Military of Switzerland

| Military of Switzerland |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Leadership | |

| Minister of Defense | Swiss Federal Council Samuel Schmid |

| Military age | 17-34 |

| Conscription | 19-34 years of age obligatorily 36 for subaltern officers, 52 for staff officers and higher |

| Available for military service |

1,707,694 males, age 19–49 (2005 est.), 1,662,099 females, age 19–49 (2005 est.) |

| Fit for military service |

1,375,889 males, age 19–49 (2005 est.), 1,342,945 females, age 19–49 (2005 est.) |

| Reaching military age annually |

46,319 males (2005 est.), 43,829 females (2005 est.) |

| Expenditures | |

| Budget | 4.91 billions CHF(approx. 4 billion $)(FY05[1]) |

| Percent of GDP | 1.06% (2005 est.) |

The military of Switzerland, officially known as the Swiss Armed Forces, is a unique institution somewhere between a militia and a regular army. It is equipped with mostly modern, sophisticated, and well-maintained weapons systems and equipment.

History

The Swiss army originated from the cantonal troops of the Old Swiss Confederacy, called upon in cases of external threats by the Tagsatzung or by the canton in distress. In the federal treaty of 1815, the Tagsatzung prescribed cantonal troops to put a contingent of 2% of the population of each canton at the federation's disposition, amounting to a force of some 33,000 men. The cantonal armies were converted into the federal army (Bundesheer) with the constitution of 1848. From this time, it was illegal for the individual cantons to declare war or to sign capitulations or peace agreements. Paragraph 13 explicitly prohibited the federation from sustaining a standing army, and the cantons were allowed a maximum standing force of 300 each (not including the Landjäger corps, a kind of police force). Paragraph 18 declared the obligation of every Swiss citizen to serve in the federal army if conscripted (Wehrpflicht), setting its size at 3% of the population plus a reserve of one and one half that number, amounting to a total force of some 80,000.

The first complete mobilization, under the command of Hans Herzog, was triggered by the Franco-Prussian War in 1871. In 1875, the army was called in to crush a strike of workers at the Gotthard tunnel. Four workers were killed and 13 were severely wounded.

Paragraph 19 of the revised constitution of 1874 extended the definition of the federal army to every able-bodied citizen, swelling the size of the army at least in theory from below 150,000 to more than 700,000, with population growth during the 20th century rising further to some 1.5 million, the second largest armed force per capita after the Israeli Defence Forces.

A major maneuver commanded in 1912 by Ulrich Wille, a reputed germanophile, convinced visiting European heads of state, in particular Kaiser Wilhelm II, of the efficacy and determination of the Swiss defense. Wille subsequently was put in command of the second complete mobilization, and Switzerland escaped invasion in the course of World War I. Wille also ordered the suppression of the general strike (Landesstreik) of 1918 with military force. Three workers were killed, and a rather larger number of soldiers died of the Spanish flu during mobilization. In 1932, the army was called to suppress an anti-fascist demonstration in Geneva. The troops shot 13 unarmed demonstrators, wounding another 65. This incident permanently damaged the army's reputation, leading to persisting calls for its abolition among left wing politicians. In both the 1918 and the 1932 incidents, the troops deployed were consciously selected from rural regions such as the Berner Oberland, fanning the enmity between the traditionally conservative rural population and the urban working class. The third complete mobilization of the army took place during World War II under the command of Henri Guisan (see also Switzerland during the World Wars). The Patrouille des Glaciers race, created to test the abilities of soldiers, was created during the war.

In 1989, the status of the army as a national icon was shaken by a popular initiative aiming at its complete dissolution (see: Group for a Switzerland without an Army) receiving 35.6% support. This triggered a series of reforms, and in 1995, the number of troops was reduced to 400,000 ("Armee 95"). Article 58.1 of the 1999 constitution repeats that the army is "in principle" organized as a militia, implicitly allowing a small number of professional soldiers. A second initiative aimed at the army's dissolution in 2001 received a mere 21.9% support. Nevertheless, the army was shrunk again in 2004, to 220,000 men ("Armee XXI"), including the reserves.

