English language

| English | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation: | /ˈɪŋɡlɪʃ/[1] | |

| Spoken in: | the Anglosphere (see below) | |

| Total speakers: | First language: 309–400 million Second language: 199–1,400 million[2][3] Overall: 1.8 billion[3] |

|

| Ranking: | 3 (native speakers)[4] Total: 1 or 2 [5] |

|

| Language family: | Indo-European Germanic West Germanic Anglo–Frisian Anglic English |

|

| Writing system: | Latin (English variant) | |

| Official status | ||

| Official language in: | 53 countries |

|

| Regulated by: | No official regulation | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1: | en | |

| ISO 639-2: | eng | |

| ISO 639-3: | eng | |

|

||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

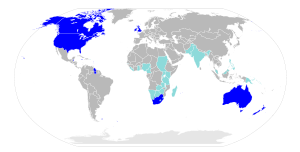

English is a West Germanic language originating in England and is the first language for most people in the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Ireland and the Anglophone Caribbean. It is used extensively as a second language and as an official language throughout the world, especially in Commonwealth countries and in many international organisations.

Contents |

Significance

Modern English, sometimes described as the first global lingua franca,[6][7] is the dominant international language in communications, science, business, aviation, entertainment, radio and diplomacy.[8] The initial reason for its enormous spread beyond the bounds of the British Isles, where it was originally a native tongue, was the British Empire, and by the late nineteenth century its reach was truly global.[9] It is the dominant language in the United States, whose growing economic and cultural influence and status as a global superpower since World War II have significantly accelerated adoption of English as a language across the planet.[7]

A working knowledge of English has become a requirement in a number of fields, occupations and professions such as medicine and as a consequence over a billion people speak English to at least a basic level (see English language learning and teaching).

Linguists such as David Crystal recognize that one impact of this massive growth of English, in common with other global languages, has been to reduce native linguistic diversity in many parts of the world historically, most particularly in Australasia and North America, and its huge influence continues to play an important role in language attrition. By a similar token, historical linguists, aware of the complex and fluid dynamics of language change, are always alive to the potential English contains through the vast size and spread of the communities that use it and its natural internal variety, such as in its creoles and pidgins, to produce a new family of distinct languages over time.

English is one of six official languages of the United Nations.

History

English is a West Germanic language that originated from the Anglo-Frisian and Lower Saxon dialects brought to Britain by Germanic settlers and Roman auxiliary troops from various parts of what is now northwest Germany and the Northern Netherlands. One of these German tribes were the Angles[10], who may have come from Angeln, and Bede wrote that their whole nation came to Britain [11], leaving their former land empty. The names 'England' (or 'Aenglaland') and English are derived from from the name of this tribe.

The Anglo Saxons began invading around 449 AD from the regions of Denmark and Jutland[12][13]. Before the Anglo-Saxons arrived in England the local language was Celtic[14]. Although the most significant changes in dialect occurred after the Norman invasion of 1066, the language retained its name and the pre-Norman invasion dialect is now known as Old English[15].

Initially, Old English was a diverse group of dialects, reflecting the varied origins of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms of Great Britain. One of these dialects, Late West Saxon, eventually came to dominate. The original Old English language was then influenced by two waves of invasion. The first was by language speakers of the Scandinavian branch of the Germanic family; they conquered and colonized parts of the British Isles in the 8th and 9th centuries. The second was the Normans in the 11th century, who spoke Old Norman and ultimately developed an English variety of this called Anglo-Norman. These two invasions caused English to become "mixed" to some degree (though it was never a truly mixed language in the strict linguistic sense of the word; mixed languages arise from the cohabitation of speakers of different languages, who develop a hybrid tongue for basic communication).

Cohabitation with the Scandinavians resulted in a significant grammatical simplification and lexical supplementation of the Anglo-Frisian core of English; the later Norman occupation led to the grafting onto that Germanic core of a more elaborate layer of words from the Italic branch of the European languages. This Norman influence entered English largely through the courts and government. Thus, English developed into a "borrowing" language of great flexibility and with a huge vocabulary.

The emergence and spread of the British Empire and the emergence of the United States as a superpower helped to spread the English language around the world.

The English language belongs to the western sub-branch of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European family of languages. The closest living relative of English is Scots, spoken primarily in Scotland and parts of Northern Ireland, which is viewed by linguists as either a separate language or a group of dialects of English. The next closest relative to English after Scots is Frisian, spoken in the Northern Netherlands and Northwest Germany, followed by the other West Germanic languages (Dutch and Afrikaans, Low German, German), and then the North Germanic languages (Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, Icelandic, and Faroese). With the exception of Scots, none of these languages are mutually intelligible with English, because of divergences in lexis, syntax, semantics, and phonology.

Lexical differences with the other Germanic languages arise predominately because of the heavy usage of Latin (for example, "exit", vs. Dutch uitgang) and French ("change" vs. German Änderung, "movement" vs. German Bewegung) words in English. The syntax of German and Dutch is also significantly different from English, with different rules for setting up sentences (for example, German Ich habe noch nie etwas auf dem Platz gesehen, vs. English "I have still never seen anything in the square"). Semantics causes a number of false friends between English and its relatives. Phonology differences obscure words which actually are genetically related ("enough" vs. German genug), and sometimes both semantics and phonology are different (German Zeit, "time", is related to English "tide", but the English word has come to mean gravitational effects on the ocean by the moon).

Many written French words are also intelligible to an English speaker (though pronunciations are often quite different) because English absorbed a large vocabulary from Norman and French, via Anglo-Norman after the Norman Conquest and directly from French in subsequent centuries. As a result, a large portion of English vocabulary is derived from French, with some minor spelling differences (word endings, use of old French spellings, etc.), as well as occasional divergences in meaning of so-called false friends. The pronunciation of most French loanwords in English (with exceptions such as mirage or phrases like coup d’état) has become completely anglicized and follows a typically English pattern of stress. Some North Germanic words also entered English due to the Danish invasion shortly before then (see Danelaw); these include words such as "sky", "window", "egg", and even "they" (and its forms) and "are" (the present plural form of "to be").

