Ergodic theory

Ergodic theory is a branch of mathematics that studies dynamical systems with an invariant measure and related problems. Its initial development was motivated by problems of statistical physics.

A central aspect of ergodic theory is the behavior of a dynamical system when it is allowed to run for a long period of time. This is expressed through ergodic theorems which assert that, under certain conditions, the time average of a function along the trajectories exists almost everywhere and is related to the space average. Two most important examples are the ergodic theorems of Birkhoff and von Neumann. For the special class of ergodic systems, the time average is the same for almost all initial points: statistically speaking, the system that evolves for a long time "forgets" its initial state. Stronger properties, such as mixing and equidistribution have also been extensively studied. The problem of metric classification of systems is another important part of the abstract ergodic theory. An outstanding role in ergodic theory and its applications to stochastic processes is played by the various notions of entropy for dynamical systems.

Applications of ergodic theory to other parts of mathematics usually involve establishing ergodicity properties for systems of special kind. In geometry, methods of ergodic theory have been used to study the geodesic flow on Riemannian manifolds, starting with the results of Eberhard Hopf for Riemann surfaces of negative curvature. Markov chains form a common context for applications in probability theory. Ergodic theory has fruitful connections with harmonic analysis, Lie theory (representation theory, lattices in algebraic groups), and number theory (the theory of diophantine approximations, L-functions).

Contents |

Ergodic transformation

A measure-preserving transformation T on a probability space is said to be ergodic if the only measurable sets invariant under T have measure 0 or 1. An older term for this property was metrically transitive.

Let  be a measure-preserving transformation on a measure space

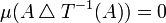

be a measure-preserving transformation on a measure space  . An element A of

. An element A of  is T-invariant if A differs from

is T-invariant if A differs from  by a set of measure zero, i.e., if

by a set of measure zero, i.e., if

where  denotes the set-theoretic symmetric difference of A and B.

denotes the set-theoretic symmetric difference of A and B.

The transformation T is said to be ergodic if for every T-invariant element A of  , either A or X\A has measure zero.

, either A or X\A has measure zero.

Ergodic transformations capture a very common phenomenon in statistical physics. For instance, if one thinks of the measure space as a model for the particles of some gas contained in a bounded recipient, with X being a finite set of positions that the particles fill at any time and  the counting measure on X, and if T(x) is the position of the particle x after one unit of time, then the assertion that T is ergodic means that any part of the gas which is not empty nor the whole recipient is mixed with its complement during one unit of time. This is of course a reasonable assumption from a physical point of view.

the counting measure on X, and if T(x) is the position of the particle x after one unit of time, then the assertion that T is ergodic means that any part of the gas which is not empty nor the whole recipient is mixed with its complement during one unit of time. This is of course a reasonable assumption from a physical point of view.

Ergodic theorem (Individual or Birkhoff)

Let  be a measure-preserving transformation on a measure space

be a measure-preserving transformation on a measure space  . One may then consider the "time average" of a well-behaved function f (more precisely, f must be L1-integrable with respect to measure

. One may then consider the "time average" of a well-behaved function f (more precisely, f must be L1-integrable with respect to measure  , i.e.

, i.e.  ). The "time average" is defined as the average (if it exists) over iterations of T starting from some initial point x.

). The "time average" is defined as the average (if it exists) over iterations of T starting from some initial point x.

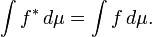

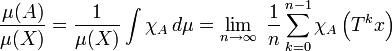

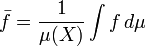

If  is finite and nonzero, we can consider the "space average" or "phase average" of f, defined as

is finite and nonzero, we can consider the "space average" or "phase average" of f, defined as

.

.

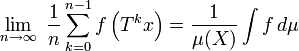

In general the time average and space average may be different. But if the transformation is ergodic, and the measure is invariant, then the time average is equal to the space average almost everywhere. This is the celebrated ergodic theorem, in an abstract form due to George David Birkhoff. (Actually, Birkhoff's paper considers not the abstract general case but only the case of dynamical systems arising from differential equations on a smooth manifold.) The equidistribution theorem is a special case of the ergodic theorem, dealing specifically with the distribution of probabilities on the unit interval.

