Extermination camp

| The Holocaust |

|---|

| Early elements |

| Racial policy · Nazi eugenics · Nuremberg Laws · Forced euthanasia · Concentration camps (list) |

| Jews |

| Jews in Nazi Germany (1933–1939) |

|

Pogroms: Kristallnacht · Bucharest · Dorohoi · Iaşi · Kaunas · Jedwabne · Lviv |

|

Ghettos: Łachwa · Łódź · Lwów · Kraków · Budapest · Theresienstadt · Kovno · Vilna · Warsaw |

|

Einsatzgruppen: Babi Yar · Rumbula · Ponary · Odessa · Erntefest · Ninth Fort · |

|

Final Solution: Wannsee · Operation Reinhard · Holocaust trains |

|

Concentration camps: Resistance: Jewish partisans · Ghetto uprisings (Warsaw) |

|

End of World War II: Death marches · Berihah · Displaced persons |

| Other victims |

|

Roma · Homosexuals · Disabled individuals · Slavs in Eastern Europe · Poles · Soviet POWs · Jehovah's Witnesses · Serbs |

| Responsible parties |

|

Nazi Germany: Adolf Hitler · Heinrich Himmler · Ernst Kaltenbrunner · Reinhard Heydrich · Adolf Eichmann · Schutzstaffel · Gestapo · Sturmabteilung · Nazi Party · Rudolf Höss Collaborators Aftermath: Nuremberg Trials · Denazification · Reparations Agreement |

| Lists |

| Survivors · Victims · Rescuers |

| Resources |

| The Destruction of the European Jews Functionalism versus intentionalism |

Extermination camps were two types of facilities that Nazi Germany built during World War II for the systematic killing of millions of people in what has become known as the Holocaust.[1] During World War II, under the orders of Heinrich Himmler, extermination camps were built during a later phase of the program of annihilation. Victims’ corpses were usually cremated or buried in mass graves. The groups the Nazis sought to exterminate in these camps were primarily the Jews of Europe, Eastern Europeans, as well as Roma (Gypsies). The majority of prisoners brought to extermination camps were not expected to survive more than a few hours beyond arrival.[2]

Contents |

Terminology

Extermination camp (German: Vernichtungslager) and death camp (Todeslager) are usually interchangeable and specifically refer to camps whose primary function is or was genocide.

In a generic sense, a death camp was a concentration camp that was established for the purpose of killing prisoners delivered there. All ages of people were killed at these camps. They were not intended as sites for punishing criminal actions; rather, they were intended to facilitate genocide. Historically, the most infamous death camps were the extermination camps built by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland during World War II.[3]

Nazi-German extermination camps are different than concentration camps such as Dachau and Belsen, which were mostly intended as places of incarceration and forced labor for a variety of “enemies of the state”—the Nazi label for people they deemed undesirable. In the early years of the Holocaust, the Jews were primarily sent to concentration camps, but from 1942 onward they were mostly deported to the extermination camps.

Extermination camps should also be distinguished from forced labor camps (Arbeitslager), which were set up in all German-occupied countries to exploit the labor of prisoners of various kinds, including prisoners of war. Many Jews were worked to death in these camps, but eventually the Jewish labor force, no matter how useful to the German war effort, was destined for extermination. In most Nazi camps (with the exception of POW camps for the non-Soviet soldiers and certain labor camps), there were usually very high death rates as a result of executions, starvation, disease, exhaustion, and extreme brutality; nevertheless, only the extermination camps were intended specifically for mass killing.

The distinction between extermination camps and concentration camps was recognized by Germans themselves (although not expressed in the official nomenclature of the camps.). As early as September 1942, an SS doctor witnessed a gassing and wrote in his diary: “They don't call Auschwitz the camp of annihilation (das Lager der Vernichtung) for nothing!”[4] When one of Adolf Eichmann’s deputies, Dieter Wisliceny, was interrogated at Nuremberg, he was asked for the names of extermination camps; his answer referred to Auschwitz and Majdanek as such. When asked “How do you classify the camps Mauthausen, Dachau and Buchenwald?” he replied, "They were normal concentration camps from the point of view of the department of Eichmann.”[5]

The camps

Most accounts of the Holocaust recognize six Nazi extermination camps in occupied Poland[6]:

- Auschwitz II (Auschwitz-Birkenau)

- Chełmno

- Bełżec

- Majdanek

- Sobibór

- Treblinka

Of these, Auschwitz II and Chełmno were located within areas of western Poland annexed by Germany; the other four were located in the General Government area.

