Emiliano Zapata

| Emiliano Zapata Salazar | |

|---|---|

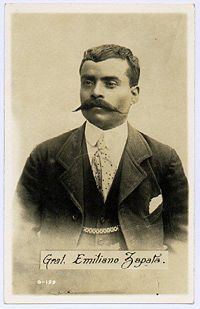

General Emiliano Zapata. |

|

| Date of birth: | August 8, 1879 |

| Place of birth: | Anenecuilco, Morelos, Mexico |

| Date of death: | April 10, 1919 (aged 39) |

| Place of death: | Chinameca, Morelos, Mexico |

| Major organizations: | Liberation Army of the South |

Emiliano Zapata Salazar (August 8, 1879–April 10, 1919) was a leading figure in the Mexican Revolution, which broke out in 1910, and which was initially directed against the president Porfirio Díaz. He formed and commanded an important revolutionary force, the Liberation Army of the South.

Contents |

Biography

A symbol of the agrarian reform movement, Zapata was born to Gabriel Zapata a peasant who trained and sold horses, and Cleofas Salazar in the small central state of Morelos, in the village of Anenecuilco (modern-day Ayala municipality). Zapata's family were Mestizos, having mainly Nahua ancestry with some Spanish admixture;[1] Emiliano was the ninth out of ten children. Emiliano, a peasant since childhood, gained insight into the severe difficulties of the countryside.[2] He received a limited education from his teacher, Emilio Vara. He had to care for his family because his father died when Zapata was 17. Around the turn of the 20th century Anenecuilco was an indigenous Nahuatl speaking community, and although Zapata is generally thought to have been a mestizo there exist eyewitness accounts stating that Emiliano Zapata spoke Nahuatl fluently.[3]

At that time, Mexico was ruled by a dictatorship under Porfirio Díaz, who had seized power in 1876. The social system of the time was a sort of proto-capitalist feudal system, with large landed estates (haciendas) controlling more and more of the land and squeezing out the independent communities of the indigenous and mestizos, who were then subsequently forced into debt slavery (peonaje) on the haciendas. Díaz ran local elections to pacify the people and run a government that they could argue was self-imposed. Under Díaz, close confidantes and associates were given offices in districts throughout Mexico. These offices became the enforcers of "land reforms" that actually concentrated the haciendas into fewer hands.

Zapata's family, although not wealthy, still retained its independence. Like most of the families in Anenecuilco, they were always in danger of poverty, although avoiding peonage and maintaining their own land (rancho). In fact, the family had in previous generations been porfirista, that is, supporters of Díaz. Zapata himself always had a reputation for being a fancy dresser, appearing at bullfights and rodeos in his elaborate charro (cowboy) outfit. In 1906, he attended a meeting in Cuautla, where they discussed a way to defend the land of the people which on several occasions he had worked as a farmhand. Due to his first acts of rebelliousness, he was enrolled in the Ninth Regiment in 1908 and sent to Cuernavaca. However, because of his talent with horses, he remained a soldier for only six months and left for Mexico City at the request of Ignacio de la Torre, who employed him as a groom.[4] Though his flashiness would usually have associated him with the rich hacendados who controlled the lands, he seems to have retained the admiration and even adoration of the people of his village, Anenecuilco, so that by the time he was 30, he was the head of the defense committee of the village, a post which made him the spokesman for the village's interests. He was directly elected to this position during the autumn of 1909, just a year before the start of the revolution.

Zapata became a leading figure in the village of Anenecuilco, where his family had lived for many generations, and he became involved in struggles for the rights of the campesinos of Morelos. He was able to oversee the redistribution of the land from some haciendas peacefully, but had problems with others. He observed numerous conflicts between villagers and hacendados over the constant theft of village land, and in one instance, saw the hacendados torch an entire village.

For many years, he campaigned steadfastly for the rights of the villagers, first establishing via ancient title deeds their claims to disputed land, and then pressing the recalcitrant governor of Morelos into action. Finally, disgusted with the slow response from the government and the overt bias towards the wealthy plantation owners, Zapata began making use of armed force, simply taking over the land in dispute.

The 1910 Revolution

At this time, Porfirio Díaz was being threatened by the candidacy of Francisco I. Madero. Zapata made quiet alliances with Madero, whom he perceived to be the best chance for genuine change in the country.