Military services

On May 18, 2003, Swiss voters approved the military reform project "Army XXI" to drastically reduce the size of the Swiss Army. Starting in January 2004, the 524,000-strong militia was pared down to 220,000 conscripts, including 80,000 reservists. The defence budget of SFr 4.3 billion ($3.1 billion) was trimmed by SFr 300 million and some 2,000 jobs are expected to be shed between 2004 and 2011.

The armed forces consist of a small nucleus of about 3,600 professional staff, half of whom are either instructors or staff officers, with the rest being conscripts or volunteers. All able-bodied Swiss males aged between 19 and 31 must serve, and although entry to recruit school may be delayed due to senior secondary school, it is no longer possible to postpone it for university studies. About one third is excluded for various reasons, and these either serve in Civil Protection or Civilian Service.

Recruits are generally instructed in their native language; however, the small number of Romansch-speaking recruits are instructed in German. Some smaller companies recruit people from all four language regions, making it difficult to always have the teachers with the matching skills available. Generally, language differences cause very few problems, since at the age of their recruitement, all Swiss people should have a basic understanding of at least two of the spoken languages in Switzerland.

For women, military service is voluntary, and they can join all services, including combat units. About 2,000 women already serve in the army but, until the "Armee XXI" reform, were not allowed to use weapons for purposes other than self-defence. Since the reform, women can take on any position within the armed forces. Once decided to serve, they have the same rights and duties as their male colleagues.

Due to the small size of the Swiss Air Force, competition to become an aircraft pilot is extremely high. Candidate pilots and parachutists have to start training in their own free time from the age of 16, well before recruitment. However, if candidates appear at recruitment with a certificate showing completion of preliminary training, they are practically guaranteed that duty, provided they pass the following selection during service. Aspiring pilots must however first complete basic training in a regular unit and complete officer school before entering into a unit of candidate pilots.

The army has established a new category of soldiers, called "single-term conscripts," (Durchdiener) who volunteer to serve a single term of 300 days of active duty. The total number of single-term conscripts cannot exceed 15% of a year's draft, and these volunteers can only serve in certain branches of the military. The rest continue to follow the traditional Swiss model of serving from 18 to 21 weeks at first and then doing a service, called repetition course, of three weeks (four for officers) per year until they serve the required number of days or reach the age of 26. After completion of their service days, they become reservists until they reach the age of 32.

Soldiers can be required to advance in rank, usually to Sergeant, Sergeant Major, Fourier or Lieutenant. This is often required of Italian-speaking soldiers, because they make up a minority in the population and the armed forces, and there is a need for Italian-speaking officers. A higher rank typically entails a longer service time, which results in some wishing to avoid promotion.

With the new reform, if a soldier is promoted to sergeant, during the base instruction he can no longer advance to lieutenant and onwards, as they now follow two separate branches of development. However, many soldiers still prefer this, mainly because of a shorter service time (compared to lieutenants) but also because they have a more active, up-close role with the other troops as regular soldiers, instead of managing from a distance as officers. During repetition courses, however, there is the possibility for soldiers and non commissioned officers to advance either to NCO's or to officer grades.

Men who want to apply for service in the Swiss Guard need to have completed their basic military service in Switzerland, and are also required to be Catholic.

Being landlocked, Switzerland does not have a navy, but it does maintain a fleet of military patrol boats, armed with two 12.7mm machine guns, numbering 10 in 2006. They patrol the Swiss lakes: Lake Geneva, Lake Lucerne, Lake Lugano, Lake Maggiore and Lake Constance. These boats are sometimes humorously referred to as the "Swiss Navy".

