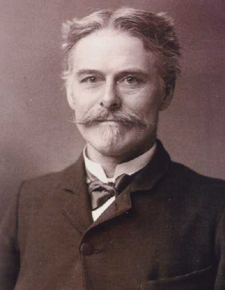

Edward Drinker Cope

| Edward Drinker Cope | |

|

|

| Born | July 28, 1840 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

|---|---|

| Died | April 12, 1897 (aged 56) |

| Nationality | American |

| Fields | Paleontology, zoology, herpetology |

| Religious stance | Quaker |

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840–April 12, 1897) was an American paleontologist and comparative anatomist, as well as a noted herpetologist and ichthyologist.

Born to a wealthy Quaker family, Cope quickly distinguished himself as a child prodigy interested in science; he published his first scientific paper in 1859. Cope married his cousin and had several children, moving closer to the marl pits of Haddonfield New Jersey to be near fossil finds.

Cope is best known for his highly publicized Bone Wars with O. C. Marsh. A race to publish their findings, and thus prioritize their discoveries, consumed both Marsh’s and Copes finances and lives. Cope traveled the American West searching for fossils. His staunch resolve in his belief of Neo-Lamarckism was the subject of ridicule by of many of his peers at the American Philosophical Society and by his greatest enemy, O.C. Marsh.

Along with his rival, Cope helped define the field of American paleontology. Cope's writing was prodigious, with a record 1,200 papers published over his lifetime. He named dozens of species of dinosaurs, and in total named more than 1,000 vertebrate species. His most established theories on the origin of mammalian molars and the Cope’s Law on the gradual enlargement of mammalian species are considered his best generalized theories.

Contents |

Biography

Early life

Edward Drinker Cope was born on July 28, 1840, the eldest son of Alfred and Hanna Cope.[1] The death of his mother at the age of three seemed to have little effect on him, as he mentioned in his letters that he had no recollection of her. His stepmother Rebecca Biddle filled the motherly role; Cope referred to her warmly, as well as his younger stepbrother, James Biddle Cope. His father was a philanthropist and gave money to the Advancement of Colored People, the Society of Friends, the education of Native Americans and the Philadelphia Zoological Gardens.

Edward was born and raised in a large stone house in present-day suburban Philadelphia, Pennsylvania called "Fairfield".[1] The eight acres of pristine and exotic gardens of the house offered a natural landscape that Edward was able to explore.[2] The Copes began teaching their children to read and write at a very young age, and took Edward on trips across New England and to museums, zoos, and gardens. Cope's interest in animals became apparent at a young age, as did his natural artistic ability.[3]

Alfred intended to give his son the same education that he himself was brought up in. At nine, Edward was sent to a day school in Philadelphia and in 1853 at the age of twelve, Edward was sent to the Friends’ Boarding School, near West Chester, Pennsylvania.[4] The school was founded in 1799 with fundraising by members of the Society of Friends (Quakers), as was the site of much of the Cope family's education.[5] The prestigious school was expensive, costing Alfred $500 tuition each year, and in his first year Edward studied Algebra, Chemistry, Scripture, Physiology, Grammar, Astronomy, and Latin.[6] Edward's letters home requesting a larger allowance show he was able to manipulate his father, and that he was, according to author Jane Davidson, "a bit of a spoiled brat".[7]

Despite complaints about his schooling, Cope returned to Westtown in 1855, accompanied by two of his sisters. Biology began to interest him more, and he studied natural history texts in his spare time. While at the prestigious school Cope frequently visited the Academy of Natural Sciences. Cope frequently obtained bad marks for quarrelsome and bad conduct, and his letters to his father show that he chafed at farm work and betrayed flashes of the temper he would later become well known for.[8] After sending Edward back to the farm for summer break in 1854 and 1855, Alfred did not return Edward to school after spring 1856. Instead Alfred attempted to turn his son into a gentleman farmer, a wholesome profession that would yield enough profit to lead a comfortable life. In his letters to his father, during this period till 1863, Edward continually yearned for more of a professional scientific career than that of a farmer, which he called, “dreadfully boring.”[9] His father went so far as to actually buy Edward a 200-acre (0.81 km2) farm in 1860.

While working on farms, Edward continued his education. In 1858 he began working at the Academy of Natural Sciences part-time, reclassifying and cataloguing specimens, and published his first series of research results in January 1859. Cope also began taking French and German classes with a former Westtown teacher.[10] Though Alfred resisted his son's acceptance of a science career, he also paid for his son's private studies.

