Exponential growth

Exponential growth (including exponential decay) occurs when the growth rate of a mathematical function is proportional to the function's current value. In the case of a discrete domain of definition with equal intervals it is also called geometric growth or geometric decay (the function values form a geometric progression).

With exponential growth of a positive value its rate of increase steadily increases, or in the case of exponential decay, its rate of decrease steadily decreases.

Exponential growth is said to follow an exponential law; the simple-exponential growth model is known as the Malthusian growth model. For any exponentially growing quantity, the larger the quantity gets, the faster it grows. An alternative saying is 'The rate of growth is directly proportional to the present size'. The relationship between the size of the dependent variable and its rate of growth is governed by a strict law of the simplest kind: direct proportion. It is proved in calculus that this law requires that the quantity is given by the exponential function, if we use the correct time scale. This explains the name.

Contents |

Examples

- Biology.

- The number of microorganisms in a culture broth will grow exponentially until an essential nutrient is exhausted. Typically the first organism splits into two daughter organisms, who then each split to form four, who split to form eight, and so on.

- A virus ([for example SARS, West Nile or smallpox) typically will spread exponentially at first, if no artificial immunization is available. Each infected person can infect multiple new people.

- Human population, if the number of births and deaths per person per year were to remain at current levels (but also see logistic growth).

- Many responses of living beings to stimuli, including human perception, are logarithmic responses, which are the inverse of exponential responses; the loudness and frequency of sound are perceived logarithmically, even with very faint stimulus, within the limits of perception. This is the reason that exponentially increasing the brightness of visual stimuli is perceived by humans as a linear increase, rather than an exponential increase. This has survival value. Generally it is important for the organisms to respond to stimuli in a wide range of levels, from very low levels, to very high levels, while the accuracy of the estimation of differences at high levels of stimulus is much less important for survival.

- Physics

- Avalanche breakdown within a dielectric material. A free electron becomes sufficiently accelerated by an externally applied electrical field that it frees up additional electrons as it collides with atoms or molecules of the dielectric media. These secondary electrons also are accelerated, creating larger numbers of free electrons. The resulting exponential growth of electrons and ions may rapidly lead to complete dielectric breakdown of the material.

- Nuclear chain reaction (the concept behind nuclear weapons). Each uranium nucleus that undergoes fission produces multiple neutrons, each of which can be absorbed by adjacent uranium atoms, causing them to fission in turn. If the probability of neutron absorption exceeds the probability of neutron escape (a function of the shape and mass of the uranium), k > 0 and so the production rate of neutrons and induced uranium fissions increases exponentially, in an uncontrolled reaction.

- Multi-level marketing

- Exponential increases are promised to appear in each new level of a starting member's downline as each subsequent member recruits more people.

- Computer technology

- Processing power of computers. See also Moore's law and technological singularity (under exponential growth, there are no singularities. The singularity here is a metaphor.).

- In computational complexity theory, computer algorithms of exponential complexity require an exponentially increasing amount of resources (e.g. time, computer memory) for only a constant increase in problem size. So for an algorithm of time complexity 2^x, if a problem of size x=10 requires 10 seconds to complete, and a problem of size x=11 requires 20 seconds, then a problem of size x=12 will require 40 seconds. This kind of algorithm typically becomes unusable at very small problem sizes, often between 30 and 100 items (most computer algorithms need to be able to solve much larger problems, up to tens of thousands or even millions of items in reasonable times, something that would be physically impossible with an exponential algorithm). Also, the effects of Moore's Law do not help the situation much because doubling processor speed merely allows you to increase the problem size by a constant. E.g. if a slow processor can solve problems of size x in time t, then a processor twice as fast could only solve problems of size x+constant in the same time t. So exponentially complex algorithms are most often impractical, and the search for more efficient algorithms is one of the central goals of computer science.

- Internet traffic growth.

- Investment. Compound interest at a constant interest rate provides exponential growth of the capital. See also rule of 72

Basic formula

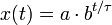

A quantity x depends exponentially on time t if

where the constant a is the initial value of x,

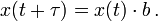

and the constant b is a positive growth factor, and τ is the time required for x to increase by a factor of b:

If τ > 0 and b > 1, then x has exponential growth. If τ < 0 and b > 1, or τ > 0 and 0 < b < 1, then x has exponential decay.

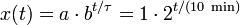

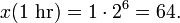

Example: If a species of bacteria doubles every ten minutes, starting out with only one bacterium, how many bacteria would be present after one hour? The question implies a = 1, b = 2 and τ = 10 min.

After one hour, or six ten-minute intervals, there would be sixty-four bacteria.

Many pairs (b, τ) of a dimensionless non-negative number b and an amount of time τ (a physical quantity which can be expressed as the product of a number of units and a unit of time) represent the same growth rate, with τ proportional to log b. For any fixed b not equal to 1 (e.g. e or 2), the growth rate is given by the non-zero time τ. For any non-zero time τ the growth rate is given by the dimensionless positive number b.

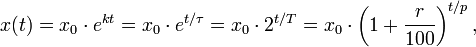

Thus the law of exponential growth can be written in different but mathematically equivalent forms, by using a different base. The most common forms are the following:

where x0 expresses the initial quantity x(0).