Defence ministers

Members of the Federal Council heading the "Federal Department of Defence, Civil Protection and Sports" (formerly "Federal Military Department") is the Swiss defence minister:

|

|

Ranks

Rank designations in German, French, Italian and English with abbreviations and corresponding NATO codes:

- Enlisted

- Rekrut (Rekr) / recrue (recr) / recluta (recl)

- Soldat (Sdt) / soldat (sdt) / soldato (sdt) / Private E-1

- Gefreiter (Gfr) / appointé (app) / appuntato (app) / Private E-2

- Obergefreiter (Obgfr) / appointé-chef (app chef) / appuntato capo / Private First Class

- Non-commissioned officers

- Korporal (Kpl) / caporal (cpl) / caporale (cpl) / Corporal

- Wachtmeister (Wm) / sergent (sgt) / sergente (sgt) / Sergeant

- Oberwachtmeister (Obwm) / sergent-chef (sgt chef) / sergente capo / Sergeant First Class

- Feldwebel (Fw) / sergent-major (sgtm) / sergente maggiore / Sergeant Major

- Fourier (Four) / fourrier (four) / furiere / Quartermaster Sergeant

- Hauptfeldweibel (Hptfw) / sergent-major chef (sgtm chef) / sergente maggiore capo / Chief Sergeant Major

- Adjutant Unteroffizier (Adj Uof) / adjudant sous-officier (adj sof) / aiutante sottoufficiale / Warrant Officer

- Stabsadjutant (Stabsadj) / adjudant d’état-major (adj EM) / aiutante di stato maggiore / Staff Warrant Officer (bn)

- Hauptadjutant (Hptadj) / adjudant-major (adj maj) / aiutante maggiore / Master Warrant Officer (bde)

- Chefadjutant (Chefadj) / adjudant-chef (adj chef) / aiutante capo / Chief Warrant Officer (div)

- Subaltern officers

- Leutnant (Lt) / lieutenant (lt) / tenente (ten) / Second Lieutenant OF-1

- Oberleutnant (Oblt) / premier-lieutenant (plt) / primo tenente (Iten) / First Lieutenant OF-1

- Captain

- Hauptmann (Hptm) / capitaine (cap) / capitano (cap) / Captain OF-2

- Staff officers

- Major (Maj) / major (maj) / maggiore (magg) / Major OF-3

- Oberstleutnant (Oberstlt) / lieutenant-colonel (lt col) / tenente colonnello / Lieutenant Colonel OF-4

- Oberst / colonel (col) / colonnello / Colonel OF-5

- Higher staff officers

- Brigadier (Br) / brigadier / brigadiere / Brigadier General OF-6

- Divisionär (Div) / divisionnaire / divisionario / Major General OF-7

- Korpskommandant (KKdt) / commandant de corps / comandante di corpo / Lieutenant General OF-8

- General / général / generale / General OF-9 (There is normally no General. In time of war or crisis, Parliament elects a General. Only four men have held this rank in Switzerland: Henri Dufour [1847-1848 and 1856-57], Hans Herzog [1871-1872], Ulrich Wille [1914-1918], and Henri Guisan [1939-1945].)

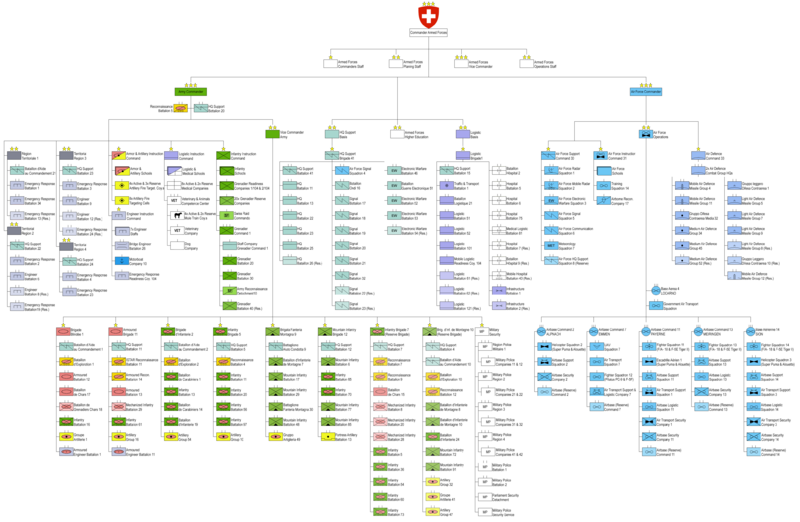

High Command

In peacetime, the armed forces are led by the Chief of the Armed Forces (Chef der Armee), who reports to the head of the Department of Defence and to the Federal Council as a whole. The current Chief of the Armed Forces is Major-General (Divisionär) André Blattman. Maj-Gen Blattman replaces Lieutenant-General (Korpskommandant) Roland Nef who resigned on July 25, 2008 “following allegations of sexual harassment”[2].

