Geologic time scale

The geologic time scale is a chronologic schema (or idealized Model) relating stratigraphy to time that is used by geologists and other earth scientists to describe the timing and relationships between events that have occurred during the history of Earth. The table of geologic time spans presented here agrees with the dates and nomenclature proposed by the International Commission on Stratigraphy, and uses the standard color codes of the United States Geological Survey.

Evidence from radiometric dating indicates that the Earth is about 4.570 billion years old. The geological or deep time of Earth's past has been organized into various units according to events which took place in each period. Different spans of time on the time scale are usually delimited by major geological or paleontological events, such as mass extinctions. For example, the boundary between the Cretaceous period and the Paleogene period is defined by the extinction event, known as the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction event, that marked the demise of the dinosaurs and of many marine species. Older periods which predate the reliable fossil record are defined by absolute age.

Contents |

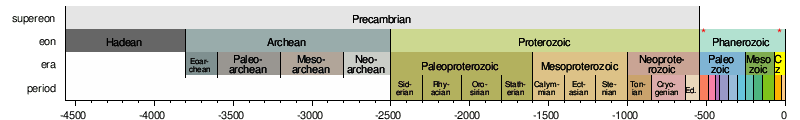

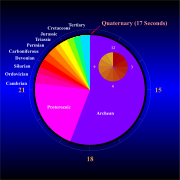

Graphical timelines

The second and third timelines are each subsections of their preceding timeline as indicated by asterisks.

The Holocene (the latest epoch) is too small to be shown clearly on this timeline.

Terminology

|

|

||

| Segments of rock (strata) in chronostratigraphy | Periods of time in geochronology | Notes |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

4 total, half a billion years or more |

|

|

|

12 total, several hundred million years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

tens of millions of years |

|

|

|

millions of years |

|

|

|

smaller than an age/stage, not used by the ICS timescale |

The largest defined unit of time is the supereon, composed of eons. Eons are divided into eras, which are in turn divided into periods, epochs and ages. The terms eonothem, erathem, system, series, and stage are used to refer to the layers of rock that correspond to these periods of geologic time.

Geologists tend to talk in terms of Upper/Late, Lower/Early and Middle parts of periods and other units , such as "Upper Jurassic", and "Middle Cambrian". Upper, Middle, and Lower are terms applied to the rocks themselves, as in "Upper Jurassic sandstone," while Late, Middle, and Early are applied to time, as in "Early Jurassic deposition" or "fossils of Early Jurassic age." The adjectives are capitalized when the subdivision is formally recognized, and lower case when not; thus "early Miocene" but "Early Jurassic." Because geologic units occurring at the same time but from different parts of the world can often look different and contain different fossils, there are many examples where the same period was historically given different names in different locales. For example, in North America the Lower Cambrian is referred to as the Waucoban series that is then subdivided into zones based on trilobites. The same timespan is split into Tommotian, Atdabanian and Botomian stages in East Asia and Siberia. A key aspect of the work of the International Commission on Stratigraphy is to reconcile this conflicting terminology and define universal horizons that can be used around the world.

History of the time scale

The first geologic time scale was proposed in 1913 by the British geologist Arthur Holmes.[2] He greatly furthered the newly created discipline of geochronology and published the world renowned book The Age of the Earth in 1913 in which he estimated the Earth's age to be at least 1.6 billion years.[3]

Aristotle realized that fossil seashells from rocks were similar to those found on the beach, indicating the fossils were once living animals. He deduced that the positions of land and sea had changed and these changes occurred over long periods of time. Leonardo da Vinci concurred with Aristotle's view that fossils were the remains of ancient life.[4]

One of the principles underlying geologic time scales was the principle of superposition of strata, first proposed in the 11th century by the Persian geologist, Avicenna (Ibn Sina). However, he rejected the explanation of fossils as organic remains.[5] While discussing the origins of mountains in The Book of Healing in 1027, he outlined the principle as follows:[6][7]

"It is also possible that the sea may have happened to flow little by little over the land consisting of both plain and mountain, and then have ebbed away from it. ... It is possible that each time the land was exposed by the ebbing of the sea a layer was left, since we see that some mountains appear to have been piled up layer by layer, and it is therefore likely that the clay from which they were formed was itself at one time arranged in layers. One layer was formed first, then at a different period, a further was formed and piled, upon the first, and so on. Over each layer there spread a substance of different material, which formed a partition between it and the next layer; but when petrification took place something occurred to the partition which caused it to break up and disintegrate from between the layers (possibly referring to unconformity). ... As to the beginning of the sea, its clay is either sedimentary or primeval, the latter not being sedimentary. It is probable that the sedimentary clay was formed by the disintegration of the strata of mountains. Such is the formation of mountains."