Geographical distribution

- See also: List of countries by English-speaking population

|

||||||||

Approximately 375 million people speak English as their first language.[16] English today is probably the third largest language by number of native speakers, after Mandarin Chinese and Spanish.[17][18] However, when combining native and non-native speakers it is probably the most commonly spoken language in the world, though possibly second to a combination of the Chinese languages, depending on whether or not distinctions in the latter are classified as "languages" or "dialects."[5][19] Estimates that include second language speakers vary greatly from 470 million to over a billion depending on how literacy or mastery is defined.[20][21] There are some who claim that non-native speakers now outnumber native speakers by a ratio of 3 to 1.[22]

The countries with the highest populations of native English speakers are, in descending order: United States (215 million),[23] United Kingdom (58 million),[24] Canada (18.2 million),[25] Australia (15.5 million),[26] Ireland (3.8 million),[24] South Africa (3.7 million),[27] and New Zealand (3.0-3.7 million).[28] Countries such as Jamaica and Nigeria also have millions of native speakers of dialect continua ranging from an English-based creole to a more standard version of English. Of those nations where English is spoken as a second language, India has the most such speakers ('Indian English') and linguistics professor David Crystal claims that, combining native and non-native speakers, India now has more people who speak or understand English than any other country in the world.[29] Following India is the People's Republic of China.[30]

Countries in order of total speakers

| Rank | Country | Total | Percent of population | First language | As an additional language | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States | 251,388,301 | 83% | 215,423,557 | 35,964,744 | Source: US Census 2006: Language Use and English-Speaking Ability: 2006, Table 1. Figure for second language speakers are respondents who reported they do not speak English at home but know it "very well" or "well". Note: figures are for population age 5 and older |

| 2 | India | 90,000,000 | 8% | 178,598 | 65,000,000 second language speakers. 25,000,000 third language speakers |

Figures include both those who speak English as a second language and those who speak it as a third language. 1991 figures.[31][32] The figures include English speakers, but not English users.[33] |

| 3 | Nigeria | 79,000,000 | 53% | 4,000,000 | >75,000,000 | Figures are for speakers of Nigerian Pidgin, an English-based pidgin or creole. Ihemere gives a range of roughly 3 to 5 million native speakers; the midpoint of the range is used in the table. Ihemere, Kelechukwu Uchechukwu. 2006. "A Basic Description and Analytic Treatment of Noun Clauses in Nigerian Pidgin." Nordic Journal of African Studies 15(3): 296–313. |

| 4 | United Kingdom | 59,600,000 | 98% | 58,100,000 | 1,500,000 | Source: Crystal (2005), p. 109. |

| 5 | Philippines | 45,900,000 | 52% | 27,000 | 42,500,000 | Total speakers: Census 2000, text above Figure 7. 63.71% of the 66.7 million people aged 5 years or more could speak English. Native speakers: Census 1995, as quoted by Andrew Gonzalez in The Language Planning Situation in the Philippines, Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 19 (5&6), 487-525. (1998) |

| 6 | Canada | 25,246,220 | 76% | 17,694,830 | 7,551,390 | Source: 2001 Census - Knowledge of Official Languages and Mother Tongue. The native speakers figure comprises 122,660 people with both French and English as a mother tongue, plus 17,572,170 people with English and not French as a mother tongue. |

| 7 | Australia | 18,172,989 | 92% | 15,581,329 | 2,591,660 | Source: 2006 Census.[34] The figure shown in the first language English speakers column is actually the number of Australian residents who speak only English at home. The additional language column shows the number of other residents who claim to speak English "well" or "very well". Another 5% of residents did not state their home language or English proficiency. |

English is the primary language in Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Australia (Australian English), the Bahamas, Barbados, Bermuda, Belize (Belizean Kriol), the British Indian Ocean Territory, the British Virgin Islands, Canada (Canadian English), the Cayman Islands, the Falkland Islands, Gibraltar, Grenada, Guam, Guernsey (Channel Island English), Guyana, Ireland (Hiberno-English), Isle of Man (Manx English), Jamaica (Jamaican English), Jersey, Montserrat, Nauru, New Zealand (New Zealand English), Pitcairn Islands, Saint Helena, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Singapore, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, Trinidad and Tobago, the Turks and Caicos Islands, the United Kingdom, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the United States.

In many other countries, where English is not the most spoken language, it is an official language; these countries include Botswana, Cameroon, Dominica, Fiji, the Federated States of Micronesia, Ghana, Gambia, India, Kenya, Kiribati, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malta, the Marshall Islands, Mauritius, Namibia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Palau, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines (Philippine English), Puerto Rico, Rwanda, the Solomon Islands, Saint Lucia, Samoa, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. It is also one of the 11 official languages that are given equal status in South Africa (South African English). English is also the official language in current dependent territories of Australia (Norfolk Island, Christmas Island and Cocos Island) and of the United States (Northern Mariana Islands, American Samoa and Puerto Rico)[35], former British colony of Hong Kong, and Netherlands Antilles.

English is an important language in several former colonies and protectorates of the United Kingdom but falls short of official status, such as in Malaysia, Brunei, United Arab Emirates and Bahrain. English is also not an official language in either the United States or the United Kingdom.[36][37] Although the United States federal government has no official languages, English has been given official status by 30 of the 50 state governments.[38] English is not a de jure official language of Israel; however, the country has maintained official language use a de facto role for English since the British mandate.[39]

English as a global language

- See also: English in computing, International English, and World language

Because English is so widely spoken, it has often been referred to as a "world language," the lingua franca of the modern era.[7] While English is not an official language in most countries, it is currently the language most often taught as a second language around the world. Some linguists believe that it is no longer the exclusive cultural sign of "native English speakers", but is rather a language that is absorbing aspects of cultures worldwide as it continues to grow. It is, by international treaty, the official language for aerial and maritime communications. English is an official language of the United Nations and many other international organizations, including the International Olympic Committee.

