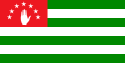

Abkhazia

| Republic of Abkhazia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: "Aiaaira" ("Victory") |

||||||

Map of Abkhazia

|

||||||

Location of Abkhazia

|

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) |

Sukhumi |

|||||

| Official languages | Abkhaz, Russian1 | |||||

| Non-official languages | Mingrelian,2 Armenian, Georgian | |||||

| Demonym | Abkhazian, Abkhaz | |||||

| Government | Unitary republic | |||||

| - | President | Sergei Bagapsh (United Abkhazia) | ||||

| - | Vice President | Raul Khadjimba (Forum of Abkhaz People’s Unity) | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Alexander Ankvab (Aytayra) | ||||

| Partially recognised independence from Georgia and the Soviet Union[1][2][3] | ||||||

| - | Georgian annulment of all Soviet-era laws and treaties | 20 June 1990 | ||||

| - | Declaration of sovereignty3 | 25 August 1990 | ||||

| - | Georgian declaration of independence | 9 April 1991 | ||||

| - | Dissolution of Soviet Union | 26 December 1991 | ||||

| - | Reinstatement of 1925 Constitution | 23 July 1992 | ||||

| - | New Constitution | 26 November 1994 | ||||

| - | Referendum | 3 October 1999 | ||||

| - | Act of state independence4 | 12 October 1999 | ||||

| - | First international recognition5 | 26 August 2008 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 8,432 km2 3,256 sq mi |

||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | estimate | Between 157,000 and 190,0006 180,0007 |

||||

| - | 2003 census | 216,000 (disputed) | ||||

| - | Density | 29/km2 75.1/sq mi |

||||

| Currency | Russian ruble8 (RUB) |

|||||

| Time zone | MSK (UTC+3) | |||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| 1 | Russian has co-official status and widespread use by government and other institutions. | |||||

| 2 | Mingrelian is spoken largely in the Gali district. | |||||

| 3 | Anulled by the Georgian Soviet immediately after. | |||||

| 4 | Establishing retro-actively de jure independence since the 1992-1993 war. | |||||

| 5 | By Russia. Only since followed by Nicaragua. | |||||

| 6 | International Crisis Group 2006 estimate. | |||||

| 7 | Encyclopædia Britannica 2007 estimate. | |||||

Abkhazia (Abkhaz: Аҧсны Apsny, Georgian: აფხაზეთი Apkhazeti or Abkhazeti, Russian: Абха́зия Abkhazia) is a disputed region and a de facto independent[4][5][6][7], partially recognized country. It lies on the eastern coast of the Black Sea, which forms its southern border, bordering on Russia to the north and Georgia to the east.[8][9] The Republic of Abkhazia, with Sukhumi as its capital, is recognized by Russia, Nicaragua, and the de facto independent republics of South Ossetia and Transnistria,[10] while most of the European Union, OSCE, and NATO states recognize Abkhazia as an integral part of the territory of Georgia.[11][12][13][14][15]

Georgia considers Abkhazia part of its territory and has designated the province, in its official subdivisions, as an autonomous republic (Georgian: აფხაზეთის ავტონომიური რესპუბლიკა, Abkhaz: Аҧснытәи Автономтәи Республика, Apsnitei Avtonomtei Respublika), bordering the region of Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti to the east. On 28 August 2008, the Parliament of Georgia passed a resolution declaring Abkhazia a "Russian-occupied territory."[16][17]

The secessionist movement of the Abkhaz minority led to the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict. The War in Abkhazia resulted in a Georgian military defeat and the mass exodus and ethnic cleansing of the Georgian population from Abkhazia. In spite of the 1994 ceasefire accord and the ongoing UN-monitored and Russian-dominated CIS peacekeeping operation, the sovereignty dispute has not yet been resolved. This dispute remains a source of a conflict between Georgia and Russia.

