in the area. If faced with conflicting evidence, the safe choice is to keep a cat indoors.

Cats present a risk of overpopulation, as well. According to the Humane Society of the United States, 3–4 million cats and dogs are euthanized each year in the United States and many more are confined to cages in shelters because there are significantly more animals being born than there are homes. Neutering pets helps keep the overpopulation down. A study in 1992 found that in the USA, 12,893 (29.4%) of pets, 26.9% of dogs and 32.6% of cats were sterilized.[64] Local humane societies, SPCAs, and other animal protection organizations urge people to neuter their pets and to adopt from shelters instead of purchasing elsewhere.

Etymology and taxonomic history

Scientific classification

The domestic cat was first classified as Felis catus by Carolus Linnaeus in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae of 1758.[65][2] However, some contemporary studies have revealed evidence that domestic cats may be conspecific with (belong to the same species as) the Wildcat,[65] classified as Felis silvestris by Schreber in 1777.[66] This has resulted in mixed usage of the terms. The domestic cat is sometimes considered to be a subspecies, F. s. catus, of the species F. silvestris.[4] Wildcats have also been referred to as various subspecies of F. catus,[66] but in 2003, Opinion 2027 of the ICZN fixed the name for Wildcats as F. silvestris.[67] The predominant usage for the domestic cat remains to be F. catus, treating it as a separate species and following the convention of using the earliest (the senior) synonym proposed.

Johann Christian Polycarp Erxleben classified the domesticated cat as Felis domesticus in his Anfangsgründe der Naturlehre and Systema regni animalis of 1777. This name, and its variants Felis catus domesticus and Felis silvestris domesticus, are often seen, but they are not valid scientific names under the rules of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature.

Nomenclature

A group of cats is referred to as a clowder, a male cat is called a tom (or a gib, if neutered), and a female is called a queen. The male progenitor of a cat, especially a pedigreed cat, is its sire, and its female progenitor is its dam. An immature cat is called a kitten (which is also an alternative name for young rats, rabbits, hedgehogs, beavers, squirrels and skunks). In medieval Britain, the word kitten was interchangeable with the word catling. A cat whose ancestry is formally registered is called a pedigreed cat, purebred cat, or a show cat (although not all show cats are pedigreed or purebred). In strict terms, a purebred cat is one whose ancestry contains only individuals of the same breed. A pedigreed cat is one whose ancestry is recorded, but may have ancestors of different breeds (almost exclusively new breeds; cat registries are very strict about which breeds can be mated together). Cats of unrecorded mixed ancestry are referred to as domestic longhairs and domestic shorthairs or commonly as random-bred, moggies, mongrels, mutt-cats or alley cats. The ratio of pedigree/purebred cats to random-bred cats varies from country to country. However, generally speaking, purebreds are less than ten percent of the total Feline population.[68]

Etymology

The word cat derives from Old English catt, which belongs to a group of related words in European languages, including Welsh cath, Spanish gato, Basque katu, Byzantine Greek kátia, Old Irish cat, German Katze, and Old Church Slavonic kotka. The ultimate source of all these terms is Late Latin catus, cattus, catta "domestic cat", as opposed to feles "European wildcat". It is unclear whether the Greek or the Latin came first, but they were undoubtedly borrowed from an Afro-Asiatic language akin to Nubian kadís and Berber kaddîska, both meaning "wildcat".[69] This term was either cognate with or borrowed from Late Egyptian čaus "jungle cat, African wildcat" (later giving Coptic šau "tomcat"[70]), itself from earlier Egyptian tešau "female cat"[71] (vs. miew "tomcat"[72]).

The term puss (as in pussycat) may come from Dutch poes or from Low German Puuskatte, dialectal Swedish kattepus, or Norwegian pus, pusekatt, all of which primarily denote a woman and, by extension, a female cat.[73]

History and mythology

Cats have been kept by humans since at least ancient Egypt, where Bast in cat form was goddess of the home, the domesticated cat, protector of the fields and home from vermin infestations, and sometimes took on the warlike aspect of a lioness. The first domesticated cats may have saved early Egyptians from many rodent infestations and likewise, Bast developed from the adoration for her feline companions. She was the daughter of the sun god Ra and played significant role in Ancient Egyptian religion. It has been speculated that cats resident in Kenya's Islands in the Lamu Archipelago may be the last living direct descendants of the cats of ancient Egypt.[74]

Several ancient religions believed that cats are exalted souls, companions or guides for humans, that they are all-knowing but are mute so they cannot influence decisions made by humans. In Japan, the Maneki Neko is a cat that is a symbol of "good fortune". Although there are no sacred species in Islam, it is said by some writers that Muhammad had a favorite cat, Muezza.[75] It is said he loved cats so much that "he would do without his cloak rather than disturb one that was sleeping on it".[76]

Freyja — the goddess of love, beauty, and fertility in Norse mythology — is depicted as riding a chariot driven by cats.