English is the language most often studied as a foreign language in the European Union (by 89% of schoolchildren), followed by French (32%), German (18%), and Spanish (8%).[40] In the EU, a large fraction of the population reports being able to converse to some extent in English. Among non-English speaking countries, a large percentage of the population claimed to be able to converse in English in the Netherlands (87%), Sweden (85%), Denmark (83%), Luxembourg (66%), Finland (60%), Slovenia (56%), Austria (53%), Belgium (52%), and Germany (51%).[41] Norway and Iceland also have a large majority of competent English-speakers.

Books, magazines, and newspapers written in English are available in many countries around the world. English is also the most commonly used language in the sciences.[7] In 1997, the Science Citation Index reported that 95% of its articles were written in English, even though only half of them came from authors in English-speaking countries.

Dialects and regional varieties

The expansion of the British Empire and—since WWII—the primacy of the United States have spread English throughout the globe.[7] Because of that global spread, English has developed a host of English dialects and English-based creole languages and pidgins.

The major varieties of English include, in most cases, several subvarieties, such as Cockney within British English; Newfoundland English within Canadian English; and African American Vernacular English ("Ebonics") and Southern American English within American English. English is a pluricentric language, without a central language authority like France's Académie française; and, although no variety is clearly considered the only standard, there are a number of accents considered to be more prestigious, such as Received Pronunciation in Britain.

Scots developed—largely independently—from the same origins, but following the Acts of Union 1707 a process of language attrition began, whereby successive generations adopted more and more features from English causing dialectalisation. Whether it is now a separate language or a dialect of English better described as Scottish English is in dispute. The pronunciation, grammar and lexis of the traditional forms differ, sometimes substantially, from other varieties of English.

Because of the wide use of English as a second language, English speakers have many different accents, which often signal the speaker's native dialect or language. For the more distinctive characteristics of regional accents, see Regional accents of English, and for the more distinctive characteristics of regional dialects, see List of dialects of the English language.

Just as English itself has borrowed words from many different languages over its history, English loanwords now appear in a great many languages around the world, indicative of the technological and cultural influence of its speakers. Several pidgins and creole languages have formed using an English base, such as Jamaican Patois, Nigerian Pidgin, and Tok Pisin. There are many words in English coined to describe forms of particular non-English languages that contain a very high proportion of English words. Franglais, for example, describes various mixes of French and English, spoken in the Channel Islands and Canada. In Wales, which is part of the United Kingdom, the languages of Welsh and English are sometimes mixed together by fluent or comfortable Welsh speakers, the result of which is called Wenglish.

Constructed varieties of English

- Basic English is simplified for easy international use. Manufacturers and other international businesses to write manuals and communicate use it. Some English schools in Asia teach it as a practical subset of English for use by beginners.

- Special English is a simplified version of English used by the Voice of America. It uses a vocabulary of only 1500 words.

- English reform is an attempt to improve collectively upon the English language.

- Seaspeak and the related Airspeak and Policespeak, all based on restricted vocabularies, were designed by Edward Johnson in the 1980s to aid international cooperation and communication in specific areas. There is also a tunnelspeak for use in the Channel Tunnel.

- Euro-English is a concept of standardising English for use as a second language in continental Europe.

- Manually Coded English – a variety of systems have been developed to represent the English language with hand signals, designed primarily for use in deaf education. These should not be confused with true sign languages such as British Sign Language and American Sign Language used in Anglophone countries, which are independent and not based on English.

- E-Prime excludes forms of the verb to be.

Euro-English (also EuroEnglish or Euro-English) terms are English translations of European concepts that are not native to English-speaking countries. Because of the United Kingdom's (and even the Republic of Ireland's) involvement in the European Union, the usage focuses on non-British concepts. This kind of Euro-English was parodied when English was "made" one of the constituent languages of Europanto.

Phonology

Vowels

| IPA | Description | word |

|---|---|---|

| monophthongs | ||

| i/iː | Close front unrounded vowel | bead |

| ɪ | Near-close near-front unrounded vowel | bid |

| ɛ | Open-mid front unrounded vowel | bed |

| æ | Near-open front unrounded vowel | bad |

| ɒ | Open back rounded vowel | box1 |

| ɔ/ɑ | Open-mid back rounded vowel | pawed2 |

| ɑ/ɑː | Open back unrounded vowel | bra |

| ʊ | Near-close near-back vowel | good |

| u/uː | Close back rounded vowel | booed |

| ʌ/ɐ/ɘ | Open-mid back unrounded vowel, near-open central vowel | bud |

| ɝ/ɜː | Open-mid central unrounded vowel | bird3 |

| ə | Schwa | Rosa's4 |

| ɨ | Close central unrounded vowel | roses5 |

| diphthongs | ||

| e(ɪ)/eɪ | Close-mid front unrounded vowel Close front unrounded vowel |

bayed6 |

| o(ʊ)/əʊ | Close-mid back rounded vowel Near-close near-back vowel |

bode6 |

| aɪ | Open front unrounded vowel Near-close near-front unrounded vowel |

cry |

| aʊ | Open front unrounded vowel Near-close near-back vowel |

bough |

| ɔɪ | Open-mid back rounded vowel Close front unrounded vowel |

boy |

| ʊɚ/ʊə | Near-close near-back vowel Schwa |

boor9 |

| ɛɚ/ɛə/eɚ | Open-mid front unrounded vowel Schwa |

fair10 |

Notes:

It is the vowels that differ most from region to region.

Where symbols appear in pairs, the first corresponds to American English, General American accent; the second corresponds to British English, Received Pronunciation.

- American English lacks this sound; words with this sound are pronounced with /ɑ/ or /ɔ/. See Lot-cloth split.

- Some dialects of North American English do not have this vowel. See Cot-caught merger.

- The North American variation of this sound is a rhotic vowel.

- Many speakers of North American English do not distinguish between these two unstressed vowels. For them, roses and Rosa's are pronounced the same, and the symbol usually used is schwa /ə/.

- This sound is often transcribed with /i/ or with /ɪ/.

- The diphthongs /eɪ/ and /oʊ/ are monophthongal for many General American speakers, as /eː/ and /oː/.

