Encyclopédie

| Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers | |

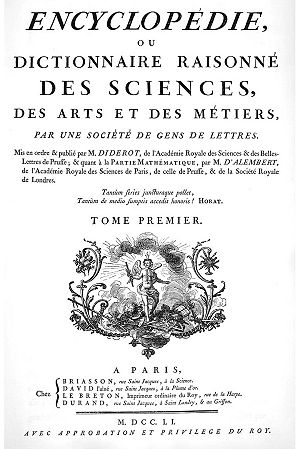

The title page of the Encyclopédie |

|

| Author | Numerous contributors, edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert |

|---|---|

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Subject(s) | General |

| Genre(s) | Reference encyclopedia |

| Publisher | André Le Breton, Michel-Antoine David, Laurent Durand, and Antoine-Claude Briasson |

| Publication date | 1751-72 |

Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (English: Encyclopedia, or a systematic dictionary of the sciences, arts, and crafts) was a general encyclopedia published in France between 1751 and 1772, with later supplements and revisions in 1772, 1777 and 1780 and numerous foreign editions and later derivatives.

Its introduction, the Preliminary Discourse, is considered an important exposition of Enlightenment ideals. The Encyclopédie's self-professed aim was "to change the way people think." It was hoped that the work would eventually encompass all of human knowledge; Denis Diderot explained the goal of the project as "All things must be examined, debated, investigated without exception and without regard for anyone's feelings."[1]

Contents |

Origins

The Encyclopédie was originally meant to be simply a French translation of Ephraim Chambers's Cyclopaedia (1728).[2] The translation was commissioned by Paris book publisher André Le Breton in 1743 to John Mills, an English resident in France. In May 1745 Le Breton announced the work as available for sale - however to Le Breton's dismay, Mills had not done the work he was commissioned to do; in fact, he could barely read and write French and did not even own a copy of Cyclopaedia. Le Breton had been swindled, and so he physically beat Mills with a cane—Mills sued on assault charges, but Le Breton was acquitted in court as being justified.[3] Setting out to find a new editor, Le Breton engaged Jean Paul de Gua de Malves. Among those hired by Malves were the young Étienne Bonnot de Condillac, Jean le Rond d'Alembert and Denis Diderot. Within thirteen months in August 1747 Malves was fired due to his rigid methods, and Le Breton hired Denis Diderot and Jean d'Alembert as the new editors. Diderot would remain editor for the next 25 years seeing the Encyclopédie through to completion.

Publication

The work comprised 35 volumes, with 71,818 articles, and 3,129 illustrations. The first 28 volumes were published between 1751 and 1766 and were edited by Diderot - although some of the later picture-only volumes were not actually printed until 1772. The remaining five volumes were completed by other editors in 1777, along with a two volume index in 1780. Many of the most noted figures of the French enlightenment contributed to the work including Voltaire, Rousseau, and Montesquieu.[4] The single greatest contributor was Louis de Jaucourt who wrote 17,266 articles, or about 8 per day between 1759 and 1765.

The writers of the encyclopedia saw it as a vehicle to covertly destroy superstitions while overtly providing access to human knowledge. It was a summary of thought and belief of the Enlightenment. In ancien régime France it caused a storm of controversy, due mostly to its tone of religious tolerance. The encyclopedia praised Protestant thinkers and challenged Catholic dogma, and classified religion as a branch of philosophy, not as the ultimate source of knowledge and moral advice. The entire work was banned by royal decree and officially closed down after the first seven volumes in 1759;[5] but because it had many highly placed supporters, notably Madame de Pompadour, work continued "in secret". In truth, secular authorities did not want to disrupt the commercial enterprise which employed hundreds of people. To appease the church's enemies of the project, the authorities had officially banned the enterprise, but they turned a blind eye to its continued existence.

It was also a vast compendium of the technologies of the period, describing the traditional craft tools and processes. Much information was taken from the Descriptions des Arts et Métiers.

In 1750 the full title was Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, par une société de gens de lettres, mis en ordre par M. Diderot de l'Académie des Sciences et Belles-Lettres de Prusse, et quant à la partie mathématique, par M. d'Alembert de l'Académie royale des Sciences de Paris, de celle de Prusse et de la Société royale de Londres. The title-page was amended as d'Alembert acquired more titles.