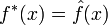

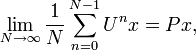

More precisely, the pointwise or strong ergodic theorem states that the time average of f converges almost everywhere and that there exists a

such that

for almost all  . Furthermore,

. Furthermore,  is T-invariant, so that

is T-invariant, so that

almost everywhere, and if  is finite, then the normalization is the same:

is finite, then the normalization is the same:

In general, if T is ergodic and if  is T-invariant,

is T-invariant,  is constant almost everywhere, and so one has that

is constant almost everywhere, and so one has that

almost everywhere. Joining the first to the last claim and assuming that  is finite and nonzero, one has that

is finite and nonzero, one has that

for almost all x, i.e., for all x except for a set of measure zero.

For an ergodic transformation, the time average equals the space average almost surely.

As an example, assume that the measure space  models the particles of a gas as above, and let f(x) denotes the velocity of the particle at position x. Then the pointwise ergodic theorems says that the average velocity of all particles at some given time is equal to the average velocity of one particle over time.

models the particles of a gas as above, and let f(x) denotes the velocity of the particle at position x. Then the pointwise ergodic theorems says that the average velocity of all particles at some given time is equal to the average velocity of one particle over time.

Mean Ergodic Theorem

Another form of the ergodic theorem, von Neumann's mean ergodic theorem, holds in Hilbert spaces.[1]

Let  be a unitary operator on a Hilbert space

be a unitary operator on a Hilbert space  . Let

. Let  be the orthogonal projection onto

be the orthogonal projection onto  .

.

Then, for any  , we have:

, we have:

where the limit is with respect to the norm on H. In other words, the sequence of averages

converges to P in the strong operator topology.

This theorem specializes to the case in which the Hilbert space H consists of L2 functions on a measure space and U is an operator of the form

where T is a measure-preserving automorphism of X, thought of in applications as representing a time-step of a discrete dynamical system.[2] The ergodic theorem then asserts that the average behavior of a function f over sufficiently large time-scales is approximated by the orthogonal component of f which is time-invariant.

In another form of the mean ergodic theorem, let Ut be a continuous one-parameter group of unitary operators on H. Then the operator

converges in the strong operator topology as T → ∞.

Sojourn time

Let  be a measure space such that

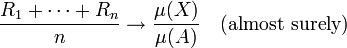

be a measure space such that  is finite and nonzero. The time spent in a measurable set A is called the sojourn time. An immediate consequence of the ergodic theorem is that, in an ergodic system, the relative measure of A is equal to the mean sojourn time:

is finite and nonzero. The time spent in a measurable set A is called the sojourn time. An immediate consequence of the ergodic theorem is that, in an ergodic system, the relative measure of A is equal to the mean sojourn time:

where  is the indicator function of A, for all x except for a set of measure zero.

is the indicator function of A, for all x except for a set of measure zero.

Let the occurrence times of a measurable set A be defined as the set k1, k2, k3, ..., of times k such that Tk(x) is in A, sorted in increasing order. The differences between consecutive occurrence times Ri = ki − ki−1 are called the recurrence times of A. Another consequence of the ergodic theorem is that the average recurrence time of A is inversely proportional to the measure of A, assuming that the initial point x is in A, so that k0 = 0.

(See almost surely.) That is, the smaller A is, the longer it takes to return to it.