- The letter <U> can represent either /u/ or the iotated vowel /ju/. In BRP, if this iotated vowel /ju/ occurs after /t/, /d/, /s/ or /z/, it often triggers palatalization of the preceding consonant, turning it to /ʨ/, /ʥ/, /ɕ/ and /ʑ/ respectively, as in tune, during, sugar, and azure. In American English, palatalization does not generally happen unless the /ju/ is followed by r, with the result that /(t, d,s, z)jur/ turn to /tʃɚ/, /dʒɚ/, /ʃɚ/ and /ʒɚ/ respectively, as in nature, verdure, sure, and treasure.

- Vowel length plays a phonetic role in the majority of English dialects, and is said to be phonemic in a few dialects, such as Australian English and New Zealand English. In certain dialects of the modern English language, for instance General American, there is allophonic vowel length: vowel phonemes are realized as long vowel allophones before voiced consonant phonemes in the coda of a syllable. Before the Great Vowel Shift, vowel length was phonemically contrastive.

- This sound only occurs in non-rhotic accents. In some accents, this sound may be /ɔː/ instead of /ʊə/. See English-language vowel changes before historic r.

- This sound only occurs in non-rhotic accents. In some accents, the schwa offglide of /ɛə/ may be dropped, monophthising and lengthening the sound to /ɛː/.

See also IPA chart for English dialects for more vowel charts.

Consonants

This is the English consonantal system using symbols from the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Labial- velar |

Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ 1 | ||||||

| Plosive | p b | t d | k ɡ | ||||||

| Affricate | tʃ dʒ 4 | ||||||||

| Fricative | f v | θ ð 3 | s z | ʃ ʒ 4 | ç 5 | x 6 | h | ||

| Flap | ɾ 2 | ||||||||

| Approximant | ɹ 4 | j | ʍ w 7 | ||||||

| Lateral | l |

- The velar nasal [ŋ] is a non-phonemic allophone of /n/ in some northerly British accents, appearing only before /k/ and /g/. In all other dialects it is a separate phoneme, although it only occurs in syllable codas.

- The alveolar tap [ɾ] is an allophone of /t/ and /d/ in unstressed syllables in North American English and Australian English.[42] This is the sound of tt or dd in the words latter and ladder, which are homophones for many speakers of North American English. In some accents such as Scottish English and Indian English it replaces /ɹ/. This is the same sound represented by single r in most varieties of Spanish.

- In some dialects, such as Cockney, the interdentals /θ/ and /ð/ are usually merged with /f/ and /v/, and in others, like African American Vernacular English, /ð/ is merged with dental /d/. In some Irish varieties, /θ/ and /ð/ become the corresponding dental plosives, which then contrast with the usual alveolar plosives.

- The sounds /ʃ/, /ʒ/, and /ɹ/ are labialised in some dialects. Labialisation is never contrastive in initial position and therefore is sometimes not transcribed. Most speakers of General American realize <r> (always rhoticized) as the retroflex approximant /ɻ/, whereas the same is realized in Scottish English, etc. as the alveolar trill.

- The voiceless palatal fricative /ç/ is in most accents just an allophone of /h/ before /j/; for instance human /çjuːmən/. However, in some accents (see this), the /j/ is dropped, but the initial consonant is the same.

- The voiceless velar fricative /x/ is used by Scottish or Welsh speakers of English for Scots/Gaelic words such as loch /lɒx/ or by some speakers for loanwords from German and Hebrew like Bach /bax/ or Chanukah /xanuka/. /x/ is also used in South African English. In some dialects such as Scouse (Liverpool) either [x] or the affricate [kx] may be used as an allophone of /k/ in words such as docker [dɒkxə]. Most native speakers have a great deal of trouble pronouncing it correctly when learning a foreign language. Most speakers use the sounds [k] and [h] instead.

- Voiceless w [ʍ] is found in Scottish and Irish English, as well as in some varieties of American, New Zealand, and English English. In most other dialects it is merged with /w/, in some dialects of Scots it is merged with /f/.

Voicing and aspiration

Voicing and aspiration of stop consonants in English depend on dialect and context, but a few general rules can be given:

- Voiceless plosives and affricates (/ p/, / t/, / k/, and / tʃ/) are aspirated when they are word-initial or begin a stressed syllable – compare pin [pʰɪn] and spin [spɪn], crap [kʰɹ̥æp] and scrap [skɹæp].

- In some dialects, aspiration extends to unstressed syllables as well.

- In other dialects, such as Indian English, all voiceless stops remain unaspirated.

- Word-initial voiced plosives may be devoiced in some dialects.

- Word-terminal voiceless plosives may be unreleased or accompanied by a glottal stop in some dialects (e.g. many varieties of American English) – examples: tap [tʰæp̚], sack [sæk̚].

- Word-terminal voiced plosives may be devoiced in some dialects (e.g. some varieties of American English) – examples: sad [sæd̥], bag [bæɡ̊]. In other dialects, they are fully voiced in final position, but only partially voiced in initial position.

Supra-segmental features

Tone groups

English is an intonation language. This means that the pitch of the voice is used syntactically, for example, to convey surprise and irony, or to change a statement into a question.

In English, intonation patterns are on groups of words, which are called tone groups, tone units, intonation groups or sense groups. Tone groups are said on a single breath and, as a consequence, are of limited length, more often being on average five words long or lasting roughly two seconds. For example:

- - /duː juː niːd ˈɛnɪˌθɪŋ/ Do you need anything?

- - /aɪ dəʊnt | nəʊ/ I don't, no

- - /aɪ dəʊnt nəʊ/ I don't know (contracted to, for example, - /aɪ dəʊnəʊ/ or /aɪ dənəʊ/ I dunno in fast or colloquial speech that de-emphasises the pause between don't and know even further)

Characteristics of intonation

English is a strongly stressed language, in that certain syllables, both within words and within phrases, get a relative prominence/loudness during pronunciation while the others do not. The former kind of syllables are said to be accentuated/stressed and the latter are unaccentuated/unstressed.