Alfred finally gave into Edward’s strong intellectual capabilities and paid for classes. Cope attended the University of Pennsylvania in the 1861 and/or 1862 academic years,[11] studying comparative anatomy under Joseph Leidy, one of the most influential anatomists and paleontologists at the time.[12] Cope also asked his father to pay for a tutor in both German and French, "not so much for their own sake," wrote Edward, "but as for their value in enabling me to read their books of a literary or scientific character."[13] He also had a job during this period recataloging the herpetological collection at the Academy of Natural Sciences, in which he became a member at Leidy's urging.[14] Edward's job lasted two years and he visited the Smithsonian Institute on occasion while working. At the Smithsonian he became acquainted Spencer Baird, who was an expert in the field of ornithology and ichthyology.[15]

European travels

In 1863-1864, Edward traveled through Europe, taking the opportunity to visit all the most esteemed museums and societies of the time. His sudden departure for Europe prevented him from being drafted into the American Civil War; Edward was more concerned with helping the newly emancipated blacks in the south than the North’s need for his services in a hospital.[16] Another reason for the sudden departure was the failure of a love affair that deeply affected Edward, although Henry Fairfield Osborn’s biography barely mentions it. Edward's journals and letters from the time period do not exist, for he burned them upon his return from his European travels. Cope did write to his father from London on Feb. 11, 1864 that, “I shall get home in time to catch and be caught by the new draft. I shall not be sorry for this, as I know certain persons who would be mean enough to say that I have gone to Europe to avoid the war.”[17] The letters that his family kept from Edward show a deeply depressed man from his failed love affair. He attempted to "keep my resolution of occupying my mind constantly as to crowd out painful thoughts…..it is perhaps a great advantage that I have had the outside of my sensibilities scorched into a crust."[18]

Despite his torpor, Edward proceeded with his tour of Europe, and met with some of the most highly esteemed scientists of the world during his travels through France, Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, Austria, Italy, and Eastern Europe, most likely with introductory letters from Joseph Leidy and Spencer Baird.[19] In the winter of 1863, Edward met Othniel Charles Marsh while in Berlin, Germany. Marsh, aged thirty-two, was attending the University of Berlin. Though Marsh had two university degrees in comparison to Edward's lack of formal schooling past sixteen, Edward at the age of twenty-three had published 37 scientific papers in comparison to Marsh's two published works.[20] The two men appeared to take a liking to each other; Marsh led Edward on a tour of the city, and they stayed together for several days. After Edward left Berlin the two maintained a correspondence, exchanging manuscripts, fossils, and photographs.[20]

Early career

Upon returning to Philadelphia in 1864 the Cope family made every effort to secure Edward a teaching post as the Professor of Zoology at Haverford College, a small Quaker school that the family had ties to philanthropically.[21] The college awarded him an honorary master’s degree so he could have the position. Cope even began to think about marriage and consulted his father in the matter, telling him of the girl he would like to marry, "an amiable woman, not over sensitive, with considerable energy, and especially one inclined to be serious and not inclined to frivolity and display- the more Christian of course the better- seems to be the most practically the most suitable for me, though intellect and accomplishments have more charm."[21] Cope thought of Annie Pim, a member of the Society of Friends, as less a lover and was more inclined towards, "her amiability and domestic qualities generally, her capability of taking care of a house, etc., as well as her steady seriousness weigh far more with me than any of the traits which form the theme of poets!"[22] In July 1865 at Mary Pim’s hillside house in Chester County Pennsylvania, Edward married Annie Pim. On June 10, 1866 the union would be blessed with Edward’s only child, Julia Biddle Cope.

Cope’s personal life may have been progressing nicely but his professional one was not. Cope found enriching the minds of students at Haverford "a pleasure," but "could not get any work done."[23][24] Pleading with his father for money to pursue his career, he finally sold the farm in 1869 that his father had bought him.[25] He resigned from his position at Haverford and moved his family to Haddonfield, in part to be closer to the fossil beds of western New Jersey.[26]

1870s

Upon the selling of his farm, moving to Haddonfield, and resigning from his position at Haverford, it was decided between Alfred Cope and his son that Edward would become a scientist. He began his professional fossil hunting career in the New Jersey marl pits, where he would find the carnivorous Laelaps, his first large nearly dinosaur skeleton, as well as many smaller dinosaurs, mammoths and other vertebrates of the Cretaceous era.[27] His first synopsis at the Philadelphia Academy was on the extinct amphibia of the world and would begin his trips to the west in 1871.[28] His first trip to Western Kansas amazed Cope. Here was an area in which complete skeletons could be found in the soft sand that was once the sea shore. In subsequent years Cope would journey to Wyoming and Colorado under the direction of the Hayden Survey, in which he discovered 96 new species.