There are also negative superstitions about cats in many cultures. An example would be the belief that a black cat "crossing your path" leads to bad luck, or that cats are witches' familiars used to augment a witch's powers and skills. This belief led to the widespread extermination of cats in Europe in medieval times. Killing the cats aggravated epidemics of the Black Plague in places where there were not enough cats left to keep rat populations down. The plague was spread by fleas carried by infected rats.

An exaggerated fear of cats is known as ailurophobia.

Nine lives

According to a myth in many cultures, cats have nine (or sometimes seven) lives. The myth is attributed to the natural suppleness and swiftness cats exhibit to escape life-threatening situations.[77] Also lending credence to this myth is that falling cats often land on their feet because of an inbuilt automatic twisting reaction and are able to twist their bodies around to land feet first, though they can still be injured or killed by a high fall.[78]

See also

- Ailurophobia

- Cat breed

- Cat Fanciers' Association

- Cat genetics

- Cat intelligence

- Cat meat

- Cat pheromone

- Cat play and toys

- Category:Cat types

- Farm cat

- List of cat breeds

- List of cats

- List of fictional cats

- Sex organ of cat

- Lolcat

References

- ↑ Wozencraft, W. C. (16 November 2005). Wilson, D. E., and Reeder, D. M. (eds). ed.. Mammal Species of the World (3rd edition ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Linnaeus, Carolus (1766) [1758] (in (Latin)). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae: secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. 1 (12th edition ed.). Holmiae (Laurentii Salvii). p. 62. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k99004c/f62.chemindefer. Retrieved on 2008-04-02.

- ↑ ITIS. "ITIS Standard Report Page: Felis catus domestica".

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Driscoll, Carlos A. et al (2007-07-27). "The Near Eastern Origin of Cat Domestication" (PDF). Science 1: e3. doi:. PMID 17600185. http://www.mobot.org/plantscience/resbot/repr/add/domesticcat_driscoll2007.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-04-02.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Oldest Known Pet Cat? 9500-Year-Old Burial Found on Cyprus". National Geographic News (2004-04-08). Retrieved on 2007-03-06.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Meows Mean More To Cat Lovers". Channel3000.com. Retrieved on 2006-06-14.

- ↑ "Cat Diversity by National Geographic". MySpaceTV. Retrieved on 2008-11-22.

- ↑ Wade, Nicholas (2007-06-29). "Study Traces Cat's Ancestry to Middle East", 'The New York Times'. Retrieved on 2008-04-02.

- ↑ "DWARF, MIDGET AND MINIATURE CATS". Retrieved on 2007-03-06.

- ↑ Cat World (2008). Cat World Records: Heaviest Cat. Retrieved on 2008-07-30 from http://www.cat-world.com.au/CatRecords.htm.

- ↑ Moore, Glenda (2008). Those Amazing Cats. CatStuff. Retrieved on 2008-07-30 from http://www.xmission.com/~emailbox/records.htm.

- ↑ http://www.cat-world.com.au/CatRecords.htm retrieved on 2008/29/11

- ↑ "Cat Skeleton". Archived from the original on 2006-12-06. Retrieved on 2006-12-12.

- ↑ "At Home: Care / Health: Understanding Cats". Retrieved on 2005-08-15.

- ↑ Armes, Annetta F. (1900-12-22). "Outline of Cat Lessons". The School Journal LXI: 659. http://books.google.com/books?id=-_gBAAAAYAAJ. Retrieved on 2007-11-12.

- ↑ "Vaccinate Your Cat at Home". Retrieved on 2006-10-18.

- ↑ "The Cat Comes Back". Retrieved on 2006-10-18.

- ↑ "How to Give Subcutaneous Fluids to a Cat". Retrieved on 2006-10-18.

- ↑ "Scruffing your dog or cat". Retrieved on 2008-02-26.

- ↑ Strain, G.M.. "How Well Do Dogs and Other Animals Hear?". Louisiana State University. Retrieved on 2007-05-15.

- ↑ "The Nose Knows". About.com. Retrieved on 2006-11-29.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Li, Xia; Weihua Li, Hong Wang, Jie Cao, Kenji Maehashi, Liquan Huang, Alexander A. Bachmanov, Danielle R. Reed, Véronique Legrand-Defretin, Gary K. Beauchamp, Joseph G. Brand (July 2005). "Pseudogenization of a Sweet-Receptor Gene Accounts for Cats' Indifference toward Sugar". PLOS Genetics (Public Library of Science) 1 (1): e3. doi:.