In times of crisis or war, the Federal Assembly elects a General (OF-9) as Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces (Oberbefehlshaber der Armee). There have been four Generals in Swiss history:

- Henri Dufour (1847-1848, Sonderbund war; and 1856-57, Neuchâtel Crisis)

- Hans Herzog (1871-1872, Franco-Prussian War)

- Ulrich Wille (1914-1918, World War I)

- Henri Guisan (1939-1945, World War II)

Officers which would have the title of general in other armies do not bear the title general (OF-8: Commandant de corps, OF-7 Divisionnaire and OF-6 Brigadier), as this title is strictly a wartime designation. The distinctive feature of their rank insignia are traditionally stylized edelweiss (image). However, when Swiss Officers are involved in peacekeeping missions abroad, they often receive temporary ranks that do not exist in the Swiss Army, to put them on an equal footing with foreign officers. For example, the head of the Swiss delegation at the NNSC in Korea (see below) had a rank of major general.

Structure

Intelligence community

The Swiss military department maintains the Onyx intelligence gathering system, similar in concept to the UKUSA's ECHELON system, but at a much smaller scale.

The Onyx system was launched in 2000 in order to monitor both civil and military communications, such as telephone, fax or Internet traffic, carried by satellite. It was completed in late 2005 and currently consists in three interception sites, all based in Switzerland. In a way similar to ECHELON, Onyx uses lists of keywords to filter the intercepted content for information of interest.

On 8 January 2006, the Swiss newspaper Sonntagsblick (Sunday edition of the Blick newspaper) published a secret report produced by the Swiss government using data intercepted by Onyx. The report described a fax sent by the Egyptian department of Foreign Affairs to the Egyptian Embassy in London, and described the existence of secret detention facilities (black sites) run by the CIA in Central and Eastern Europe. The Swiss government did not officially confirm the existence of the report, but started a judiciary procedure for leakage of secret documents against the newspaper on 9 January 2006.

Peacekeeping missions

Switzerland being a neutral country, its army does not take part in armed conflicts in other countries. However, over the years, the Swiss army has been part of several peacekeeping missions around the world.

Mission in Bosnia and Herzegovina (SHQSU)

From 1996 to 2001, The Swiss Army was present in Bosnia and Herzegovina with headquarters in Sarajevo. Its mission, part of the Swiss Peacekeeping Missions, was to provide logistic and medical support to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, OSCE as well as protection duties and humanitarian demining. The mission was named SHQSU standing for Swiss Headquarters Support Unit to BiH. It was composed of 50 to 55 elite Swiss soldiers under contract for 6 to 12 months. None of the active soldiers were armed during the duration of the mission. The Swiss soldiers were recognized among the other armies present on the field by their distinctive yellow beret. The SHQSU is not the same as the more publicized SWISSCOY, which is the Swiss Army Mission to Kosovo.

Mission in Korea (NNSC)

Switzerland is part of the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission (NNSC) which was created to monitor the armistice between North and South Korea. Since the responsibilities of the NNSC have been much reduced over the past few years, only 5 people are still part of the Swiss delegation, located near the Korean DMZ.[3][4][5]

Criticism

There is an organised movement in Switzerland (Group for a Switzerland without an Army) aiming at the abolition of the military. The Swiss have voted twice on such a referendum. The first time was in 1989, when 64.4% of the voters voted in favour of maintaining the Swiss Army. The second vote was in 2001, with 76.8% in favour.

In 1992, after the Swiss government decided to buy F/A-18 jets, they collected about half a million signatures within one month for a referendum. The population decided to buy the jets, with 57.1% voting to approve the project.

The organisation is still active in antimilitaristic work and also in the anti-war movement.

Generally, the army being criticized today by politicians who argue it is trying to save its existence by performing non-military jobs like protecting embassies or providing security services to the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos. This practice is seen to be justified by conservatives when regarding the lack of police forces (Switzerland leased police troops from Germany for the duration of the WEF).