In 1874 Cope was employed with the Wheeler Survey to New Mexico, whose Puerco formations, he wrote to his father, provided “the most important find in geology I have ever made.”[29] The New Mexico bluffs contained millions of years of formation and subsequent deformation. It was an area which had not been visited by either Leidy or Marsh. By being employed in government surveys it helped Cope by being able to draw on Fort commissaries and defraying the costs of publishing. His findings would instead be published in the annual reports that the surveys printed, but there was no actual salary involved. Cope did bring Annie and Julia along on the Hayden survey and rented a house for them at Fort Bridger, but he inherently spent more of his own money on these survey trips than he would have liked.[30] However, the severe desert conditions and Cope’s habit of overworking himself till he was bedridden caught up with him and in 1872 he broke down from over exhaustion. [31] The Agathaumas sylvestris, or ‘marvelous saurian of the forest,’[32] was the crown jewel of this period and was discovered by one of Cope’s collectors, F. B. Meek. He tried to be the first to publish on this dinosaur, knowing that it was something entirely new. So Cope telegrammed the message to the American Philosophical Society, but the telegrapher jumbled the name. This mistake gave Marsh precedence on the naming of the dinosaur he named, Triceratops, which became a household name.

In 1875 Alfred Cope died and left Edward with an inheritance of nearly a quarter of a million dollars. His father’s death was a blow to Edward, who had always confided in him. In the same year he also published the massive volume, Vertebrata of the Cretaceous Formations of the West, nicknamed Cope’s Bible. Cope now had the finances to hire multiple teams to search for fossils for him year round and in 1876 he advised the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition on their fossil displays. In 1877 Cope purchased half the rights to the American Naturalist in order to have an avenue in which to publish the many papers he was churning out at a rate so high that Marsh questioned their dating.[33] In 1878 he went back to Europe for the second time and was treated as a celebrity, giving lectures to museums and scientific societies across the continent. He bought a large selection of fossils that had been unearthed in Argentina and were sold to the American Museum of Natural history in 1899 where they became known as the “Cope Pampean” collection. [34]

The 1870’s were the golden years of Cope’s career, where his most prominent discoveries and when his most rapid flow of publications occurred. In the period of one year from 1879-1880 he published 76 papers when he was traveling through New Mexico and Colorado, and from the findings of his collectors in Texas, Kansas Oregon, Colorado, Wyoming and Utah.[35] His greatest anatomical generalization was published in 1879, his principle on the tritubercular origin of the molar teeth of the mammals. Henry Osborn would in 1907 elaborate further on this theory. This prodigious output was spurred in part by competition from his old Berlin acquaintance, Othniel Marsh.

Bone Wars

Cope's relations with Marsh led to a competition for bones between the two, known today as The Bone Wars, which lasted from about 1877 to 1892. The conflict began upon the men's return to the U.S. they wrote letters to each other and when Cope moved to his Haddonfield home, they visited the New Jersey marl pits together. Cope introduced Marsh to the owner of the pits, Albert Vorhees. This was the start of many problems the two would have over their careers. Marsh would go behind Cope’s back and privately arrange for all the fossils that Vorhees’s men found to be sent back to Marsh at New Haven.[36]

In 1870 the two men had a falling out of sorts. Marsh was at Haddonfield examining one of Cope’s fossil finds, the Elasmosaurus, which was a complete skeleton of a large aquatic plesiosaur that had four flippers and a long neck. Marsh commented that the fossil’s head was on the wrong end, evidently stating that Cope had put the skull at the end of the vertebra of the tail. Cope was outraged and the two argued for some time until the two agreed to have Joseph Leidy come examine the bones and see who was right. Leidy came and simply picked up the head of the fossil and put it on the other end. Cope was horrified since he had already published a paper on the fossil that had the error in it at the American Philosophical Society. He immediately tried to buy back all the copies, but some remained floating around (Marsh kept his as did Leidy).[37] The whole ordeal might have passed easily enough had Leidy not exposed the cover up at the next society meeting, not to in any way alienate Cope but only in response to Cope’s brief retracted statement where he never admitted he was wrong. A few weeks later Cope paid a visit to the marl pits and found that men in Marsh’s employment were busy collecting in an area that Cope had thought his own. The two would never talk to each other amicably again.

