Eleftherios Venizelos

|

Elefthérios Venizélos

(Greek: Ελευθέριος Βενιζέλος) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office 6 October, 1910 – 25 February, 1915 |

|

| Preceded by | Stephanos Dragoumis |

| Succeeded by | Dimitrios Gounaris |

| In office 10 August, 1915 – 24 September, 1915 |

|

| Preceded by | Dimitrios Gounaris |

| Succeeded by | Alexandros Zaimis |

| In office 14 June, 1917 – 4 November, 1920 |

|

| Preceded by | Alexandros Zaimis |

| Succeeded by | Dimitrios Rallis |

| In office 11 January, 1924 – 6 February, 1924 |

|

| Preceded by | Stylianos Gonatas |

| Succeeded by | Georgios Kafantaris |

| In office 4 July, 1928 – 26 May, 1932 |

|

| Preceded by | Alexandros Zaimis |

| Succeeded by | Alexandros Papanastasiou |

| In office 5 June, 1932 – 4 November, 1932 |

|

| Preceded by | Alexandros Papanastasiou |

| Succeeded by | Panagis Tsaldaris |

| In office 16 January, 1933 – 6 March, 1933 |

|

| Preceded by | Panagis Tsaldaris |

| Succeeded by | Alexandros Othonaios |

|

Prime Minister of the Cretan State

|

|

| In office 2 May, 1910 – 6 October, 1910 |

|

| Preceded by | Alexandros Zaimis (as High Commissioner) |

|

Minister of Justice and Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Cretan State

|

|

| In office 1908 – 1910 |

|

|

Minister of Justice of the Cretan State

|

|

| In office 17 April, 1899 – 18 March, 1901 |

|

|

|

|

| Born | 23 August 1864 |

| Died | 18 March 1936 (aged 71) |

| Nationality | Greek |

| Political party | Liberal Party |

| Spouse | Maria Katelouzou Elena Skylitsi |

| Children | Kyriakos Venizelos, Sophoklis Venizelos |

| Alma mater | National and Kapodistrian University of Athens |

| Profession | Lawyer, Journalist |

| Religion | Christian Orthodox |

| Signature | |

Eleftherios Venizelos (full name Elefthérios Kyriákou Venizélos, Greek: Ελευθέριος Κυριάκου Βενιζέλος) (Mournies Chania, 23 August 1864 - Paris, 18 March 1936) was an eminent Greek revolutionist, a prominent and illustrious statesman as well as a charismatic leader in the early 20th century.[1][2][3] Elected several times as Prime Minister of Greece and served from 1910 to 1920 and from 1928 to 1932. Venizelos had such profound influence on the internal and external affairs of Greece that he is credited with being "the maker of modern Greece".[4]

His first entry into the international scene was with his significant role in the autonomy of the Cretan State and later in the union of Crete with Greece. Soon, he was invited to Greece to resolve the political dead-lock and became the Prime Minister. He initiated not only constitutional and economic reforms to set the basis for the modernization of the Greek society, but also reorganized the army and navy for the subsequent conflicts. In the Balkan wars (1912–1913), Venizelos' catalytic role to Balkan League's creation (an alliance of the Balkan states against Turkey) and with his leadership, Greece doubled in area and population with the liberation of Macedonia, Epirus, and the rest of Aegean islands. In the World War I (1914–1918), he brought Greece on the side of the Allies, further expanding the Greek borders. However, with his foreign policies he came in direct conflict with the monarchy, causing the National Schism. The Schism polarized the population between the royalists and Venizelists (supporters of Venizelos) and the struggle for power between the two groups afflicted the political and social life of Greece for decades. Despite his achievements, Venizelos was defeated in the 1920 General Election, which later triggered the Greek defeat in the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922). In the subsequent periods in office, Venizelos succeeded in restoring normal relations with Greece's neighbors and expanded his constitutional, economical reforms. In 1935, Venizelos came out of retirement to support a military coup and its failure severely weakened the Second Hellenic Republic, the republic he had created.

Contents

|

Origins and early years

Ancestors

In the eighteenth century, the ancestors of Venizelos were surnamed Cravvatas and lived at Mistra (Sparta). During the Albanian invasion of the Peloponnesus, in 1770, one member of the Cravvatas family, Venizelos Cravvatas, the youngest of several brothers, managed to escape to Crete, where he established himself. His sons discarded their patronymic and called themselves Venizelos.[5]

Family and education

Eleftherios was born in Mournies, near Chania (also known as Canea) in then–Ottoman Crete to Kyriakos Venizelos, a Cretan revolutionary.[6] When the Cretan revolution of 1866 broke out, Venizelos' family fled to the island of Syros, due to the participation of his father in the revolution.[7] They were not allowed to return to Crete, and stayed in Syros until 1872, when Abdülaziz granted an amnesty.

He spent his final year of secondary education at a school in Ermoupolis in Syros from which he received his Certificate in 1880. In 1881, he enrolled at the Law School of the University of Athens and got his degree in Law with excellent grades. He returned in Crete in 1886. There he worked as a lawyer in Chania. Throughout his life he had a passion for reading, and was constantly improving his skills in English, Italian, German and French.[5]

Entry into politics

The situation in Crete during Venizelos' early years was fluid. The Turkish government was undermining the reforms, which were made under international pressure, while the Cretans desired to see the Sultan, Abdul Hamid II, abandoning "the ungrateful infidels".[8] Under these unstable conditions, Venizelos entered into politics in the elections of 2 April, 1889 as a member of the island's liberal party.[6] As a deputy, he was distinguished for his eloquence and his radical opinions.[9]

Political career in Crete

The Cretan uprising

- See also: History of Crete

Background

The numerous revolutions in Crete, during and after the Greek War of Independence, (1821, 1833, 1841, 1858, 1866, 1878, 1889, 1895, 1897)[10] were the result of the Cretans' desire for Enosis — Union with Greece.[11] In the Cretan revolution of 1866, the two sides, under the pressure of the Great Powers, came to an agreement, which was finalized in the Pact of Chalepa. Later the Pact was included in the provisions of the Treaty of Berlin, which was supplementing previous concessions granted to the Cretans — e.g. the Organic Law Constitution (1868) designed by William James Stillman. In summary the Pact was granting a large degree of self-government to Greeks in Crete as a means of limiting their desire to rise up against their Ottoman overlords.[12] However, the Muslims of Crete, who identified with Ottoman Turkey, were not satisfied by these reforms, as in their view the administration was delivered to the hands of the Christian Greek inhabitants of the island. In practice, the Ottoman Empire failed to enforce the provisions of the Pact, thus fueling the tensions between the two communities; instead, the Ottoman authorities attempted to maintain order by the dispatching of substantial military reinforcements in the 1880–1896 period. Throughout that period, the Cretan Question was a major issue of friction in the relations of independent Greece with the Ottoman Empire.