Other recognized death camps outside of the main six include the little known Maly Trostenets, which was located in present day Belarus, near or in the Lokot Republic. Similar camps existed in Warsaw and Janowska. The Jasenovac concentration camp was the only central extermination camp outside of Poland, and the only one not operated by Nazis.[7][8] Run by the Ustaše forces of the Independent State of Croatia, the majority of victims at this camp were Serbs, though tens of thousands of Roma and Jews were murdered there as well.

The euphemism “Final Solution of the Jewish Question” (Endlösung der Judenfrage) was used by the Nazis to describe the systematic killing of Europe’s Jews. The decision to exterminate the Jews was presumably taken by the Nazi leadership during the first half of 1941, but no record of this decision was found. The first step of the "final solution" was made by the Einsatzgruppen that followed the Wehrmacht in Operation Barbarosa (the invasion to USSR from June 1941). However, the method of shooting the Jews in pits was found to be not efficient enough, so in late 1941 the Nazis decided to establish purpose-built camps for systematic murder in gas chambers. The details of the operation were discussed at Wannsee Conference in January 1942 and carried out under the administrative control of Adolf Eichmann. Treblinka, Bełżec, and Sobibór were constructed during Operation Reinhard, the codename for the extermination of Poland’s Jews.

While Auschwitz II was part of a labor camp complex, and Majdanek also had a labor camp, the Operation Reinhard camps and Chełmno were pure extermination camps—in other words, they were built solely and specifically to kill vast numbers of people, primarily Jews, within hours of arrival.[9] The only prisoners sent to these camps not immediately killed were those needed as slave labor directly connected with the extermination process (for example, to remove corpses from the gas chambers. These camps were small in size—only several hundred meters on each side—as only minimal housing and support facilities were required. Arriving persons were told that they were merely at a transit stop for relocation further east or at a work camp.

Non-Jews were also killed in these camps, including many gentile Poles and Soviet prisoners of war.[10]

Victim numbers

The number of people killed at the death camps has been estimated as follows:

- Auschwitz-Birkenau: about 1,100,000[11]

- Treblinka: at least 700,000[12]

- Bełżec: about 434,500[13]

- Sobibór: about 167,000[14]

- Chełmno: about 152,000[15]

- Majdanek: 78,000[16]

These numbers total just under 2,700,000 people.

Among the lesser known death camps, at least 80,000 were killed at Jasenovac, with other estimates ranging from 100-500,000. At Maly Trostenets at least 65,000 people were murdered.[17]

Polish reactions to alleged complicity

The Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, numerous Polonia organizations, as well as all Polish governments since 1989, have attributed to ignorance or malice the act of calling Nazi extermination camps in occupied Poland “Polish death camps,” and they monitor and discourage the use of this expression in favor of “(Nazi) death camps in (Nazi-)occupied Poland”[18]:

Poland had been conquered by Nazi Germany during the 1939 Invasion of Poland (1939), and its government went into exile in London; no Polish puppet state collaborated with Nazi Germany during World War II; and the decision to place extermination camps in Poland was a German one. The reasons for locating the camps in occupied Poland were simple:

- The Nazis wanted to remove all the Jews from the Greater Germany before they agreed on that Final Solution would mean extermination of all Jews (and every Jew on the planet Earth), by 1941. The Western Europe was considered "Aryan," and the Nazis did not want to pollute it with the massive numbers of Jews. Poland was ideal; it was occupied by half--human Slavs.(Based on a book: The Nazi Doctors). Moreover, the greatest complex of the death camps, Auschwitz Birkenau, was located in the eastern most Nazi Greater Germany, and, from the Nazi perspective, not in Poland.