His contemporary, Abū Rayhān Bīrūnī (973-1048), discovered the existence of shells and fossils in regions that once housed seas and later evolved into dry land, such as the Indian subcontinent. Based on this evidence, he realized that the Earth is constantly evolving and proposed that the Earth had an age, but that its origin was too distant to measure.[8] Later in the 11th century, the Chinese naturalist, Shen Kuo (1031-1095), also recognized the concept of 'deep time'.[9]

The principles underlying geologic (geological) time scales were later laid down by Nicholas Steno in the late 17th century. Steno argued that rock layers (or strata) are laid down in succession, and that each represents a "slice" of time. He also formulated the law of superposition, which states that any given stratum is probably older than those above it and younger than those below it. While Steno's principles were simple, applying them to real rocks proved complex. Over the course of the 18th century geologists realized that:

- Sequences of strata were often eroded, distorted, tilted, or even inverted after deposition;

- Strata laid down at the same time in different areas could have entirely different appearances;

- The strata of any given area represented only part of the Earth's long history.

The first serious attempts to formulate a geological time scale that could be applied anywhere on Earth took place in the late 18th century. The most influential of those early attempts (championed by Abraham Werner, among others) divided the rocks of the Earth's crust into four types: Primary, Secondary, Tertiary, and Quaternary. Each type of rock, according to the theory, formed during a specific period in Earth history. It was thus possible to speak of a "Tertiary Period" as well as of "Tertiary Rocks." Indeed, "Tertiary" (now Paleocene-Pliocene) and "Quaternary" (now Pleistocene-Holocene) remained in use as names of geological periods well into the 20th century.

In opposition to the then-popular Neptunist theories expounded by Werner (that all rocks had precipitated out of a single enormous flood), a major shift in thinking came with the reading by James Hutton of his Theory of the Earth; or, an Investigation of the Laws Observable in the Composition, Dissolution, and Restoration of Land Upon the Globe before the Royal Society of Edinburgh in March and April 1785, events which "as things appear from the perspective of the twentieth century, James Hutton in those reading became the founder of modern geology"[10] What Hutton proposed was that the interior of the Earth was hot, and that this heat was the engine which drove the creation of new rock: land was eroded by air and water and deposited as layers in the sea; heat then consolidated the sediment into stone, and uplifted it into new lands. This theory was dubbed "Plutonist" in contrast to the flood-oriented theory.

The identification of strata by the fossils they contained, pioneered by William Smith, Georges Cuvier, Jean d'Omalius d'Halloy and Alexandre Brogniart in the early 19th century, enabled geologists to divide Earth history more precisely. It also enabled them to correlate strata across national (or even continental) boundaries. If two strata (however distant in space or different in composition) contained the same fossils, chances were good that they had been laid down at the same time. Detailed studies between 1820 and 1850 of the strata and fossils of Europe produced the sequence of geological periods still used today.

The process was dominated by British geologists, and the names of the periods reflect that dominance. The "Cambrian," (the Roman name for Wales) and the "Ordovician," and "Silurian", named after ancient Welsh tribes, were periods defined using stratigraphic sequences from Wales.[11] The "Devonian" was named for the English county of Devon, and the name "Carboniferous" was simply an adaptation of "the Coal Measures," the old British geologists' term for the same set of strata. The "Permian" was named after Perm, Russia, because it was defined using strata in that region by a Scottish geologist Roderick Murchison. However, some periods were defined by geologists from other countries. The "Triassic" was named in 1834 by a German geologist Friedrich Von Alberti from the three distinct layers (Latin trias meaning triad) —red beds, capped by chalk, followed by black shales— that are found throughout Germany and Northwest Europe, called the 'Trias'. The "Jurassic" was named by a French geologist Alexandre Brogniart for the extensive marine limestone exposures of the Jura Mountains. The "Cretaceous" (from Latin creta meaning 'chalk') as a separate period was first defined by a Belgian geologist Jean d'Omalius d'Halloy in 1822, using strata in the Paris basin[12] and named for the extensive beds of chalk (calcium carbonate deposited by the shells of marine invertebrates).

British geologists were also responsible for the grouping of periods into Eras and the subdivision of the Tertiary and Quaternary periods into epochs.

When William Smith and Sir Charles Lyell first recognized that rock strata represented successive time periods, time scales could be estimated only very imprecisely since various kinds of rates of change used in estimation were highly variable. While creationists had been proposing dates of around six or seven thousand years for the age of the Earth based on the Bible, early geologists were suggesting millions of years for geologic periods with some even suggesting a virtually infinite age for the Earth. Geologists and paleontologists constructed the geologic table based on the relative positions of different strata and fossils, and estimated the time scales based on studying rates of various kinds of weathering, erosion, sedimentation, and lithification. Until the discovery of radioactivity in 1896 and the development of its geological applications through radiometric dating during the first half of the 20th century (pioneered by such geologists as Arthur Holmes) which allowed for more precise absolute dating of rocks, the ages of various rock strata and the age of the Earth were the subject of considerable debate.

