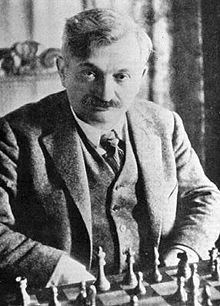

Emanuel Lasker

| Emanuel Lasker | |

|

|

| Full name | Emanuel Lasker |

|---|---|

| Country | Germany |

| Born | |

| Died | |

| World Champion | 1894-1921 |

- This article uses algebraic notation to describe chess moves.

Emanuel Lasker (December 24, 1868 – January 11, 1941) was a German chess player, mathematician, and philosopher who was World Chess Champion for 27 years. In his prime Lasker was one of the most dominant champions, and he is still generally regarded as one of the strongest players ever.

It is often said that Lasker used a "psychological" approach to the game, and even that he sometimes deliberately played inferior moves to confuse opponents. However recent analysis indicates that he was ahead of his time and used a more flexible approach than his contemporaries, which mystified many of them. While it is often said that Lasker spent little time studying the openings, he actually knew the openings well but disagreed with many contemporary analyses. Although Lasker also published chess magazines and two chess books, later players and commentators found it difficult to draw lessons from his methods.

He demanded high fees for playing matches and tournaments, which aroused criticism at the time but contributed to the development of chess as a professional career. The conditions which Lasker demanded for world championship matches in the last 10 years of his reign were controversial, and prompted attempts, particularly by his successor José Raúl Capablanca, to define agreed rules for championship matches.

Lasker was also a talented mathematician, and his Ph.D. thesis is regarded as one of the foundations of modern algebra. He was a first-class contract bridge player and wrote about this and other games, including Go and his own invention, Lasca. His attempt to produce a general theory of competitive activities had some influence on the early development of game theory, and his books about games in general presented a problem which is still considered notable in the mathematical analysis of card games. However his philosophical works and a drama which he co-wrote now receive little attention.

Contents |

Life and career

Early years

Emanuel Lasker was born at Berlinchen in Neumark (now Barlinek in Poland), the son of a Jewish cantor. At the age of 11 he was sent to Berlin to study mathematics, where he lived with his brother Berthold, eight years his senior, who taught him how to play chess. According to Chessmetrics, Berthold was among the world's top ten players in the early 1890s.[1] To supplement their income Emanuel Lasker played chess and card games for small stakes, especially at the Café Kaiserhof.[2][3]

Emanuel Lasker shot up through the chess rankings in 1889, when he won the Café Kaiserhof's annual Winter tournament 1888/89 and the Hauptturnier A ("second division" tournament) at the 6th DSB Congress (German Chess Federation's congress), held in Breslau; finished second in an international tournament at Amsterdam, ahead of some well-known masters including Isidore Gunsberg, who finished third (just half a point out of first place) in the New York 1889 tournament and unsuccessfully challenged for Wilhelm Steinitz' World Chess Championship title, also in 1889.[2][4][5][6] In 1890 he finished third in Graz, then shared first prize with his brother Berthold in a tournament in Berlin.[7][4] In spring 1892 he won two tournaments in London, the second and stronger of these without losing a game.[8][9] At New York 1893 he won all of his 13 games,[10][11][4] one of the few times in chess history that a player has achieved a perfect score in a significant tournament.[12][13][14]

His match record was equally impressive: at Berlin in 1890 he drew a short play-off match against his brother Berthold; and won all his other matches from 1889 to 1893, mostly against top-class opponents: Curt von Bardeleben (1889; ranked 9th by Chessmetrics[15]), Jacques Mieses (1889; 11th[16]), Henry Edward Bird (1890; then 60 years old; 29th[17]), Berthold Englisch (1890; 18th[18]), Joseph Henry Blackburne (1892, without losing a game; Blackburne was aged 51 then, but still 9th in the world[19]), against Jackson Showalter (1892-1893; 22nd[20]) and Celso Golmayo Zúpide (1893; 29th[21]).[6][22] Chessmetrics calculates that Emanuel Lasker became the world's strongest player in mid-1890,[23] and that he was in the top 10 from the very beginning of his recorded career in 1889.[24]

In 1892 Lasker founded the first of his chess magazines, The London Chess Fortnightly, which was published from August 15, 1892 to July 30, 1893. In the second quarter of 1893 there was a gap of 10 weeks between issues, allegedly because of problems with the printer.[25] Shortly after its last issue Lasker traveled to the United States, where he spent the next two years.[26]

Lasker challenged Siegbert Tarrasch, who had won three consecutive great international tournaments (Breslau 1889, Manchester 1890, and Dresden 1892), to a match. Tarrasch haughtily declined, stating that Lasker should first prove his mettle by attempting to win one or two major international events.[27]

Chess 1894-1918

Rebuffed by Tarrasch, Lasker challenged reigning World Champion Wilhelm Steinitz to a match for the title.[27] Initially Lasker wanted to play for US $5,000 a side and a match was agreed at stakes of $3,000 a side, but Steinitz agreed to a series of reductions when Lasker found it difficult to raise the money, and the final figure was $2,000, which was less than for some of Steinitz' earlier matches (the final combined stake of $4,000 would be worth over $495,000 at 2006 values[28]). Although this was publicly praised as an act of sportsmanship on Steinitz' part,[11] Steinitz may have desperately needed the money.[29] The match was played in 1894, at venues in New York, Philadelphia and Montreal. Lasker won convincingly (10 wins, 4 draws, 5 losses); the scores were even after 6 games but Steinitz lost the next 5 in a row.[30] Lasker thus became the second formally-recognized World Chess Champion, and confirmed his title by beating Steinitz even more convincingly in their re-match in 1896-1897 (10 wins, 5 draws, 2 losses).[6]

Influential players and journalists belittled the 1894 match both before and after it took place. Lasker's difficulty in getting backing may have been caused by hostile pre-match comments from Gunsberg and Leopold Hoffer,[11] who had long been a bitter enemy of Steinitz.[31] One of the complaints was that Lasker had never played the other two members of the top four, Siegbert Tarrasch and Mikhail Chigorin[11] – although Tarrasch had rejected a challenge from Lasker in 1892, publicly telling him to go and win an international tournament first.[32][25] After the match some commentators, notably Tarrasch, said Lasker had won mainly because Steinitz was old (58 in 1894).[2][33]

Emanuel Lasker answered these criticisms by creating an even more impressive playing record. Before World War I broke out his most serious "setbacks" were third place at Hastings 1895 (where he may have been suffering from the after-effects of typhoid[2]), tie for second at Cambridge Springs 1904, tie for first at the Chigorin Memorial in St Petersburg 1909 and a drawn match against Carl Schlechter in 1910.[3] He won first prizes at very strong tournaments in St. Petersburg (1895-1896), Nuremberg 1896 chess tournament, London (1899), Paris (1900) and St. Petersburg 1914 chess tournament, where he overcame a 1½ point deficit to finish ahead of the rising stars José Raúl Capablanca and Alexander Alekhine, who later became the next two World Champions; for good measure he also took first prize in a weaker tournament at Trenton Falls (1906).[4][34][35][22] For decades chess writers have reported that Tsar Nicholas II of Russia conferred the title of "Grandmaster of Chess" upon each of the five finalists at St Petersburg 1914 (Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine, Tarrasch and Marshall), but chess historian Edward Winter has questioned this, stating that the earliest known sources supporting this story were published in 1940 and 1942.[36][37][38]