Ergodic flows on manifolds

The ergodicity of the geodesic flow on compact Riemann surfaces of variable negative curvature and on compact manifolds of constant negative curvature of any dimension was proved by Eberhard Hopf in 1939, although special cases had been studied earlier: see for example, Hadamard's billiards (1898) and Artin billiard (1924). The relation between geodesic flows on Riemann surfaces and one-parameter subgroups on SL(2,R) was described in 1952 by S. V. Fomin and I. M. Gelfand. The article on Anosov flows provides an example of ergodic flows on SL(2,R) and on Riemann surfaces of negative curvature. Much of the development described there generalizes to hyperbolic manifolds, since they can be viewed as quotients of the hyperbolic space by the action of a lattice in the semisimple Lie group SO(n,1). Ergodicity of the geodesic flow on Riemannian symmetric spaces was demonstrated by F. I. Mautner in 1957. In 1967 D. V. Anosov and Ya. G. Sinai proved ergodicity of the geodesic flow on compact manifolds of variable negative sectional curvature. A simple criterion for the ergodicity of a homogeneous flow on a homogeneous space of a semisimple Lie group was given by C. C. Moore in 1966. Many of the theorems and results from this area of study are typical of rigidity theory.

In the 1930s G. A. Hedlund proved that the horocycle flow on a compact hyperbolic surface is minimal and ergodic. Unique ergodicity of the flow was established by Hillel Furstenberg in 1972. Ratner's theorems provide a major generalization of ergodicity for unipotent flows on the homogeneous spaces of the form Γ\G, where G is a Lie group and Γ is a lattice in G.

See also

- Chaos theory

- Dynamical systems theory

- Ergodic hypothesis

- Ergodic process

- Functional analysis

- Maximal ergodic theorem

- Mean sojourn time

- Poincaré recurrence theorem

- Statistical mechanics

- Markov chain

References

- ↑ I: Functional Analysis : Volume 1 by Michael Reed, Barry Simon,Academic Press; REV edition (1980)

- ↑ (Walters 1982)

Historical references

- Birkhoff, George David (1931), "Proof of the ergodic theorem", Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 17: 656-660, http://www.pnas.org/cgi/reprint/17/12/656.

- Birkhoff, George David (1942), "What is the ergodic theorem?", American Mathematical Monthly 49 (4): 222-226, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2303229.

- von Neumann, John (1932), "Proof of the Quasi-ergodic Hypothesis", Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 18: 70-82.

- von Neumann, John (1932), "Physical Applications of the Ergodic Hypothesis", Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 18: 263-266, http://www.jstor.org/stable/86260.

- Hopf, Eberhard (1939), "Statistik der geodätischen Linien in Mannigfaltigkeiten negativer Krümmung", Leipzig Ber. Verhandl. Sächs. Akad. Wiss. 91: 261-304.

- Fomin, Sergei V.; Gelfand, I. M. (1952), "Geodesic flows on manifolds of constant negative curvature", Uspehi Mat. Nauk 7 (1): 118-137.

- Mautner, F. I. (1957), "Geodesic flows on symmetric Riemann spaces", Ann. of Math. 65: 416-431.

- Moore, C. C. (1966), "Ergodicity of flows on homogeneous spaces", Amer. J. Math. 88: 154-178.

Modern references

- D.V. Anosov (2001), "Ergodic theory", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopaedia of Mathematics, Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1556080104

- This article incorporates material from ergodic theorem on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the GFDL.

- Vladimir Igorevich Arnol'd and André Avez, Ergodic Problems of Classical Mechanics. New York: W.A. Benjamin. 1968.

- Leo Breiman, Probability. Original edition published by Addison-Wesley, 1968; reprinted by Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 1992. ISBN 0-89871-296-3. (See Chapter 6.)

- Peter Walters, An introduction to ergodic theory, Springer, New York, 1982, ISBN 0-387-95152-0.

- Tim Bedford, Michael Keane and Caroline Series, eds. (1991). Ergodic theory, symbolic dynamics and hyperbolic spaces. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-853390-X. (A survey of topics in ergodic theory; with exercises.)

- Karl Petersen. Ergodic Theory (Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1990.

- Joseph M. Rosenblatt and Máté Weirdl, Pointwise ergodic theorems via harmonic analysis, (1993) appearing in Ergodic Theory and its Connections with Harmonic Analysis, Proceedings of the 1993 Alexandria Conference, (1995) Karl E. Petersen and Ibrahim A. Salama, eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, ISBN 0-521-45999-0. (An extensive survey of the ergodic properties of generalizations of the equidistribution theorem of shift maps on the unit interval. Focuses on methods developed by Bourgain.)