In 1977, the Global Commission on Stratigraphy (now the International Commission on Stratigraphy) started an effort to define global references (Global Boundary Stratotype Sections and Points) for geologic periods and faunal stages. The commission's most recent work is described in the 2004 geologic time scale of Gradstein et al.[13]. A UML model for how the timescale is structured, relating it to the GSSP, is also available[14].

Table of geologic time

The following table summarizes the major events and characteristics of the periods of time making up the geologic time scale. As above, this time scale is based on the International Commission on Stratigraphy. (See lunar geologic timescale for a discussion of the geologic subdivisions of Earth's moon.) The height of each table entry does not correspond to the duration of each subdivision of time.

| Supereon | Eon | Era | Period[15] | Series / Epoch | Stage[16] / Age | Major events | Start, million years ago[16] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phanerozoic | Cenozoic (Tertiary)[17] | Neogene (Tertiary/Quaternary)[17] |

Holocene (Quaternary) | Atlantic | The last glacial period ends and rise of human civilization. Quaternary Ice Age recedes, and the current interglacial begins. Younger Dryas cold spell occurs, Sahara Desert forms from savannah, and agriculture begins, allowing humans to build cities. Paleolithic/Neolithic (Stone Age) cultures begin around 10,000 BC, giving way to Copper Age (3500 BC) and Bronze Age (2500 BC). Cultures continue to grow in complexity and technical advancement through the Iron Age (1200 BC), giving rise to many pre-historic cultures throughout the world, eventually leading into Classical Antiquity, such as Ancient Rome and even to the Middle Ages and present day. Little Ice Age (stadial) causes brief cooling in Northern Hemisphere from 1400 to 1850. Also refer to the List of archaeological periods for clarification on early cultures and ages. Mount Tambora erupts in 1815, causing the Year Without a Summer (1816) in Europe and North America from a volcanic winter. atmospheric CO2 levels start creeping from 100 ppmv at the end of the last glaciation to the current level of 385 parts per million volume (ppmv), causing, according to some sources, global warming and climate change, possibly from anthropogenic sources, such as the Industrial Revolution[18] | 0.011430 ± 0.00013[17][19] | |

| Boreal | |||||||

| Pleistocene (Quaternary) | Late/Tyrrhenian Stage/Eemian/Sangamonian | Flourishing and then extinction of many large mammals (Pleistocene megafauna). Evolution of anatomically modern humans. Quaternary Ice Age continues with glaciations and interstadials (and the accompanying fluctuations from 100 to 300 ppmv in atmospheric Carbon Dioxide levels[18]), further intensification of Icehouse Earth conditions, roughly 1.6 MYA[20]. Last glacial maximum (30,000 years ago), last glacial period (18,000-15,000 years ago). Dawn of human stone-age cultures, with increasing technical complexity than previous ice age cultures, such as engravings and clay statues (Venus of Lespugue), particularly in the Mediterranean and Europe. Lake Toba supervolcano erupts 75,000 years before present, causing a volcanic winter and pushes humanity to the brink of extinction. Pleistocene ends with Oldest Dryas, Older Dryas/Allerød and Younger Dryas climate events, with Younger Dryas forming the boundary with the Holocene. | 0.126 ± 0.005* | ||||

| Middle | 0.500? | ||||||

| Early | 1.806 ± 0.005* | ||||||

| Gelasian | 2.588 ± 0.005* | ||||||

| Pliocene (Quaternary) | Piacenzian/Blancan | Intensification of present Icehouse conditions, Present (Quaternary) ice age begins roughly 2.58 MYA; cool and dry climate. Australopithecines, many of the existing genera of mammals, and recent mollusks appear. Homo habilis appears. | 3.600 ± 0.005* | ||||

| Zanclean | 5.332 ± 0.005* | ||||||

| Miocene (Tertiary) | Messinian | Moderate Icehouse climate, puncuated by ice ages; Orogeny in northern hemisphere. Modern mammal and bird families became recognizable. Horses and mastodons diverse. Grasses become ubiquitous. First apes appear (for reference see the article: "Sahelanthropus tchadensis"). Kaikoura Orogeny forms Southern Alps in New Zealand, continues today. Orogeny of the Alps in Europe slows, but continues to this day. Carpathean orogeny forms Carpathian Mountains in Central and Eastern Europe. Hellenic orogeny in Greece and Aegean Sea slows, but continues to this day. Middle Miocene Disruption occurs. Widespread forests slowly draw in massive amounts of atmospheric Carbon Dioxide, gradually lowering the level atmospheric CO2 from 650 ppmv down to around 100 ppmv[18]. | 7.246 ± 0.05* | ||||

| Tortonian | 11.608 ± 0.05* | ||||||

| Serravallian | 13.65 ± 0.05* | ||||||

| Langhian | 15.97 ± 0.05* | ||||||

| Burdigalian | 20.43 ± 0.05* | ||||||

| Aquitanian | 23.03 ± 0.05* | ||||||

| Paleogene (Tertiary)[17] |

Oligocene (Tertiary) | Chattian | Warm but cooling climate, moving towards Icehouse; Rapid evolution and diversification of fauna, especially mammals. Major evolution and dispersal of modern types of flowering plants | 28.4 ± 0.1* | |||