Hence in a sentence, each tone group can be subdivided into syllables, which can either be stressed (strong) or unstressed (weak). The stressed syllable is called the nuclear syllable. For example:

- That | was | the | best | thing | you | could | have | done!

Here, all syllables are unstressed, except the syllables/words best and done, which are stressed. Best is stressed harder and, therefore, is the nuclear syllable.

The nuclear syllable carries the main point the speaker wishes to make. For example:

- John had not stolen that money. (... Someone else had.)

- John had not stolen that money. (... Someone said he had. or ... Not at that time, but later he did.)

- John had not stolen that money. (... He acquired the money by some other means.)

- John had not stolen that money. (... He had stolen some other money.)

- John had not stolen that money. (... He had stolen something else.)

Also

- I did not tell her that. (... Someone else told her)

- I did not tell her that. (... You said I did. or ... but now I will)

- I did not tell her that. (... I did not say it; she could have inferred it, etc)

- I did not tell her that. (... I told someone else)

- I did not tell her that. (... I told her something else)

This can also be used to express emotion:

- Oh, really? (...I did not know that)

- Oh, really? (...I disbelieve you. or ... That is blatantly obvious)

The nuclear syllable is spoken more loudly than the others and has a characteristic change of pitch. The changes of pitch most commonly encountered in English are the rising pitch and the falling pitch, although the fall-rising pitch and/or the rise-falling pitch are sometimes used. In this opposition between falling and rising pitch, which plays a larger role in English than in most other languages, falling pitch conveys certainty and rising pitch uncertainty. This can have a crucial impact on meaning, specifically in relation to polarity, the positive–negative opposition; thus, falling pitch means, "polarity known", while rising pitch means "polarity unknown". This underlies the rising pitch of yes/no questions. For example:

- When do you want to be paid?

- Now? (Rising pitch. In this case, it denotes a question: "Can I be paid now?" or "Do you desire to pay now?")

- Now. (Falling pitch. In this case, it denotes a statement: "I choose to be paid now.")

Grammar

English grammar has minimal inflection compared with most other Indo-European languages. For example, Modern English, unlike Modern German or Dutch and the Romance languages, lacks grammatical gender and adjectival agreement. Case marking has almost disappeared from the language and mainly survives in pronouns. The patterning of strong (e.g. speak/spoke/spoken) versus weak verbs inherited from its Germanic origins has declined in importance in modern English, and the remnants of inflection (such as plural marking) have become more regular.

At the same time, the language has become more analytic, and has developed features such as modal verbs and word order as resources for conveying meaning. Auxiliary verbs mark constructions such as questions, negative polarity, the passive voice and progressive aspect.

Vocabulary

The English vocabulary has changed considerably over the centuries.[43]

Like many languages deriving from Proto-Indo-European (PIE), many of the most common words in English can trace back their origin (through the Germanic branch) to PIE. Such words include the basic pronouns I, from Old English ic, (cf. Latin ego, Greek ego, Sanskrit aham), me (cf. Latin me, Greek eme, Sanskrit mam), numbers (e.g. one, two, three, cf. Latin unus, duo, tres, Greek oinos "ace (on dice)", duo, treis), common family relationships such as mother, father, brother, sister etc (cf. Greek "meter", Latin "mater", Sanskrit "matṛ"; mother), names of many animals (cf. Sankrit mus, Greek mys, Latin mus; mouse), and many common verbs (cf. Greek gignōmi, Latin gnoscere, Hittite kanes; to know).

Germanic words (generally words of Old English or to a lesser extent Norse origin) tend to be shorter than the Latinate words of English and more common in ordinary speech. This includes nearly all the basic pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, modal verbs etc. that form the basis of English syntax and grammar. The longer Latinate words are often regarded as more elegant or educated. However, the excessive use of Latinate words is considered at times to be either pretentious or an attempt to obfuscate an issue. George Orwell's essay "Politics and the English Language", considered an important scrutinization of the English language, is critical of this, as well as other perceived misuse of the language.

An English speaker is in many cases able to choose between Germanic and Latinate synonyms: come or arrive; sight or vision; freedom or liberty. In some cases, there is a choice between a Germanic derived word (oversee), a Latin derived word (supervise), and a French word derived from the same Latin word (survey). Such synonyms harbor a variety of different meanings and nuances, enabling the speaker to express fine variations or shades of thought. Familiarity with the etymology of groups of synonyms can give English speakers greater control over their linguistic register. See: List of Germanic and Latinate equivalents in English.

An exception to this and a peculiarity perhaps unique to English is that the nouns for meats are commonly different from, and unrelated to, those for the animals from which they are produced, the animal commonly having a Germanic name and the meat having a French-derived one. Examples include: deer and venison; cow and beef; swine/pig and pork, or sheep and mutton. This is assumed to be a result of the aftermath of the Norman invasion, where a French-speaking elite were the consumers of the meat, produced by Anglo-Saxon lower classes.

Since the majority of words used in informal settings will normally be Germanic, such words are often the preferred choices when a speaker wishes to make a point in an argument in a very direct way. A majority of Latinate words (or at least a majority of content words) will normally be used in more formal speech and writing, such as a courtroom or an encyclopedia article. However, there are other Latinate words that are used normally in everyday speech and do not sound formal; these are mainly words for concepts that no longer have Germanic words, and are generally assimilated better and in many cases do not appear Latinate. For instance, the words mountain, valley, river, aunt, uncle, move, use, push and stay are all Latinate.

English easily accepts technical terms into common usage and often imports new words and phrases. Examples of this phenomenon include: cookie, Internet and URL (technical terms), as well as genre, über, lingua franca and amigo (imported words/phrases from French, German, modern Latin, and Spanish, respectively). In addition, slang often provides new meanings for old words and phrases. In fact, this fluidity is so pronounced that a distinction often needs to be made between formal forms of English and contemporary usage.

See also: sociolinguistics.