Lasker's match record was as impressive between his 1896-1897 re-match with Steinitz and 1914: he won all but one of his normal matches, and three of those were convincing defenses of his title, against Marshall (1907; 11½−3½), Tarrasch (1908; 10½−5½) and Dawid Janowski (1910; 9½−1½).[39] He also played several exhibition matches, potentially lucrative entertainments for well-off enthusiasts.[40] A 1909 match against Janowski has sometimes been called a world championship match,[41] but contemporary references indicate it was not.[42]

However Lasker only scraped a draw in the 10-game match against Schlechter in 1910 by winning the last game that was played, creating a mystery that has not yet been solved. This match was originally meant to consist of 30 games, but was cut to 10 when it became obvious that there were insufficient funds to meet Lasker's demand for a fee of 1,000 marks per game played.[26] It is generally regarded as a World Championship match, but one post-match press report cast doubt on this.[43] It is also difficult to explain Schlechter's decision to play for a win in the 10th game, when he could have forced a draw quite easily and thus won the match as he was one point ahead. Some commentators have argued that there was a secret clause that required Schlechter to have a two-game lead in order to claim victory.[44][45] However Lasker himself wrote 2 days before the 10th game, "The match with Schlechter is nearing its end and it appears probable that for the first time in my life I shall be the loser. If that should happen a good man will have won the world championship,"[46] which implies that it really was a world title match and that there was no secret "two-game lead" clause. Another report shortly after the end of the match appears to speculate that Schlechter threw the last game because a narrow victory for him would not have been in the financial interests of either player, as they would have had to play another match if Schlechter won narrowly, but they had not been able to get adequate financial backing for the 1910 match.[47] It has even been suggested that Schlechter played to win the last game because he was too honorable to win the title by a fluke, having won the 5th game by a swindle in a lost position.[48]

In 1911 Lasker received a challenge for a world title match against the rising star José Raúl Capablanca. Lasker was unwilling to play the traditional "first to win 10 games" type of match in the semi-tropical conditions of Havana, especially as drawn games were becoming more frequent and the match might last for over 6 months. He therefore made a counter-proposal: if neither player a had a lead of at least 2 games by the end of the match, it should be considered a draw; the match should be limited to the best of 30 games, counting draws; except that if either player won six games and led by at least two games before 30 games were completed, he should be declared the winner; the champion should decide the venue and stakes, and should have the exclusive right to publish the games; the challenger must deposit a forfeit of US $2,000 (equivalent to over $194,000 in 2006 values[49]); the time limit should be 12 moves per hour; play should be limited to two 2½ hour sessions per day, five days a week. Capablanca objected to the time limit, the short playing times, the 30-game limit, and especially the requirement that he must win by two games to claim the title, which he regarded as unfair. Lasker took offence at the terms in which Capablanca criticized the two-game lead condition and broke off negotiations, and until 1914 Lasker and Capablanca were not on speaking terms. However at the 1914 St. Petersburg tournament Capablanca proposed a set of rules for the conduct of world championship matches, which were accepted by all the leading players including Lasker.[50]

Late in 1912 Lasker entered into negotiations for a world title match with Akiba Rubinstein, whose tournament record for the previous few years had been on a par with Lasker's and a little ahead of Capablanca's.[51] The two players agreed to play a match if Rubinstein could raise the funds, but Rubinstein had few rich friends to back him and the match was never played. The start of World War I put an end to hopes that Lasker would play either Rubinstein or Capablanca for the world championship in the near future.[44]

Throughout World War I (1914-1918) Lasker played in only two serious chess events. He convincingly won (5½−½) a non-title match against Tarrasch in 1916.[52] In September to October 1918, shortly before the armistice of 11 November 1918, he won a quadrangular (4-player) tournament, ½ point ahead of Rubinstein.[53]

Lasker was shocked by the poverty in which Steinitz died and did not intend to die in similar circumstances.[54] He became notorious for demanding high fees for playing matches and tournaments, and he argued that players should own the copyright in their games rather than let publishers get all the profits.[2][55] After winning the 1904 Cambridge Springs tournament Marshall challenged Lasker to a match for the World Championship but could not raise the stakes demanded by Lasker until 1907.[40] Other players resented Lasker's "hunger for money" but most of them soon realized that his attitude was sensible.[2]

Academic activities 1894-1918

Despite his superb playing results, chess was not Lasker's only interest. His parents recognized his intellectual talents, especially for mathematics, and sent the adolescent Emanuel to study in Berlin (where he found he also had a talent for chess). Lasker gained his abitur (high school graduation certificate) at Landsberg an der Warthe, now a Polish town named Gorzow Wielkopolski but then part of Prussia. He then studied mathematics and philosophy at the universities in Berlin, Göttingen and Heidelberg.[40]

In 1895 Lasker published two mathematical articles in Nature[56] On the advice of David Hilbert he registered for doctoral studies at Erlangen during 1900-1902.[40] In 1901 he presented his doctoral thesis Über Reihen auf der Convergenzgrenze ("On Series at Convergence Boundaries") at Erlangen and in the same year it was published by the Royal Society.[57][58] He was awarded a doctorate in mathematics in 1902.[40] His most significant mathematical article, in 1905, published a theorem of which Emmy Noether developed a more generalized form, which is now regarded as of fundamental importance to modern algebra and algebraic geometry.[59][40]

Lasker held short-term positions as a mathematics lecturer at: Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana (1893); and Victoria University in Manchester, England (1901; Victoria University was one of the "parents" of the current University of Manchester).[40] However he was unable to secure a longer-term position, and pursued his scholarly interests independently.[60]

In 1906 Lasker published a booklet titled Kampf (Struggle),[61] in which he attempted to create a general theory of all competitive activities, including chess, business and war; this later had some influence on von Neumann's work on game theory.[62] He produced two other books which are generally categorized as philosophy, Das Begreifen der Welt (Comprehending the World; 1913) and Die Philosophie des Unvollendbar (The Philosophy of the Unattainable; 1918).[40]

Other activities 1894-1918

In 1896-1897 Lasker published his book Common Sense in Chess, based on lectures he had given in London in 1895.[63]

In Lasker 1903 played in Ostend against Mikhail Chigorin a 6-game match that was sponsored by the wealthy lawyer and industrialist Isaac Rice in order to test the Rice Gambit.[64] Lasker narrowly lost the match. Three years later Lasker became secretary of the Rice Gambit Association, founded by Rice in order to promote the Rice Gambit,[26] and in 1907 Lasker quoted with approval Rice's views on the convergence of chess and military strategy.[65]

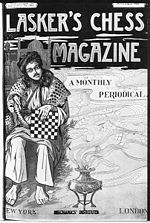

In November 1904, Lasker founded Lasker's Chess Magazine, which ran until 1909.[66]

For a short time in 1906 Emanuel Lasker was interested in the Japanese strategy game Go, but soon returned to chess. Curiously he was introduced to the game by his namesake Edward Lasker, who wrote a successful book Go and Go-Moku in 1934.[67]

At the age of 42, in 1911, Lasker married Martha Cohn (née Bamberger), a rich widow who was a year older than Lasker and already a grandmother. They lived in Berlin.[26] Martha Cohn wrote popular stories under the pseudonym "L. Marco".[60]

During World War I, Lasker invested all of his savings in German war bonds. Since Germany lost the war, Lasker lost all his money. During the war, he wrote a book which claimed that civilization would be in danger if Germany lost the war.[26]

1918 to end of life

In January 1920 Lasker and José Raúl Capablanca signed an agreement to play a world championship match in 1921, noting that Capablanca was not free to play in 1920. Because of the delay Lasker insisted on a final clause that: allowed him to play anyone else for the championship in 1920; nullified the contract with Capablanca if Lasker lost a title match in 1920; and stipulated that if Lasker resigned the title Capablanca should become world champion. Lasker had previously included in his agreement before World War I to play Akiba Rubinstein for the title a similar clause that if he resigned the title, it should become Rubinstein's.[68]