In 1910, Zapata quickly took an important role, becoming the general of an army that formed in Morelos – the Ejército Libertador del Sur (Liberation Army of the South).

Zapata joined Madero’s campaign against President Diaz. With the support of Pancho Villa, Pascual Orozco, Emiliano Zapata, and rebellious peasants, Madero overthrew Díaz in May of 1911 in the battle at Ciudad Juárez. A provisional government was formed under Francisco León de la Barra. Under Madero, some new land reforms were carried out and elections were to be ensured. However, Zapata was dissatisfied with Madero's stance on land reform, and was unable, despite repeated efforts, to make him understand the importance of the issue or to get him to act on it. Madero and Zapata's relations worsened during the summer of 1911 as Madero appointed a governor who supported plantation owners and refused to meet Zapata’s agrarian goals. Compromises between the two failed in November 1911, days after Madero appointed himself President, and Zapata and Montaño fled to the mountains of southwest Puebla. There they formed the most radical reform plan in Mexico; the Plan de Ayala.

Zapata was partly influenced by an anarchist from Oaxaca named Ricardo Flores Magón. The influence of Flores Magón on Zapata can be seen in the Zapatistas' Plan de Ayala, but even more noticeably in their slogan (this slogan was never used by Zapata) "Tierra y libertad" or "land and liberty", the title and maxim of Flores Magón's most famous work. Zapata's introduction to anarchism came via a local schoolteacher, Otilio Montaño Sánchez – later a general in Zapata's army, executed on 17 May 1917 – who exposed Zapata to the works of Peter Kropotkin and Flores Magón at the same time as Zapata was observing and beginning to participate in the struggles of the peasants for the land.

The plan proclaimed the Zapatista demands for "Reforma, Libertad Ley y Justicia" (Reform, Freedom, Law and justice) Zapata also declared the Maderistas as a counter-revolution and denounced Madero. Zapata mobilized his Liberation Army and allied with former Maderistas Pascual Orozco and Emiliano Vázquez Gómez. Orozco was from Chihuahua, near the U.S. border, and thus was able to aid the Zapatistas with a supply of arms.

Madero, alarmed, asked Zapata to disarm and demobilize. Zapata responded that, if the people could not win their rights now, when they were armed, they would have no chance once they were unarmed and helpless. Madero sent several generals in an attempt to deal with Zapata, but these efforts had little success.

Although government forces could never completely defeat Zapata in battle, he fell victim to a carefully staged ambush by Gen. Pablo González and his lieutenant, Col. Jesús Guajardo. Guajardo proposed González feign a defection to Zapata's forces. González agreed, and to make the defection appear sincere, he arranged for Guajardo to attack a Federal column, killing 57 soldiers. Zapata subsequently agreed to receive a messenger from Guajardo, to arrange a meeting to speak about Guajardo's defection.

On April 10, 1919, Guajardo invited Zapata to a meeting, intimating that he intended to defect to the revolutionaries. However, when Zapata arrived at the Hacienda de San Juan, in Chinameca, Ayala municipality, Guajardo's men riddled him with bullets. They then took his body to Cuautla to claim the bounty, where they are reputed to have been given only half of what was promised.

Following Zapata's death, the Liberation Army of the South slowly fell apart, although Zapata's heir apparent Gildardo Magaña and many other Zapata adherents went on to political careers as representatives of Zapatista causes and positions in the Mexican army and government. Some of his former generals like Genovevo de la O allied with Obregón while others eventually disappeared after Carranza was deposed.

Legacy

Zapata's influence lasts to this day, particularly in revolutionary tendencies in south Mexico. There are controversies on the portrayal of Emiliano Zapata and his followers, on whether they were bandits or revolutionaries. But in modern times, Zapata is one of the most revered national heroes of Mexico: to many Mexicans, specifically the peasant and indigenous citizens, Zapata was a practical revolutionary who sought the implementation of liberties and agrarian rights outlined in the Plan of Ayala. He was a realist with the goal of achieving political and economic emancipation of the peasants in southern Mexico, and leading them out of severe poverty.

