Euler's formula

- This article is about Euler's formula in complex analysis. For Euler's formula in algebraic topology and polyhedral combinatorics see Euler characteristic. See also topics named after Euler.

|

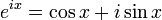

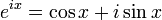

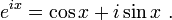

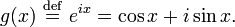

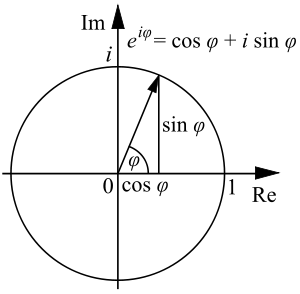

Euler's formula, named after Leonhard Euler, is a mathematical formula in complex analysis that shows a deep relationship between the trigonometric functions and the complex exponential function. Euler's formula states that, for any real number x,

where e is the base of the natural logarithm, i is the imaginary unit, and cos and sin are the trigonometric functions cosine and sine, with the argument x given in radians rather than in degrees. The formula is still valid if x is a complex number, and so some authors refer to the more general complex version as Euler's formula.[1]

Richard Feynman called Euler's formula "our jewel" and "the most remarkable formula in mathematics".[2]

Contents |

History

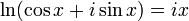

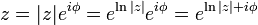

Euler's formula was proven for the first time by Roger Cotes in 1714 in the form

(where "ln" means natural logarithm, i.e. log with base e).[3]

It was Euler who published the equation in its current form in 1748, basing his proof on the infinite series of both sides being equal. Neither of these men saw the geometrical interpretation of the formula: the view of complex numbers as points in the complex plane arose only some 50 years later (see Caspar Wessel). Euler considered it natural to introduce students to complex numbers much earlier than we do today. In his elementary algebra text book, Elements of Algebra, he introduces these numbers almost at once and then uses them in a natural way throughout.

Applications in complex number theory

This formula can be interpreted as saying that the function eix traces out the unit circle in the complex number plane as x ranges through the real numbers. Here, x is the angle that a line connecting the origin with a point on the unit circle makes with the positive real axis, measured counter clockwise and in radians.

The original proof is based on the Taylor series expansions of the exponential function ez (where z is a complex number) and of sin x and cos x for real numbers x (see below). In fact, the same proof shows that Euler's formula is even valid for all complex numbers z.

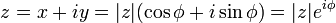

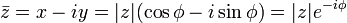

A point in the complex plane can be represented by a complex number written in cartesian coordinates. Euler's formula provides a means of conversion between cartesian coordinates and polar coordinates. The polar form reduces the number of terms from two to one, which simplifies the mathematics when used in multiplication or powers of complex numbers. Any complex number z = x + iy can be written as

where

the real part

the real part the imaginary part

the imaginary part the magnitude of z

the magnitude of z atan2(y, x)

atan2(y, x)

is the argument of z—i.e., the angle between the x axis and the vector z measured counterclockwise and in radians—which is defined up to addition of 2π.

is the argument of z—i.e., the angle between the x axis and the vector z measured counterclockwise and in radians—which is defined up to addition of 2π.

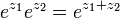

Now, taking this derived formula, we can use Euler's formula to define the logarithm of a complex number. To do this, we also use the definition of the logarithm (as the inverse operator of exponentiation) that

and that

both valid for any complex numbers a and b.

Therefore, one can write:

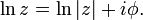

for any  . Taking the logarithm of both sides shows that:

. Taking the logarithm of both sides shows that:

and in fact this can be used as the definition for the complex logarithm. The logarithm of a complex number is thus a multi-valued function, because  is multi-valued.

is multi-valued.

Finally, the other exponential law

which can be seen to hold for all integers k, together with Euler's formula, implies several trigonometric identities as well as de Moivre's formula.

Relationship to trigonometry

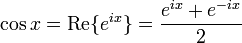

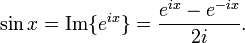

Euler's formula provides a powerful connection between analysis and trigonometry, and provides an interpretation of the sine and cosine functions as weighted sums of the exponential function:

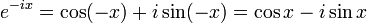

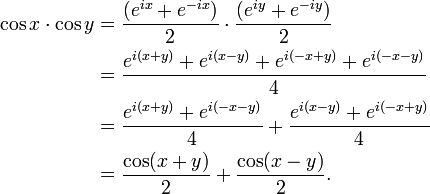

The two equations above can be derived by adding or subtracting Euler's formulas:

and solving for either cosine or sine.

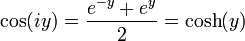

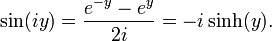

These formulas can even serve as the definition of the trigonometric functions for complex arguments x. For example, letting x = iy, we have:

Complex exponentials can simplify trigonometry, because they are easier to manipulate than their sinusoidal components. One technique is simply to convert sinusoids into equivalent expressions in terms of exponentials. After the manipulations, the simplified result is still real-valued. For example:

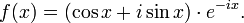

Another technique is to represent the sinusoids in terms of the real part of a more complex expression, and perform the manipulations on the complex expression. For example:

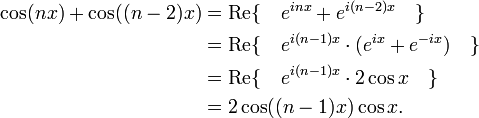

This formula is used for recursive generation of  for integer values of n and arbitrary x (in radians).

for integer values of n and arbitrary x (in radians).

Other applications

In differential equations, the function eix is often used to simplify derivations, even if the final answer is a real function involving sine and cosine. Euler's identity is an easy consequence of Euler's formula.