A report in the American Chess Bulletin (July-August 1920 issue) said that Lasker had resigned the world title in favor of Capablanca because the conditions of the match were unpopular in the chess world. The American Chess Bulletin speculated that the conditions were not sufficiently unpopular to warrant resignation of the title, and that Lasker's real concern was that there was not enough financial backing to justify his devoting 9 months to the match.[68] When Lasker resigned the title in favor of Capablanca he was unaware that enthusiasts in Havana had just raised $20,000 to fund the match provided it was played there. When Capablanca learned of Lasker's resignation he went Holland, where Lasker was living at the time, to inform him that Havana would finance the match. In August 1920 Lasker agreed to play in Havana, but insisted that he was the challenger as Capablanca was now the champion. Capablanca signed an agreement that accepted this point, and soon afterwards published a letter confirming this. Lasker also stated that, if he beat Capablanca, he would resign the title so that younger masters could compete for it.[68] The match was played in March to April 1921 and Lasker resigned it after 14 games, when he was trailing by 4 games and had won none.[50]

By this time Lasker was nearly 53 years old, and he never played another serious match; [52][69] his only other match was a short exhibition against Frank James Marshall in 1940, which he won. After winning the New York 1924 chess tournament (1½ points ahead of Capablanca) and finishing 2nd at Moscow in 1925 (1½ points behind Efim Bogoljubow, ½ point ahead of Capablanca),[70] he effectively retired from serious chess.[3]

During the Moscow 1925 chess tournament, Emanuel Lasker received a telegram informing him that the drama written by himself and his brother Berthold , Vom Menschen die Geschichte ("History of Mankind"), had been accepted for performance at the Lessing theatre in Berlin. Emanuel Lasker was so distracted by this news that he lost badly to Carlos Torre the same day.[71] The play was not a success and has little literary value.[60]

In 1926 Lasker wrote Lehrbuch des Schachspiels, which he re-wrote in English in 1927 as Lasker's Manual of Chess.[72] He also wrote books on other games of mental skill: Encyclopedia of Games (1929) and Das verständige Kartenspiel (means "Sensible Card Play"; 1929; English translation in the same year), both of which posed a problem in the mathematical analysis of card games;[73] Brettspiele der Völker ("Board Games of the Nations"; 1931), which includes 30 pages about Go[74] and a section about a game he had invented in 1911, Lasca;[75] and Das Bridgespiel ("The Game of Bridge"; 1931).[76] Lasker became an expert bridge player, representing Germany at international events in the early 1930s,[26] and a registered teacher of the Culbertson system.[77]

In October 1928 Emanuel Lasker's brother Berthold died.[26]

Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in January 1933, gained dictatorial powers in March 1933, and in April 1933 started a campaign of discrimination and intimidation against Jews. Lasker and his wife Martha, who were both Jews, left Germany in 1933, and all their assets in Germany were confiscated. After a short stay in England, in 1935 they were invited to live in the USSR by Nikolai Krylenko, the Commissar of Justice who was responsible for the Moscow show trials and, in his other capacity as Sports Minister, was an enthusiastic supporter of chess.[60] In the USSR Lasker renounced his German citizenship and received Soviet citizenship,[78] and was given a post, probably honorary, at Moscow's Institute for Mathematics.[60] Lasker returned to competitive chess to make some money, finishing 5th in Zürich 1934 and 3rd in Moscow 1935 (undefeated, ½ point behind Mikhail Botvinnik and Salo Flohr; ahead of Capablanca, Rudolf Spielmann and several Soviet masters), 6th in Moscow 1936 and 7th equal in Nottingham 1936.[79] His performance in Moscow 1935 at age 67 was hailed as "a biological miracle."[80]

Unfortunately Stalin's Great Purge started at about the same time the Laskers arrived in the USSR. In 1937, after a trip to New York to visit relatives, Martha and Emanuel Lasker decided to stay in the United States.[60] In the following year Emanuel Lasker's patron Krylenko was purged. Martha Lasker died in 1937, soon after the couple took residence in the USA. Lasker tried to support himself by giving chess and bridge lectures and exhibitions, as he was now too old for serious competition.[60][26] In 1940 he published his last book, The Community of the Future, in which he proposed solutions for serious political problems, including anti-Semitism and unemployment.[60] He died of a kidney infection in New York on January 11, 1941, at the age of 72, as a charity patient at Mount Sinai Hospital.[26]

Assessment

Chess strength and style

Lasker is often said to have used a "psychological" method of play in which he considered the subjective qualities of his opponent, in addition to the objective requirements of his position on the board. Richard Réti even speculated that Lasker would sometimes knowingly choose inferior moves if he knew they would make his opponent uncomfortable. However Lasker himself denied this, and most modern writers agree. According to Grandmaster Andrew Soltis and International Master John L. Watson, the features that made his play mysterious to contemporaries now appear regularly in modern play: the g2-g4 "Spike" attack against the Dragon Sicilian; sacrifices to gain positional advantage; playing the "practical" move rather than trying to find the best move; counterattacking and complicating the game before a disadvantage became serious.[81][82] Former World Champion Vladimir Kramnik writes, "He realized that different types of advantage could be interchangeable: tactical edge could be converted into strategic advantage and vice versa," which mystified contemporaries who were just becoming used to the theories of Steinitz as codified by Siegbert Tarrasch.[83]

The famous last round win against Capablanca (St. Petersburg, 1914), which Lasker needed in order to win the tournament, is sometimes offered as evidence of his "psychological" style; but Kramnik argues that his play in this game demonstrated deep positional understanding, rather than psychology.[83] Reuben Fine describes Lasker's choice of opening, the Exchange Variation of the Ruy Lopez, as "innocuous but psychologically potent."[3] However an analysis of Lasker's use of this variation throughout his career concludes that: Lasker used the variation only 14 times in his career, from the 13th game of his 1894 match against Wilhelm Steinitz (who won that game) to his final-round win against Frank James Marshall in the 1924 New York Tournament (Lasker already had a winning lead in the tournament); almost all his uses of it were against top-class opponents; he was very successful with it (in serious events: 10 wins, 3 draws and the one loss to Steinitz); early in his career he apparently used it as a safe option with little risk of losing the game; later he gained confidence in the variation and even used it in a couple of "must-win" situations, including against Capablanca at St. Petersburg in 1914. Lasker also won the three recorded games in which he played the variation as Black; one was against Alekhine, in the 1914 St. Petersburg Tournament, the day before Lasker, playing as White, beat Capablanca with it.[84]

Many commentators write that Lasker paid little attention to the openings.[3] However Capablanca wrote that Lasker knew the openings very well, although he often disagreed with a lot of contemporary opening analysis. In fact before the 1894 world title match Lasker studied the openings thoroughly, especially Steinitz' favorite lines. Capablanca also wrote that, in his opinion, no player surpassed Lasker in the ability to assess a position quickly and accurately, in terms of who had the better prospects of winning and what strategy each side should adopt.[85] Even when Lasker was in his late 60s, Capablanca considered him the most dangerous player around in any single game.