| Rupelian | 33.9 ± 0.1* | ||||||

| Eocene (Tertiary) |

Priabonian | Moderate, cooling climate. Archaic mammals (e.g. Creodonts, Condylarths, Uintatheres, etc) flourish and continue to develop during the epoch. Appearance of several "modern" mammal families. Primitive whales diversify. First grasses. Reglaciation of Antarctica and formation of its ice cap; Azolla event triggers ice age, and the Icehouse Earth climate that would follow it to this day, from the settlement and decay of seafloor algae drawing in massive amounts of atmospheric Carbon Dioxide[18], lowering it from 3800 ppmv down to 650 ppmv. End of Laramide and Sevier Orogenies of the Rocky Mountains in North America. Orogeny of the Alps in Europe begins. Hellenic Orogeny begins in Greece and Aegean Sea. | 37.2 ± 0.1* | ||||

| Bartonian | 40.4 ± 0.2* | ||||||

| Lutetian | 48.6 ± 0.2* | ||||||

| Ypresian | 55.8 ± 0.2* | ||||||

| Paleocene (Tertiary) | Thanetian | Climate tropical. Modern plants appear; Mammals diversify into a number of primitive lineages following the extinction of the dinosaurs. First large mammals (up to bear or small hippo size). Alpine orogeny in Europe and Asia begins. Indian Subcontinent collides with Asia 55 MYA[20], Himalayan Orogeny starts between 52 and 48 MYA. | 58.7 ± 0.2* | ||||

| Selandian | 61.7 ± 0.3* | ||||||

| Danian | 65.5 ± 0.3* | ||||||

| Mesozoic | Cretaceous | Upper/Late | Maastrichtian | Flowering plants proliferate, along with new types of insects. More modern teleost fish begin to appear. Ammonites, belemnites, rudist bivalves, echinoids and sponges all common. Many new types of dinosaurs (e.g. Tyrannosaurs, Titanosaurs, duck bills, and horned dinosaurs) evolve on land, as do Eusuchia (modern crocodilians); and mosasaurs and modern sharks appear in the sea. Primitive birds gradually replace pterosaurs. Monotremes, marsupials and placental mammals appear. Break up of Gondwana. Beginning of Laramide and Sevier Orogenies of the Rocky Mountains. Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide close to present-day levels. | 70.6 ± 0.6* | ||

| Campanian | 83.5 ± 0.7* | ||||||

| Santonian | 85.8 ± 0.7* | ||||||

| Coniacian | 89.3 ± 1.0* | ||||||

| Turonian | 93.5 ± 0.8* | ||||||

| Cenomanian | 99.6 ± 0.9* | ||||||

| Lower/Early | Albian | 112.0 ± 1.0* | |||||

| Aptian | 125.0 ± 1.0* | ||||||

| Barremian | 130.0 ± 1.5* | ||||||

| Hauterivian | 136.4 ± 2.0* | ||||||

| Valanginian | 140.2 ± 3.0* | ||||||

| Berriasian | 145.5 ± 4.0* | ||||||

| Jurassic | Upper/Late | Tithonian | Gymnosperms (especially conifers, Bennettitales and cycads) and ferns common. Many types of dinosaurs, such as sauropods, carnosaurs, and stegosaurs. Mammals common but small. First birds and lizards. Ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs diverse. Bivalves, Ammonites and belemnites abundant. Sea urchins very common, along with crinoids, starfish, sponges, and terebratulid and rhynchonellid brachiopods. Breakup of Pangaea into Gondwana and Laurasia. Nevadan orogeny in North America. Rantigata and Cimmerian Orogenies taper off. Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide levels 4-5 times the present day levels (1200-1500 ppmv, compared to today's 385 ppmv[18]). | 150.8 ± 4.0* | |||

| Kimmeridgian | 155.7 ± 4.0* | ||||||

| Oxfordian | 161.2 ± 4.0* | ||||||

| Middle | Callovian | 164.7 ± 4.0 | |||||

| Bathonian | 167.7 ± 3.5* | ||||||

| Bajocian | 171.6 ± 3.0* | ||||||

| Aalenian | 175.6 ± 2.0* | ||||||

| Lower/Early | Toarcian | 183.0 ± 1.5* | |||||

| Pliensbachian | 189.6 ± 1.5* | ||||||

| Sinemurian | 196.5 ± 1.0* | ||||||

| Hettangian | 199.6 ± 0.6* | ||||||

| Triassic | Upper/Late | Rhaetian | Archosaurs dominant on land as dinosaurs, in the oceans as Ichthyosaurs and nothosaurs, and in the air as pterosaurs. cynodonts become smaller and more mammal-like, while first mammals and crocodilia appear. Dicrodium flora common on land. Many large aquatic temnospondyl amphibians. Ceratitic ammonoids extremely common. Modern corals and teleost fish appear, as do many modern insect clades. Andean Orogeny in South America. Cimmerian Orogeny in Asia. Rangitata Orogeny begins in New Zealand. Hunter-Bowen Orogeny in Northern Australia, Queensland and New South Wales ends, (c. 260-225 MYA) | 203.6 ± 1.5* | |||