Number of words in English

The General Explanations at the beginning of the Oxford English Dictionary states:

| “ | The Vocabulary of a widely diffused and highly cultivated living language is not a fixed quantity circumscribed by definite limits... there is absolutely no defining line in any direction: the circle of the English language has a well-defined centre but no discernible circumference. | ” |

The vocabulary of English is undoubtedly vast, but assigning a specific number to its size is more a matter of definition than of calculation. Unlike other languages, such as French, German, Spanish and Italian there is no Academy to define officially accepted words and spellings. Neologisms are coined regularly in medicine, science and technology and other fields, and new slang is constantly developed. Some of these new words enter wide usage; others remain restricted to small circles. Foreign words used in immigrant communities often make their way into wider English usage. Archaic, dialectal, and regional words might or might not be widely considered as "English".

The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition (OED2) includes over 600,000 definitions, following a rather inclusive policy:

| “ | It embraces not only the standard language of literature and conversation, whether current at the moment, or obsolete, or archaic, but also the main technical vocabulary, and a large measure of dialectal usage and slang (Supplement to the OED, 1933).[44] | ” |

The editors of Webster's Third New International Dictionary, Unabridged (475,000 main headwords) in their preface, estimate the number to be much higher. It is estimated that about 25,000 words are added to the language each year.[45]

Word origins

One of the consequences of the French influence is that the vocabulary of English is, to a certain extent, divided between those words which are Germanic (mostly West Germanic, with a smaller influence from the North Germanic branch) and those which are "Latinate" (Latin-derived, either directly or from Norman French or other Romance languages).

Numerous sets of statistics have been proposed to demonstrate the origins of English vocabulary. None, as of yet, is considered definitive by most linguists.

A computerised survey of about 80,000 words in the old Shorter Oxford Dictionary (3rd ed.) was published in Ordered Profusion by Thomas Finkenstaedt and Dieter Wolff (1973)[46] that estimated the origin of English words as follows:

- Langue d'oïl, including French and Old Norman: 28.3%

- Latin, including modern scientific and technical Latin: 28.24%

- Other Germanic languages (including words directly inherited from Old English): 25%

- Greek: 5.32%

- No etymology given: 4.03%

- Derived from proper names: 3.28%

- All other languages contributed less than 1%

A survey by Joseph M. Williams in Origins of the English Language of 10,000 words taken from several thousand business letters gave this set of statistics:[47]

- French (langue d'oïl): 41%

- "Native" English: 33%

- Latin: 15%

- Danish: 2%

- Dutch: 1%

- Other: 10%

However, 83% of the 1,000 most-common, and all of the 100 most-common English words are Germanic.[48]

Dutch origins

Words describing the navy, types of ships, and other objects or activities on the water are often from Dutch origin. Yacht (jacht) and cruiser (kruiser) are examples.

French origins

There are many words of French origin in English, such as competition, art, table, publicity, police, role, routine, machine, force, and many others that have been and are being anglicised; they are now pronounced according to English rules of phonology, rather than French. A large portion of English vocabulary is of French or Langues d'oïl origin, most derived from, or transmitted via, the Anglo-Norman spoken by the upper classes in England for several hundred years after the Norman conquest of England.

Idiomatic

The multiple origins of words used in English, and the willingness of English speakers to innovate and be creative, has resulted in many expressions that seem somewhat odd to newcomers to the language, but which can convey complex meanings in sometimes-colorful ways.

Consider, for example, the common idiom of using the same word to mean an activity and those engaged in that activity, and sometimes also a verb. Here are a few examples:

| Activity | Actor(s) | Verb |

|---|---|---|

| aggregation | aggregation | aggregate |

| assembly | assembly | assemble |

| congregation | congregation | congregate |

| court | court | court |

| delegation | delegation | delegate |

| hospital | hospital | (none) |

| gathering | gathering | gather |

| hunt | hunt | hunt |

| march | march | march |

| militia | militia | (none) |

| ministry | ministry | minister |

| movement | movement | move |

| muster | muster | muster |

| police | police | police |

| service | service | serve |

| university | university | (none) |

| viking | viking | vik (archaic) |

| wedding | wedding | wed |

Writing system

English has been written using the Latin alphabet since around the ninth century. (Before that, Old English had been written using Anglo-Saxon runes.) The spelling system, or orthography, is multilayered, with elements of French, Latin and Greek spelling on top of the native Germanic system; it has grown to vary significantly from the phonology of the language. The spelling of words often diverges considerably from how they are spoken.

Though letters and sounds may not correspond in isolation, spelling rules that take into account syllable structure, phonetics, and accents are 75% or more reliable.[49] Some phonics spelling advocates claim that English is more than 80% phonetic.[50]

In general, the English language, being the product of many other languages and having only been codified orthographically in the 16th century, has fewer consistent relationships between sounds and letters than many other languages. The consequence of this orthographic history is that reading can be challenging.[51] It takes longer for students to become completely fluent readers of English than of many other languages, including French, Greek, and Spanish.[52]

Basic sound-letter correspondence

- See also: Hard and soft C and Hard and soft G

Only the consonant letters are pronounced in a relatively regular way:

| IPA | Alphabetic representation | Dialect-specific |

|---|---|---|

| p | p | |

| b | b | |

| t | t, th (rarely) thyme, Thames | th thing (African American, New York) |

| d | d | th that (African American, New York) |

| k | c (+ a, o, u, consonants), k, ck, ch, qu (rarely) conquer, kh (in foreign words) | |

| g | g, gh, gu (+ a, e, i), gue (final position) | |

| m | m | |

| n | n | |

| ŋ | n (before g or k), ng | |

| f | f, ph, gh (final, infrequent) laugh, rough | th thing (many forms of English language in England) |

| v | v | th with (Cockney, Estuary English) |

| θ | th thick, think, through | |

| ð | th that, this, the | |

| s | s, c (+ e, i, y), sc (+ e, i, y), ç (façade) | |

| z | z, s (finally or occasionally medially), ss (rarely) possess, dessert, word-initial x xylophone | |

| ʃ | sh, sch, ti (before vowel) portion, ci/ce (before vowel) suspicion, ocean; si/ssi (before vowel) tension, mission; ch (esp. in words of French origin); rarely s/ss before u sugar, issue; chsi in fuchsia only | |