In January 1897, violence and disorder was escalating on the island, thus polarizing the population. Massacres against the Christian population took place in Chania[13][14][15][16] and Rethimno.[16][17][18] The Greek government, pressured by public opinion, intransigent political elements, extreme nationalist groups, Ethniki Etairia[19], and the Great Powers reluctant to intervene, decided to send warships and personnel to assist the Cretan Greeks.[20] The Great Powers had no option then but to proceed with the occupation of the island, but they were late. A Greek force of about 2,000 men had landed at Kolymbari on 3 February, 1897,[21] and its commanding officer, Colonel Timoleon Vassos declared that he was taking over the island "in the name of the King of the Hellenes" and that he was announcing the union of Crete with Greece.[22] This led to an uprising that spread immediately throughout the island. The Great Powers decided with their fleets to blockade Crete and land their troops, thus stopping the Greek army force from approaching Chania.[23]

The events at Akrotiri

Venizelos, at that time, was in a electoral tour of the island. Once, he "saw Canea in flames",[24] he hurried to Malaxa, near Chania, where a group of about 2,000 rebels had assembled, and established himself as their header. He proposed an attack, along with other rebels, on the Turkish forces at Akrotiri in order to displace them from the plains (Malaxa is in a higher altitude). Venizelos' subsequent actions at Akrotiri form a central set-piece in his myth. People composed poems on Akrotiri and his role there; editorials and articles spoke about his bravery, his visions and his diplomatic genius as inevitable accompaniment of later greatness.[13] Venizelos spent the night in Akrotiri and a Greek flag was raised. The Turkish forces requested help from the foreign admirals and attacked the rebels, thus the ships of the Great Powers bombarded the rebel positions at Akrotiri. A shell threw down the flag, which was raised up again immediately. The mythologizing became more pronounced when we come to his actions in that February, as the following quotes display:

| “ | On 20th of February [he] was ordered by the admirals to lower the flag and disband his rebel force. He refused![25] | ” |

| “ | Venizelos turned towards to the port of Souda, where the warships were anchored and explained: "You have cannon-balls - fire away! But our flag will not come down"... [after the flag was hit] Venizelos ran forward; his friends stopped him; why expose a valuable life so uselessly?[26] | ” |

| “ | There was that famous day in February 1897 when... he rejected the orders of the Protecting Powers and in the picturesque phrase in the Greek newspapers "defied the navies of Europe"[27] | ” |

| “ | Under the smooth diplomat of today is the revolutionist who prodded the Turks out of Crete and the bold chieftain who camped with a little band of rebels on a hilltop above Canea and there he defied the consuls and the fleets of all the [Great] Powers![28] | ” |

In the same evening of the bombardment, Venizelos wrote a protest to the foreign admirals, which was signed by all the chieftains present at Akrotiri. He wrote that the rebels would keep their positions until everyone is killed from the shells of European warships, in order not to let the Turks remain in Crete.[29] The letter was deliberately leaked to the international press, evoking emotional reactions in Greece and in Europe, where the sight of Christians, who wanted their freedom and bombarded by Christian vessels, caused popular indignation. Throughout western Europe much popular sympathy for the cause of the Christians in Crete was manifested, and much popular applause was bestowed on the Greeks.[23]

The war in Thessaly

-

For more details on this topic, see Greco-Turkish War (1897).

The Great Powers sent a verbal note on 2 March to the governments of Greece and the Ottoman Empire, presenting a possible solution to the "Cretan Question", under which Crete to become an autonomous state under the suzerainty of the Sultan.[8] The Porte replied on 5 March, accepting the proposals in principle, but on 8 March the Greek government rejected the proposal as a non-satisfactory solution and instead insisted on the union of Crete with Greece as the only solution.

Venizelos, as a representative of the Cretan rebels, met the admirals of the Great Powers on a Russian warship on 7 March 1897. Even though no progress was made at the meeting, he persuaded the admirals to send him on a tour of the island, under their protection, in order to explore the people's opinions on the question of autonomy versus union.[30] At the time, the majority of the Cretan population initially supported the union, but the subsequent events in Thessaly turned the public opinion towards autonomy as an intermediate step.

In reaction to the rebellion of Crete and the assistance sent by Greece, the Ottomans had relocated a significant part of their army in the Balkans to the north of Thessaly, close to the borders with Greece.[31] Greece in reply reinforced its borders in Thessaly. However, irregular Greek forces, who were members of the Ethniki Etairia (followers of the Megali Idea) acted without orders and raided Turkish outposts,[32] leading the Ottoman Empire to declare war on Greece on 17 April. The war was a disaster for Greece. The Turkish army was better prepared, in large part due to the recent reforms carried out by a German mission under Baron von der Goltz, and the Greek army was in retreat within weeks. The Great Powers again intervened and an armistice was signed in May 1897.[33]

Conclusion

The humiliating defeat of Greece in the Greco-Turkish war, costing small territorial losses at the border line in northern Thessaly and an indemnity of £4,000,000,[33] turned into a diplomatic victory. The Great Powers (Britain, France, Russia, and Italy), following the massacre in Heraklion on 25 August,[16][34][35] imposed a final solution on the "Cretan Question"; Crete was proclaimed an autonomous state under Ottoman suzerainty.