Other criticism targets the planned acquisition of more fighter-jets, in sight of the coming retirement of F-5 Tiger IIs in 2011, and a CASA CN-235 transport aircraft, for example for evacuation purposes. Army critics say that F/A-18 are not needed, and that for humanitarian duties cargo space can be leased for much less money on civilian aircraft.

Conscription

All able-bodied male Swiss citizens are conscripted to the armed forces until the age of 30. In practice, persons who become Swiss citizens after the age of 25 are rarely summoned and instead pay a 3% additional annual income tax. For women the service is voluntary.

Information letter and day

At 17 years of age, male Swiss citizens receive a letter detailing their military obligations. At 18 years of age, they are sent marching orders to present themselves at a nearby barracks for a day of information. They are given presentations explaining the various branches of service and prerequisites for certain positions such as jet pilot (which requires two years of flight school outside of military service). Those wishing to take part in civilian service or weaponless service are instructed to address a letter detailing their intentions to their canton's military authority prior to recruitment.

Conscripts are also issued a service booklet in which the person's attendances or exemptions are recorded. To avoid conflicting with studies or work, they are also asked to pick a time (typically corresponding to spring, summer and autumn periods) most convenient for recruitment and start of service. Typically, a conscript will attend recruitment at 19 years of age and begin service at 20, but may legally postpone recruitment until 23 years of age.

Due to a new military reform enacted in 2005, it is no longer possible to postpone the initial training to finish university, although it is possible to postpone in order to finish high school or equivalent apprenticeships (for example for an aspiring carpenter who might only finish training at 19 or 20). For this reason many people try to get out of military service, so they can attend university immediately after finishing high school. It is possible to split the time in basic training (as recruit) and service (as soldier) which would allow one to start university immediately, the second half must be served at the earliest possible opportunity, usually Christmas break, a time which is usually used to study for exams. Hence, this practice is very hard on the student, and generally not recommended. The successive training weeks can also be postponed, but there is limited scope. In general, men interrupt their work during these weeks.

Recruitment

Recruitment is a two to three day process, typically taking place three to six months before start of service, during which the conscript is given physical and psychological tests to assess his suitability for service. Conscripts are also given the opportunity to present medical certificates from private doctors detailing any physical or mental handicaps they may have. Conscientious objectors also meet with additional psychologists to explain their desire to abstain from regular army service and take part in civilian service instead.

A person may either be found fully capable, in which case army service or civilian service follow, less than capable, in which case civilian protection follows, or incapable, in which case the person is exempted from service and pays a 3% additional annual income tax. A person's starting function is also determined or narrowed down during recruitment.

Army service

60% of conscripted men will carry out regular military service, as opposed to civilian service, civilian protection or service exclusion. Service duration is 260 days for enlisted soldiers, 500 for non-commissioned officers and 600 for officers.

Famously, members of the armed forces keep their rifles and uniforms in their homes for immediate mobilisation, as well as 50 rounds of ammunition in a sealed tin, to be used for self defence while traveling to the mobilisation points, though the ammunition is no longer issued. Additional ammunition is kept at military bases where the militia are supposed to report. Swiss military doctrines are arranged in ways that make this organisation very effective and rapid. Switzerland claims to be able to mobilise the entire population for warfare within 12 hours.

Boot camp

Boot camp lasts 18 or 21 weeks, during which the initial seven weeks are the general basic instructions. Following the initial seven weeks:

- A soldier will have 6 weeks of function-specific basic instructions and 5 or 8 weeks of practical service.

- A corporal will have 3 weeks of function-specific basic instructions, 6 weeks of rank-specific instructions with practical training and 5 to 8 weeks of practical service.

- A sergeant will have 3 weeks of function-specific basic instructions, 19 weeks of rank-specific instructions with practical training and 6 to 9 weeks of practical service.

- A sergeant-major will have 3 weeks of function-specific basic instructions, 20 weeks of rank-specific instructions with practical training and 6 to 9 weeks of practical service.

- A lieutenant will have 3 weeks of function-specific basic instructions, 34 weeks of rank-specific instructions with practical training and 6 to 9 weeks of practical service.