Cope was described by all as a genius and what Marsh lacked in intelligence, he easily made up for in connections. Marsh’s uncle was George Peabody, a rich banker who founded the Peabody Museum at Yale. He supported Marsh with money, as well as a secure position at the Peabody museum. His uncle’s money allowed Marsh to pay off anyone, while the political connections, as high as Ulysses S. Grant. Marsh urged John Wesley Powell to request fossils Cope had collected during government surveys and attempted to persuade Ferdinand Hayden, to “muzzle” Cope’s publishing.[38] Both men tried their hardest to spy on the other’s whereabouts and attempted to offer their collectors more money in the hopes of recruiting them to their own side. Cope was able to recruit David Baldwin in New Mexico and Frank Williston in Wyoming from Marsh.[39] They were both extremely secretive as to where there fossils were coming from and when Henry Osborn, at the time a student at Princeton, visited Cope to ask where he and some of his classmates should travel to look for fossils in the West, Cope politely denied them access to the knowledge of where the fossil fields were in Kansas. [40]

When Cope arrived back in the United States after his tour of Europe in 1878, he had nearly two years of fossil findings from O.W. Lucas, a man digging for him in the Morrison Formation of Jurassic sandstone outside Canon City, Colorado. Among these dinosaurs would be the Camarasaurus, a dinosaur that today is one of the most recognizable recreations of this time period.[41] The summer of 1879 took Cope to Salt Lake City, San Francisco and north to Oregon, where he was amazed at the rich flora and the blueness of the Pacific Ocean.[42] In 1879 the United States congress consolidated the survey team into one, U.S. Geological Survey with Clarence King as its leader. This was discouraging because King immediately named his old college buddy and intimate friend, O.C. Marsh, as the chief paleontologist. Cope’s intimate and cordial relationship with his own fossil collectors insured that they stayed loyal to him, no matter how much Marsh offered them to come to his service. Charles Sternberg, J.L. Wortman and David Baldwin were especially prolific, securing some of the finest fossils of the time.

Later years

For 25 years the two greatest paleontologist of their time did not speak to each other and attempted at every turn to discredit each other’s discoveries. Marsh continuously complained of Cope’s rapid publishing pace and accused him of altering dates. Cope in turn accused Marsh of antedating his papers in order to get priority over contested discoveries. The ordeal became public to all those outside of the scientific community when, in response to Marsh’s influence in having Powell pull Cope off of the government survey team, Cope went to the editor of the New York Herald and promised a scandalous headline. Cope over the years had kept an elaborate journal of mistakes and misdeeds that both Marsh and Powell had committed. From scientific errors to publishing mistakes, he had it all written down in a journal that he had kept in the bottom drawer of his Pine Street desk. [43] William Hosea Ballou ran the first article on January 12, 1890, in what would become a series of newspaper debates between Marsh, Powell and Cope.[44] Cope attacked Marsh for plagiarism and financial mismanagement and attacked Powell for his geological classification errors and misspending of government allocated funds.[45] Marsh and Powell were each able to publish their own side of the story and in the end little changed. No congressional hearing was created to investigate the misallocation of funds by Powell and neither Cope nor Marsh was held responsible for any of their mistakes. Marsh was however quickly removed from his position as paleontologist for the government surveys, Cope’s relations with the president of the University of Pennsylvania soured, and the entire funding for paleontology in the government surveys was pulled.[46]

Cope took the whole debacle in stride. In writing to Osborn about the articles he laughed at the outcome, telling Osborn, “It will now rest largely with you whether or not I am supposed to be a liar and am actuated by jealousy and disappointment. I think Marsh is impaled on the horns of Monoclonius sphenocerus.”[47] Both men ended their lives as two of the greatest paleontologists of the time period. They both died in relative obscurity and both spent their sizable inheritances in search of the fossils of the west. Cope was seen as the more intelligent but reckless of the two, while Marsh was better connected politically and more methodical with his work. As a final challenge, Cope dictated that his brain was to be taken out and weighed against Marsh’s brain, to see whose was heavier upon their deaths. Marsh however did not rise to the challenge. Cope was well aware of all of his enemies and was carefree enough to name a species after his many enemies. The new species was a combination of two words: Cope and hater. This new species was called Anisonchus cophater. [48]