| ʒ | medial si (before vowel) division, medial s (before "ur") pleasure, zh (in foreign words), z before u azure, g (in words of French origin) (+e, i, y) genre | |

| x | kh, ch, h (in foreign words) | occasionally ch loch (Scottish English, Welsh English) |

| h | h (syllable-initially, otherwise silent) | |

| tʃ | ch, tch, t before u future, culture | t (+ u, ue, eu) tune, Tuesday, Teutonic (several dialects - see Phonological history of English consonant clusters) |

| dʒ | j, g (+ e, i, y), dg (+ e, i, consonant) badge, judg(e)ment | d (+ u, ue, ew) dune, due, dew (several dialects - another example of yod coalescence) |

| ɹ | r, wr (initial) wrangle | |

| j | y (initially or surrounded by vowels) | |

| l | l | |

| w | w | |

| ʍ | wh (pronounced hw) | Scottish and Irish English, as well as some varieties of American, New Zealand, and English English |

Written accents

Unlike most other Germanic languages, English has almost no diacritics except in foreign loanwords (like the acute accent in café), and in the uncommon use of a diaeresis mark (often in formal writing) to indicate that two vowels are pronounced separately, rather than as one sound (e.g. naïve, Zoë). It may be acceptable to leave out the marks, depending on the target audience, or the context in which the word is used.

Some English words retain the diacritic to distinguish them from others, such as animé, exposé, lamé, öre, øre, pâté, piqué, and rosé, though these are sometimes also dropped (résumé/resumé is usually spelled resume in the United States). There are loan words which occasionally use a diacritic to represent their pronunciation that is not in the original word, such as maté, from Spanish yerba mate, following the French usage, but they are extremely rare.

Formal written English

A version of the language almost universally agreed upon by educated English speakers around the world is called formal written English. It takes virtually the same form no matter where in the English-speaking world it is written. In spoken English, by contrast, there are a vast number of differences between dialects, accents, and varieties of slang, colloquial and regional expressions. In spite of this, local variations in the formal written version of the language are quite limited, being restricted largely to the spelling differences between British and American English.

Basic and simplified versions

To make English easier to read, there are some simplified versions of the language. One basic version is named Basic English, a constructed language with a small number of words created by Charles Kay Ogden and described in his book Basic English: A General Introduction with Rules and Grammar (1930). The language is based on a simplified version of English. Ogden said that it would take seven years to learn English, seven months for Esperanto, and seven weeks for Basic English, comparable with Ido. Thus companies who need to make complex books for international use employ Basic English, and by language schools that need to give people some knowledge of English in a short time.

Ogden did not put any words into Basic English that could be said with a few other words and he worked to make the words work for speakers of any other language. He put his set of words through a large number of tests and adjustments. He also made the grammar simpler, but tried to keep the grammar normal for English users.

The concept gained its greatest publicity just after the Second World War as a tool for world peace. Although it was not built into a program, similar simplifications were devised for various international uses.

Another version, Simplified English, exists, which is a controlled language originally developed for aerospace industry maintenance manuals. It offers a carefully limited and standardised subset of English. Simplified English has a lexicon of approved words and those words can only be used in certain ways. For example, the word close can be used in the phrase "Close the door" but not "do not go close to the landing gear".

See also

- Changes to Old English vocabulary

- English for Academic Purposes

- English language learning and teaching

- Language Report

- Teaching English as a foreign language

Notes

- ↑ "English, a. and n." The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. OED Online. Oxford University Press. 6 September 2007 http://dictionary.oed.com/cgi/entry/50075365

- ↑ see: Ethnologue (1984 estimate); The Triumph of English, The Economist, Dec. 20, 2001; Ethnologue (1999 estimate); "20,000 Teaching Jobs" (in English). Oxford Seminars. Retrieved on 2007-02-18.;

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Lecture 7: World-Wide English". EHistLing. Retrieved on 2007-03-26.

- ↑ Ethnologue, 1999

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Languages of the World (Charts), Comrie (1998), Weber (1997), and the Summer Institute for Linguistics (SIL) 1999 Ethnologue Survey. Available at The World's Most Widely Spoken Languages

- ↑ "Global English: gift or curse?". Retrieved on 2005-04-04.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 David Graddol (1997). "The Future of English?". The British Council. Retrieved on 2007-04-15.

- ↑ "The triumph of English". The Economist (2001-12-20). Retrieved on 2007-03-26.

- ↑ "Lecture 7: World-Wide English". EHistLing. Retrieved on 2007-03-26.

- ↑ Anglik English language resource

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Linguistics research center Texas University,

- ↑ The Germanic Invasions of Western Europe, Calgary University

- ↑ English Language Expert

- ↑ History of English, Chapter 5 "From Old to Middle English"

- ↑ Curtis, Andy. Color, Race, And English Language Teaching: Shades of Meaning. 2006, page 192.

- ↑ Ethnologue, 1999

- ↑ CIA World Factbook, Field Listing - Languages (World).

- ↑ Mair, Victor H. (1991). "What Is a Chinese "Dialect/Topolect"? Reflections on Some Key Sino-English Linguistic Terms". Sino-Platonic Papers. http://sino-platonic.org/complete/spp029_chinese_dialect.pdf.

- ↑ "English language". Columbia University Press (2005). Retrieved on 2007-03-26.

- ↑ 20,000 Teaching

- ↑ Not the Queen's English, Newsweek International, 7 March edition, 2007.

- ↑ "U.S. Census Bureau, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2003, Section 1 Population" (pdf) (in English) 59 pages. U.S. Census Bureau. Table 47 gives the figure of 214,809,000 for those five years old and over who speak exclusively English at home. Based on the American Community Survey, these results exclude those living communally (such as college dormitories, institutions, and group homes), and by definition exclude native English speakers who speak more than one language at home.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language, Second Edition, Crystal, David; Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, [1995 (2003-08-03).]