In addition to his enormous chess skill Lasker had an excellent competitive temperament: his bitter rival Siegbert Tarrasch once said, "Lasker occasionally loses a game, but he never loses his head."[3] Although very strong in matches, he was even stronger in tournaments. For example, Capablanca could not finish ahead of him until 15 years after their 1921 match, by which time Lasker was 68 years old.[3] Lasker enjoyed the need to adapt to varying styles and to the shifting fortunes of tournaments.[2]

In 1964, Chessworld magazine published an article in which future World Champion Bobby Fischer listed the ten greatest players in history.[86] Fischer did not include Lasker in the list, deriding him at page 59 as a "coffee-house player [who] knew nothing about openings and didn't understand positional chess." However, Pal Benko said that Fischer later reconsidered, telling Benko that "Lasker was a truly great player."[87]

Statistical ranking systems place Lasker high among the greatest players of all time. "Warriors of the Mind" places him 6th, behind Garry Kasparov, Anatoly Karpov, Bobby Fischer, Mikhail Botvinnik and José Raúl Capablanca.[88] In his 1978 book The Rating of Chessplayers, Past and Present, Arpad Elo gave retrospective ratings to players based on their performance over the best five-year span of their career. He concluded that Lasker was the joint 2nd strongest player of those surveyed (tied with Botvinnik and behind Capablanca).[89] The most up-to-date system, Chessmetrics, is rather sensitive to the length of the periods being compared, and ranks Lasker between 5th and 2nd strongest of all time for peak periods ranging in length from 1 to 20 years.[90] Its author, Jeff Sonas, concluded that only Kasparov and Karpov surpassed Lasker's long-term dominance of the game.[91]

Influence on chess

Lasker founded no school of players who used a similar approach to the game.[3] Max Euwe, world champion 1935-1937 and a prolific writer of chess manuals, said, "It is not possible to learn much from him. One can only stand and wonder."[92] Euwe had a lifetime 0-3 score against Lasker.[93]

There are several "Lasker Variations" in the chess openings, including Lasker's Defense to the Queen's Gambit, Lasker's Defense to the Evans Gambit (which effectively ended the use of this gambit in tournament play),[94] and the Lasker Variation in the McCutcheon Variation of the French Defense.[95]

One of Lasker's most famous games is Lasker - Bauer, Amsterdam, 1889, in which he sacrificed both bishops in a maneuver later repeated in a number of games. Similar sacrifices had already been played by Cecil Valentine De Vere and John Owen, but these were not in major events and Lasker probably had not seen them.[92]

Lasker's high financial demands and his demand to own the copyright in his games initially angered editors and other players, but helped to pave the way for the rise of full-time chess professionals who earn most of their living from playing, writing and teaching.[2] Copyright in chess games had been contentious at least as far back as the mid-1840s,[96] and Steinitz and Lasker vigorously asserted that players should own the copyright and wrote copyright clauses into their match contracts.[97] However his demands that challengers should raise large purses prevented or delayed some eagerly-awaited world championship matches,[40][44] and this problem continued throughout the reign of his successor Capablanca.[98][99]

Some of the controversial conditions that Lasker insisted on for championship matches led Capablanca to attempt twice (1914 and 1922) to publish rules for such matches, to which other top players readily agreed.[50][100]

Work in other fields

Despite the relatively small amount of time Lasker spent working on mathematics, he produced a theorem which, after a further refinement, became one of the foundations of modern algebra.[40] His attempt to create a general theory of all competitive activities had some influence on von Neumann's work on game theory,[62] and his later writings about card games presented a significant issue in the mathematical analysis of card games.[73]

However, his dramatic and philosophical works have never been highly regarded.[60]

Friends and relatives

Lasker was a good friend of Albert Einstein, who wrote the introduction to a book about him.[101]

Poetess Else Lasker-Schüler was his sister-in-law. Edward Lasker, born in Kempen (Kępno), Greater Poland (then Prussia), the German-American chess master, engineer, and author, claimed that he was distantly related to Emanuel Lasker.[102][103] They both played in the great New York 1924 chess tournament.[104]

Publications

Chess

- The London Chess Fortnightly, 1892–1893[25]

- Lasker's Chess Magazine, OCLC 5002324, 1904-1907.[26]

- Lasker's Manual of Chess, 1925, is as famous in chess circles for its philosophical tone as for its content.[105]

- Common Sense in Chess, 1896-1897

- Lehrbuch des Schachspiels, 1926 – English version Lasker's Manual of Chess published in 1927.

Mathematics

- Lasker, Emanuel (August 1895). "Metrical Relations of Plane Spaces of n Manifoldness". Nature 52 (1345): 340–343. doi:. http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/052340d0. Retrieved on 2008-05-31.

- Lasker, Emanuel (October 1895). "About a certain Class of Curved Lines in Space of n Manifoldness". Nature 52 (1355): 596. doi:. http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/052596a0. Retrieved on 2008-05-31.

- Lasker, Emanuel (1901). "Über Reihen auf der Convergenzgrenze ("On Series at Convergence Boundaries")". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A 196: 431–477. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1901RSPTA.196..431L. Retrieved on 2008-05-31. – Lasker's Ph.D. thesis.

- Lasker, E. (1905), "Zur Theorie der Moduln und Ideale", Math. Ann. 60: 19–116, doi:

Other games

- Kampf (Struggle), 1906.

- Encyclopedia of Games, 1929.

- Das verständige Kartenspiel (Sensible Card Play), 1929 – English translation published in the same year.

- Brettspiele der Völker (Board Games of the Nations), 1931 – includes sections about Go and Lasca.

- Das Bridgespiel ("The Game of Bridge"), 1931.

Philosophical

- Das Begreifen der Welt (Comprehending the World), 1913.

- Die Philosophie des Unvollendbar (The Philosophy of the Unattainable), 1918.

- Vom Menschen die Geschichte ("History of Mankind"), 1925 – a play, co-written with his brother Berthold .

- The Community of the Future, 1940.

Quotations

- "The acquisition of harmonious education is comparable to the production and the elevation of an organism harmoniously built. The one is fed by blood, the other one by the spirit; but Life, equally mysterious, creative, powerful, flows through either." — from Manual of Chess

- "Lies and hypocrisy do not survive for long on the chessboard. The creative combination lies bare the presumption of a lie, while the merciless fact, culminating in a checkmate, contradicts the hypocrite." — from Manual of Chess

Notable games

- Lasker vs Johann Hermann Bauer, Amsterdam 1889, Bird Opening: Dutch Variation (A03), 1-0 Although this was not the earliest known game with a successful two bishops sacrifice, this combination is now known as a "Lasker-Bauer combination" or "Lasker sacrifice".[92]

- Harry Nelson Pillsbury-Lasker, St Petersburg 1895, Queen's Gambit Declined: Pseudo-Tarrasch. Primitive Pillsbury Variation (D50), 0-1 A brilliant sacrifice in the 17th move leads to a victorious attack.

- Wilhelm Steinitz vs Emanuel Lasker, London (England) 1899 The old champion and the new one really go for it.

- Frank James Marshall vs Emanuel Lasker Lasker's attack is insufficient for a quick win, so he trades it in for an endgame in which he quickly ties Marshall in knots.

- Emanuel Lasker vs Carl Schlechter, match 1910, game 10 Not a great game, but the one that saved Emanuel Lasker from losing his world title in 1910. The notes are said to be by José Raúl Capablanca.

- Lasker-Jose Raul Capablanca, St Petersburg 1914, Ruy Lopez: Exchange. Alekhine Variation (C68), 1-0 Lasker, who needed a win here, surprisingly used a quiet opening, allowing Capablanca to simplify the game early. There has been much debate about whether Lasker's approach represented subtle psychology or deep positional understanding.

- Max Euwe vs Emanuel Lasker, Zurich 1934 66-year old Lasker beats a future world champion, sacrificing his Queen to turn defense into attack.