Cope's search for mineral wealth from 1881-1889 took a disastrous toll on his finances, and in 1887 he had to sell whatever his stocks were still of worth among the various mining operations in which he had invested. His mining operations went from bad to worse and he was no longer able to afford going to the West every summer for a span of ten years. Things only got worse as Cope was turned down again and again for curator and professorial positions across the U.S. Cope was then forced to rent out his second house on Pine Street and in 1886 his family was forced to move to a small house on the property formerly built for the servants of their grand townhouses. The American Naturalist publishers went bankrupt, the problem being that the review never made any money. Normally Cope would have taken money out of his own pocket to pay the difference, but he was no longer capable of doing so. Cope also had to deal with the thought of losing his enormous fossil collection. John Wesley Powell, the new head of the U.S. Geological Survey team, at the urging of Marsh continued to deny the money to publish his works from the Hayden surveys. This time however Powell pushed for Cope to give back all the specimens that he had unearthed during his employment under the auspices of the U.S. government surveys. This was an outrage to Cope, who in all fairness had used over 75,000 dollars of his own money in the 1870’s when he was working with the survey teams. Cope’s response after continued hearings before congress members was to simply take the case to the newspapers. Nothing eventually happened to Cope, or his collection but Powell was forced to ask Marsh, who had intervened in the debacle, to resign from his position as the chief paleontologist for the survey teams. [49]

Through his years of financial hardship he was still somehow able to continue publishing papers and in 1889 received a position at the University of Pennsylvania as the professor of zoology. [50] It was a small yearly stipend but it was enough for the family to move back into one of the townhouses so that Cope could resume some of his works again. Not until the Texas Geological Survey offered Cope a position in their expeditions in the summers of 1892 was he able to get back into the field once again. His finances having improved, he was able to publish a massive work on the Batrachians of North America, which was the most detailed analysis and organization of the continent's frogs and amphibians ever mastered.[51] Then he would publish an equally daunting book with 1,115 pages, The Crocodilians Lizards and Snakes of North America. These two books along with his short essays on amphibians and reptiles would place Cope as one of the pillars of scientists in these fields. The Copeia,the foremost journal for ichthyologists and herpetologists, was named in Cope’s honor in 1915 because of his work in the field. In the 1890’s his publication rate went back up to an average of 43 articles a year until his death in 1897.[52]

Death

After many years of working in hostile and extreme conditions, Cope’s overexertion over the years finally caught up with him. Cope was confined for a time to bed as his gastrointestinal problems became worse in 1897. His self medication of formalin, a substance based of formaldehyde, used to preserve specimens only made the sickness worse and on April 12, 1897 Cope passed away in his Pine Street home. His brain was removed and given to the Wistar Institute at the University of Pennsylvania. His ashes were placed at the institute with his friends Joseph Leidy and Dr. Ryder. His bones were to be extracted and kept in a locked drawer, not to be put up on exhibit, but to be studied by anatomy students at the University. [53] Many believed Cope had died of syphilis that he had contracted in his travels from the many women he fraternized with. However this theory was laid to rest when Jane Davidson, author of the Bone Sharp, was able to gain permission to have the skeleton examined by a medical doctor at the university. Dr. Morrie Kricun a professor of radiology in 1995 came to the conclusion that there was absolutely no evidence of bony syphilis on Cope’s skeleton. [54]

His wife Annie was given all his possessions, showing that although the two had divorced, they stayed quite close. His fossil collections were to be donated to various museums, with the bulk going to the American Museum of Natural History. In 1939 Julia donated all his memoirs and surviving letters to the museum as well. Whatever could be sold off was, enabling Julia to have a more comfortable life. Cope also paid credit to his longtime collectors and employees by setting aside money for them as well.

Julia would not comment on the name of the woman in whom her father had had the love affair with in Washington D.C. prior to his first European travel. It is believed that Julia burned any of the scandalous letters and journals that Cope had kept but many of his friends were able to give their recollections of the scandalous nature of some of Cope’s unpublished routines. Charles Knight, a former friend called, “Cope’s mouth the filthiest, from hearsay that in his heyday [Copes’s] no woman was safe within five miles (8 km) of him.”[55] Julia was the major financer behind Henry Osborn’s Cope: The Master Naturalist, and therefore wanted to keep her father’s name in good standing and refused to comment on any misdeeds her father may have committed.