Venizelos played an important role towards this solution, not only as the leader of the Cretan rebels but also as a skilled diplomat with his frequent communication with the admirals of the Great Powers.[35] The four Great Powers assumed the administration of Crete; and Prince George of Greece, the second son of King George I of Greece, became High Commissioner, with Venizelos serving as his minister of Justice from 1899 to 1901.[36]

Autonomous Cretan State

- See also: Cretan State

Prince George was appointed High Commissioner of the Cretan State for a three-year term.[36] On 13 December, 1898, he arrived at Chania, where he received an unprecedented reception. On 27 April, 1899, the High Commissioner created an Executive Committee composed of the Cretan leaders. Venizelos became minister of Justice and with the rest of the Committee, they began to organize the State. After Venizelos submitted the complete juridical legislation on 18 May, 1900, disagreements between him and Prince George began to emerge.

Prince George decided to travel to Europe and announced to the Cretan population that "When I am traveling in Europe I shall ask the Powers for annexation, and I hope to succeed on account of my family connections".[37] The statement reached the public without the knowledge or approval of the Committee. Venizelos said to the Prince that it would not be proper to give hope to the population for something that wasn't feasible at the given moment. As Venizelos had expected, during the Prince's journey, the Great Powers rejected his request.[36][37]

The disagreements continued on other topics; the Prince wanted to build a palace, but Venizelos strongly opposed it as that would mean perpetuation of the current arrangement of Governorship; Cretans accepted it only as temporary, until a final solution was found.[36] Relations between the two men became increasingly soured, and Venizelos repeatedly submitted his resignation.[38]

In a meeting of the Executive Committee, Venizelos expressed his opinion that the island was not in essence autonomous, since militarily forces of the Great Powers were still present, and that the Great Powers were governing thought their representative, the Prince. Venizelos suggested that once the Prince's service expired, then the Great Powers should be invited to the Committee, which, according to article 39 of the constitution (which was suppressed in the conference of Rome) would elect a new sovereign, thereby removing the need for the presence of the Great Powers. Once the Great Powers' troops left the island along with the their representatives, then the union with Greece would be easier to achieve. This proposal was exploited by Venizelos' opponents, who accused him that he wanted Crete as an autonomous hegemony. Venizelos replied to the accusations by submitting once again his resignation, with the reasoning that for him it would be impossible henceforth to collaborate with the Committee's members; he assured the Commissioner however that he did not intend to join the opposition.[36]

On 6 March, 1901, in a report, he exposed the reasons that compelled him to resign to the High Commissioner, which was however leaked to the press. On 20 March, Venizelos was dismissed, because "he, without any authorization, publicly supported opinions opposite of those of the Commissioner".[36][39] Henceforth, Venizelos assumed the leadership of the opposition to the Prince. For the next three years, he carried out a hard political conflict, until the administration was virtually paralyzed and tensions dominated the island. Inevitably, these events led in March 1905 to the Theriso Revolution, whose leader he was.

Revolution of Theriso

On 10 March, 1905, the rebels gathered in Theriso and declared "the political union of Crete with Greece as a single free constitutional state";[40] the resolution was given to the Great Powers, where it was arguing that the illegitimate transient arrangement was preventing the island's economic growth and the only natural solution to the Cretan Question was the union with Greece. The High Commissioner with the approval of the Great Powers replied to the rebels that they would use military force to impose their decisions.[36] However, more deputies joined with Venizelos, in Theriso. The Great Powers' consuls met with Venizelos in Mournies, in an attempt to achieve an agreement, but without any results.

The revolutionary government asked that Crete to be granted a regime similar with that of Eastern Rumelia. On 18 July, the Great Powers declared military law, but it did not discourage the rebels. On 15 August, the regular assembly in Chania voted most from the reforms that Venizelos proposed. The Great Powers' consuls met Venizelos in a new meeting and they accepted the reforms Venizelos had proposed. This led to the end of the revolution of Theriso and to the resignation of Prince George as the High Commissioner. The Great Powers assigned to the king of Greece, George I, the election of a new Commissioner. An ex-Prime Minister of Greece, Alexandros Zaimis, was chosen for the place of High Commissioner, and it was allowed for Greek officers and non-commissioned officers to undertake the organization of the Cretan Constabulary. As soon as the Constabulary was organized, the foreigner troops began to withdraw from the island. This was also a personal victory for Venizelos who as a result became known throughout Greece and even throughout Europe.[36]

Bulgaria gained its independence from the Ottoman Empire on 5 October, 1908, and one day later Franz Joseph Emperor of Austria announced the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina. The Cretans, burst out a new revolution in the island. Thousands citizens in Chania and the surrounding regions on that day formed a rally, in which Venizelos declared the union of Crete with the Greece. Having communicated with the government of Athens, Zaimis left to Athens before the rally.

An assembly was convened and it declared the independence of Crete, the civil servants were put under oath faith in the name of the king George I of Greece, while a fivefold Executive Committee was created with the command to control the island for the king George I of Greece and according to the laws of Greek state. Chairman of committee was the Michelidakis and Venizelos became minister of Justice and Foreign Affairs. In April 1910 new assembly was convened, and Venizelos was elected chairman and then became Prime Minister. All the foreigner troops left from Crete and the power transferred entirely to Venizelos' government.[41]

Political Career in Greece

Goudi military revolution of 1909

-

For more details on this topic, see Goudi coup and Military League.

