Electrolysis

In chemistry and manufacturing, electrolysis is a method of separating chemically bonded elements and compounds by passing an electric current through them.

Contents |

History

- 1800 - William Nicholson and Johann Ritter decomposed water into hydrogen and oxygen.

- 1807 - Potassium permanganate was discovered by Sir Humphry Davy

Overviews

Electrolysis involves the passage of an electric current through an ionic substance that is either molten or dissolved in a suitable solvent, resulting in chemical reactions at the electrodes. In a cell being discharged, the positive electrode is called the cathode, and the negative electrode is the anode.[1] (In a cell being charged, the anode is positive and the cathode is negative.) To be useful for electrolysis, the electrodes need to be able to conduct electricity, and metal electrodes are generally used. Graphite electrodes and semiconductor electrodes are also used. An ionic compound, or a compound that reacts with the solvent to produce ions (such as an acid) is dissolved in an appropriate solvent, or an ionic compound is melted by heat. Then some free ions exist in the liquid. An electrical potential is applied between a pair of electrodes immersed in the liquid. Each electrode attracts ions that are of the opposite charge. Therefore, positively-charged ions (called cations) move towards the electron-emitting (negative) cathode, whereas negatively-charged ions (termed anions) move toward the positive anode. The energy required to separate the ions, and cause them to gather at the respective electrodes, is provided by an electrical power supply. At the electrodes, electrons are absorbed or released by the ions, forming a collection of the desired element or compound.

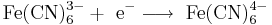

Oxidation of ions or neutral molecules can take place at the anode, and the reduction of ions or neutral molecules at the cathode. For example, it is possible to oxidize ferrous ions to ferric ions at the anode:

.

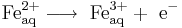

.

It is also possible to reduce ferricyanide ions to ferrocyanide ions at the cathode:

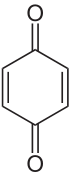

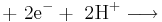

Neutral molecules can also react at either electrode. For example: p-Benzoquinone can be reduced to hydroquinone at the cathode:

In the last example,  ions (hydrogen ions) also take part in the reaction, and are provided by an acid in the solution, or the solvent itself (water, methanol etc). Electrolysis reactions involving

ions (hydrogen ions) also take part in the reaction, and are provided by an acid in the solution, or the solvent itself (water, methanol etc). Electrolysis reactions involving  ions are fairly common in acidic solutions. In alkaline solutions, reactions involving

ions are fairly common in acidic solutions. In alkaline solutions, reactions involving  (hydroxide ions) are common.

(hydroxide ions) are common.

The substances oxidised or reduced can also be the solvent (usually water) or the electrodes. It is possible to have electrolysis involving gases. For instance, fuel cells often use oxygen and hydrogen gases as reactants.

The amount of electrical energy that must be added equals the change in Gibbs free energy of the reaction plus the losses in the system. The losses can (in theory) be arbitrarily close to zero, so the maximum thermodynamic efficiency equals the enthalpy change divided by the free energy change of the reaction. In most cases, the electric input is larger than the enthalpy change of the reaction, so some energy is released in the form of heat. In some cases, for instance, in the electrolysis of steam into hydrogen and oxygen at high temperature, the opposite is true. Heat is absorbed from the surroundings, and the heating value of the produced hydrogen is higher than the electric input.

The following technologies are related to electrolysis:

- Electrochemical cells, including the hydrogen fuel cell, use the reverse of this process.

- Gel electrophoresis is an electrolysis wherein the solvent is a gel: It is used to separate substances, such as DNA strands, based on their electrical charge.

Electrolysis of water

One important use of electrolysis of water is to produce hydrogen.

- 2H2O(l) → 2H2(g) + O2(g)

This has been suggested as a way of shifting society toward using hydrogen as an energy carrier for powering electric motors and internal combustion engines. (See hydrogen economy.)

Electrolysis of water can be observed by passing direct current from a battery or other DC power supply through a cup of water (in practice a salt water solution increases the reaction intensity making it easier to observe). Using platinum electrodes, hydrogen gas will be seen to bubble up at the cathode, and oxygen will bubble at the anode. If other metals are used as the anode, there is a chance that the oxygen will react with the anode instead of being released as a gas, or that the anode will dissolve. For example, using iron electrodes in a sodium chloride solution electrolyte, iron oxides will be produced at the anode. With zinc electrodes in a sodium chloride electrolyte, the anode will dissolve, producing zinc ions (Zn2+) in the solution, and no oxygen will be formed. When producing large quantities of hydrogen, the use of reactive metal electrodes can significantly contaminate the electrolytic cell - which is why iron electrodes are not usually used for commercial electrolysis. Electrodes made of stainless steel can be used because they will not react with the oxygen.