Tournament results

Here are Lasker's placings and scores in tournaments:[4][34][35][70][79][26][106]

- Under Score, + games won, − games lost, = games drawn

| Date | Location | Place | Score | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1888/89 | Berlin (Café Kaiserhof) | 1st | 20/20 | +20−0=0 | |

| 1889 | Breslau "B" | 1st = | 12/15 | +11−2=2 | Tied with von Feyerfeil and won the play-off. This was Hauptturnier A of the 6th DSB Congress, i.e. the "second-division" tournament. |

| 1889 | Amsterdam "A" tournament | 2nd | 6/8 | +5−1=2 | Behind Amos Burn; ahead of James Mason , Isidor Gunsberg and others. This was the stronger of the two Amsterdam tournaments held at that time. |

| 1890 | Berlin | 1–2 | 6½/8 | +6−1=1 | Tied with his brother Berthold Lasker. |

| 1890 | Graz | 3rd | 4/6 | +3−1=2 | Behind Gyula Makovetz and Johann Hermann Bauer. |

| 1892 | London | 1st | 9/11 | +8−1=2 | Ahead of Mason and Rudolf Loman.[9] |

| 1892 | London | 1st | 6½/8 | +5−0=3 | Ahead of Joseph Henry Blackburne, Mason, Gunsberg and Henry Edward Bird. |

| 1893 | New York City | 1st | 13/13 | +13−0=0 | Ahead of Adolf Albin, Jackson Showalter and a newcomer called Harry Nelson Pillsbury. |

| 1895 | Hastings | 3rd | 15½/21 | +14−4=3 | Behind Pillsbury and Mikhail Chigorin; ahead of Siegbert Tarrasch, Wilhelm Steinitz and the rest of a strong field. |

| 1895/96 | St. Petersburg | 1st | 6½/8 | +6−1=1 | A Quadrangular tournament; ahead of Steinitz (by 2 points), Pillsbury and Chigorin. |

| 1896 | Nuremberg | 1st | 13½/18 | +12−3=3 | Ahead of Géza Maróczy, Pillsbury, Tarrasch, Dawid Janowski, Steinitz and the rest of a strong field. |

| 1899 | London | 1st | 23½/28 | +20−1=7 | Ahead of Janowski, Pillsbury, Maróczy, Carl Schlechter, Blackburne, Chigorin and several other strong players. |

| 1900 | Paris | 1st | 14½/16 | +14−1=1 | Ahead of Pillsbury (by 2 points), Frank James Marshall, Maróczy, Burn, Chigorin and several others. |

| 1904 | Cambridge Springs | 2nd = | 11/15 | +9−2=4 | Tied with Janowski; 2 points behind Marshall; ahead of Georg Marco, Showalter, Schlechter, Chigorin, Jacques Mieses, Pillsbury and others. |

| 1906 | Trenton Falls | 1st | 5/6 | +4−0=2 | A Quadrangular tournament; ahead of Curt, Albert Fox and Raubitschek. |

| 1909 | St. Petersburg | 1st = | 14½/18 | +13−2=3 | Tied with Akiba Rubinstein; ahead of Oldrich Duras and Rudolf Spielmann (by 3½ points), Ossip Bernstein, Richard Teichmann and several other strong players. |

| 1914 | St. Petersburg | 1st | 13½/18 | +10−1=7 | Ahead of José Raúl Capablanca, Alexander Alekhine, Tarrasch and Marshall. This tournament had an unusual structure: there was a preliminary tournament in which 11 players played each other player once; the top 5 players then played a separate final tournament in which each player who made the "cut" played the other finalists twice; but their scores from the preliminary tournament were carried forward. Even the preliminary tournament would now be considered a "super-tournament". Capablanca "won" the preliminary tournament by 1½ points without losing a game, but Lasker achieved a plus score against all his opponents in the final tournament and finished with a combined score ½ point ahead of Capablanca's. |

| 1918 | Berlin | 1st | 4½/6 | +3−0=3 | Quadrangular tournament. Ahead of Rubinstein, Schlechter and Tarrasch. |

| 1923 | Mährisch-Ostrau | 1st | 10½/13 | +8−0=5 | Ahead of Richard Réti, Ernst Grünfeld, Alexey Selezniev, Savielly Tartakower, Max Euwe and other strong players. |

| 1924 | New York City | 1st | 16/20 | +13−1=6 | Ahead of Capablanca (by 1½ points), Alekhine, Marshall, and the rest of a very strong field. |

| 1925 | Moscow | 2nd | 14/20 | +10−2=8 | Behind Efim Bogoljubow; ahead of Capablanca, Marshall, Tartakower, Carlos Torre, other strong non- Soviet players and the leading Soviet players. |

| 1934 | Zürich | 5th | 10/15 | +9−4=2 | Behind Alekhine, Euwe, Salo Flohr and Bogoljubow; ahead of Bernstein, Aron Nimzowitsch, Gideon Stahlberg and various others. |

| 1935 | Moscow | 3rd | 12½/19 | +6−0=13 | ½ point behind Mikhail Botvinnik and Flohr; ahead of Capablanca, Spielmann, Ilya Kan, Grigory Levenfish, Andor Lilienthal, Viacheslav Ragozin and others. Emanuel Lasker was about 67 years old at the time. |

| 1936 | Moscow | 6th | 8/18 | +3−5=10 | Capablanca won. |

| 1936 | Nottingham | 7–8th | 8½/14 | +6−3=5 | Capablanca and Botvinnik tied for 1st place. |

Match results

Here are Lasker's results in matches:[6][39][52][22]

- Under Score, + games won, − games lost, = games drawn

| Date | Opponent | Result | Location | Score | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1889 | E.R. von Feyerfeil | Won | Breslau | 1−0 | +1−0=0 | Play-off match |

| 1889/90 | Curt von Bardeleben | Won | Berlin | 2½−1½ | +2−1=1 | |

| 1889/90 | Jacques Mieses | Won | Leipzig | 6½−1½ | +5−0=3 | |

| 1890 | Berthold Lasker | Drew | Berlin | ½−½ | +0−0=1 | Play-off match |

| 1890 | Henry Edward Bird | Won | Liverpool | 8½−3½ | +7−2=3 | |

| 1890 | N.T. Miniati | Won | Manchester | 4−1 | +3−0=2 | |

| 1890 | Berthold Englisch | Won | Vienna | 3½−1½ | +2−0=3 | |

| 1891 | Francis Joseph Lee | Won | London | 1½−½ | +1−0=1 | |

| 1892 | Joseph Henry Blackburne | Won | London | 8−2 | +6−0=4 | |

| 1892 | Bird | Won | Newcastle upon Tyne | 5−0 | +5−0=0 | |

| 1892/93 | Jackson Showalter | Won | Logansport, Kokomo | 7−3 | +6−2=2 | |

| 1893 | Celso Golmayo Zúpide | Won | Havana | 2½−½ | +2−0=1 | |

| 1893 | Andrés Clemente Vázquez | Won | Havana | 3−0 | +3−0=0 | |

| 1893 | A. Ponce | Won | Havana | 2−0 | +2−0=0 | |

| 1893 | Alfred Ettlinger | Won | New York City | 5−0 | +5−0=0 | |

| 1894 | Wilhelm Steinitz | Won | New York, Philadelphia, Montreal | 12−7 | +10−5=4 | World Championship match |

| 1896/97 | Steinitz | Won | Moscow | 12½−4½ | +10−2=5 | World Championship match |