- Poland was home to the largest Jewish population in Europe[19]

- The entire railway network in Eastern Europe was overwhelmed by the Nazi war effort; it was logistically impossible to organize on the back of the Eastern Front, the largest military operation the world has ever seen, tens of thousands of trains to transport the Jewish victims over longer distances.[20]

- The extermination camps could be kept in greater secrecy from German citizens.[21]

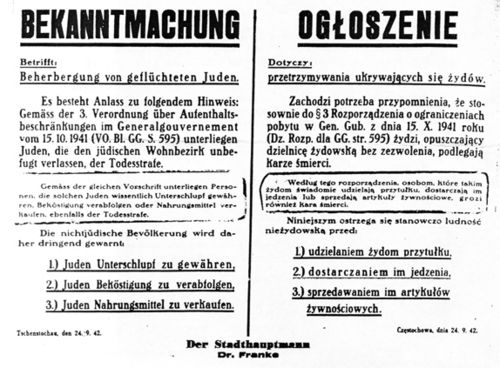

- Contrary to popular belief, the level of antisemitism in pre-war Poland had no influence on the German decision.[18] Any kind of assistance to hiding Jews incurred the death penalty. All household members were punished by death if a hidden Jew was found in their house. This was the most severe legislation in occupied Europe. Nonetheless, Poland has the highest number of Righteous among the Nations titles granted by the Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum for non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to save Jews from death at the hands of the Nazis.[22][23]

Szmalcowniks, citizens of pre-war Poland who blackmailed Jews or otherwise helped the Nazis exterminate the Jews, were treated as collaborators by the Polish Home Army and other Polish resistance movements and later punished with the death sentence.[24][25]

Operation of the camps

The method of killing at these camps was typically poison gas obtained from the German chemical company IG Farben,[26] usually in gas chambers, although many prisoners died in mass shootings, by starvation or by torture. Rudolf Höss (German spelling: Höß; not to be confused with Rudolf Hess), the commandant of Auschwitz, wrote after the war that many of the Einsatzkommandos involved in the mass shootings went mad or committed suicide, “unable to endure wading through blood any longer.”[27] The bodies of those killed were destroyed in crematoria (except at Sobibór, Treblinka and Belzec and Chelmno, where they were cremated on outdoor pyres), and the ashes buried or scattered. At Auschwitz-Birkenau, the number of corpses defied burial or burning on pyres: the only way to dispose of them was in purpose-designed furnaces built on contract by Topf und Söhne, which ran day and night.[28] In terms of operation, extermination camps divide into three groups:

- "Aktion Reinhardt" extermination camps: These are three camps established by the Nazis is the "Reinhardt Aktion": Treblinka, Sobbibor, Belzec. These camps were extermination camps, but not concentration or labor camps: inmates were brought in and, without any selection, taken to immediate extermination. These camps initiatly utilized carbon monoxide gas in gas-chambers and the bodies, which were at first buried, were burnt in pyres. In later stages, crematories were built in Treblinka and Belzec, and Zyklon-B was also put into use in Belzec. The victims were almost exclusivly of Jewish origin, save deportations of gypsies to Treblinka and Sobibor. These camps were small and were closed, in large, by late 1943.[29]

- Concentration and extermination camps: Camps that were also concentration camps, where selections took part and a minority of inmates, who were also labor-capable, were kept alive and accomodated as camp inmates. These camps underwent the upgrade of using crematories and Zyklon-B earlier, and usually remained operative untill the end of the war. These included Auschwitz, Majdanek and Jasenovac. [30]

- Minor extermination camps: location not recognised as extermination camps untill lately. These sites included smaller camps, used as detention centers and transit camps, temporarily used as extermination camps later in the war, by using portable gas-chambers or gas-vans. Chelmno, or Kulmhof, is basically such a camp, yet it is listed as a central extermination camp[31]. Others include Sajmiste, Maly-Trostenets, Janowska and Gornija Rijeka.

The camps differed slightly in operation, but all were designed to kill as efficiently as possible. For example Kurt Gerstein, an Obersturmführer in the SS medical service, testified to a Swedish diplomat during the war about what he had seen at the camps. He describes how he arrived at Belzec on August 19, 1942, (the camp's gas chambers used carbon monoxide from a gasoline engine) where he was proudly shown the unloading of 45 train cars stuffed with 6,700 Jews, many of whom were already dead, but the rest were marched naked to the gas chambers, where, he said:

