Factorial

|

|

|---|---|

| 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 6 |

| 4 | 24 |

| 5 | 120 |

| 6 | 720 |

| 7 | 5,040 |

| 8 | 40,320 |

| 9 | 362,880 |

| 10 | 3,628,800 |

| 11 | 39,916,800 |

| 12 | 479,001,600 |

| 13 | 6,227,020,800 |

| 14 | 87,178,291,200 |

| 15 | 1,307,674,368,000 |

| 20 | 2,432,902,008,176,640,000 |

| 25 | 15,511,210,043,330,985,984,000,000 |

| 50 | 3.04140932... × 1064 |

| 70 | 1.19785717... × 10100 |

| 450 | 1.73336873... × 101,000 |

| 3,249 | 6.41233768... × 1010,000 |

| 25,206 | 1.205703438... × 10100,000 |

| 47,176 | 8.4485731495... × 10200,001 |

| 100,000 | 2.8242294079... × 10456,573 |

| 1,000,000 | 8.2639316883... × 105,565,708 |

| 9.99... × 10304 | 1 × 103.045657055180967... × 10307 |

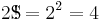

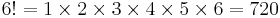

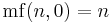

In mathematics, the factorial of a non-negative integer n, denoted by n!, is the product of all positive integers less than or equal to n. For example,

- and

The notation n! was introduced by Christian Kramp in 1808.

Contents |

Definition

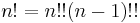

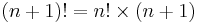

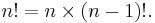

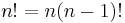

The factorial function is formally defined by

The above definition incorporates the instance

as an instance of the fact that the product of no numbers at all is 1. This fact for factorials is useful, because

- the recursive relation

works for

works for  ;

; - it allows simple construction of expressions for infinite polynomials, e.g.

;

; - this definition makes many identities in combinatorics valid for zero sizes.

- In particular, the number of combinations or permutations of an empty set is, simply, 1.

Applications

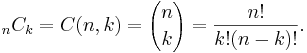

- Factorials are used in combinatorics. For example, there are

different ways of arranging n distinct objects in a sequence. (The arrangements are called permutations.) And the number of ways one can choose k objects from among a given set of n objects (the number of combinations), is given by the so-called binomial coefficient

different ways of arranging n distinct objects in a sequence. (The arrangements are called permutations.) And the number of ways one can choose k objects from among a given set of n objects (the number of combinations), is given by the so-called binomial coefficient

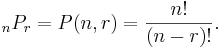

- In permutations, if

objects can be chosen from a total of n objects and arranged in different ways, where r ≤ n, then the total number of distinct permutations is given by:

objects can be chosen from a total of n objects and arranged in different ways, where r ≤ n, then the total number of distinct permutations is given by:

- Factorials also turn up in calculus. For example, Taylor's theorem expresses a function f(x) as a power series in x, basically because the nth derivative of xn is n!.

- Factorials are also used extensively in probability theory.

- Factorials are often used as a simple example, along with Fibonacci numbers, when teaching recursion in computer science because they satisfy the following recursive relationship (if n ≥ 1):

Number theory

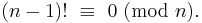

Factorials have many applications in number theory. In particular, n! is necessarily divisible by all prime numbers up to and including n. As a consequence, n > 5 is a composite number if and only if

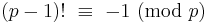

A stronger result is Wilson's theorem, which states that

if and only if p is prime.

Adrien-Marie Legendre found that the multiplicity of the prime p occurring in the prime factorization of n! can be expressed exactly as

This fact is based on counting the number of factors  of the integers from

of the integers from  to

to  . The number of multiples of

. The number of multiples of  in the numbers

in the numbers  to

to  are given by

are given by  ; however, this formula counts those numbers with two factors of

; however, this formula counts those numbers with two factors of  only once. Hence another

only once. Hence another  factors of

factors of  must be counted too. Similarly for three, four, five factors, to infinity. The sum is finite since

must be counted too. Similarly for three, four, five factors, to infinity. The sum is finite since  is less than or equal to

is less than or equal to  for only finitely many values of

for only finitely many values of  , and the floor function results in 0 when applied to

, and the floor function results in 0 when applied to

The only factorial that is also a prime number is 2, but there are many primes of the form  , called factorial primes.