- ↑ Animal Doctor (July 9, 2002). "Dear Dr. Fox". The Washington Post, p. C10.

- ↑ Ring, Ken and Romhany, Paul (1999-08-01). Pawmistry: How to Read Your Cat's Paws. Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press. pp. 10. ISBN 1-58008-111-8.

- ↑ "Normal Values For Dog and Cat Temperature, Blood Tests, Urine and other information in ThePetCenter.com". Retrieved on 2005-08-01.

- ↑ Nie W, Wang J, O'Brien PC, et al (2002). "The genome phylogeny of domestic cat, red panda and five mustelid species revealed by comparative chromosome painting and G-banding". Chromosome Res. 10 (3): 209–22. doi:. PMID 12067210.

- ↑ Zoran DL (2002). "The carnivore connection to nutrition in cats" (PDF). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 221 (11): 1559–67. doi:. http://www.catinfo.org/zorans_article.pdf.

- ↑ "Plants and Your Cat". The Cat Fanciers' Association, Inc.. Retrieved on 2007-05-15.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Substances That Are Poison to Pets". Judy's Health Cafe.com. Retrieved on 2007-01-18.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 30.6 "Toxic to Cats". Vetinfo4Cats. Retrieved on 2007-01-18.

- ↑ Allen AL (2003). "The diagnosis of acetaminophen toxicosis in a cat". Canadian Veterinary Journal 44 (6): 509–10. PMID 12839249. http://www.pubmedcentral.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=12839249.

- ↑ Villar D, Buck WB, Gonzalez JM (1998). "Ibuprofen, aspirin and acetaminophen toxicosis and treatment in Dogs and Cats". Vet Hum Toxicol 40 (3): 156–62. PMID 9610496.

- ↑ Camille DeClementi; Keith L. Bailey, Spencer C. Goldstein, and Michael Scott Orser (December 2004). "Suspected toxicosis after topical administration of minoxidil in 2 cats". Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care 14 (4): 287–292. doi:.

- ↑ "Minoxidil Warning". ShowCatsOnline.com. Archived from the original on 2007-01-03. Retrieved on 2007-01-18. "Very small amounts of Minoxidil can result [in] serious problems or death"

- ↑ Rousseaux CG, Smith RA, Nicholson S (1986). "Acute Pinesol toxicity in a domestic cat". Vet Hum Toxicol 28 (4): 316–7. PMID 3750813. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=3750813&dopt=Abstract.

- ↑ "Antifreeze Warning". The Cat Fanciers' Association, Inc.. Retrieved on 2007-05-15.

- ↑ Cat Guide: Adolescence and Sexual Maturity Animal Planet

- ↑ E. Levine; P. Perry, J. Scarlett, K.A. Houpt (2005). "Intercat aggression in households following the introduction of a new cat" (PDF). Applied Animal Behaviour Science (90): 325–336. doi:. http://faculty.washington.edu/jcha/330_cats_introducing.pdf.

- ↑ Crowell-davis, S.L.; Curtis, T.M.; Knowles, R.J. (2004). "Social organization in the cat: a modern understanding". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 6 (1): 19–28. doi:. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1098612X0300127X. Retrieved on 2008-05-21.

- ↑ Poirier FE, Hussey LK (1982). "Nonhuman Primate Learning: The Importance of Learning from an Evolutionary Perspective" (– Scholar search). Anthropology & Education Quarterly 13 (2): 133–148. doi:. http://www.jstor.org/view/01617761/sp050045/05x1830j/0.

- ↑ "Minnesota's killer kitties: Minnesota DNR". Fish & Wildlife Today. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (1998-02-02). Retrieved on 2008-11-22.

- ↑ Leyhausen, Paul (1978). Cat Behavior: The Predatory and Social Behavior of Domestic and Wild Cats. ISBN 978-0824070175.

- ↑ "Why Do Cats Like High Places?". Drs. Foster & Smith, Inc.. Dr. Holly Nash, DVM, MS.

- ↑ "Falling Cats". Retrieved on 2005-10-24.

- ↑ Huy D. Nguyen. "How does a Cat always land on its feet?". Georgia Tech University, School of Medical Engineering. Retrieved on 2007-05-15.

- ↑ Veterinary & Aquatic Services Department. "High-Rise Syndrome: Cats Injured Due to Falls". Drs. Foster & Smith, Inc..