| Norian | 216.5 ± 2.0* | ||||||

| Carnian | 228.0 ± 2.0* | ||||||

| Middle | Ladinian | 237.0 ± 2.0* | |||||

| Anisian | 245.0 ± 1.5* | ||||||

| Lower/Early ("Scythian") | Olenekian | 249.7 ± 1.5* | |||||

| Induan | 251.0 ± 0.7* | ||||||

| Paleozoic | Permian | Lopingian | Changhsingian | Landmasses unite into supercontinent Pangaea, creating the Appalachians. End of Permo-Carboniferous glaciation. Synapsid reptiles (pelycosaurs and therapsids) become plentiful, while parareptiles and temnospondyl amphibians remain common. In the mid-Permian, coal-age flora are replaced by cone-bearing gymnosperms (the first true seed plants) and by the first true mosses. Beetles and flies evolve. Marine life flourishes in warm shallow reefs; productid and spiriferid brachiopods, bivalves, forams, and ammonoids all abundant. Permian-Triassic extinction event occurs 251 mya: 95% of life on Earth becomes extinct, including all trilobites, graptolites, and blastoids. Ouachita and Innuitian orogenies in North America. Uralian orogeny in Europe/Asia tapers off. Altaid orogeny in Asia. Hunter-Bowen Orogeny on Australian Continent begins, (c. 260-225 MYA). Forms the MacDonnell Ranges. | 253.8 ± 0.7* | ||

| Wuchiapingian | 260.4 ± 0.7* | ||||||

| Guadalupian | Capitanian | 265.8 ± 0.7* | |||||

| Wordian/Kazanian | 268.4 ± 0.7* | ||||||

| Roadian/Ufimian | 270.6 ± 0.7* | ||||||

| Cisuralian | Kungurian | 275.6 ± 0.7* | |||||

| Artinskian | 284.4 ± 0.7* | ||||||

| Sakmarian | 294.6 ± 0.8* | ||||||

| Asselian | 299.0 ± 0.8* | ||||||

| Carbon- iferous[21]/ Pennsyl- vanian |

Upper/Late | Gzhelian | Winged insects radiate suddenly; some (esp. Protodonata and Palaeodictyoptera) are quite large. Amphibians common and diverse. First reptiles and coal forests (scale trees, ferns, club trees, giant horsetails, Cordaites, etc.). Highest-ever atmospheric oxygen levels. Goniatites, brachiopods, bryozoa, bivalves, and corals plentiful in the seas and oceans. Testate forams proliferate. Uralian orogeny in Europe and Asia. Variscan orogeny occurs towards middle and late Mississippian Periods. | 303.9 ± 0.9* | |||

| Kasimovian | 306.5 ± 1.0* | ||||||

| Middle | Moscovian | 311.7 ± 1.1* | |||||

| Lower/Early | Bashkirian | 318.1 ± 1.3* | |||||

| Carbon- iferous[21]/ Missis- sippian |

Upper/Late | Serpukhovian | Large primitive trees, first land vertebrates, and amphibious sea-scorpions live amid coal-forming coastal swamps. Lobe-finned rhizodonts are dominant big fresh-water predators. In the oceans, early sharks are common and quite diverse; echinoderms (especially crinoids and blastoids) abundant. Corals, bryozoa, goniatites and brachiopods (Productida, Spiriferida, etc.) very common. But trilobites and nautiloids decline. Glaciation in East Gondwana. Tuhua Orogeny in New Zealand tapers off. | 326.4 ± 1.6* | |||

| Middle | Viséan | 345.3 ± 2.1* | |||||

| Lower/Early | Tournaisian | 359.2 ± 2.5* | |||||

| Devonian | Upper/Late | Famennian | First clubmosses, horsetails and ferns appear, as do the first seed-bearing plants (progymnosperms), first trees (the progymnosperm Archaeopteris), and first (wingless) insects. Strophomenid and atrypid brachiopods, rugose and tabulate corals, and crinoids are all abundant in the oceans. Goniatite ammonoids are plentiful, while squid-like coleoids arise. Trilobites and armoured agnaths decline, while jawed fishes (placoderms, lobe-finned and ray-finned fish, and early sharks) rule the seas. First amphibians still aquatic. "Old Red Continent" of Euramerica. Beginning of Acadian Orogeny for Anti-Atlas Mountains of North Africa, and Appalachian Mountains of North America, also the Antler, Variscan, and Tuhua Orogeny in New Zealand. | 374.5 ± 2.6* | |||