| 1901 | Dawid Janowski | Won | Manchester | 1½−½ | +1−0=1 | |

| 1903 | Mikhail Chigorin | Lost | Brighton | 2½−3½ | +1−2=3 | Rice Gambit match |

| 1907 | Frank James Marshall | Won | New York, Philadelphia, Washington DC, Baltimore, Chicago, Memphis | 11½−3½ | +8−0=7 | World Championship match |

| 1908 | Siegbert Tarrasch | Won | Düsseldorf, Munich | 10½−5½ | +8−3=5 | World Championship match |

| 1908 | Abraham Speijer | Won | Amsterdam | 2½−½ | +2−0=1 | |

| 1909 | Janowski | Drew | Paris | 2−2 | +2−2=0 | |

| 1909 | Janowski | Won | Paris | 8−2 | +7−1=2 | Exhibition match |

| 1910 | Carl Schlechter | Drew | Vienna−Berlin | 5−5 | +1−1=8 | World Championship match |

| 1910 | Janowski | Won | Berlin | 9½−1½ | +8−0=3 | World Championship match |

| 1914 | Ossip Bernstein | Drew | Moscow | 1−1 | +1−1=0 | Exhibition match |

| 1916 | Tarrasch | Won | Berlin | 5½−½ | +5−0=1 | |

| 1921 | José Raúl Capablanca | Lost | Havana | 5−9 | +0−4=10 | lost World Championship |

| 1940 | Frank James Marshall | Lost | New York | ½−1½ | +0−1=1 | exhibition match |

See also

- List of people who have beaten Emanuel Lasker in chess

References

- ↑ "Chessmetrics Player Profile: Berthold Lasker". Retrieved on 2008-05-30.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Tyle, L.B., ed. (2002). UXL Encyclopedia of World Biography. U·X·L. ISBN 0787664650. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_gx5229/is_2003/ai_n19151908. Retrieved on 2008-05-30.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Fine, R. (1952). The World's Great Chess Games. Andre Deutsch (now as paperback from Dover).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 "I tornei di scacchi dal 1880 al 1899". Retrieved on 2008-05-29.

- ↑ Thulin, A. (August 2007). "Steinitz—Chigorin, Havana 1899 [sic - A World Championship Match or Not?]" (PDF). Retrieved on 2008-12-03.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 "I matches 1880/99". Retrieved on 2008-05-29.

- ↑ Gino Di Felice, Chess Results, 1747-1900, McFarland & Company, 2004, p. 121, 123. ISBN 0-7864-2041-3.

- ↑ Gino Di Felice, Chess Results, 1747-1900, McFarland & Company, 2004, pp. 133, 134. ISBN 0-7864-2041-3.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Gillam, A.J. (2008). London March 1892; London March/April 1892; Belfast 1892. The Chess Player. ISBN 1-901034-59-8. http://www.schachversand.de/e/detail/buecher/9414.html. Retrieved on 2008-11-23.

- ↑ Gino Di Felice, Chess Results, 1747-1900, McFarland & Company, 2004, p. 142. ISBN 0-7864-2041-3.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 ""Ready for a big chess match"". New York times. 11 March 1894. http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?_r=2&res=9400E4DF1630E033A25752C1A9659C94659ED7CF&oref=slogin&oref=slogin. Retrieved on 2008-05-30. Note: this article implies that the combined stake was $4,500, but Lasker wrote that it was $4,000: "From the Editorial Chair". Lasker's Chess Magazine 1. January 1905. http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Lasker's_Chess_Magazine/Volume_1. Retrieved on 2008-05-31.

- ↑ David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld, The Oxford Companion to Chess (2nd ed. 1992), Oxford University Press, p. 81. ISBN 0-19-866164-9.

- ↑ Andy Soltis, Chess Lists Second Edition, McFarland and Company, 2002, pp. 81-83. IBSN 0786412968.

- ↑ Anne Sunnucks, The Encyclopaedia of Chess, St. Martin's Press, 1970, p. 76.

- ↑ "Chessmetrics Player Profile: Curt von Bardeleben". Retrieved on 2008-05-30.

- ↑ "Chessmetrics Player Profile: Jacques Mieses". Retrieved on 2008-05-30.

- ↑ "Chessmetrics Player Profile: Henry Bird". Retrieved on 2008-05-30.

- ↑ "Chessmetrics Player Profile: Berthold Englisch". Retrieved on 2008-05-30.

- ↑ "Chessmetrics Player Profile: Joseph Blackburne". Retrieved on 2008-05-30.

- ↑ "Chessmetrics Player Profile: Jackson Showalter". Retrieved on 2008-05-30.

- ↑ "Chessmetrics Player Profile: Celso Golmayo Zupide". Retrieved on 2008-05-30.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Select the "Career details" option at "Chessmetrics Player Profile: Emanuel Lasker (career details)". Retrieved on 2008-05-30.

- ↑ "Chessmetrics Monthly Lists: 1885 - 1895". Retrieved on 2008-05-30.

- ↑ "Chessmetrics Summary: 1885 - 1895". Retrieved on 2008-05-30.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Emanuel Lasker (PDF). The London Chess Fortnightly. Moravian Chess. http://www.chesscafe.com/text/review302.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-06-06.

- ↑ 26.00 26.01 26.02 26.03 26.04 26.05 26.06 26.07 26.08 26.09 26.10 Bill Wall. "Dr. Emanuel Lasker (1868-1941)". Retrieved on 2007-08-03.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Dr. J. Hannak, Emanuel Lasker: The Life of a Chess Master, Simon and Schuster, 1959, p. 31.

- ↑ Using incomes for the adjustment factor, as the outcome depended on a few months' hard work by the players; if prices are used for the conversion, the result is over $99,000 - see "Six Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount, 1774 to Present". Retrieved on 2008-05-30. However Lasker later published an analysis showing that the winning player got $1,600 and the losing player $600 out of the $4,000, as the backers who had bet on the winner got the rest: "From the Editorial Chair". Lasker's Chess Magazine 1. January 1905. http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Lasker's_Chess_Magazine/Volume_1. Retrieved on 2008-05-31.

- ↑ "The Steinitz Papers - review". Retrieved on 2008-05-30.

- ↑ "Lasker v. Steinitz - World Championship Match 1894". Retrieved on 2008-05-30.

- ↑ Winter, E.. "Kasparov, Karpov and the Scotch". Retrieved on 2008-05-30.

- ↑ "Emanuel Lasker". Retrieved on 2008-06-05.

- ↑ "Chess World Champions – Emanuel Lasker". Retrieved on 2008-11-21.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "I tornei di scacchi dal 1900 al 1909". Retrieved on 2008-05-29.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "I tornei di scacchi dal 1910 al 1919". Retrieved on 2008-05-29.

- ↑ Winter, Edward (1999), Kings, Commoners and Knaves: Further Chess Explorations (1 ed.), Russell Enterprises, Inc., pp. 315–316, ISBN 1-888690-04-6

- ↑ Winter, Edward (2003), A Chess Omnibus (1 ed.), Russell Enterprises, Inc., pp. 177–178, ISBN 1-888690-17-8

- ↑ Edward Winter. "Chess Note 5144: Tsar Nicholas II". Retrieved on 2008-11-21.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "I matches 1900/14". Retrieved on 2008-05-29.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 40.5 40.6 40.7 40.8 40.9 "Lasker biography". Retrieved on 2008-05-31.

- ↑ For instance Israel Horowitz (1973). From Morphy to Fischer. Batsford. pp. 63-64. and Raymond Keene and David Goodman (1986). The Centenary Match - Kasparov-Karpov III. Batsford. p. 6.