In May 1909, a number of officers in the Greek army emulating the Young Turk Committee of Union and Progress, sought to reform their country's national government and reorganize the army, thus creating the Military League. The League, in August 1909, camped in the Athenian suburb of Goudi with their supporters forcing the Dimitrios Rallis' government to resign and a new one was formed with Kiriakoulis Mavromichalis. An inaugurating period of direct military pressure upon the Chamber followed, but the initial public support to the League quickly evaporated when it became apparent that the officers did not know how to implement their demands.[42] The political dead-end remained till the League invited Venizelos from Crete to undertake the leadership.[43]

Venizelos went to Athens and after consulting with the Military League and with representatives of the political world, proposed a new government and Parliament's reformation. His proposals were considered, by the King and Greek politicians as dangerous for the political regime. However, King George I, fearing the escalation of the crisis, convened a council with political leaders, and recommended them to accept Venizelos' proposals. The King, after a lot of postponements, he agreed to assign Stephanos Dragoumis (Venizelos' indication) for forming a new government, which would lead the country to elections once the League was disbanded.[44] In the elections of 8 August, 1910, almost half the seats in the parliament were won by Independents, who were newcomers to the Greek political scene. Venizelos despite doubts as to the validity of his Greek citizenship, and without having campaigned in person finished top at the electoral list in Attica. He was immediately recognized as the leader of the independents and thus he founded the political party, Komma Fileleftheron (Liberal Party). Soon after his election he decided to call for new elections in hope of winning an absolute majority. The old parties boycotted the new election in protest, and on 28 November 1910, Venizelos' party won 300 seats out of 362, most of which were new in the political scene.[42] Venizelos formed a government and started to reorganize the economic, political, and national affairs of the country.

The reforms in 1910-1914

Venizelos tried to advance his reform program in the realms of political and social ideologies, of education, and literature, by adopting practically viable compromises between often conflicting tendencies. In education, for example, the dynamic current in favor of the use of the popular spoken language, dimotiki, provoked conservative reactions, which led to the constitutionally embedded decision (Article 107) in favor of a formal "purified" language, katharevousa which looked back to classical precedents.[45]

On 20 May, 1911, a revision of the Constitution was completed, which focussed on the strengthening of individual freedoms, the introduction of measures to facilitate the legislative work of the Parliament, the establishment of obligatory elementary education, the legal right for compulsory expropriation, the safeguarding of the permanence of civil servants, the right to invite foreign personnel to undertake the reorganization of the administration and the armed forces, the re-establishment of the State Council and the simplification of the procedures for the reform of the Constitution. The aim of the reform program was the consolidation of public security and the rule of law as well as the development of the wealth-producing potential of the country. In this context, the long planned "eighth" Ministry, the Ministry of National Economy, assumed a leading role. This Ministry, from the time of its creation at the beginning of 1911, was headed by Emmanuel Benakis, a wealthy Greek merchant from Egypt and friend of Venizelos.[45] Between 1911 and 1912 a number of laws aiming to initiate labor legislation in Greece were promulgated. Particular measures against child labor and night-shift work for women, and regulated the hours of the working week and Sunday closing, and provided for labor organizations.[46] Venizelos also took measures for the improvement of management, of justice and security and for the settlement of the landless peasants of Thessaly.[45]

The Balkan Wars

-

For more details on this topic, see Balkan Wars.

Background

At the time there were diplomatic contacts with Turks to initiate reforms in Macedonia and in Thrace, which at the time were under the control of Ottoman Empire, for improving the living conditions of the Christian populations. Failure of the reforms would leave the only option of removing Turkey from the Balkans, an option that most Balkan countries shared. This last option appeared feasible to Venizelos, because Turkey was under a constitutional transition and its administrative mechanism was disorganized and weakened.[47] Also, there was no fleet capable to transport forces from Asia Minor to Europe, while the Greek fleet was dominating the Aegean Sea. Venizelos did not want to make any immediate major movements in the Balkans, until the Greek army and navy were reorganized (an effort that had begun from the last government of Georgios Theotokis) and the Greek economy is recovered.[48] Hence, Venizelos proposed to Turkey to recognize the Cretans the right to send deputies to the Greek Parliament, for closing the Cretan Question. However, the Young Turks (feeling confident after the Greco-Turkish war in 1897) threatened that they will make a military walk to Athens, if the Greeks insisted to such claims.

Balkan League

-

For more details on this topic, see Balkan League.

Venizelos, seeing no improvements coming after his approach with the Turks concerning the Cretan Question and at the same time not wanting to see Greece remaining inactive as it happened in the Russo-Turkish War in 1877 (where Greece's neutrality left the country out of the peace talks), he decided that the only way to settle the disputes with Turkey, was to join with the other Balkan counties, Serbia, Bulgaria and Montenegro, in an alliance known as Balkan League. Crown Prince Constantine was sent to represent Greece in a royal feast in Sofia, and Bulgarian students were invited in Athens, in 1911.[49] These events had a positive impact and on 30 May, 1912 Greece and Bulgaria signed a treaty. It provided mutual support in case of attack on either country by Turkey. The negotiations with Serbia, which Venizelos initiated for a similar agreement, were concluded in early 1913,[50] before that there were only oral agreements.[51]

Montenegro opened hostilities by declaring war on Turkey on 8 October, 1912. On 18 September, 1912, Greece along with her Balkan allies, declared the war on Turkey, thus joining into the First Balkan war.[50] On 1 October, in a regular session of the Parliament Venizelos announced the declaration of war to Turkey and accepting the Cretan deputies, thus closing the Cretan Question, with the declaration of the union of Crete with Greece. The Greek population received these developments with a big enthusiasm.

First Balkan War

-

For more details on this topic, see First Balkan War.