| Frasnian | 385.3 ± 2.6* | ||||||

| Middle | Givetian | 391.8 ± 2.7* | |||||

| Eifelian | 397.5 ± 2.7* | ||||||

| Lower/Early | Emsian | 407.0 ± 2.8* | |||||

| Pragian | 411.2 ± 2.8* | ||||||

| Lochkovian | 416.0 ± 2.8* | ||||||

| Silurian | Pridoli | no faunal stages defined | First Vascular plants (the rhyniophytes and their relatives), first millipedes and arthropleurids on land. First jawed fishes, as well as many armoured jawless fish, populate the seas. Sea-scorpions reach large size. Tabulate and rugose corals, brachiopods (Pentamerida, Rhynchonellida, etc.), and crinoids all abundant. Trilobites and mollusks diverse; graptolites not as varied. Beginning of Caledonian Orogeny for hills in England, Ireland, Wales, Scotland, and the Scandinavian Mountains. Also continued into Devonian period as the Acadian Orogeny, above. Taconic Orogeny tapers off. Lachlan Orogeny on Australian Continent tapers off. | 418.7 ± 2.7* | |||

| Ludlow/Cayugan | Ludfordian | 421.3 ± 2.6* | |||||

| Gorstian | 422.9 ± 2.5* | ||||||

| Wenlock | Homerian/Lockportian | 426.2 ± 2.4* | |||||

| Sheinwoodian/Tonawandan | 428.2 ± 2.3* | ||||||

| Llandovery/ Alexandrian |

Telychian/Ontarian | 436.0 ± 1.9* | |||||

| Aeronian | 439.0 ± 1.8* | ||||||

| Rhuddanian | 443.7 ± 1.5* | ||||||

| Ordovician | Upper/Late | Hirnantian | Invertebrates diversify into many new types (e.g., long straight-shelled cephalopods). Early corals, articulate brachiopods (Orthida, Strophomenida, etc.), bivalves, nautiloids, trilobites, ostracods, bryozoa, many types of echinoderms (crinoids, cystoids, starfish, etc.), branched graptolites, and other taxa all common. Conodonts (early planktonic vertebrates) appear. First green plants and fungi on land. Ice age at end of period. | 445.6 ± 1.5* | |||

| other faunal stages | 460.9 ± 1.6* | ||||||

| Middle | Darriwilian | 468.1 ± 1.6* | |||||

| other faunal stages | 471.8 ± 1.6* | ||||||

| Lower/Early | Arenig | 478.6 ± 1.7* | |||||

| Tremadocian | 488.3 ± 1.7* | ||||||

| Cambrian | Furongian | other faunal stages | Major diversification of life in the Cambrian Explosion. Many fossils; most modern animal phyla appear. First chordates appear, along with a number of extinct, problematic phyla. Reef-building Archaeocyatha abundant; then vanish. Trilobites, priapulid worms, sponges, inarticulate brachiopods (unhinged lampshells), and many other animals numerous. Anomalocarids are giant predators, while many Ediacaran fauna die out. Prokaryotes, protists (e.g., forams), fungi and algae continue to present day. Gondwana emerges. Petermann Orogeny on the Australian Continent tapers off (550-535 MYA). Ross Orogeny in Antarctica. Adelaide Geosyncline (Delamerian Orogeny), majority of orogenic activity from 514-500 MYA. Lachlan Orogeny on Australian Continent, c. 540-440 MYA. Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide content roughly 20-35 times present-day (Holocene) levels (6000 ppmv compared to today's 385 ppmv)[18] | 496.0 ± 2.0* | |||

| Paibian/Ibexian/ Ayusokkanian/Sakian/ Aksayan |

501.0 ± 2.0* | ||||||

| Middle | other faunal stages/Albertan | 513.0 ± 2.0 | |||||

| Lower/Early | other faunal stages/ Waucoban/Tommotian/ Atdabanian/Botomian |

542.0 ± 1.0* | |||||

| Precam- brian[22] |

Proter- ozoic[23] |

Neo- proterozoic[23] |

Ediacaran | Good fossils of the first multi-celled animals. Ediacaran biota flourish worldwide in seas. Simple trace fossils of possible worm-like Trichophycus, etc. First sponges and trilobitomorphs. Enigmatic forms include many soft-jellied creatures shaped like bags, disks, or quilts (like Dickinsonia). Taconic Orogeny in North America. Aravalli Range orogeny in Indian Subcontinent. Beginning of Petermann Orogeny on Australian Continent. Beardmore Orogeny in Antarctica, 633-620 MYA. | 630 +5/-30* | ||

| Cryogenian | Possible "Snowball Earth" period. Fossils still rare. Rodinia landmass begins to break up. Late Ruker / Nimrod Orogeny in Antarctica tapers off. | 850[24] | |||||