Unterscharführer Hackenholt was making great efforts to get the engine running. But it doesn’t go. Captain Wirth comes up. I can see he is afraid because I am present at a disaster. Yes, I see it all and I wait. My stopwatch showed it all, 50 minutes, 70 minutes, and the diesel did not start. The people wait inside the gas chambers. In vain. They can be heard weeping, “like in the synagogue,” says Professor Pfannenstiel, his eyes glued to a window in the wooden door. Furious, Captain Wirth lashes the Ukrainian assisting Hackenholt twelve, thirteen times, in the face. After 2 hours and 49 minutes—the stopwatch recorded it all—the diesel started. Up to that moment, the people shut up in those four crowded chambers were still alive, four times 750 persons in four times 45 cubic meters. Another 25 minutes elapsed. Many were already dead, that could be seen through the small window because an electric lamp inside lit up the chamber for a few moments. After 28 minutes, only a few were still alive. Finally, after 32 minutes, all were dead… Dentists hammered out gold teeth, bridges and crowns. In the midst of them stood Captain Wirth. He was in his element, and showing me a large can full of teeth, he said: “See for yourself the weight of that gold! It’s only from yesterday and the day before. You can’t imagine what we find every day—dollars, diamonds, gold. You’ll see for yourself!”[32]

According to Höss, the first time Zyklon B was used on the Jews, many suspected they would be killed, despite being led to believe that they were only being deloused. As a result, pains were taken to single out possibly “difficult individuals” in future gassings, so they could be separated and shot unobtrusively. Members of a Special Detachment (Sonderkommando)—a group of prisoners from the camp assigned to help carry out the exterminations—were also made to accompany the Jews into the gas chamber and remain with them until the doors closed. A guard from the SS also stood at the door to perpetuate the “calming effect.” To avoid giving the prisoners time to think about their fate, they were urged to undress as speedily as possible, with the Special Detachment helping those who might slow down the process.[33]

The Special Detachment reassured the Jews being gassed by talking of life in the camp, and tried to persuade them that everything would be all right. Many Jewish women hid their infants beneath their clothes once they had undressed, because they feared the disinfectant would harm them. Höss wrote that the “men of the Special Detachment were particularly on the look-out for this,” and would encourage the womenfolk to bring their children along. The Special Detachment men were also responsible for comforting older children that might cry “because of the strangeness of being undressed in this fashion.”[34]

These measures did not deceive all, however. Höss reported of several Jews “who either guessed or knew what awaited them nevertheless” but still “found the courage to joke with the children to encourage them, despite the mortal terror visible in their own eyes.” Some women would suddenly “give the most terrible shrieks while undressing, or tear their hair, or scream like maniacs.” These were immediately led away by the Special Detachment men to be shot.[35] Some others instead “revealed the addresses of those members of their race still in hiding” before being led into the gas chamber.[36]

Once the door was sealed with the victims inside, powdered Zyklon B would be shaken down through special holes in the roof of the chamber. The camp commandant was required to witness every gassing carried out through a peephole, and supervise both the preparations and the aftermath. Höss reported that the gassed corpses “showed no signs of convulsion”; the doctors at Auschwitz attributed this to the “paralyzing effect on the lungs” that Zyklon B had, which ensured death came on before convulsions could begin.[37]

After the gassings had been carried out, the Special Detachment men would remove the bodies, extract the gold teeth and shave the hair of the corpses before bringing them to the crematoria or the pits. In either case, the bodies would be cremated, with the men of the Special Detachment responsible for stoking the fires, draining off the surplus fat, and turning over the “mountain of burning corpses” so that the flames would constantly be fanned. Höss found the attitude and dedication of the Special Detachment amazing. Despite them being “well aware that … they, too, would meet exactly the same fate,” they managed to carry out their duties “in such a matter-of-course manner that they might themselves have been the exterminators.” According to Höss, many of the Special Detachment men ate and smoked while they worked, “even when engaged on the grisly job of burning corpses.” Occasionally, they would come across the body of a close relative, but although they “were obviously affected by this, … it never led to any incident.” Höss cited the case of a man who, while carrying bodies from the gas chamber to the fire pit, found the corpse of his wife, but behaved “as though nothing had happened.”[38]

Some high-ranking leaders from the Nazi Party and the SS were sent to Auschwitz on occasion to witness the gassings. Höss wrote that although “all were deeply impressed by what they saw,” some “who had previously spoken most loudly about the necessity for this extermination fell silent once they had actually seen the ‘final solution of the Jewish problem’.” Höss was repeatedly asked how he could stomach the exterminations. He justified them by explaining “the iron determination with which we must carry out Hitler’s orders,” but found that even “[Adolf] Eichmann, who [was] certainly tough enough, had no wish to change places with me.”[39]