Certain units, regardless of rank, are subject to further variations in training length. Grenadiers are an elite infantry unit with a 25-week boot camp. The Army Reconnaissance Detachment (German, AAD, Armeeaufklärungsdetachement; French, DRA, détachement de reconnaissance) Switzerland's new SAS-type Special Forces unit, which is an all-volunteer professional unit with a rigorous selection process, has 18 months of training following boot camp.

Ongoing service

Following boot camp, a conscript serves for three weeks a year, or more if their service would not be completed by 30 years of age at such a rate.

Ongoing shooting practice

Until 30 years of age, conscripts are required to present themselves with their rifle at a shooting range for target practice. This can be done during most periods of the year and dates and locations (which include certain privately-owned ranges) can be consulted on local billboards. During practice, a box of 20 rounds are fired at a standardized target; if the points amount over 42, this is recorded in the conscript's service booklet, otherwise, additional rounds must be purchased at cost. If the conscript still does not manage to achieve 42 points, he may be required to serve an additional two weeks of complementary training.

Long service

Conscripts so inclined may request to serve their obligatory days in a one-time stint, thereby being freed from ongoing service in following years and only being required to take part in ongoing shooting practice. A maximum 15% of conscripts in any given recruitment session may take part in long service. Soldiers taking part in the long service program serve for 300 days instead of 260 as in regular army service, but are granted one four-day weekend a month. Non-commissioned officers and officers serve 500 and 600 days as usual.

Weaponless service

Those who do not wish to carry a weapon may apply for weaponless service. This is done by writing a motivation letter to their canton's military authority prior to recruitment, and is further discussed during. Many exercises can be completed without a weapon, but some require one for practical purposes, in which case a wooden replacement is used.

Civilian service

Since 1996, conscripts who are found to be sufficiently fit for regular military service, but who object for reasons of conscience, can apply for civilian service by writing their canton's military authority prior to recruitment, and further discussing the matter during. This service consists of various kinds of social services, such as reconstructing cultural sites, helping the elderly and other activities removed from military connotations. Civilian service lasts 390 days, 50% longer than a soldier's regular army service.

Civilian protection

Conscripts found to be sufficiently unfit for regular military service, but not for exemption, take part in civilian protection, where they may be called on to assist the police, fire or health departments, as well as natural disaster relief and crowd control during demonstrations or events with large attendances. On average, a person will undergo two weeks of initial training, followed by two days of service a year.

Conscripts serving in civilian protection pay a 3% additional annual income tax like those exempted from military service. This tax is however lessened depending on the number of days served, and may even be reimbursed past a certain level of service.

Exemption

Conscripts found unfit for either regular army or civilian service, or civilian protection due to physical or mental handicaps or issues are exempted from service and instead pay a 3% additional annual income tax until the age of 30. In practice, persons who become Swiss citizens after the age of 25 are usually likewise exempted.

Voluntary service

Swiss citizens can volunteer for any type of service. The person can initiate the process by writing to their canton's military authority. Service is very similar to obligatory service, with the exceptions of skipping the information day, not being subject to the 3% additional annual income tax and ongoing shooting practice.

Compensation

All personnel are paid a basic salary ranging from 4 Swiss francs a day for a recruit to 30 for a corps commander.[6] This is further supplemented by an additional salary ranging from 5 to 80 Swiss francs for non-commissioned officers or officers undergoing training.

During military service, an employee is further paid a compensation of 80% of his regular salary by the state. Most employers, however, continue to pay the full salary during military service. In this case, the compensation is paid to the employer. Employers cannot fire a person in service by law, although there is no specific provision preventing a conscript from being fired before or after a period of service, other than the catch-all law against wrongful termination.