| Tonian | Rodinia supercontinent persists. Trace fossils of simple multi-celled eukaryotes. First radiation of dinoflagellate-like acritarchs. Grenville Orogeny tapers off in North America. Pan-African Orogeny in Africa. Lake Ruker / Nimrod Orogeny in Antarctica, 1000 ± 150 MYA. Edmundian Orogeny (c. 920 - 850 MYA), Gascoyne Complex, Western Australia. Adelaide Geosyncline laid down on Australian Continent, beginning of Adelaide Geosyncline (Delamerian Orogeny) in that continent. | 1000[24] | |||||

| Meso- proterozoic[23] |

Stenian | Narrow highly metamorphic belts due to orogeny as Rodinia formed. Late Ruker / Nimrod Orogeny in Antarctica possibly begins. Musgrave Orogeny (c. 1080 MYA), Musgrave Block, Central Australia. | 1200[24] | ||||

| Ectasian | Platform covers continue to expand. Green algae colonies in the seas. Grenville Orogeny in North America. | 1400[24] | |||||

| Calymmian | Platform covers expand. Barramundi Orogeny, MacArthur Basin, Northern Australia, and Isan Orogeny, c. 1600 MYA, Mount Isa Block, Queensland | 1600[24] | |||||

| Paleo- proterozoic[23] |

Statherian | First complex single-celled life: protists with nuclei. Columbia is the primordial supercontinent. Kimban Orogeny in Australian Continent ends. Yapungku Orogeny on North Yilgarn craton, in Western Australia. Mangaroon Orogeny, 1680-1620 MYA, on the Gascoyne Complex in Western Australia. Kararan Orogeny (1650- MYA), Gawler Craton, South Australia. | 1800[24] | ||||

| Orosirian | The atmosphere became oxygenic. Vredefort and Sudbury Basin asteroid impacts. Much orogeny. Penokean and Trans-Hudsonian Orogenies in North America. Early Ruker Orogeny in Antarctica, 2000 - 1700 MYA. Glenburgh Orogeny, Glenburgh Terrane, Australian Continent c. 2005 - 1920 MYA. Kimban Orogeny, Gawler craton in Australian Continent begins. | 2050[24] | |||||

| Rhyacian | Bushveld Formation formed. Huronian glaciation. | 2300[24] | |||||

| Siderian | Oxygen Catastrophe: banded iron formations formed. Sleaford Orogeny on Australian Continent, Gawler Craton 2440-2420 MYA. | 2500[24] | |||||

| Archean[23] | Neoarchean[23] | Stabilization of most modern cratons; possible mantle overturn event. Insell Orogeny, 2650 ± 150 MYA. Abitibi greenstone belt in present-day Ontario and Quebec begins to form, stablizes by 2600 MYA. | 2800[24] | ||||

| Mesoarchean[23] | First stromatolites (probably colonial cyanobacteria). Oldest macrofossils. Humboldt Orogeny in Antarctica. Blake River Megacaldera Complex begins to form in present-day Ontario and Quebec, ends by roughly 2696 MYA. | 3200[24] | |||||

| Paleoarchean[23] | First known oxygen-producing bacteria. Oldest definitive microfossils. Oldest cratons on earth (such as the Canadian Shield and the Pilbara Craton) may have formed during this period[25]. Rayner Orogeny in Antarctica. | 3600[24] | |||||

| Eoarchean[23] | Simple single-celled life (probably bacteria and perhaps archaea). Oldest probable microfossils. | 3800 | |||||

| Hadean [23][26] |

Lower Imbrian[23][27] | This era overlaps the end of the Late Heavy Bombardment of the inner solar system. | c.3850 | ||||

| Nectarian[23][27] | This era gets its name from the lunar geologic timescale when the Nectaris Basin and other major lunar basins were formed by large impact events. | c.3920 | |||||

| Basin Groups[23][27] | Oldest known rock (4030 Ma)[28]. The first Lifeforms and self-replicating RNA molecules may have evolved on earth around 4000 Ma during this era. Naiper Orogeny in Antarctica, 4000 ± 200 MYA. | c.4150 | |||||

| Cryptic[23][27] | Oldest known mineral (Zircon, 4406±8 Ma[29]). Formation of Moon (4533 Ma), probably from giant impact. Formation of Earth (4567.17 to 4570 Ma) | c.4570 | |||||

- ↑ International Commission on Stratigraphy. "International Stratigraphic Chart". Retrieved on 2008-06-17.

- ↑ Geologic Time Scale

- ↑ How the discovery of geologic time changed our view of the world, Bristol University

- ↑ Correlating Earth's History, Paul R. Janke

- ↑ Intute Timeline - Fossils (Subject: Science Engineering and Technology)

- ↑ Munim M. Al-Rawi and Salim Al-Hassani (November 2002). "The Contribution of Ibn Sina (Avicenna) to the development of Earth sciences". FSTC. Retrieved on 2008-07-01.