Theories and beliefs

His views on human evolution would today be considered racist, but for the time were used by many scientists as an excuse for imperialism. He believed that if, “a race was not white then it was inherently more ape-like.”[56] However he was not opposed to blacks because of the color of their skin but to their “degrading vices,” believing that the “inferior Negro should go back to Africa.”[57] He did not blame blacks for their bad vices, but wrote that, “A vulture will always eat carrion when surrounded on all hands by every kind of cleaner food. It is the nature of the bird.”[58] Cope was against women’s rights, believing in the husband’s role as protector. He published papers on the marriage problem, noting that women were muscularly inferior to men because they did not have the jobs that required them to have muscles. Strangely enough he believed in education for women and people of all races, in order to make oneself a better individual and to better contribute to society.

Cope was raised as a Quaker, and was taught that the bible was literal truth. Though he never confronted his family about their religious views, Osborn writes that Cope was at least aware of the conflict between his scientific career and his religion. Osborn writes: "If Edward harbored intellectual doubts about the literalness of the bible ... he did not express them in his letters to his family but there can be little question ... that he shared the intellectual unrest of the period."[59] Biographer Jane Davidson writes that Osborn seems to have overstated Cope's internal religious conflicts. Davidson ascribes Cope's deference to his father's beliefs as an act of respect or a measure to retain his father's financial support.[60]

Cope was a staunch Neo-Lamarckian, believing individuals can pass on traits acquired in its lifetime to offspring.[61] He read Charles Darwin’s Voyage of a Naturalist as a young man, with the book having little effect on him. The only comment about Darwin's book recorded by Cope was that Darwin had discussed “too much geology” from the account of his voyage.[62]

In 1887, Cope published his own Origin of the Fittest: Essays in Evolution. [63] Cope was one on the strongest American supporters of the Neo-Lamarckism school of evolution, he believed in evolution, but not in Darwin’s theory of natural selection as a means to that end. Cope was a strong believer in the law of use and disuse, that an individual will slowly, over time, favor an anatomical part of its body so much that it will become stronger and larger as time progresses down the generations. The giraffe, for example, stretched its neck to reach taller trees and passed this acquired characteristics to its offspring in the new developmental phase that is added on to the fetus in the womb. This new stage of sharing of genetics would be added on after all gestation is completed and the offspring is ready to be conceived. [64]

Legacy

In less than 40 years as a scientist Cope published over 1,200 scientific papers, a record that still stands to this day.[65] These include three major volumes: On the Origin of Genera (1867), The Vertebrata of the Tertiary Formations of the West (1884: "Cope's bible") and The Origin of the Fittest: Essays in Evolution (1887). His greatest anatomical generalization on the origin of mammalian molars and ‘Cope’s Law’ on the gradual enlargement of a population lineage tends to increase body size over geological time,[66] are testaments to the brilliance and attention to detail that Cope commanded. He was an outspoken proponent for Neo-Lamarckism and although he loved his own theories, “he was never blind to the possibility of them being disproved.”[67] During his career he discovered and described over 1,000 species of fossil vertebrates and published 600 separate titles.[68] The most prolific journal on amphibians and reptiles, Copeia, is named after him, as well as many other species that he discovered or was named in his honor, such as the Gambelia copeii. He was an active member of many different scientific societies, most notably the American Academy of Sciences and the American Philosophical society. His childhood home at “Fairfield” and his Pine Street homes are recognized as national landmarks.[69] A plaque honoring Cope stands outside the Academy of Natural Sciences and countless other memorials across the U.S. have been erected in Cope’s name.

The salamander, Dicamptodon copei Nussbaum, 1970; the toad, Bufo americanus copei H. C. Yarrow and Henshaw, 1878; the lizard Gambelia wislizenii copeii (H. C. Yarrow, 1882) and the snake Cemophora coccinea copei Jan, 1863 were named for Cope by various other naturalists. [2]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Davidson, 7.

- ↑ Lanham, 60-63.

- ↑ Davidson, 8.

- ↑ Osborn, 40.

- ↑ Davidson, 9.

- ↑ Davidson, 12.

- ↑ Davidson, 11.

- ↑ Davidson, 15.