The army, with the Constantine in command, marched to Macedonia, achieving many victories. This period was marked by Venizelos' well-known disagreement with Constantine, concerning the course of the army should follow and which cities should be liberated first. After the victory of the Greek army at Sarantaporo, Venizelos intervened and insisted that Thessaloniki, which was a major and strategic port in the surrounding area, must be taken at all costs. Venizelos not only sent the following telegraph to General Staff saying:

| “ | Salonique à tout prix![52] | ” |

but also he kept frequent communication with the King for preventing the Prince marching north, towards Monastir.[52] Venizelos' opinion prevailed and on 26 October, 1912, the Greek army entered Thessaloniki, shortly ahead of the Bulgarians.[53] The Cretan Gendarmerie was ordered to be transferred to Thessaloniki and maintain order in the city. Indeed, in the city of Thessaloniki the largest single element in the city's population comprised Sephardic Jews, the descendants of the Jews expelled from Spain in 1492, who continued to speak Ladino, a mix of Spanish, Hebrew and other languages . Elsewhere in New Greece, as the recently acquired territories came to be known, there were substantial Slavic, Muslim (mainly Turkish), Vlach, and Gypsy populations.[54][55] Like the Jews, many of these populations did not look upon the Greeks as liberators.[55]

Once the campaign in Macedonia was complete, however, a large part of the Greek army under the Crown Prince was redeployed to Epirus, and in the Battle of Bizani the Ottoman positions were overcome and Ioannina taken on 22 February, 1913.[55] Meanwhile the Greek navy rapidly occupied the Aegean islands still under Ottoman rule, while it prevented the Turks bringing reinforcements to Balkans.[56][57]

On 20 November, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria signed truce with Turkey. It followed a conference in London, where Greece took part, even though the Greek army continued its enterprises in the area. The conference led to the Treaty of London between the allies and Turkey.

Second Balkan War

-

For more details on this topic, see Second Balkan War.

Nevertheless, the Bulgarians wanted to become the hegemonic force in the Balkans and made excessive claims, while Serbia asked for more territory than it had initially agreed to with the Bulgarians, citing to the additional help it had provided for Bulgaria in Thrace. Bulgarians also laid claims on Thessaloniki, since they wanted access to Mediterranean waters. In the conference of London, Venizelos clarified to the Bulgarians that Thessaloniki belonged to Greece, mainly by citing the fact that it was captured first by the Greek army.[58]

The rupture between the allies due to the Bulgarian claims was inevitable, and Bulgaria found itself standing against Greece and Serbia. On 19 May 1913, a pact of alliance was signed in Thessaloniki between Greece and Serbia. On 19 June the Second Balkan War began with a surprise Bulgarian assault against Serbian and Greek positions.[59] Constantine, now King after his father's assassination in March,[60] neutralized the Bulgarian forces in Thessaloniki and pushed the Bulgarian army further back with a series of hard-fought victories. Bulgaria was overwhelmed by the Greek and Serbian armies, while in the north the Romanian army was marching towards Sofia; the Bulgarians asked for truce. Venizelos went to Hadji-Beylik, where the Greek headquarters were, to confer with Constantine on the Greek territorial claims in the peace conference. Thus he went to Bucharest, where a peace conference was assembled. On 28 June 1913 a peace treaty was signed with Greece, Montenegro, Serbia and Romania on one side and Bulgaria on the other. Thus, after two successful wars, Greece had doubled its territory by gaining most of Macedonia, Epirus, Crete and the rest of the Aegean islands,[61] although the status of the latter remained as yet undetermined and a cause of tension with the Ottomans.

World War I and Greece

- See also: World War I, and Balkans Campaign (World War I)

Dispute over Greece's role in World War I

World War I started in the autumn of 1914, soon after the end of the Balkan Wars, and up to 1915, Greece remained neutral. Venizelos supported an alliance with the Entente, not only believing that Britain and France would win, but also it was the only choice for Greece, due to combination of the strong Anglo-French naval control of the Mediterranean and the geographical distribution of the Greek population, could have ill effects in the case of a naval blockade, as he characteristically remarked:

| “ | One cannot kick against geography![62] | ” |

On the other hand, Constantine favored the Central Powers and wanted Greece to remain neutral.[63] He was influenced both by his belief in the military superiority of Germany and also by his German wife, Queen Sophia, and his pro-German court. He therefore strove to secure a neutrality which would be favorable to Germany and Austria.[64]

In 1915, Winston Churchill (then First Lord of the Admiralty) suggested to Greece to take action in Dardanelles on behalf of the allies.[65] Venizelos saw this as an opportunity to bring the country on the side of the Entente in the conflict. However the King disagreed and Venizelos submitted his resignation on 21 February, 1915.[64] Venizelos' party won the elections and formed a new government.

The National Schism

- See also: Venizelism

Even though Venizelos promised to remain neutral, after the elections of 1915, Bulgaria's attack on Serbia, with which Greece had a treaty of alliance, obliged him to abandon that policy. The dispute between Venizelos and the King reached its height shortly after and the King invoked the Greek constitutional provision that gave the monarch the right to dismiss a government unilaterally. Meanwhile, using the excuse of saving Serbia, in October 1915, the Entente disembarked an army in Thessaloniki.[66]

The dispute continued between the two men, and in December 1915 Constantine forced Venizelos to resign for a second time and dissolved the Liberal-dominated parliament, calling for new elections. Venizelos left Athens and moved back to Crete. Venizelos did not take part in the elections, as he considered the dissolution of Parliament unconstitutional.[67][68]

On 16 August 1916, there was a rally in Athens, where with the support of the allied army, which had landed in Thessaloniki under the command of General Maurice Sarrail, Venizelos announced to the public his complete disagreement with Crown's policies. This had the effect to polarize the population between the royalists (also known as anti-Venezelists), who supported the crown, and Venizelists, who supported Venizelos. On 30 August, 1916, Venizelist army officers organized a military coup in Thessaloniki, and proclaimed the "Provisional Government of National Defence". There they founded a separate "provisional state" including Northern Greece, Crete and the Aegean Islands, with the support of the Entente.[69] Significantly, these areas comprised the "New Lands" won during the Balkan Wars, and where Venizelos enjoyed broad support, while "Old Greece" remained under the control of the royalist Athens government. The National Defence government quickly declared war on the Central Powers and set about assembling an army for the Macedonian front.

Towards the end of 1916, France and Britain, after failing to persuade the royalist government of Alexandros Zaimis to enter the war, officially recognized the National Defence government as the lawful government of Greece. Moreover they decided to remove King Constantine and place his second son Alexander on the throne of Greece. After a naval blockade to major coastal Greek cities and threats of bombardment of Athens by the Entente's ships, King Constantine accepted a self-exile to Switzerland on 11 June, 1917.[70][71] His departure was followed by the deportation of many prominent royalists, especially officers such as Ioannis Metaxas, to exile in France and Italy.