, called factorial primes.

All factorials greater than 0! and 1! are even, as they are all multiples of 2.

Rate of growth

As n grows, the factorial n! becomes larger than all polynomials and exponential functions (but slower than double exponential functions) in n.

When n is large, n! can be estimated quite accurately using Stirling's approximation:

A weak version that can easily be proved with mathematical induction is

The logarithm of the factorial can be used to calculate the number of digits in a given base the factorial of a given number will take. It satisfies the identity:

Note that this function, if graphed, looks approximately linear; but the factor  , and thereby the slope of the graph, does grow arbitrarily large, although quite slowly. The graph of

, and thereby the slope of the graph, does grow arbitrarily large, although quite slowly. The graph of  for

for  between 0 and 20,000 is shown in the figure on the right.

between 0 and 20,000 is shown in the figure on the right.

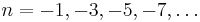

A simple approximation for log n! based on Stirling's approximation is

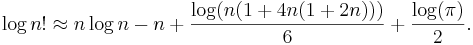

A much better approximation for log n! was given by Srinivasa Ramanujan:

One can see from this that log n! is Ο(n log n). This result plays a key role in the analysis of the computational complexity of sorting algorithms (see comparison sort).

Computation

The value of  can be calculated by repeated multiplication if

can be calculated by repeated multiplication if  is not too large. The largest factorial that most calculators can handle is 69!, because 70! > 10100 (except for most HP calculators which can handle 253! as their exponent can be up to 499). The calculator seen in Mac OS X, Microsoft Excel and Google Calculator can handle factorials up to 170!, which is the largest factorial less than 21024 (10400 in hexadecimal) and corresponds to a 1024 bit integer. The values 12! and 20! are the largest factorials that can be stored in, respectively, the 32 bit and 64 bit integers commonly used in personal computers. In practice, most software applications will compute these small factorials by direct multiplication or table lookup. Larger values are often approximated in terms of floating-point estimates of the Gamma function, usually with Stirling's formula.

is not too large. The largest factorial that most calculators can handle is 69!, because 70! > 10100 (except for most HP calculators which can handle 253! as their exponent can be up to 499). The calculator seen in Mac OS X, Microsoft Excel and Google Calculator can handle factorials up to 170!, which is the largest factorial less than 21024 (10400 in hexadecimal) and corresponds to a 1024 bit integer. The values 12! and 20! are the largest factorials that can be stored in, respectively, the 32 bit and 64 bit integers commonly used in personal computers. In practice, most software applications will compute these small factorials by direct multiplication or table lookup. Larger values are often approximated in terms of floating-point estimates of the Gamma function, usually with Stirling's formula.

For number theoretic and combinatorial computations, very large exact factorials are often needed. Bignum factorials can be computed by direct multiplication, but multiplying the sequence 1 × 2 × ... × n from the bottom up (or top-down) is inefficient; it is better to recursively split the sequence so that the size of each subproduct is minimized.

The asymptotically-best efficiency is obtained by computing n! from its prime factorization. As documented by Peter Borwein, prime factorization allows  to be computed in time O(n(log n log log n)2), provided that a fast multiplication algorithm is used (for example, the Schönhage-Strassen algorithm).[1] Peter Luschny presents source code and benchmarks for several efficient factorial algorithms, with or without the use of a prime sieve.[2]

to be computed in time O(n(log n log log n)2), provided that a fast multiplication algorithm is used (for example, the Schönhage-Strassen algorithm).[1] Peter Luschny presents source code and benchmarks for several efficient factorial algorithms, with or without the use of a prime sieve.[2]

Extension of factorial to non-integer values of argument

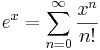

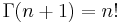

The gamma function

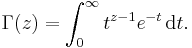

The factorial function can also be defined for non-integer values, but this requires more advanced tools from mathematical analysis. The function that "fills in" the values of the factorial between the integers is called the Gamma function, denoted  for integers z no less than 1, defined by

for integers z no less than 1, defined by

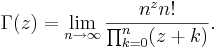

Euler's original formula for the Gamma function was

The Gamma function is related to factorials in that it satisfies a similar recursive relationship:

Together with  this yields the equation for any nonnegative integer

this yields the equation for any nonnegative integer  :

:

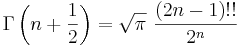

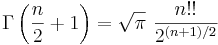

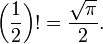

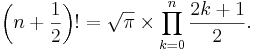

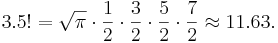

Based on the Gamma function's value for 1/2, the specific example of half-integer factorials is resolved to

For example

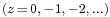

The Gamma function is in fact defined for all complex numbers  except for the nonpositive integers

except for the nonpositive integers  . It is often thought of as a generalization of the factorial function to the complex domain, which is justified for the following reasons:

. It is often thought of as a generalization of the factorial function to the complex domain, which is justified for the following reasons:

- Shared meaning. The canonical definition of the factorial function shares the same recursive relationship with the Gamma function.

- Context. The Gamma function is generally used in a context similar to that of the factorials (but, of course, where a more general domain is of interest).

- Uniqueness (Bohr–Mollerup theorem). The Gamma function is the only function which satisfies the aforementioned recursive relationship for the domain of complex numbers, is meromorphic, and is log-convex on the positive real axis. That is, it is the only smooth, log-convex function that could be a generalization of the factorial function to all complex numbers.

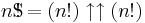

Euler also developed a convergent product approximation for the non-integer factorials, which can be seen to be equivalent to the formula for the Gamma function above:

It can also be written as below:

The product converges quickly for small values of n.

Applications of the gamma function

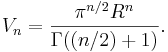

- The volume of an n-dimensional hypersphere is

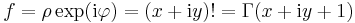

Factorial at the complex plane

Representation through the Gamma-function allows evaluation of factorial of complex argument. Equilines of amplitude and phase of factorial are shown in figure. Let  . Several levels of constant modulus (amplitude)

. Several levels of constant modulus (amplitude)  and constant phase

and constant phase  are shown. The grid covers range

are shown. The grid covers range  ,

,  with unit step. The scratched line shows the level

with unit step. The scratched line shows the level  .

.

Thin lines show internediate levels of constant modulus and constant phase. At poles  , phase and amplitude are not defined. Equilines are dense in vicinity of singularities along negative integer values of the argument.

, phase and amplitude are not defined. Equilines are dense in vicinity of singularities along negative integer values of the argument.

Factorial-like products

There are several other integer sequences similar to the factorial that are used in mathematics:

Primorial

The primorial (sequence A002110 in OEIS) is similar to the factorial, but with the product taken only over the prime numbers.

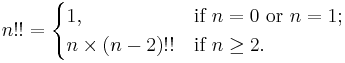

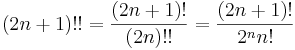

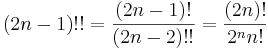

Double factorial

denotes the double factorial of

denotes the double factorial of  and is defined recursively by

and is defined recursively by

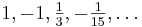

For example, 8!! = 2 · 4 · 6 · 8 = 384 and 9!! = 1 · 3 · 5 · 7 · 9 = 945. The sequence of double factorials (sequence A006882 in OEIS) for  starts as

starts as

- 1, 1, 2, 3, 8, 15, 48, 105, 384, 945, 3840, ...

The above definition can be used to define double factorials of negative numbers:

The sequence of double factorials for  starts as

starts as

while the double factorial of negative even integers is undefined.

Some identities involving double factorials are:

where  is the Gamma function. The last equation above can be used to define the double factorial as a function of any complex number

is the Gamma function. The last equation above can be used to define the double factorial as a function of any complex number  , just as the Gamma function generalizes the factorial function. One should be careful not to interpret

, just as the Gamma function generalizes the factorial function. One should be careful not to interpret  as the factorial of

as the factorial of  , which would be written

, which would be written  and is a much larger number (for

and is a much larger number (for  ).

).