Many popular organizations take their name from Zapata, most notably the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional or EZLN in Spanish), the revolutionary movement of indigenous peoples that emerged in the state of Chiapas in 1994 and is colloquially known as "the Zapatistas". Towns, streets, and housing developments called "Emiliano Zapata" are common across the country and he has, at times, been depicted on Mexican banknotes.

Modern activists in Mexico frequently make reference to Zapata in their campaigns, his image is commonly seen on banners and many chants invoke his name: Si Zapata viviera con nosotros andaría, "If Zapata lived, he would walk with us." Zapata vive, la lucha sigue, "Zapata lives; the struggle continues."

In the folklore of the people of Morelos, there is a widespread belief that Zapata did not die. The corpse purported to be his was that of a friend posing as Zapata, and Zapata himself fled to some obscure rural locale where he continues to evade law enforcement and prepares for a future revolution.

Zapata has in the last few decades been recast as a quasi-religious icon as well, mostly within indigenous or the newer "Zapatista"(EZLN/Mayan) communities, where he is called "Votán Zapata". Votán (Wotán in modern Mayan spelling) is a Mayan god, who with his twin brother Ik'al was said to have descended from the mountains to teach the people to defend themselves. A part of Our Word is Our Weapon by Subcomandante Marcos of the EZLN is dedicated to Votán Zapata.

In popular culture

Zapata has been depicted in comics, books, music and movies. For example, Zapata (1980) is a stage musical written by Harry Nilsson and Perry Botkin which ran for 16 weeks at the Goodspeed Opera House in East Haddam, Connecticut.

Aliases

- "El Tigre del Sur"- Tiger of the South

- "El Tigre"- The Tiger

- "El Tigrillo"- Little Tiger

- "El Caudillo del Sur"- Caudillo of the South

- "El Atila del Sur"- The Attila of the South

Quotes

- Los que no tengan miedo que pasen a firmar. (English translation: "Those who have no fear should step forward to sign this.") This was said when calling on people to sign the Plan de Ayala.

- ¡Tierra y Libertad! (Translation: Land and Liberty)

- Ignorance and obscurantism have never produced anything other than flocks of slaves for tyranny. (In a letter to Pancho Villa)

- The quote Es mejor morir de pie que vivir de rodillas. (Translation: It is better to die on your feet, than to live on your knees.)

- "La tierra es de quien la trabaja." (Translation: The land belongs to those who work it).

- "No hay mas leyes que las de la muelle." (Translation: There are no laws other than the law of the gun.)

- "Seek justice from tyrants not with your hat in your hand, but with a rifle in your fist."

- "I wish to die a slave to principles, not to men."

- "No me dejen morir así, digan que dije algo". ("Don't let me die like this, say I said something"). Presumably his last words.

See also

- Mexican Revolution

- Pancho Villa

- Viva Zapata!

- Paco Ignacio Taibo II, the author of a recently published biography of Pancho Villa: Taibo II, Paco Ignacio. Pancho Villa. Una biografía narrativa. Planeta, México, 2006.

External links

- Google video of Zapata

- Full text html version of Zapata's "Plan de Ayala" in Spanish

- Emiliano Zapata videos

- Bicentenario del inicio del movimiento de Independencia Nacional y del Centenario del inicio de la Revolución Mexicana

References

- ↑ John E. Kicza (1993). The Indian in Latin American History: Resistance, Resilience, and Acculturation. Scholarly Resources. pp. 203. ISBN 0842024212.

- ↑ Diccionario Porrúa de Historia, Biografía y Geografía de México.

- ↑ Horcasitas, 1968

- ↑ Diccionario Porrúa de Historia, Biografía y Geografía de México.

Sources

- "Emiliano Zapata", BBC Mundo.com

- Villa and Zapata by Frank Mclynn

- Fernando Horcasitas, De Porfirio Díaz a Zapata, memoria náhuatl de Milpa Alta, UNAM, México DF.,1968 (eye and ear-witness account of Zapata speaking Nahuatl)

- John Womack, Zapata and the Mexican Revolution, New York, Vintage (1969) ISBN 0394708539

- Enrique Krauze, Zapata: El amor a la tierra, in the Biographies of Power series.

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Zapata Salazar, Emiliano |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Mexican Revolutionary, Army of the South |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 8 August, 1879 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Anenecuilco, Morelos |

| DATE OF DEATH | 10 April, 1919 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Chinameca, Morelos |