- ↑ Population by mother tongue and age groups, 2006 counts, for Canada, provinces and territories – 20% sample data, Census 2006, Statistics Canada.

- ↑ Census Data from Australian Bureau of Statistics Main Language Spoken at Home. The figure is the number of people who only speak English at home.

- ↑ Census in Brief, page 15 (Table 2.5), 2001 Census, Statistics South Africa.

- ↑ Languages spoken, 2006 Census, Statistics New Zealand. No figure is given for the number of native speakers, but it would be somewhere between the number of people who spoke English only (3,008,058) and the total number of English speakers (3,673,623), if one ignores the 197,187 people who did not provide a usable answer.

- ↑ Subcontinent Raises Its Voice, Crystal, David; Guardian Weekly: Friday 19 November 2004.

- ↑ Yong Zhao; Keith P. Campbell (1995). "English in China". World Englishes 14 (3): 377–390. Hong Kong contributes an additional 2.5 million speakers (1996 by-census]).

- ↑ Census of India's Indian Census, Issue 10, 2003, pp 8-10, (Feature: Languages of West Bengal in Census and Surveys, Bilingualism and Trilingualism).

- ↑ Tropf, Herbert S. 2004. India and its Languages. Siemens AG, Munich

- ↑ For the distinction between "English Speakers," and "English Users," please see: TESOL-India (Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages)], India: World's Second Largest English-Speaking Country. Their article explains the difference between the 350 million number mentioned in a previous version of this Wikipedia article and a more plausible 90 million number:

“ "Wikipedia's India estimate of 350 million includes two categories - "English Speakers" and "English Users". The distinction between the Speakers and Users is that Users only know how to read English words while Speakers know how to read English, understand spoken English as well as form their own sentences to converse in English. The distinction becomes clear when you consider the China numbers. China has over 200~350 million users that can read English words but, as anyone can see on the streets of China, only handful of million who are English speakers." ” - ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics

- ↑ Nancy Morris (1995), Puerto Rico: Culture, Politics, and Identity, Praeger/Greenwood, pp. 62, ISBN 0275952282, http://books.google.com/books?id=vyQDYqz2kFsC&pg=RA1-PA62&lpg=RA1-PA62&dq=%22puerto+rico%22+official+language+1993&source=web&ots=AZKLran6u3&sig=8fkQ9gwM0B0kwVYMNtXr-_9dnro

- ↑ Languages Spoken in the U.S., National Virtual Translation Center, 2006.

- ↑ U.S. English Foundation, Official Language Research – United Kingdom.

- ↑ U.S. ENGLISH,Inc

- ↑ Multilingualism in Israel, Language Policy Research Center

- ↑ The Official EU languages

- ↑ European Union

- ↑ Cox, Felicity (2006). "Australian English Pronunciation into the 21st century". Prospect 21: 3–21. http://www.shlrc.mq.edu.au/~felicity/Papers/Prospect_Erratum_v1.pdf. Retrieved on 2007-07-22.

- ↑ For the processes and triggers of English vocabulary changes cf. English and General Historical Lexicology (by Joachim Grzega and Marion Schöner)

- ↑ It went on to clarify,

“ Hence we exclude all words that had become obsolete by 1150 [the end of the Old English era] . . . Dialectal words and forms which occur since 1500 are not admitted, except when they continue the history of the word or sense once in general use, illustrate the history of a word, or have themselves a certain literary currency. ” - ↑ Kister, Ken. "Dictionaries defined." Library Journal, 6/15/92, Vol. 117 Issue 11, p43, 4p, 2bw

- ↑ Finkenstaedt, Thomas; Dieter Wolff (1973). Ordered profusion; studies in dictionaries and the English lexicon. C. Winter. ISBN 3-533-02253-6.

- ↑ Joseph M. Willams, Origins of the English Language at Amazon.com

- ↑ Old English Online

- ↑ Abbott, M. (2000). Identifying reliable generalizations for spelling words: The importance of multilevel analysis. The Elementary School Journal 101(2), 233-245.

- ↑ Moats, L. M. (2001). Speech to print: Language essentials for teachers. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Company.

- ↑ Diane McGuinness, Why Our Children Can’t Read (New York: Touchstone, 1997) pp. 156-169

- ↑ Ziegler, J. C., & Goswami, U. (2005). Reading acquisition, developmental dyslexia, and skilled reading across languages. Psychological Bulletin, 131(1), 3-29.

References

- Baugh, Albert C.; Thomas Cable (2002). A history of the English language (5th ed. ed.). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-28099-0.

- Bragg, Melvyn (2004). The Adventure of English: The Biography of a Language. Arcade Publishing. ISBN 1-55970-710-0.

- Crystal, David (1997). English as a Global Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-53032-6.

- Crystal, David (2004). The Stories of English. Allen Lane. ISBN 0-7139-9752-4.

- Crystal, David (2003). The Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language (2nd ed. ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-53033-4.

- Halliday, MAK (1994). An introduction to functional grammar (2nd ed. ed.). London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 0-340-55782-6.

- Hayford, Harrison; Howard P. Vincent (1954). Reader and Writer. Houghton Mifflin Company. [2]

- McArthur, T. (ed.) (1992). The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-214183-X.

- Robinson, Orrin (1992). Old English and Its Closest Relatives. Stanford Univ. Press. ISBN 0-8047-2221-8.

- Kenyon, John Samuel and Knott, Thomas Albert, A Pronouncing Dictionary of American English, G & C Merriam Company, Springfield, Mass, USA,1953.

External links

- English language at Ethnologue

- National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition

- Accents of English from Around the World Hear and compare how the same 110 words are pronounced in 50 English accents from around the world - instantaneous playback online

- The Global English Survey Project A survey tracking how non-native speakers around the world use English

- 6000 English words recorded by a native speaker

- More than 20000 English words recorded by a native speaker

Dictionaries

- Merriam-Webster's online dictionary

- Oxford's online dictionary

- dict.org

- English language word roots, prefixes and suffixes (affixes) dictionary

- Collection of English bilingual dictionaries

- Dictionary of American Regional English

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||