The energy efficiency of water electrolysis varies widely. The efficiency is a measure of what fraction of electrical energy used is actually contained within the hydrogen. Some of the electrical energy is converted to heat, a useless by-product. Some reports quote efficiencies between 50% and 70%[1] This efficiency is based on the Lower Heating Value of Hydrogen. The Lower Heating Value of Hydrogen is total thermal energy released when hydrogen is combusted minus the latent heat of vaporisation of the water. This does not represent the total amount of energy within the hydrogen, hence the efficiency is lower than a more strict definition. Other reports quote the theoretical maximum efficiency of electrolysis as being between 80% and 94%.[2]. The theoretical maximum considers the total amount of energy absorbed by both the hydrogen and oxygen. These values refer only to the efficiency of converting electrical energy into hydrogen's chemical energy. The energy lost in generating the electricity is not included. For instance, when considering a power plant that converts the heat of nuclear reactions into hydrogen via electrolysis, the total efficiency is more likely to be between 25% and 40%.[3]

NREL found that a kilogram of hydrogen (roughly equivalent to a gallon of gasoline) could be produced by wind powered electrolysis for between $5.55 in the near term and $2.27 in the long term.[2]

About four percent of hydrogen gas produced worldwide is created by electrolysis, and normally used onsite. Hydrogen is used for the creation of ammonia for fertilizer via the Haber process, and converting heavy petroleum sources to lighter fractions via hydrocracking.

Experimenters

Scientific pioneers of electrolysis included:

- Antoine Lavoisier

- Humphry Davy

- Michael Faraday

- Paul Héroult

- Svante Arrhenius

- Adolph Wilhelm Hermann Kolbe

- William Nicholson

- Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac

- Alexander von Humboldt

- Johann Wilhelm Hittorf

Pioneers of batteries:

More recently, electrolysis of heavy water was performed by Fleischmann and Pons in their famous experiment, resulting in anomalous heat generation and the controversial claim of cold fusion.

Faraday's laws of electrolysis

First law of electrolysis

In 1832, Michael Faraday reported that the quantity of elements separated by passing an electrical current through a molten or dissolved salt is proportional to the quantity of electric charge passed through the circuit. This became the basis of the first law of electrolysis:

Second law of electrolysis

Faraday also discovered that the mass of the resulting separated elements is directly proportional to the atomic masses of the elements when an appropriate integral divisor is applied. This provided strong evidence that discrete particles of matter exist as parts of the atoms of elements.

Industrial uses

- Production of aluminium, lithium, sodium, potassium, magnesium

- Production of hydrogen for hydrogen cars and fuel cells; high-temperature electrolysis is also used for this

- Coulometric techniques can be used to determine the amount of matter transformed during electrolysis by measuring the amount of electricity required to perform the electrolysis

- Production of chlorine and sodium hydroxide

- Production of sodium chlorate and potassium chlorate

- Production of perfluorinated organic compounds such as trifluoroacetic acid

Electrolysis has many other uses:

- Electrometallurgy is the process of reduction of metals from metallic compounds to obtain the pure form of metal using electrolysis. For example, sodium hydroxide in its molten form is separated by electrolysis into sodium and oxygen, both of which have important chemical uses. (Water is produced at the same time.)

- Anodization is an electrolytic process that makes the surface of metals resistant to corrosion. For example, ships are saved from being corroded by oxygen in the water by this process. The process is also used to decorate surfaces.

- A battery works by the reverse process to electrolysis. Humphry Davy found that lithium acts as an electrolyte and provides electrical energy.

- Production of oxygen for spacecraft and nuclear submarines.

- Electroplating is used in layering metals to fortify them. Electroplating is used in many industries for functional or decorative purposes, as in vehicle bodies and nickel coins.

- Production of hydrogen for fuel, using a cheap source of electrical energy.[3]

- Electrolytic Etching of metal surfaces like tools or knives with a permanent mark or logo.

Electrolysis is also used in the cleaning and preservation of old artifacts. Because the process separates the non-metallic particles from the metallic ones, it is very useful for cleaning old coins and even larger objects.

See also

- Faraday's law of electrolysis

- The Faraday constant

- Gas cracker

- High pressure electrolysis

- Faraday Efficiency

- Electrolytic Cell

- Timeline of hydrogen technologies

References

- ↑ Science Probe 10, 1996, p 234

- ↑ Levene, J.; B. Kroposki, and G. Sverdrup (March 2006). "Wind Energy and Production of Hydrogen and Electricity - Opportunities for Renewable Hydrogen - Preprint" (PDF). National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Retrieved on 2008-10-20.

- ↑ 2008, hydrogen on demand fuel cells

|

||||||||||||||