- ↑ Edward Winter. "Chess Notes 5199". Retrieved on 2008-06-03.

- ↑ Buckley, J.R. (June 1910), , American Chess Bulletin, http://www.chesshistory.com/winter/extra/buckley.html, retrieved on 2008-05-30 reported that the 10-game match was not for the World Championship, and that its result suggested "a contest on different terms, a match for the world championship"; but at the foot of this article the ACB’s editor added that Lasker had told him, "Yes, I placed the title at stake."

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Horowitz, I.A. (1973). From Morphy to Fischer. Batsford.

- ↑ Wilson, F. (1975,). Classical Chess Matches, 1907-1913. Dover. ISBN 0486231453. http://members.aol.com/graemecree/chesschamps/world/world1910.htm. Retrieved on 2008-05-30.

- ↑ , New York Evening Post, February 6, 1910, http://chessforallages.blogspot.com/2007/01/most-infamous-world-championship-game.html, retrieved on 2008-05-30

- ↑ Walter Preiswerk (20 February 1910), "(title unknown)", Basler Nachrichten, http://www.chesshistory.com/winter/winter19.html#4142._Lord_Dunsany_and_chess_C.N._4141, retrieved on 2008-07-10 - scroll down to Chess Note 4144 "Lasker v Schlechter"

- ↑ Raymond Keene. "Was Schlechter Robbed?". Retrieved on 2008-05-30.

- ↑ Using average incomes as the conversion factor; if prices are used for the conversion, the result is about $45,000 - see "Six Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount, 1774 to Present". Retrieved on 2008-06-05.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 1921 World Chess Championship This cites: a report of Lasker's concerns about the location and duration of the match, in , New York Evening Post, March 15, 1911; Capablanca's letter of December 20, 1911 to Lasker, stating his objections to Lasker's proposal; Lasker's letter to Capablanca, breaking off negotiations; Lasker's letter of April 27, 1921 to Alberto Ponce of the Havana Chess Club, proposing to resign the 1921 match; and Ponce's reply, accepting the resignation.

- ↑ "Chessmetrics Player Profile: Akiba Rubinstein". Retrieved on 2008-06-04.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 "I matches 1915/29". Retrieved on 2008-05-29.

- ↑ "Berlin 1897, 1918 and 1928". Retrieved on 2008-06-05.

- ↑ Lasker wrote "I who vanquished him must see to it that his great achievement, his theories should find justice, and I must avenge the wrongs he suffered" - Emanuel Lasker (1925, reprinted 1960). accessdate=2008-05-31 Lasker's Manual of Chess. Dover. ISBN 486-20640-8. http://www.mark-weeks.com/chess/z4ls$wix.htm accessdate=2008-05-31.

- ↑ Emanuel Lasker (January 1905). "From the Editorial Chair". Lasker's Chess Magazine 1. http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Lasker's_Chess_Magazine/Volume_1. Retrieved on 2008-05-31.

- ↑ Lasker, Emanuel (August 1895). "Metrical Relations of Plane Spaces of n Manifoldness". Nature 52 (1345): 340–343. doi:. http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/052340d0. Retrieved on 2008-05-31. Lasker, Emanuel (October 1895). "About a certain Class of Curved Lines in Space of n Manifoldness". Nature 52 (1355): 596. doi:. http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/052596a0. Retrieved on 2008-05-31.

- ↑ Samuel Reshevsky (1976). Great Chess Upsets. [[New York (city)|]]: Arco.

- ↑ Lasker, Emanuel (1901). "Über Reihen auf der Convergenzgrenze". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A 196: 431–477. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1901RSPTA.196..431L. Retrieved on 2008-05-31.

- ↑ Lasker, E. (1905), "Zur Theorie der Moduln und Ideale", Math. Ann. 60: 19–116, doi: Noether, Emmy (1921), "Idealtheorie in Ringbereichen", Mathematische Annalen 83 (1): 24, doi:, ISSN 0025-5831 For the relationship between Lasker's work and Noether's see "Springer Online Reference Works: Lasker ring". Retrieved on 2008-05-31.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 60.4 60.5 60.6 60.7 60.8 "Lasker: New Approaches". Retrieved on 2008-11-21.; also available at "Lasker: New Approaches" (PDF). Retrieved on 2008-05-02.. This refers to Ulrich Sieg and Michael Dreyer, ed. (2001). Emanuel Lasker: Schach, Philosophie und Wissenschaft (Emanuel Lasker: Chess, Philosophy and Science). Philo. ISBN 3825702162..

- ↑ Many sources say Kampf was published in 1907, but Lasker said 1906 - Emanuel Lasker (1932, re-printed 1960). Lasker's Manual of Chess. Courier Dover. ISBN 0486206408.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Leonard, J.. "Working Paper - New Light on von Neumann: politics, psychology and the creation of game theory" (PDF). Department of Economics, University of Turin. Retrieved on 2008-05-01.

- ↑ Emanuel Lasker (1896 (German edition); 1897, reprinted 1965 (English edition)). Common Sense in Chess. Courier Dover. ISBN 0486214400. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=1MP1FhWELmAC&dq=%22common+sense+in+chess%22+lasker&psp=1&source=gbs_summary_s&cad=0. Retrieved on 2008-05-02.

- ↑ "Chess World's Doings; Lasker to Test Rice Gambit". New York Times. August 2, 1903. http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?_r=1&res=9D03E7DD173AE733A25751C0A96E9C946297D6CF&oref=slogin. Retrieved on 2008-05-02.

- ↑ , Lasker’s Chess Magazine: p.35, November 1907, http://www.chesshistory.com/winter/winter29.html, retrieved on 2008-05-02

- ↑ "Moravian chess publishing - Catalogue". Retrieved on 2008-05-02.

- ↑ Laird, R. (2001), "Go in America", Seoul: Myong-Ji University, http://www.usgo.org/resources/downloads/goinamerica.pdf, retrieved on 2008-05-02

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 Edward Winter. "How Capablanca Became World Champion". Retrieved on 2008-06-05.. Winter cites: American Chess Bulletin (July-August 1920 issue) for Lasker's resignation of the title, the ACB’s theory about Lasker's real motive and Havana's offer of $20,000; Amos Burn in The Field of 3 July 1920, the British Chess Magazine of August 1920 and other sources for protestations that Lasker had no right to nominate a successor; Amos Burn in The Field of 3 July 1920 and E.S. Tinsley in The Times (London) of 26 June 1920 for criticism of the conditions Lasker set for the defense of the title; American Chess Bulletin September-October 1920 for Lasker's and Capablanca's statements that Capablanca was the champion and Lasker the challenger, for Capablanca's statement that Lasker's contract with Rubinstein had contained a clause allowing him to abdicate in favor of Rubinstein, for Lasker's intention to resign the title if he beat Capablanca and his support for an international organization, preferably based in the Americas, to manage international chess. Winter says that before Lasker's abdication some chess correspondents had been calling for Lasker to be stripped of the title. For a very detailed account given by Capablanca after the match, see José Raúl Capablanca (October 1922), , British Chess Magazine, http://www.chesshistory.com/winter/extra/capablancalasker.html, retrieved on 2008-06-05

- ↑ "I matches 1930/49". Retrieved on 2008-06-06.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 "I tornei di scacchi dal 1920 al 1929". Retrieved on 2008-05-29.

- ↑ "Production of Lasker trainer cancelled". Retrieved on 2008-05-02. includes an image of part of the original newspaper report.