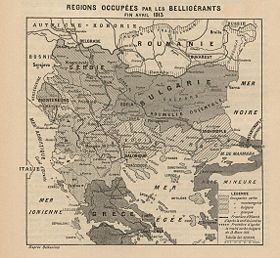

Greece enters World War I

On 29 May 1917, after the exile of Constantine to Switzerland and the ascension of Alexander, Venizelos returned to Athens; he allied with the Entente and declared war on the Central Powers. The entire Greek army was mobilized (though tensions remained between supporters of the monarchy and supporters of Venizelos) and began to take part in military operations against the Bulgarian army on the border. By the fall of 1918, the Greek army, with nine divisions, was the largest single national component of the Allied army in the Macedonian front.

Under the command of French General Franchet d'Esperey, a combined French, Serbian, Greek and British force launched a major offensive against the Bulgarian and German army, starting on 14 September 1918. The Bulgarians quickly gave up their defensive positions and began retreating back towards their country. On 24 September, the Bulgarian government asked for an armistice, which was signed five days later. The Allied army then attacked north and defeated the German and Austrian forces that tried to halt this offensive. By October 1918, the Allied armies had recaptured all of Serbia and were preparing to invade Hungary proper. The offensive halted only because the Hungarian leadership offered to surrender in November 1918.

Even though the Greek army ended up playing a small role in one of the final campaigns of World War I, Greece earned a seat at the Paris Peace Conference.

Conclusion of World War I and the Treaty of Sèvres

- See also: Paris Peace Conference (1919)

Following the conclusion of World War I, Venizelos took part in the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 as Greece's chief representative. During his absence from Greece for almost two years, he acquired a reputation as an international statesman of considerable stature.[2][3] President Woodrow Wilson was said to have placed Venizelos first in point of personal ability among all delegates gathered in Paris to settle the terms of Peace.[72]

In July 1919, Venizelos reached agreement with the Italians on the cession of the Dodecanese, and secured an extension of the Greek area of occupation in the periphery of Smyrna. The Treaty of Neuilly with Bulgaria on 27 November 1919, and the Treaty of Sèvres with the Ottoman Empire on 10 August 1920, were triumphs both for Venizelos and for Greece.[2][73][74] As the result of these treaties, Greece acquired Western Thrace, Eastern Thrace, Smyrna, the Aegean islands Imvros, Tenedos and the Dodecanese except Rhodes.[73]

In spite of all this, fanaticism continued to create a deep rift between the opposing political parties and to impel them towards unacceptable actions. On his journey home on 12 August 1920, Venizelos survived an assassination attack by two royalist soldiers at the Gare de Lyon railway station in Paris.[75] This event provoked unrest in Greece, with Venizelist supporters engaging in acts of violence against known anti-Venizelists, and provided further fuel for the national division. The persecution of Venizelos' opponents reached a climax with the assassination of the idiosyncratic anti-Venizelist Ion Dragoumis[64] by paramilitary Venizelists on 13 August.[76] After his recovery, Venizelos returned to Greece, where he was welcomed as a hero, because he had liberated areas with Greek populations and the creation of a state stretching over "five seas and two continents".[64]

1920 electoral defeat and the Great Disaster

- See also: Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922) and Great Fire of Smyrna

King Alexander died of blood poisoning caused by a bite from a monkey, two months after the signing of the treaty, on 2 October 1920. His death, revived the constitutional question whether Greece should be a monarchy or a republic and it transformed the elections due in November into a contest between Venizelos and the return of the exiled king Constantine, Alexander's father. In the elections anti-Venizelists, most of them supporters of Constantine, secured 246 out of 370 seats.[77] The defeat came as a surprise to most people, and Venizelos failed even to be elected as an MP.[64] Venizelos himself attributed it to the war-weariness of the Greek people, that had been under arms with almost no intermission since 1912. While, Venizelists believed that the promise of demobilization and withdrawal from Asia Minor was the most potent weapon of opposition. Abuse of power by Venizelists in the period 1917–1920 and the prosecution of their adversaries were also a further cause for the people to vote the opposition.[78] Thus, on 6 December 1920, King Constantine was recalled by a plebiscite.[64] This caused great dissatisfaction not only to the newly liberated populations in Asia Minor, but also to the Great Powers who opposed the return of Constantine.[77] As a result of his defeat, Venizelos left for Paris, withdrawing from politics.[79]

Once the anti-Venizelists came to power it became apparent that they intended to continue the campaign in Asia Minor. However, the following actions influenced the subsequent course of the war. The dismissal of the pro-Venizelos military officers with war experience for political reasons,[77] and underestimating the capabilities of the Turkish army,[79] while Italy and France found the royal restoration useful pretext for making their peace with Mustafa Kemal (leader of the Turks). In April 1921, all Great Powers have declared their neutrality; Greece was the only continuing the war.[80] Kemal launched a massive attack on 26 August and the Greeks forces were routed to Smyrna, which later fell to the Turks in 8 September, 1922 (see Great Fire of Smyrna).[80]

Following the defeat of the Greek army by the Turks in 1922, and the subsequent armed insurrection, led by Colonels Nikolaos Plastiras and Stylianos Gonatas, King Constantine was dethroned (and succeeded by his eldest son, George), and six royalist leaders were executed.[3] Venizelos assumed the leadership of the Greek delegation that negotiated peace terms with the Turks. He signed the Treaty of Lausanne with Turkey on 24 July 1923. This had as an effect more than a million Greeks were expelled from Turkey (in exchange for 500,000 Muslims), and Greece was forced to yield eastern Thrace, Imbros and Tenedos to Turkey. This catastrophe marked the end of the Megali Idea. After a failed pro-royalist insurrection led by General Ioannis Metaxas forced King George II into exile, Venizelos returned to Greece and became prime minister once again. However, he left again in 1924 after quarreling with anti-monarchists.