Post war

As the Soviet Red Army advanced into eastern Poland in 1944, the eastern most camps (excluding Auschwitz which was near Upper Silesia) were partly or completely dismantled by the Nazis to conceal the crimes which had taken place there. Because most of the camps in the very east of the country like Belzec and Sobibor were erected from natural materials locally available, like lumber, their physical remnants succumbed to the elements quicker. The postwar Polish communist government did create monuments of various kinds at the sites of the former camps, but they usually did not mention the ethnic, religious or national origin of the inmate population. This was done to create the perception of as large a homogeneous group of victims of the Nazis so that it could be used for propaganda purposes by the communist authorities in their agenda of supporting the historical communist effort in the conquest over 'German Fascism'. The hope was of the indoctrination of this theme by the citizens of Poland, the other communist block countries and the West.

After the fall of communism in 1989, the camp sites became more accessible to Western visitors to Poland and have become centers of tourism, particularly the most-infamous site at the Former Nazi-German Concentration Camp at Auschwitz near the town of Oświęcim. There had been a number of disputes in the early 1990s between world Jewish organizations and some Polish Catholics, about what are appropriate symbols of martyrdom at these sites, namely the site at Auschwitz. Some Jewish groups had objected strongly to the erection of Christian memorials at a quarry adjacent to the camp. In this, the most notable case—Auschwitz cross—a cross was located near Auschwitz I, where most of the victims were executed Poles, rather than near Auschwitz II (Auschwitz=Birkenau), which was where the majority of the Jewish victims perished.

Holocaust denial

Some groups and individuals deny that the Nazis killed anyone using extermination camps, or they question the manner or extent of the Holocaust. For example, Robert Faurisson claimed in 1979 that “Hitler’s ‘gas chambers’ never existed.” He contended that the notion of the gas chambers was “essentially of Zionist origin”. Another famous denier is British historian David Irving, who was sentenced to prison in Austria for his Holocaust denials: Holocaust denial is a criminal offense in Austria.

Scholars and historians point out that Holocaust denial is contradicted by the testimonies of survivors and perpetrators, material evidence, and photographs, as well as by the Nazis’ own record-keeping. Efforts such as the Nizkor Project, the work of Deborah Lipstadt, Simon Wiesenthal and his Simon Wiesenthal Center, and more at Holocaust resources, all track and explain Holocaust denial. The work of historians such as Raul Hilberg (who published The Destruction of the European Jews), Lucy Davidowicz (The War Against the Jews), Ian Kershaw, and many others relegate Holocaust denial to a minority fringe. Antisemitic political motivation is often imputed to those who deny the Holocaust.

The current historical debates surrounding the Nazi-German concentration camps and the Holocaust involve the questions of complicity of the local populations. Although many Jews were saved by Christian neighbors, others ignored their plight or turned them in. Furthermore, it is becoming evident that many of the camps were in clear view and were tied up in local economies. For instance, goods were purchased and delivered to camps and local women provided housekeeping and company. Nazi officers patronized local taverns and even bartered with gold collected from victims.[40]

Notes

- ↑ Doris Bergen, Germany and the Camp System, part of Auschwitz: Inside the Nazi State, Community Television of Southern California, 2004-2005

- ↑ Minerbi, Alessandra (2005). A New Illustrated History of the Nazis: Rare Photographs of the Third Reich. David & Charles. pp. 168. ISBN 0715321013. http://books.google.com/books?id=TFbfiRCVLTUC&pg=PA168&lpg=PA168&dq=%22extermination+camps%22+%2Bhours&source=web&ots=LDIfGuiKoP&sig=HW2xVgYy0mfZv-7dqaHdhUBel7I&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=2&ct=result.

- ↑ Dictionary definition on laborlawtalk.com

- ↑ Diary of Johann Paul Kremer

- ↑ Overy, Richard. Interrogations, p 356–7. Penguin 2002. ISBN 0-14-028454-0

- ↑ Holocaust Timeline: The Camps

- ↑ "Encyclopedia of the holocaust"

- ↑ M.Shelach (ed.), "History of the holocaust: Yugoslavia".

- ↑ Aktion Reinhard: Belzec, Sobibor & Treblinka, Nizkor Project

- ↑ :: Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkenau w Oświęcimiu EN ::

- ↑ http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/article.php?lang=en&ModuleId=10005189: “It is estimated that the SS and police deported at a minimum 1.3 million people to Auschwitz complex between 1940 and 1945. Of these, the camp authorities murdered 1.1 million.” (Number includes victims killed in other Auschwitz camps as well.)