- ↑ Osborn, p. 100.

- ↑ Davidson, 17.

- ↑ Davidson, 20.

- ↑ Osborn, 80.

- ↑ Osborn, 101.

- ↑ Davidson, 21.

- ↑ Osborn, 107.

- ↑ Osborn, 106.

- ↑ Osborn, 138.

- ↑ Cope correspondence, letter 54, 12 March 1863.

- ↑ Davidson, 29.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Jaffe, 11.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Jaffe, 48.

- ↑ Cope correspondence, letter 70, 11 February 1864.

- ↑ Osborn, 143.

- ↑ Davidson, 31.

- ↑ Davidson, 33.

- ↑ Osborn, 144.

- ↑ Osborn, p. 156

- ↑ Osborn, p. 157.

- ↑ Osborn, p. 200.

- ↑ Jaffe, 63

- ↑ Jaffe, 583

- ↑ Jaffe, 75

- ↑ Davidson, 41.

- ↑ Davidson, 42.

- ↑ Davidson, 43

- ↑ William B. Gallagher, When Dinosaurs Roamed New Jersey (New Brunswick, N.J., Rutgers University Press, 1997), 35.

- ↑ Jaffe, 15

- ↑ Jaffe, 106

- ↑ Jaffe, 257

- ↑ Osborn, p. 579.

- ↑ Davidson, 42.

- ↑ Osborn, p. 269.

- ↑ Osborn, p. 585.

- ↑ Osborn, p. 403.

- ↑ Osborn Osborn, p. 404.

- ↑ Jaffe, 329.

- ↑ Osborn, 408.

- ↑ Osborn, 583.

- ↑ Jaffe, 334

- ↑ Jaffe, 317.

- ↑ Jaffe, 350.

- ↑ Jaffe, 348.

- ↑ Davidson, Bone Sharp, p.160.

- ↑ Davidson, 161.

- ↑ Davidson, 109.

- ↑ Davidson, 169.

- ↑ Davidson, 176.

- ↑ Davidson, 182.

- ↑ Davidson, 23.

- ↑ Davidson, 24.

- ↑ Polly.

- ↑ Davidson, 16.

- ↑ Alroy.

- ↑ Cope, Edward Drinker. The Origin of the Fittest. Reprint 1974 Arno Press Inc. New York, NY, D. Appleton and Company, 1887, p.126

- ↑ Jaffe, Mark. “The Profile of Edward Drinker Cope.” Niagara Museum .com 2004. 10 April 2008. [1]

- ↑ Hone, Benton.

- ↑ Osborn, p. 583

- ↑ “Cope.” Dino Data.com. 2008. 10 April 2008. <http://www.dinodata.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1149&Itemid=108>

- ↑ Levins, Hoag. “Local Pioneer Dinosaur Hunter Honored.” Historic camden county.com 7 Nov. 2008. 10 April 2008. < http://historiccamdencounty.com/ccnews44.shtml>

References

- Alroy, John (1999-10-02). "Edward Drinker Cope (1840-1897)". National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis. University of California, Santa Barbara. Retrieved on 2008-11-17.

- Hone, D.W.; Benton, M.J. (January 2005). "The evolution of large size: how does Cope's Rule work". Trends in Ecology and Evolution 20 (1): pp. 4–6. doi:. PMID 16701331.

- Davidson, Jane (1997). The Bone Sharp: The Life of Edward Drinker Cope. Academy of Natural Sciences. ISBN 0-910-00653-9.

- Jaffe, Mark (2000). The Gilded Dinosaur: The Fossil War Between E. D. Cope and O. C. Marsh and the Rise of American Science. New York: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 0-517-70760-8.

- Lanham, Url (1973). The Bone Hunters. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-03152-1.

- Osborn, Henry Fairfield (1978). Cope: Master Naturalist : Life and Letters of Edward Drinker Cope, With a Bibliography of His Writings. Manchester, New Hampshire: Ayer Company Publishing. ISBN 0-405-10735-8.

- Polly, David (1997-06-06). "Edward Drinker Cope (1840-1897)". University of California Museum of Paleontology. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved on 2008-09-19.

External links

- Bibliography of dinosaur-related references at DinoData

- Dinosaurs named by Cope, at DinoData

- Biographies of Persons honored in the Herpetological Nomenclature

- Edward Drinker Cope Papers, 1848-1940, Haverford College Special Collections