In electrical engineering and other fields, signals that vary periodically over time are often described as a combination of sine and cosine functions (see Fourier analysis), and these are more conveniently expressed as the real part of exponential functions with imaginary exponents, using Euler's formula. Also, phasor analysis of circuits can include Euler's formula to represent the impedance of a capacitor or an inductor.

Definitions of complex exponentiation

In general, raising e to a positive integer exponent has a simple interpretation in terms of repeated multiplication of e. Raising e to zero or a negative integer exponent can be understood as repeated division. A rational number exponent can be defined by radicals of e, and an irrational number exponent can be defined by finding rational-number exponents that are arbitrarily close to the irrational-number exponent, in a limit process. However, to define and understand a complex number exponent of e, a different type of generalization is required for the concept of exponentiation.

In fact, several definitions are possible. All of them can be proven to be well-defined and equivalent, although the proofs are not included in this article.

Taylor series definition

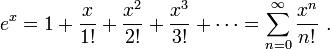

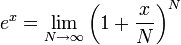

It is well-known that, for any real x, the following series is equal to ex:

(in other words, this is the Taylor series for the real exponential function, and it has an infinite radius of convergence). This invites the following definition of ez for complex z:

This can be proven to be well-defined; in particular, the series converges for any z.

Analytic continuation definition

A simple-to-state, equivalent definition is that ez, for complex z, is the analytic continuation of the function ex for real x. This can be proven to be well-defined; in particular, it yields a single-valued function on the complex plane.

Limit definition

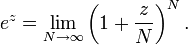

It is well-known that, for any real x, the following limit is equal to ex:

This motivates the following definition of ez for complex z:

Differential equation definition

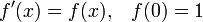

For real x, the function f(x)=ex is well-known to be the unique real function satisfying the differential equation:

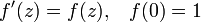

for all x. This motivates a definition of f(z)=ez for complex z as the function that satisfies the differential equation:

for all complex z, where the derivative in f'(z) is defined in the sense of a complex derivative. This can be proven to yield a unique function which is well-defined everywhere on the complex plane.

Multiplicative property definition

We would expect the function ez to have the following properties:

is continuous

is continuous

It turns out that this uniquely specifies a function on the complex plane.

Proofs

Various proofs of this formula are possible. The first proof below starts with the "Taylor series definition" of ez, while the other two use the "Differential equation definition" of ez (see above).

Using Taylor series

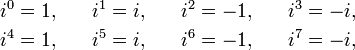

Here is a proof of Euler's formula using Taylor series expansions as well as basic facts about the powers of i:

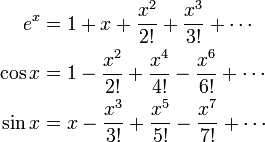

and so on. The functions ex, cos x and sin x of the (real) variable x can be expressed using their Taylor expansions around zero:

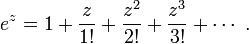

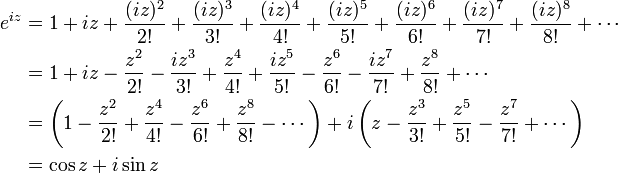

For complex z we define each of these functions by the above series, replacing the real variable x with the complex variable z. This is possible because the radius of convergence of each series is infinite. We then find that

The rearrangement of terms is justified because each series is absolutely convergent. Taking z = x to be a real number gives the original identity as Euler discovered it.

Using calculus

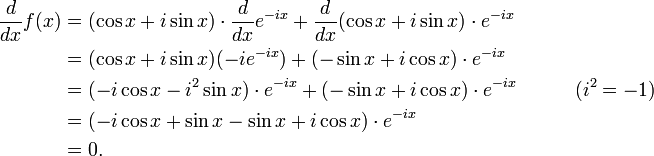

Define the (possibly complex) function ƒ(x), of real variable x, as

The derivative of ƒ(x), according to the product rule, is:

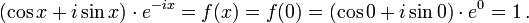

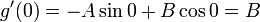

Therefore, ƒ(x) must be a constant function in x. Because ƒ(0) is known, the constant that ƒ(x) equals for all real x is also known. Thus,

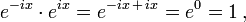

Multiplying both sides by eix and using

it follows that

Q.E.D.

Using ordinary differential equations

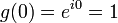

Define the function g(x) by

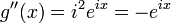

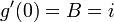

Considering that i is constant, the first and second derivatives of g(x) are

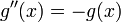

because i 2 = −1 by definition. From this the following 2nd-order linear ordinary differential equation is constructed:

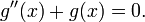

or

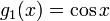

Being a 2nd-order differential equation, there are two linearly independent solutions that satisfy it:

Both cos and sin are real functions in which the 2nd derivative is identical to the negative of that function. Any linear combination of solutions to a homogeneous differential equation is also a solution. Then, in general, the solution to the differential equation is

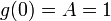

for any constants A and B. But not all values of these two constants satisfy the known initial conditions for g(x):

.

.

However these same initial conditions (applied to the general solution) are

resulting in

and, finally,

Q.E.D.

See also

- Leonhard Euler

- Euler's identity

- Complex number

- de Moivre's formula

- Exponentiation

- Exponential function

References

- ↑ Moskowitz, Martin A. (2002). A Course in Complex Analysis in One Variable. World Scientific Publishing Co.. pp. 7. ISBN 981-02-4780-X.

- ↑ Feynman, Richard P. (1977). The Feynman Lectures on Physics, vol. I. Addison-Wesley. pp. 22–10. ISBN 0-201-02010-6.

- ↑ John Stillwell (2002). Mathematics and Its History. Springer.