- ↑ [http://www.nizkor.org/faqs/reinhard/reinhard-faq-13.html Reinhard: Treblinka Deportations

- ↑ Between March and December 1942, the Germans deported approximately 434,500 Jews and an undetermined number of Poles and Roma(Gypsies)to Belzec, where they were killed. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/article.php?lang=en&ModuleId=10005191

- ↑ In all, the Germans and their auxiliaries killed at least 167,000 people at Sobibor. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/article.php?lang=en&ModuleId=10005192

- ↑ In all, the SS and police killed at least 152,000 people in Chelmno. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/media_cm.php?lang=en&ModuleId=10005194&MediaId=130

- ↑ A recent study radically revised downward the estimated number of deaths at Majdanek. According to a piece “Majdanek Victims Enumerated” by Pawel P. Reszka, Lublin, Gazeta Wyborcza 12 December 2005, reproduced on the site of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum, Lublin scholar Tomasz Kranz has recently established this number,and the Majdanek museum staff consider it to be authoritative. Earlier estimates were considerably higher: 360,000, in a much-cited 1948 publication by Zdzislaw Lukaszkiewicz, a judge who was a member of the Main Commission for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes in Poland, and 235,000, from a 1992 article by Dr. Czesaw Rajca, now retired from the Majdanek museum staff.

- ↑ See Maly Trostinec at the campsYad Vashem website

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 http://www1.yadvashem.org/odot_pdf/Microsoft%20Word%20-%203642.pdf

- ↑ The Jewish Virtual Library - Main

- ↑ index

- ↑ Conditions for Polish Jews During WWII

- ↑ Życie za Życie

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Righteous_Among_the_Nations

- ↑ H-Net Review: John Radzilowski on Secret City: The Hidden Jews of Warsaw, 1940-1945

- ↑ http://www.totallyjewish.com/news/special_reports/?content_id=5962

- ↑ Borkin, Joseph (1978). The Crime and Punishment of IG Farben. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-02-904630-0.

- ↑ Hoss [sic], Rudolf (2005). “I, the Commandant of Auschwitz,” in Lewis, Jon E. (ed.), True War Stories, p. 321. Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 0-7867-1533-2.

- ↑ Berenbaum, Michael; Yisrael Gutman (1998). Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp. Indiana University Press. pp. 199. ISBN 025320884X. http://books.google.com/books?id=ZrU2oS8fP3cC&pg=PA199&lpg=PA199&dq=auschwitz+furnaces+day+night&source=web&ots=KnAFUCsuv6&sig=bVDl5vVGLFVpVdK2Ax0xQj8dW7s&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=3&ct=result.

- ↑ See: M. Lifshitz, "Zionism" (משה ליפשיץ, "ציונות" )p. 304. Compare with H. Abraham, "History of Israel and the nations in the era of Holocaust and uprising (חדד אברהם, "תולדות ישראל והעמים בתקופת השואה והתקומה" )"

- ↑ Ibidem

- ↑ Ibidem, pp. 101-102

- ↑ The Nazi Sourcebook: An Anthology of Texts. Routledge. 2002. pp. 354. ISBN 0415222133.

- ↑ Höss, pp. 321–322.

- ↑ Höss, pp. 322–323.

- ↑ Höss, p. 323.

- ↑ Höss, p. 324.

- ↑ Höss, pp. 320, 328.

- ↑ Höss, pp. 325–326.

- ↑ Höss, p. 328.

- ↑ Horwitz, Gordon J. “Places Far Away, Places Very Near: Mauthausen, the camps of the Shoah, and the bystanders” in Omer Bartov, ed. The Holocaust

Further reading

- Bartov, Omer (ed.). The Holocaust, 2000.

- Gilbert, Martin. Holocaust Journey: Travelling in Search of the Past, Phoenix, 1997. An account of the sites of the extermination camps as they are today, plus historical information about them and about the fate of the Jews of Poland.

- Klee, Ernst. “‘Turning the tap on was no big deal’—The gassing doctors during the Nazi period and afterwards,” in Dauchau Review, vol. 2, 1990.

- Levi, Primo. The Drowned and the Saved, 1986.