- ↑ Williams, Robyn (7 November 1999). "The Effect of Domestic Cats on Australian Wildlife". Retrieved on 2007-05-26.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions about Turkish Van Cats". Swimmingcats.com. Retrieved on 2008-11-22.

- ↑ Muir, Hazel (2004-04-08). "Ancient remains could be oldest pet cat", New Scientist. Retrieved on 2007-11-23.

- ↑ Walton, Marsha (April 9, 2004). "Ancient burial looks like human and pet cat", CNN. Retrieved on 2007-11-23.

- ↑ "Feline Statistics". Retrieved on 2005-08-15.

- ↑ "Spay and Neuter Your Pet Cats".

- ↑ "Dealing with cat allergies" (PDF). animaltrustees.org. Archived from the original on 2007-06-04.

- ↑ "Scratching or clawing in the house". Retrieved on 2005-08-14.

- ↑ "Suspected bentonite toxicosis in a cat from ingestion of clay cat litter". Retrieved on 2005-09-10.

- ↑ "Parasite in cats killing sea otters", NOAA magazine, National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (2003-01-21). Retrieved on 2007-11-24.

- ↑ Brown-Martin, Darcy (March 2007). "Monterey Bay’s sea otter sleuth". Viamagazine.com. Retrieved on 2008-11-22.

- ↑ "A Step-By-Step Guide on How To Train Your Cat to Use the Human Toilet". The Toilet Trained Cat. Retrieved on 2008-11-22.

- ↑ "Moggie". Worldwidewords.org. Retrieved on 2007-05-15.

- ↑ "Torties, Calicos and Tricolor cats". Retrieved on 2005-10-24.

- ↑ ARTICLES ON HAWAIIAN BIRDS AND BIRDWATCHING AND OTHER PACIFIC WILDLIFE

- ↑ "Introduced Species in Hawaii (Senior Seminar 2002)". Earlham college, Department of Biology (2002). Retrieved on 2007-05-15.

- ↑ Community awareness and involvement in the conservation of our unique mammal emblem, Project Numbat

- ↑ Jane C. Mahlow, DVM, MS. "Estimation of the proportions of dogs and cats that are surgically sterilized". www.spayusa.org, summarizing J Am Vet Med Assoc 1992;215;640–643. Retrieved on 2007-05-15.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Wozencraft, W. C. (16 November 2005). Wilson, D. E., and Reeder, D. M. (eds). ed.. Mammal Species of the World (3rd edition ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 534–535. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3/browse.asp?id=14000031.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Wozencraft, W. C. (16 November 2005). Wilson, D. E., and Reeder, D. M. (eds). ed.. Mammal Species of the World (3rd edition ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 536–537. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3/browse.asp?id=14000057.

- ↑ ICZN (2003-03-31). "Opinions". Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature (International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature) 60. http://www.iczn.org/BZNMar2003opinions.htm#opinion2027. Retrieved on 2008-04-02.

- ↑ ASPCA Complete Guide to Cats by James R. Richards,, DVM

- ↑ "Cat". The Online etymology dictionary. Retrieved on 2007-05-15.

- ↑ Crum, Walter Ewing. A Coptic Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1939: 601 [1]

- ↑ "Le chat: origines et étymologie." Chat et compagnie. 2006. [2]

- ↑ SenenAnep Meritamen. "English to Egyptian Dictionary." posted August 29, 2004. Ancient Worlds. AncientWorlds LLC, 2002 [3].

- ↑ Webster's Encyclopedic Unabridged Dictionary of the English Language. New York: Gramercy Books, 1996: 1571.

- ↑ Couffer, Jack (1998). The Cats of Lamu. New York: The Lyons Press. ISBN 1558216626.

- ↑ Geyer, Georgie Anne (2004). When Cats Reigned Like Kings: On the Trail of the Sacred Cats.

- ↑ Minou Reeves. Muhammad in Europe. New York University (NYU) Press. pp. p.52.

- ↑ "Cat Myths, Misinformation and Untruths". Best-cat-art.com. Retrieved on 2008-11-22.

- ↑ The ASPCA Warns About High-Rise Falls by Cats. About.com

External links

Anatomy

Articles

- Biodiversity Heritage Library bibliography for Felis catus

- Cat behavior explained

- Catpert. The Cat Expert - Cat articles

- Choosing a cat - article at Citizendium

- American Association of Feline Practitioners

- Cat Genome Project at the US The National Cancer Institute

- Cat Vaccination and Health Care Schedule

- Cornell Feline Health Center

- Feline Behavior Guidelines An AAFP publication

- Feline Medical & Behaviour Database (large number of short articles)

- Onions are Toxic to Cats

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||