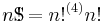

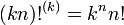

Multifactorials

A common related notation is to use multiple exclamation points to denote a multifactorial, the product of integers in steps of two ( ), three (

), three ( ), or more. The double factorial is the most commonly used variant, but one can similarly define the triple factorial (

), or more. The double factorial is the most commonly used variant, but one can similarly define the triple factorial ( ) and so on. In general, the kth factorial, denoted by

) and so on. In general, the kth factorial, denoted by  , is defined recursively as

, is defined recursively as

Some mathematicians have suggested an alternative notation of  for the double factorial and similarly

for the double factorial and similarly  for other multifactorials, but this has not come into general use.

for other multifactorials, but this has not come into general use.

In the same way that  is not defined for integers, and

is not defined for integers, and  is not defined for even integers,

is not defined for even integers,  is not defined for

is not defined for  .

.

Also,

Quadruple factorial

The so-called quadruple factorial, however, is not a multifactorial; it is a much larger number given by  .

.

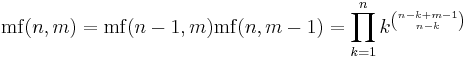

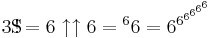

Superfactorials

Neil Sloane and Simon Plouffe defined the superfactorial in 1995 as the product of the first  factorials. So the superfactorial of 4 is

factorials. So the superfactorial of 4 is

In general

The sequence of superfactorials starts (from  ) as

) as

This idea was extended in 2000 by Henry Bottomley to the superduperfactorial as the product of the first  superfactorials, starting (from

superfactorials, starting (from  ) as

) as

and thus recursively to any multiple-level factorial where the mth-level factorial of  is the product of the first

is the product of the first

th-level factorials, i.e.

th-level factorials, i.e.

where  for

for  and

and  .

.

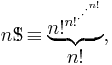

(alternative definition)

Clifford Pickover in his 1995 book Keys to Infinity defined the superfactorial of  as

as

or as,

where the (4) notation denotes the hyper4 operator, or using Knuth's up-arrow notation,

This sequence of superfactorials starts:

Here, as is usual for compound exponentiation, the grouping is understood to be from right to left:

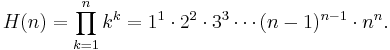

Hyperfactorials

Occasionally the hyperfactorial of  is considered. It is written as

is considered. It is written as  and defined by

and defined by

For n = 1, 2, 3, 4, ... the values H(n) are 1, 4, 108, 27648,... (sequence A002109 in OEIS).

The hyperfactorial function is similar to the factorial, but produces larger numbers. The rate of growth of this function, however, is not much larger than a regular factorial. However, H(14) = 1.85...×1099 is already almost equal to a googol, and H(15) = 8.09...×10116 is almost of the same magnitude as the Shannon number, the theoretical number of possible chess games.

The hyperfactorial function can be generalized to complex numbers in a similar way as the factorial function. The resulting function is called the K-function.

See also

- Alternating factorial

- Digamma function

- Exponential factorial

- Factoradic

- Factorial prime

- Factorion

- Stirling's approximation

- Trailing zeros of factorial

- Triangular number, the additive analogue of factorial

References

- ↑ Peter Borwein. "On the Complexity of Calculating Factorials". Journal of Algorithms 6, 376-380 (1985)

- ↑ Peter Luschny, The Homepage of Factorial Algorithms.

External links

- Approximation formulas

- All about factorial notation n!

- The Dictionary of Large Numbers

- Eric W. Weisstein, Factorial at MathWorld.

- "Factorial Factoids" by Paul Niquette

- Factorial at PlanetMath.

- Factorial calculators and algorithms

- Factorial Calculator: instantly computes factorials up to 71,352!

- "Factorial" by Ed Pegg, Jr. and Rob Morris, Wolfram Demonstrations Project, 2007.

- Fast Factorial Functions (with source code in Java and C#)

![n! \approx \left[ \left(\frac{2}{1}\right)^n\frac{1}{n+1}\right]\left[ \left(\frac{3}{2}\right)^n\frac{2}{n+2}\right]\left[ \left(\frac{4}{3}\right)^n\frac{3}{n+3}\right]\dots](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/9a85f023a0e86c57ce4ffe3c89811b40.png)