Students, independents or unemployed persons are further paid an income-loss insurance (German, EO, Erwerbsersatzordnung; French, APG, Allocation pour perte de gain) approximately 10 times the basic salary: 54 for basic soldiers, 97 for non-commissioned and commissioned officers during undergoing training. This "EO" can be further improved to 174 if one has children.[7]

Shelters and fortifications

Swiss building codes require radiation and blast shelters to protect against bombing. There is a bed for 95% of Swiss residents in one of the many shelters. There are also hospitals and command centres in such shelters, aimed at keeping the country running in case of emergencies. Every family or rental agency has to pay a small replacement tax to support these shelters, or alternatively own a personal shelter in their place of residence.[8]

Moreover, tunnels and key bridges are built with tank traps. Tunnels are also primed with demolition charges to be used against invading forces. Permanent fortifications are established in the Alps, as bases from which to retake the fertile valleys after a potential invasion. They include underground air bases which are adjacent to normal runways; the aircraft, crew and supporting material are housed in the caverns. The concept of underground fortifications in the Alps stems from the so-called "Reduit" concept of the World War II. It was intended that if the Axis Powers were to invade Switzerland, they would have to do so at a huge price. The army would barricade itself in the mountains within the fortresses, which would be very difficult to take. However, a significant part of these fortifications have been dismantled between the 1980s and during the "Army 95" reformation. The most important fortifications are located at Saint-Maurice, Gotthard Pass area and Sargans. The fortification on the left side of the Rhône at Saint-Maurice is no longer used by the army since the beginning of the 1990s. The right side (Savatan) is nonetheless still in use.

The Swiss government thought that the aim of an invasion of Switzerland would be to control the economically important transport routes through the Swiss Alps, namely the Gotthard, the Simplon and Great St. Bernard passes, because Switzerland does not possess any significant natural resources. Those who actually served in the Swiss Army during the war never criticised this concept - even if it openly meant that the enemy could take the civilian population in the plains hostage.

Leadership

In contrast to most other comparable Armies, officer candidates are not necessarily career regulars. Instead, until 2004 officers were traditionally selected from the pool of NCOs (non-commissioned officers) and then underwent OCS (officer candidate school, which was and is open to both militia - i.e. officers who also have a civilian job - and future professional officers), five months of intensive training that emphasised small-unit and platoon-sized unit tactics. This system ensured that all officers knew the trade skills of a non-commissioned soldier and mitigated resentment towards officers from NCOs.

This was abolished with the Army XXI reform as a concession to the Swiss economy which was increasingly unhappy about having its future leaders away for two years at a time (the time it took to become an officer until 2004). In the new system, officers-to-be are selected early based on criteria such as leadership potential and education and are sent directly to officer training. This system, which is similar to that employed in most countries of the world, reduces the time needed to train an officer but means that new entries are sometimes seen to lack credibility in the eyes of traditionalists. The new system is under review but remains in force.

To assure a generally high level of military leadership above the rank of first lieutenant, the Army maintains the HKA (Hoehere Kaderschule der Armee) which is responsible for an array of professionally run schools such as BUSA (Berufsunteroffiziersschule der Armee) which runs a program for professional non-commissioned officers, the MILAK (Militaerakademie) which runs a bachelor degree program for professional officers, programs for company and battalion commanders, a number of staff courses, and the General Staff and Command College (Gst S), an elite training program whose graduates leave their former branches and are inducted into the so-called General Staff Corps.

Future general staff officers are selected from the best company commanders and undergo battalion commander training before starting general staff training. Only 30 new trainees are selected per year and even fewer complete the demanding training. Being a general staff officer is a prerequisite for a range of important jobs on Brigade and higher level, such as G2 (chief of intelligence) or G3 (chief of operations).

The ratio of professional versus militia officers is about 1:1. As a rule of thumb, a significant number of senior civil servants and business leaders in Switzerland are general staff officers, and aspiring managers used to be required to become officers by their company, which would give them personnel management skills amongst other things.

Weapon systems

To reduce training and logistics costs, the Swiss military standardises on a few carefully selected types of weapons. For example, Switzerland uses only one rifle model (except for select forces, such as military police, grenadiers etc., who are also trained in the use of Heckler & Koch MP5s, shotguns etc.), the FASS 90, and three types of ground-based anti-aircraft systems, including a Swiss-built and improved version of the Stinger (Swiss army knives are also issued, although they are not considered weapons). In 1993, the Swiss government ordered 34 FA-18 fighter jets from the United States of America, which were subsequently re-built in Switzerland, notably for the electronics. Also, the software supporting the pilot was improved and then sold to the United States of America. Switzerland traditionally depends on itself for supplies and parts, often using non-standard equipment, although this has changed somewhat in recent years.