Parameters (negative in the case of exponential decay):

- The growth constant k is the frequency (number of times per unit time) of growing by a factor e; in finance it is also called the logarithmic return, continuously compounded return, or force of interest.

- The e-folding time

is the time it takes to grow by a factor e.

is the time it takes to grow by a factor e. - The doubling time T is the time it takes to double.

- The percent increase r (a dimensionless number) in a period p.

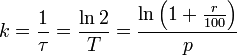

The quantities k,  , and T, and for a given p also r, have a one-to-one connection given by the following equation (which can be derived by taking the natural logarithm of the above):

, and T, and for a given p also r, have a one-to-one connection given by the following equation (which can be derived by taking the natural logarithm of the above):

where k = 0 corresponds to r = 0 and to  and T being infinite.

and T being infinite.

If p is the unit of time the quotient t/p is simply the number of units of time. Using the notation t for the (dimensionless) number of units of time rather than the time itself, t/p can be replaced by t, but for uniformity this has been avoided here. In this case the division by p in the last formula is not a numerical division either, but converts a dimensionless number to the correct quantity including unit.

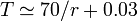

A popular approximated method for calculating the doubling time from the growth rate is the rule of 70, i.e.  (or better:

(or better:  ).

).

Differential equation

The exponential function x(t) = x0 ekt has initial value x0 and satisfies the differential equation:

Thus growth is proportial to the value. In the special case k = 0 the function is constant. If the function is constantly zero any growth rate trivially applies.

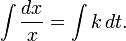

Starting from the differential equation, it is solved by the method of separation of variables. Formally multiply by dt/x, and integrate to obtain

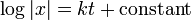

Carrying out the integrations,

So the logarithm grows linearly, and the solution is found.

See logistic function for a simple correction of this growth model where k is not constant.

Other growth rates

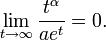

In the long run, exponential growth of any kind will overtake linear growth of any kind (the basis of the Malthusian catastrophe) as well as any polynomial growth, i.e., for all α:

There is a whole hierarchy of conceivable growth rates that are slower than exponential and faster than linear (in the long run). See Degree of a polynomial#The degree computed from the function values.

Growth rates may also be faster than exponential.

In the above differential equation, if k < 0, then the quantity experiences exponential decay.

Limitations of models

Exponential growth models of physical phenomena only apply within limited regions, as unbounded growth is not physically realistic. Although growth may initially be exponential, the modelled phenomena will eventually enter a region in which previously ignored negative feedback factors become significant (leading to a logistic growth model) or other underlying assumptions of the exponential growth model, such as continuity or instantaneous feedback, break down.

- Further information: Limits to Growth, Malthusian catastrophe

Exponential stories

The surprising characteristics of exponential growth have fascinated people through the ages.

Rice on a chessboard

A courtier presented the Persian king with a beautiful, hand-made chessboard. The king asked what he would like in return for his gift and the courtier surprised the king by asking for one grain of rice on the first square, two grains on the second, four grains on the third etc. The king readily agreed and asked for the rice to be brought. All went well at first, but the requirement for 2 n − 1 grains on the nth square demanded over a million grains on the 21st square, more than a million million (aka trillion) on the 41st and there simply was not enough rice in the whole world for the final squares. (From Meadows et al. 1972, p.29 via Porritt 2005)

For variation of this see Second Half of the Chessboard in reference to the point where an exponentially growing factor begins to have a significant economic impact on an organization's overall business strategy.

The water lily

French children are told a story in which they imagine having a pond with water lily leaves floating on the surface. The lily population doubles in size every day and if left unchecked will smother the pond in 30 days, killing all the other living things in the water. Day after day the plant seems small and so it is decided to leave it to grow until it half-covers the pond, before cutting it back. They are then asked, on what day that will occur. This is revealed to be the 29th day, and then there will be just one day to save the pond. (From Meadows et al. 1972, p.29 via Porritt 2005)

See also

- Albert Bartlett

- arthrobacter

- bacterial growth

- cell growth

- Hausdorff dimension

- information explosion

- law of accelerating returns

- logistic curve

- exponential algorithm

- asymptotic notation

- EXPSPACE

- EXPTIME

- Moore's Law

- list of exponential topics

- Menger sponge

References

Sources

- Meadows, Donella H., Dennis L. Meadows, Jørgen Randers, and William W. Behrens III. (1972) The Limits to Growth. New York: University Books. ISBN 0-87663-165-0

- Porritt, J. Capitalism as if the world matters, Earthscan 2005. ISBN 1-84407-192-8

- Thomson, David G. Blueprint to a Billion: 7 Essentials to Achieve Exponential Growth, Wiley Dec 2005, ISBN 0-471-74747-5

- Tsirel, S. V. 2004. On the Possible Reasons for the Hyperexponential Growth of the Earth Population. Mathematical Modeling of Social and Economic Dynamics / Ed. by M. G. Dmitriev and A. P. Petrov, pp. 367–9. Moscow: Russian State Social University, 2004.

External links

- Exponent calculator — One of the best ways to see how exponents work is to simply try different examples. This calculator enables you to enter an exponent and a base number and see the result.

- Exponential Growth Calculator — This calculator enables you to perform a variety of calculations relating to exponential consumption growth.

- Understanding Exponential Growth — video clip 8.5 min

- Dr. Albert Bartlett: Arithmetic, Population and Energy — sreaming video and audio 58 min