During these absences from power, he translated Thucydides into modern Greek, although the translation and incomplete commentary were only published in 1940, after his death.

Return to power in 1928 and subsequent exile

In the elections held on 5 July 1928, Venizelos' party regained power and forced the government to hold new elections on 19 August of the same year; this time his party won 228 out of 250 places in Parliament. During this period Venizelos attempted to end Greece's diplomatic isolation by restoring normal relations with the country's neighbors. His efforts proved to be successful in the cases of the newly founded Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and Italy. First Venizelos concluded an agreement, on 23 September 1928, with Benito Mussolini in Rome, and then he started negotiations with Yugoslavia which resulted in a Treaty of Friendship signed on 27 March 1929. An additional protocol settled the status of the Yugoslav free trade zone of Thessaloniki in a way favorable to Greek interests.[81] Nevertheless, despite the co-ordinated British efforts under Arthur Henderson in 1930–1931, full reconciliation with Bulgaria was never achieved during his premiership.[82] Venizelos was also cautious towards Albania, and although bilateral relations remained at a good level, no initiative was taken by either side aiming at the final settlement of the unresolved issues (mainly related with the status of the Greek minority of South Albania).[83]

Venizelos' greatest achievement in foreign policy during this period was the reconciliation with Turkey. Venizelos had expressed his will to improve the bilateral Greek–Turkish relations even before his electoral victory, in a speech in Thessaloniki (July 23, 1928). Eleven days after the formation of his government, he sent letters to both the prime minister and the minister of foreign affairs of Turkey (Ismet Inonu and Tewfik Rushdi respectively), declaring that Greece had no territorial aspirations to the detriment of their country. Inonu's response was positive, and Italy was eager to help the two countries reach an agreement. Negotiations, however, stalled because of the difficult issue of the properties of the exchanged populations. Finally, the two sides concluded an agreement on April 30, 1930; on October 25, Venizelos visited Turkey and signed a treaty of friendship. Venizelos even forwarded Atatürk's name for the 1934 Nobel Peace Prize ,[84] highlighting the mutual respect between the two leaders.[85] The German Chancellor Hermann Müller described the Greek-Turkish rapprochement as the "greatest achievement seen in Europe since the end of the Great War". Nevertheless, Venizelos' initiative was criticized domestically not only by the opposition but also by members of his own party, representing the Greek refugees from Turkey. Venizelos was accused of making too many concessions on the issues of naval armaments and of the properties of the Greeks who were expelled from Turkey according to the Treaty of Lausanne.[86]

His domestic position was weakened, however, by the effects of the Great Depression in the early 1930s;[87] and in the elections of 1932 he was defeated by the People's Party under Panagis Tsaldaris. The political climate became more tense, and in 1933 Venizelos was the target of a second assassination attempt.[88] The pro-royalist tendencies of the new government led to two attempted Venizelist coup attempts by General Nikolaos Plastiras: one in 1933, and the other in 1935. The failure of the latter proved decisive for the future of the Second Hellenic Republic. After the coup's failure, Venizelos left Greece once more, while in Greece, trials and executions of prominent Venizelists were carried out, and he himself sentenced to death in absentia. The severely weakened Republic was abolished in another coup in October 1935 by General Georgios Kondylis and George II returned to the throne following a rigged referendum in November.[89]

Exile and death

Venizelos left for Paris, and on 12 March 1936 wrote his last letter, to Alexandros Zannas. He had a stroke on the morning of the 13th and five days later died at his flat at 22 rue Beaujon.[90] A crowd of supporters from the local Greek community in Paris accompanied his body to the railway station prior to its departure for Greece.

His body was taken by the destroyer Pavlos Kountouriotis to Chania, avoiding Athens so as not to cause unrest. He was subsequently buried in Akrotiri, Crete with much ceremony.

Personal life and family

In December 1891 Venizelos married Maria Katelouzou, daughter of Eleftherios Katelouzos. The newlyweds lived in the upper floor of the Chalepa house, while Venizelos' mother and his brother and sisters lived on the ground floor. There, they enjoyed the happy moments of their marriage, and there, also, their two children were born, Kyriakos in 1892 and Sophoklis in 1894. Their married life, however, was short and marked by misfortune. Maria died of post-puerperal fever in November 1894 after the birth of their second child, Sophoklis. Her death deeply affected Venizelos and as sign of his mourning, he grew his characteristic beard and mustache, which he retained for the rest of his life.[6]

In 1920, after his defeat in the November elections, he left for Paris in a self-imposed exile. In September 1921, twenty seven years after the death of his first wife Maria, he married in Highgate in London an exceedingly wealthy woman called Helena Schilizzi (or Skylitsi) and settled down in Paris in a flat at 22 rue Beaujon. He lived there until 1927, when he returned to Chania.[6]

Footnotes

- ↑ Kitromilides, 2006, p. 178

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 'Liberty Still Rules', TIME, Feb. 18, 1924

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Venizélos, Eleuthérios". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. (2008).

- ↑ Duffield J. W., The New York Times, October 30, 1921, Sunday, link

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Chester, 1921, p. 4

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Mitsotaki, Zoi (2008). "Venizelos the Cretan. His roots and his family". National Foundation Research.

- ↑ Chester, 1921, p. 4

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Ion, 1910, p. 277

- ↑ Kitromilides, 2006, p. 45, 47

- ↑ Kitromilides, 2006, p. 16

- ↑ Clogg, 2002, p. 65

- ↑ "Pact of Halepa". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. (2008).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Kitromilides, 2006, p. 58

- ↑ Lowell Sun (newspaper), 6/2/1897, p. 1

- ↑ Holland, 2006, p. 87

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Papadakis, Nikolaos E. (2008). "Eleftherios Venizelos His path between two revolutions 1889-1897". National Foundation Research.