Small arms

- SIG 550 / Sturmgewehr 90 assault rifle

- SIG 510 / Sturmgewehr 57 battle rifle (previous rifle, rare but still in service)

- SIG P220 semi-automatic pistol

- Brügger & Thomet MP5 submachinegun

- Brügger & Thomet MP9 machine pistol

- Tuma MTE 224 VA machine pistol

- MG3 machine gun

- FN Minimi light machine gun

- HG 85 hand grenade

- Gewehraufsatz 97 40mm grenade launcher

- Remington 870 multipurpose shotgun (known as Mehrzweckgewehr 91)

- Panzerfaust 3 shoulder-launched recoilless anti-tank weapon

- M47 Dragon anti-tank guided rocket, actually being phased out without replacement due to cost-intensive maintenance.

- FIM-92 Stinger shoulder-fired SAM

- Sako TRG-42 8.6 mm anti-personnel sniper rifle (Scharfschützengewehr 04)

- PGM Hecate II 12.7 mm anti-materiel heavy sniper rifle (Gew06)

- MG 710 machine gun / MG55 (still stocked, but neither trained on nor used in rep courses; same as MG3)

Armoured vehicles

- Pz87 LEO WE / variant of Leopard 2 main battle tank (224 in service)[9]

- SPz2000 / CV9030 infantry fighting vehicle (186 in service)

- PzHbz88/95 KAWEST / variant of M109 howitzer self-propelled artillery (224 in service)

- RadSPz Piranha / Mowag Piranha APC

- M113 APC (580 in service)

- MOWAG Eagle armoured patrol vehicle

Aircraft

- Northrop F-5E/F Tiger II (54 in service)[10]

- McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 C/D Hornet (33 in service)

- Pilatus PC-6 Porter (16 in service)

- Pilatus PC-7 Turbo Trainer (38 in service)

- Pilatus PC-9 (11 in service)

- Pilatus PC-21 (6 purchased)

- Eurocopter AS 332 Super Puma

- Eurocopter AS 352 Cougar

- Aérospatiale SA 316 Alouette III (35 in service)

Anti-Aircraft

- Rapier missile (known as "Mobile Lenkwaffen Flugabwehr"; 54 in service)

- Oerlikon 35 mm twin cannon (known as "Flab Kanone 63/90"; 90 in service)

See also

- Swiss Civilian Service

- Gun politics in Switzerland

- Swiss Army knife

- IMESS, the Swiss Future Soldier program.

References

- ↑ http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/de/index/themen/18/03/blank/key/ausgaben_nach_funktionen0/gesamt.html (german) (visited 13.08.2008)

- ↑ “Army chief falls but defence minister to stay”, Swissinfo (July 25th, 2008), retrieved in 2008-09-15

- ↑ Swiss participation to the mission NNSC in Korea

- ↑ Swiss keep watch over fragile peace, on Swissinfo

- ↑ Photographs by a member of the Swiss delegation

- ↑ Soldansätze

- ↑ Finanzielle Entschädigung

- ↑ Imogen Foulkes. Swiss still braced for nuclear war. BBC News, 10 February 2007.

- ↑ http://www.vtg.admin.ch/internet/vtg/de/home/schweizerarmee/organisation.parsys.0024.downloadList.95671.DownloadFile.tmp/95598dcenterfoldintra208web.pdf

- ↑ http://www.vtg.admin.ch/internet/vtg/de/home/schweizerarmee/organisation.parsys.0024.downloadList.95671.DownloadFile.tmp/95598dcenterfoldintra208web.pdf

External links

- Federal Department of Defence, Civil Protection and Sports — Official website

- Group for a Switzerland without an Army

- Swiss Army bike

- Swiss camouflage patterns

- Articles, books and media by Stephen P. Halbrook

- The Swiss Report: A special study for Western Goals Foundation a private intelligence dissemination network active on the right-wing in the United States.

- (German) Living history group representing the federal army of 1861

|

|||||||||||