- ↑ Emanuel Lasker (1927, 2nd edition 1932, reprinted 1960). Lasker's Manual of Chess. Dover. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=vNXFc-JWpH0C&dq=%22lasker%27s+manual+of+chess%22&pg=PP1&ots=J7OVyaSIjg&sig=x3WQXHRGFUEy4ewGhasPlCRacjY&hl=en&prev=http://www.google.co.uk/search%3Fhl%3Den%26q%3D%2522Lasker%2527s%2BManual%2Bof%2BChess%2522%26btnG%3DSearch&sa=X&oi=print&ct=title&cad=one-book-with-thumbnail. Retrieved on 2008-06-06.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Johan Wăstlund (September 5, 2005). "A solution of two-person single-suit whist" (PDF). The Electronic Journal of Combinatorics 12. http://www.emis.de/journals/EJC/Volume_12/PDF/v12i1r43.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-06-06.

- ↑ History of Go in Europe 1880-1945

- ↑ "About Lasca – a little-known abstract game". Retrieved on 2008-06-06.

- ↑ "Chess and Bridge". Retrieved on 2008-06-06.

- ↑ Morgan, D.J. (October 1975). . British Chess Magazine: 460. http://www.chesshistory.com/winter/extra/culbertson.html. Retrieved on 2008-11-21.

- ↑ Litmanowicz, Władysław & Giżycki, Jerzy (1986, 1987). Szachy od A do Z. Wydawnictwo Sport i Turystyka Warszawa. ISBN 83-217-2481-7 (1. A-M), ISBN 83-217-2745-x (2. N-Z).

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 "I tornei di scacchi dal 1930 al 1939". Retrieved on 2008-05-29.

- ↑ Reuben Fine (1965). Great Moments in Modern Chess. Dover. ISBN 0-486-21449-4.

- ↑ Soltis, A. (2005). Why Lasker Matters. Batsford. http://www.chesscenter.com/twic/jwatsonbkrev80.html. The URL is a review by John L. Watson

- ↑ "Lasker's greatest skill in defense was his ability to render a normal (inferior) position chaotic": Crouch, C. (2000). How to Defend in Chess. Everyman.; review including this quotation at Watson, J.. "How to Defend in Chess: review". Retrieved on 2008-11-19.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Kramnik, V.. "Kramnik Interview: From Steinitz to Kasparov". Vladmir Kramnik.

- ↑ Steve Wrinn. "Lasker and the Exchange Variation of the Ruy Lopez - Part 1" (PDF). Retrieved on 2008-06-09. and Steve Wrinn. "Lasker and the Exchange Variation of the Ruy Lopez - Part 2" (PDF). Retrieved on 2008-06-09.

- ↑ Prof. Nagesh Havanur). "Why Lasker Matters - review by Prof. Nagesh Havanur". Retrieved on 2008-11-21.

- ↑ Bobby Fischer, "The Ten Greatest Masters in History," Chessworld, Vol. 1, No. 1 (January-February 1964), pp. 56-61.

- ↑ Benko, Pal; Silman, Jeremy (2003). Pal Benko: My Life, Games and Compositions. Siles Press. pp. p.429.

- ↑ Keene, Raymond; Divinsky, Nathan (1989), Warriors of the Mind, Brighton, UK: Hardinge Simpole See the summary list at "All Time Rankings". Retrieved on 2008-11-21.

- ↑ Elo, A. (1978). The Rating of Chessplayers, Past and Present. Arco. ISBN 0668047216. http://www.chessbase.com/newsdetail.asp?newsid=1160. The URL provides greater detail, covering 47 players whom Elo rated, and notes that Bobby Fischer and Anatoly Karpov would have topped the list if the January 1 1978 FIDE ratings had been included - the FIDE ratings use Elo's system.

- ↑ "Peak Average Ratings: 1 year peak range". Retrieved on 2008-06-10. "Peak Average Ratings: 5 year peak range". Retrieved on 2008-06-10. "Peak Average Ratings: 10 year peak range". Retrieved on 2008-06-10. "Peak Average Ratings: 15 year peak range". Retrieved on 2008-06-10. "Peak Average Ratings: 20 year peak range". Retrieved on 2008-06-10.

- ↑ Sonas, J. (2005). "The Greatest Chess Player of All Time – Part IV". Chessbase. Retrieved on 2008-11-19. Part IV gives links to all 3 earlier parts.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 92.2 Michael Jeffreys). "Why Lasker Matters - review by Michael Jeffreys". Retrieved on 2008-06-10.

- ↑ ChessGames.com. "Euwe-Lasker Results". Retrieved on 2008-12-03.

- ↑ Fine, R. (1948). The Ideas behind the Chess Openings". Bell.

- ↑ "French Defense". Retrieved on 2008-06-10.

- ↑ Winter, E.. "Chess Note 4767 Copyright". Retrieved on 2008-06-25.

- ↑ Edward Winter. "Copyright on Chess Games". Retrieved on 2008-06-25.

- ↑ "Jose Raul Capablanca: Online Chess Tribute". chessmaniac.com (2007-06-28). Retrieved on 2008-05-20.

- ↑ "New York 1924". chessgames. Retrieved on 2008-05-20.

- ↑ Clayton, G.. "The Mad Aussie's Chess Trivia - Archive #3". Retrieved on 2008-06-09.

- ↑ Hannak, J. (2004). Emanuel Lasker: Chess Colossus. Hardinge Simpole. ISBN 1843821397. http://www.hardingesimpole.co.uk/biblio/1843821397.htm. Retrieved on 2008-11-21.

- ↑ Bill Wall. "Relatives of Chessplayers". Retrieved on 2008-11-21.

- ↑ Reprint of Edward Lasker's memoirs of the New York 1924 tournament, in , Chess Life, March 1974

- ↑ "New York 1924". Retrieved on 2008-11-21.

- ↑ " Emanuel Lasker's Manual of Chess is the most expressly philosophical chess book ever written" Shibut, M.. "Modern Chess Anarchy?". Retrieved on 2008-11-21.

- ↑ "London 1883 and 1899". Retrieved on 2008-05-29.

Further reading

- Kasparov, Garry (2003), My Great Predecessors, part I, Everyman Chess, ISBN 1-85744-330-6

- World chess champions by Edward G. Winter, editor. 19981 ISBN 0-08-024094-1

- J. Hannak, Emanuel Lasker: The Life of a Chess Master (1952, reprinted by Dover, 1991. Albert Einstein wrote the foreword to this book.). ISBN 0-486-26706-7

- Ken Whyld, The Collected Games of Emanuel Lasker (The Chess Player, 1998)

- Twelve Great Chess Players and Their Best Games by Irving Chernev; Dover; August 1995. ISBN 0-486-28674-6

- Why Lasker Matters, by Andrew Soltis, 2005, Batsford.

External links

- Emanuel Lasker at ChessGames.com

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Emanuel Lasker", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive

- The Game of Lasca

- Kmoch, Hans. [1]. Chesscafe.com.

- Another Lasker biography

- Lasker's Chess Magazine, January 1905 edition, excerpts

- Emanuel Lasker at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Jacobs, Joseph; Porter, A. (1901–1906), "Lasker, Emanuel", in Singer, Isidore, Jewish Encyclopedia, 7, pp. 622–3, http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=84&letter=L, retrieved on 2008-11-21

| Preceded by Wilhelm Steinitz |

World Chess Champion 1894–1921 |

Succeeded by José Raúl Capablanca |

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Lasker, Emanuel |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Lasker, Emanuel; Lasker, Emanuel |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | German chess World Chess Champion and grandmaster, mathematician, and philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 24, 1868 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Barlinek, Poland |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 11, 1941 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | New York City, United States |