- ↑ Stephen Toulmin and June Goodfield (1965), The Ancestry of Science: The Discovery of Time, p. 64, University of Chicago Press (cf. The Contribution of Ibn Sina to the development of Earth sciences)

- ↑ Scheppler, Bill (2006), Al-Biruni: Master Astronomer and Muslim Scholar of the Eleventh Century, The Rosen Publishing Group, 86, ISBN 1404205128

- ↑ Sivin, Nathan (1995). Science in Ancient China: Researches and Reflections. Brookfield, Vermont: Ashgate Publishing Variorum series. III, 23–24.

- ↑ John McPhee, Basin and Range, New York:Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1981, pp.95-100.

- ↑ John McPhee, Basin and Range, pp.113-114.

- ↑ (in Russian)Great Soviet Encyclopedia (3rd ed. ed.). Moscow: Sovetskaya Enciklopediya. 1974. vol. 16, p. 50.

- ↑ Felix M. Gradstein, James G. Ogg, Alan G. Smith (Editors); A Geologic Time Scale 2004, Cambridge University Press, 2005, (ISBN 0-521-78673-8)

- ↑ Cox & Richard, A formal model for the geologic time scale and global stratotype section and point, compatible with geospatial information transfer standards, Geosphere, volume 1, pp 119-137, Geological Society of America, 2005

- ↑ Paleontologists often refer to faunal stages rather than geologic (geological) periods. The stage nomenclature is quite complex. See "The Paleobiology Database". Retrieved on 2006-03-19. for an excellent time ordered list of faunal stages.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Dates are slightly uncertain with differences of a few percent between various sources being common. This is largely due to uncertainties in radiometric dating and the problem that deposits suitable for radiometric dating seldom occur exactly at the places in the geologic column where they would be most useful. The dates and errors quoted above are according to the International Commission on Stratigraphy 2004 time scale. Dates labeled with a * indicate boundaries where a Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point has been internationally agreed upon: see List of Global Boundary Stratotype Sections and Points for a complete list.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Historically, the Cenozoic has been divided up into the Quaternary and Tertiary sub-eras, as well as the Neogene and Paleogene periods. However, the International Commission on Stratigraphy has recently decided to stop endorsing the terms Quaternary and Tertiary as part of the formal nomenclature.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 For more information on this, see the following articles: Earth's atmosphere, Carbon Dioxide, Carbon dioxide in the Earth's atmosphere, Image:Phanerozoic_Carbon_Dioxide.png, Image:65 Myr Climate Change.png, Image:Five Myr Climate Change.png, and

- ↑ The start time for the Holocene epoch is here given as 11,430 years ago ± 130 years (that is, between 9610 BC-9560 BC and 9350 BC-9300 BC). For further discussion of the dating of this epoch, see Holocene.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 MYA = Million Years Ago

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 In North America, the Carboniferous is subdivided into Mississippian and Pennsylvanian Periods.

- ↑ The Precambrian is also known as Cryptozoic.

- ↑ 23.00 23.01 23.02 23.03 23.04 23.05 23.06 23.07 23.08 23.09 23.10 23.11 23.12 23.13 The Proterozoic, Archean and Hadean are often collectively referred to as the Precambrian Time or sometimes, also the Cryptozoic.

- ↑ 24.00 24.01 24.02 24.03 24.04 24.05 24.06 24.07 24.08 24.09 24.10 24.11 Defined by absolute age (Global Standard Stratigraphic Age).

- ↑ The age of the oldest measurable craton, or continental crust, is dated to 3600-3800 Ma

- ↑ Though commonly used, the Hadean is not a formal eon and no lower bound for the Archean and Eoarchean have been agreed upon. The Hadean has also sometimes been called the Priscoan or the Azoic. Sometimes, the Hadean can be found to be subdivided according to the lunar geologic time scale. These eras include the Cryptic and Basin Groups (which are subdivisions of the pre-Nectarian era), Nectarian, and Lower Imbrian eras.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 These era names were taken from the Lunar geologic timescale. Their use for Earth geology is unofficial.

- ↑ Oldest rock on earth is the Acasta Gneiss, and it dates to 4.03 Ga, located in the Northwest Territories of Canada.

- ↑ http://www.geology.wisc.edu/%7Evalley/zircons/Wilde2001Nature.pdf

See also

- Age of the Earth

- Anthropocene

- Cosmological timeline

- Deep time

- Geological history of Earth

- Graphical timeline of our universe

- History of Earth

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- Logarithmic timeline

- Lunar geologic timescale

- Martian geologic timescale

- Natural history

- Timeline of human evolution

- Time line of the geologic history of the United States

- Timetable of the Precambrian

- New Zealand geologic time scale

- Timeline of evolution

External links

- NASA: Geologic Time

- GSA: Geologic Time Scale

- British Geological Survey: Geological Timechart

- GeoWhen Database

- International Commission on Stratigraphy Time Scale

- CHRONOS

- National Museum of Natural History - Geologic Time

- SeeGrid: Geological Time Systems Information model for the geologic time scale

- Exploring Time from Planck Time to the lifespan of the universe

References and footnotes

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||