In 1775, Charles Joseph Panckoucke obtained the rights to reissue the work. He issued five volumes of supplementary material and a two volume index from 1776 to 1780. Some include these seven volumes as part of the first full issue of the Encyclopédie, for a total of 35 volumes, although they were not written or edited by the original famed authors.

From 1782 to 1832, Panckoucke and his successors published an expanded edition of the work in 166 volumes as the Encyclopédie méthodique. That work, enormous for the time, occupied a thousand workers in production and 2,250 contributors.

The Encyclopédie presented a taxonomy of human knowledge (See fig.3) which was inspired by Francis Bacon's Advancement of Knowledge. The three main branches of knowledge are: "Memory"/History, "Reason"/Philosophy, and "Imagination"/Poetry. Notable is the fact that theology is ordered under 'Philosophy'. Robert Darnton argues that this categorisation of religion as being subject to human reason and not a source of knowledge in and of itself, was a significant factor in the controversy surrounding the work. Additionally, notice that 'Knowledge of God' is only a few nodes away from 'Divination' and 'Black Magic'.

Influence

The Encyclopédie played an important role in the intellectual ferment leading to the French Revolution. "No encyclopaedia perhaps has been of such political importance, or has occupied so conspicuous a place in the civil and literary history of its century. It sought not only to give information, but to guide opinion," wrote the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. In The Encyclopédie and the Age of Revolution, a work published in conjunction with a 1989 exhibition of the Encyclopédie at the University of California, Los Angeles, Clorinda Donato writes the following:

The encyclopedians successfully argued and marketed their belief in the potential of reason and unified knowledge to empower human will and thus helped to shape the social issues that the French Revolution would address. Although it is doubtful whether the many artisans, technicians, or laborers whose work and presence and interspersed throughout the Encyclopédie actually read it, the recognition of their work as equal to that of intellectuals, clerics, and rulers prepared the terrain for demands for increased representation. Thus the Encyclopédie served to recognize and galvanize a new power base, ultimately contributing to the destruction of old values and the creation of new ones (12).

But note Frank Kafker, who explains that the Encyclopedists were not a unified group[6]

despite their reputation, [the Encyclopedists] were not a close-knit group of radicals intent on subverting the Old Regime in France. Instead they were a disparate group of men of letters, physicians, scientists, craftsmen and scholars ... Even the small minority who were persecuted for writing articles belittling what they viewed as unreasonable customs—thus weakening the might of the Catholic Church and undermining that of the monarchy—did not envision that their ideas would encourage a revolution.

While it is debatable that the editors intended to have a radical influence on French society, it can hardly be denied that it did. The Encyclopédie denied that the teachings of the Catholic Church could be treated as authoritative in matters of science. The editors also refused to treat the decisions of political powers as definitive in intellectual or artistic questions. Given that Paris was the intellectual capital of Europe at the time and that many European leaders used French as their administrative language, these ideas had the capacity to spread.[7]

The Encyclopédie today survives through modern encyclopedias, including the free one known as wikipedia.

Contributors

Notable contributors to the Encyclopédie including their area of contribution (for a more detailed list, see French Encyclopédistes):

- Jean le Rond d'Alembert — editor; science (esp. mathematics), contemporary affairs, philosophy, religion, among others

- André Le Breton — chief publisher; printer's ink article

- Étienne Bonnot de Condillac — philosophy

- Daubenton — natural history

- Denis Diderot — chief editor; economics, mechanical arts, philosophy, politics, religion, among others

- Baron d'Holbach — science (chemistry, mineralogy), politics, religion, among others

- Chevalier Louis de Jaucourt — economics, literature, medicine, politics, among others

- Montesquieu — part of the "goût" article (English: concept of taste)

- François Quesnay — Farmers and Grains article

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau — music, political theory

- Anne Robert Jacques Turgot, Baron de Laune — economics, etymology, philosophy, physics

- Voltaire — history, literature, philosophy

Statistics

Approximate size of the Encyclopédie:

- 17 volumes of articles, issued from 1751 to 1765

- 11 volumes of illustrations, issued from 1762 to 1772

- 18,000 pages of text

- 75,000 entries

- 44,000 main articles

- 28,000 secondary articles

- 2,500 illustration indices

- 20,000,000 words in total

Print run: 4,250 copies (note: even single-volume works in the 18th Century seldom had a print run of more than 1,500 copies)

Quotes

- "Reason is to the philosopher what grace is to the Christian... Other men walk in darkness; the philosopher, who has the same passions, acts only after reflection; he walks through the night, but it is preceded by a torch. The philosopher forms his principles on an infinity of particular observations. He does not confuse truth with plausibility; he takes for truth what is true, for forgery what is false, for doubtful what is doubtful, and probable what is probable. The philosophical spirit is thus a spirit of observation and accuracy." (Philosophers article, Dumarsais)

- "If exclusive privileges were not granted, and if the financial system would not tend to concentrate wealth, there would be few great fortunes and no quick wealth. When the means of growing rich is divided between a greater number of citizens, wealth will also be more evenly distributed; extreme poverty and extreme wealth would be also rare." (Wealth article, Diderot)

Literature

- Preliminary discourse to the Encyclopedia of Diderot, Jean Le Rond d'Alembert, translated by Richard N. Schwab, 1995. ISBN 0-226-13476-8

- Jean d'Alembert by Ronald Grimsley. (1963)

- The Business of Enlightenment: A Publishing History of the Encyclopédie, 1775-1800 by Robert Darnton (1979) ISBN 0674087852

- The Encyclopedists as individuals: a biographical dictionary of the authors of the Encyclopédie by Frank A. Kafker and Serena L. Kafker. Published 1988 in the Studies of Voltaire and the eighteenth century. ISBN 0-7294-0368-8

- Encyclopédie ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, Editions Flammarion, 1993. ISBN 2-080704265

- Diderot, the Mechanical Arts, and the Encyclopédie, John R. Pannabecker, 1994. With bibliography.

- L'Encyclopédie de Diderot et d'Alembert, édition DVD, Redon, ASIN: B0000DBA4X -- the complete Encyclopédie on DVD-ROM

- Enlightening the World: Encyclopedie, The Book That Changed the Course of History by Philipp Blom (2005). ISBN 1403968950

- The Encylopédie and the Age of Revolution. Ed. Clorinda Donato and Robert M. Maniquis. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1992. ISBN 0-8161-0527-8

Facsimiles

Readex Microprint Corporation, NY 1969. 5 vol The full text and images reduced to 4 double-spread pages of the original appearing on one folio-sized page of this printing.

Later released by the Pergamon Press, NY and Paris with ISBN 0080901050

References

- ↑ Denis Diderot as quoted in Lynn Hunt, R. Po-chia Hsia, Thomas R. Martin, Barbara H. Rosenwein, and Bonnie G. Smith, The Making of the West: Peoples and Cultures: A Concise History: Volume II: Since 1340, Second Edition (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2007), 611.

- ↑ Bryan Magee. The Story of Philosophy. DK Publishing, Inc., New York: 1998. page 124

- ↑ Philipp Blom (2005). Enlightening the World. pp. 35-37

- ↑ Bryan Magee. The Story of Philosophy. DK Publishing, Inc., New York: 1998. page 124

- ↑ Bryan Magee. The Story of Philosophy. DK Publishing, Inc., New York: 1998. page 125

- ↑ The Camargo Foundation : Fellow Project Details

- ↑ Bryan Magee. The Story of Philosophy. DK Publishing, Inc., New York: 1998. page 125

External links

- On-line version in original French

- On-line version with an English interface and the dates of publication

- Encyclopédie collaborative translation project, currently contains a rather small but growing collection of articles translated into English (570 articles as of September 18, 2008).

- The Encyclopedie, discussion on the BBC Radio 4 programme In Our Time, broadcast on 26 October 2006. With Judith Hawley, Senior Lecturer in English at Royal Holloway, University of London, Caroline Warman, Fellow and Tutor in French at Jesus College, Oxford, David Wootton, Anniversary Professor of History at the University of York, and presented by Melvyn Bragg.

- Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers on French Wikisource