- ↑ Holland, 2006, p. 91

- ↑ Chester, 1921, p. 35

- ↑ Chester, 1921, p. 34

- ↑ Kitromilides, 2006, p. 30

- ↑ Kitromilides, 2006, p. 62

- ↑ Kerofilias, 1915, p. 14

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Dunning, Jun. 1987, p. 367

- ↑ Chester, 1921, p. 35–36

- ↑ Gibbons, p. 24

- ↑ Kerofilias, 1915, p. 13–14

- ↑ Leeper, 1916, p. 183–184

- ↑ Anne O'Hare, McCormark, Venizelos the new Ulysses of Hellas, The New York Times Magazine, 2 September, p. 14

- ↑ Kitromilides, 2006, p. 63–64

- ↑ Kitromilides, 2006, p. 65

- ↑ Rose, 1897, p. 2-3

- ↑ Dunning, June 1897, p. 368

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Dunning Dec. 1897, p. 744

- ↑ Ion, 1910, p. 278

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Kitromilides, 2006, p. 68

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 36.5 36.6 36.7 Manousakis, George (2008). "Eleftherios Venizelos during the years of the High Commissionership of Prince George (1898-1906)". National Foundation Research.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Kerofilias, 1915, p. 30–31

- ↑ Kerofilias, 1915, p. 33

- ↑ Chester, 1921, p. 82

- ↑ Chester, 1921, p. 95

- ↑ Archontaki, Stefania (2008). "1906-1910, The Preparation and Emergence of Venizelos on the Greek Political Stage - Venizelos as Prime Minister". National Foundation Research.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Mazower, 1992, p. 886

- ↑ "Military League". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. (2008).

- ↑ Chester, 1921, p. 129–133

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Gardika-Katsiadaki, Eleni (2008). "Period 1910 - 1914". National Foundation Research.

- ↑ Kyriakou, 2002, p. 491–492

- ↑ Hall, 2000, p. 1–9

- ↑ Kitromilides, 2006, p. 141

- ↑ Chester, 1921, p. 150

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Kitromilides, 2006, p. 145

- ↑ Hall, 2000, p. 13

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Chester, 1921, p. 159–160

- ↑ Hall, 2000, p. 61–62

- ↑ Pentzopoulos, 2002, p. 28, 132

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 "History of Greece". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. (2008).

- ↑ Chester, 1921, p. 161–164

- ↑ Hall, 2000, p. 17

- ↑ Chester, 1921, p. 169

- ↑ "Bulgaria, The Balkan Wars". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. (2008).

- ↑ The Times (London) 19 March 1913 p.6

- ↑ Tucker, 1999, p. 107

- ↑ Seligman, 1920, p. 31

- ↑ "World War I - Greek Affairs". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. (2008).

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 64.3 64.4 64.5 Theodorakis, Emanouil; Manousakis George (2008). "First World War 1914–1918". National Foundation Research.

- ↑ Firstworldwar.com The Minor Powers During World War One - Greece

- ↑ "Constantine I". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. (2008).

- ↑ Chester, 1921, p. 271

- ↑ Kitromilides, 2006, p. 122

- ↑ Clogg, 2002, p. 87

- ↑ Chester, 1921, p. 295–304

- ↑ Land of Invasion, TIME, 4 Nov 1940

- ↑ Chester, 1921, p. 6

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Kitromilides, 2006, p. 165

- ↑ Chester, 1921, p. 320

- ↑ "Venizelos shot, twice wounded by Greeks in Paris", New York Times: 1, 13 August 1920, http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9F06E7DA1E31E433A25750C1A96E9C946195D6CF

- ↑ Kitromilides, 2006, p. 129

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 77.2 Clogg, 2002, p. 95

- ↑ Kitromilides, 2006, p. 131

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Theodorakis, Emanouil; Manousakis George (2008). "Period 1920 – 1922". National Foundation Research.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Clogg, 2002, p. 96

- ↑ Karamanlis, 1995, p. 55, 70

- ↑ Karamanlis, 1995, p. 144-146

- ↑ Karamanlis, 1995, p. 158-160

- ↑ Nobel Foundation. The Nomination Database for the Nobel Prize in Peace, 1901–1955.[1]

- ↑ Clogg, 2002, p. 107

- ↑ Karamanlis, 1995, p. 95-97

- ↑ Black, 1948, p. 94

- ↑ Clogg, 2002, p. 103

- ↑ Black, 1948, p. 93–96

- ↑ Manolikakis, 1985, p. 18-22; Hélène Veniselos, A l'ombre de Veniselos (Paris, 1955).

References

|

|

See also

- History of Modern Greece

- Megali Idea

- Venizelism

- George I of Greece

- Constantine I of Greece

- Ioannis Metaxas

- Greek plebiscite, 1974

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Stephanos Dragoumis |

Prime Minister of Greece 18 October 1910 - 10 March 1915 |

Succeeded by Dimitrios Gounaris |

| Preceded by Dimitrios Gounaris |

Prime Minister of Greece 23 August 1915 - 7 October 1915 |

Succeeded by Alexandros Zaimis |

| Preceded by Alexandros Zaimis |

Prime Minister of Greece 27 June, 1917 - 18 November 1920 |

Succeeded by Dimitrios Rallis |

| Preceded by Stylianos Gonatas |

Prime Minister of Greece 24 January 1924 - 19 February 1924 |

Succeeded by Georgios Kaphantaris |

| Preceded by Alexandros Zaimis |

Prime Minister of Greece 4 July 1928 - 26 May 1932 |

Succeeded by Alexandros Papanastasiou |

| Preceded by Alexandros Papanastasiou |

Prime Minister of Greece 5 June, 1932 - 3 November 1932 |

Succeeded by Panagis Tsaldaris |

| Preceded by Panagis Tsaldaris |

Prime Minister of Greece 16 January 1933 - 6 March 1933 |

Succeeded by Alexandros Othonaios |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by founded |

Komma Fileleftheron (Liberal Party) 1910–1936 |

Succeeded by Themistoklis Sophoulis |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||