In July 2006, Georgian forces launched a successful police operation against the rebelled administrator of the Georgian populated Kodori Gorge, Emzar Kvitsiani. Kvitsiani had been appointed there by the previous president of Georgia Edvard Shevardnadze and was refusing to recognize the authority of president Mikheil Saakashvili, who succeeded Shevardnadze after the Rose Revolution. Although Kvitsiani escaped the capture by Georgian police, the Kodori Gorge was brought back under the control of the central government in Tbilisi. During 2008 South Ossetia War in August 2008, Russian and Abkhazian forces attacked the Georgian police units located in the region and occupied Kodori Gorge, which had never been under the Abkhazian-Russian control before. The majority of the population was forced to flee the gorge and to move Western Georgia. Promptly, the Russian Federation has rescinded its recognition of Georgian sovereignty over Abkhazia,[18] diplomatically recognizing the independence of Abkhazia on 26 August 2008.

Contents |

History

Early history

In the 9th–6th centuries BC, the territory of modern Abkhazia became a part of the ancient Georgian kingdom of Colchis (Kolkha), which was absorbed in 63 BC into the Kingdom of Egrisi. Greek traders established ports along the Black Sea shoreline. One of those ports, Dioscurias, eventually developed into modern Sukhumi, Abkhazia's traditional capital.

The Roman Empire conquered Egrisi in the 1st century AD and ruled it until the 4th century, following which it regained a measure of independence, but remained within the Byzantine Empire's sphere of influence. Although the exact time when the population of Abkhazia was converted to Christianity is not determined, it is known that the Metropolitan of Pitius participated in the First Oecumenical Council in 325 in Nicea. Abkhazia was made an autonomous principality of the Byzantine Empire in the 7th century — a status it retained until the 9th century, when it was united with the province of Imereti and became known as the Abkhazian Kingdom. In 9th–10th centuries the Georgian kings tried to unify all the Georgian provinces and in 1001 King Bagrat III Bagrationi became the first king of the unified Georgian Kingdom.

In the 16th century, after the break-up of the united Georgian Kingdom, an autonomous Principality of Abkhazia (abxazetis samtavro in Georgian) emerged, ruled by the Shervashidze dynasty (aka Sharvashidze, or Chachba). Since the 1570s, when the Ottoman navy occupied the fort of Tskhumi, Abkhazia came under the influence of Ottoman Empire and Islam. Under the Ottoman rule, the majority of Abkhazians were converted to Islam, and the Abkhazian ruling dynasty Shervashidze lost their ties with the Christian Georgian nobility.

Abkhazia within the Russian Empire and Soviet Union

In the beginning of 19th century when Russians and Ottomans struggled for control of the region, the rules of Abkhazia shifted back and forth across the religious divide. The first attempt to enter into relation with Russia was made by Keilash Beyin 1803, shortly after the incorporation of eastern Georgia into the expanding Tsarist empire (1801). However, the pro-Ottoman orientation prevailed for a short time after his assassination by his son Aslan-Bey in 2 May 1808. On 2 July 1810, the Russian Marines stormed Suhum-Kale and had Aslan-Bey replaced with his rival brother, Sefer-Bey (1810-1821), who had become converted to Christianity and assumed the name of George. Abkhazia joined the Russian empire as an autonomous principality. However, George’s rule, as well of his successors, was limited to the neighbourhood of Suhum-Kale and the Bzyb area. The next Russo-Turkish war strongly enhanced the Russian positions, leading to a further split in the Abkhaz elite, mainly along religious divisions. During the Crimean War (1853 - 1856), Russian forces had to evacuate Abkhazia and Prince Michael (1822-1864) seemingly switched to the Ottomans. Later on, the Russian presence strengthened and the highlanders of Western Caucasia were finally subjugated by Russia in 1864. The autonomy of Abkhazia, which had functioned as a pro-Russian "buffer zone" in this troublesome region, was no more needed to the Tsarist government and the rule of the Shervashidze came to an end; in November 1864, Prince Michael was forced to renounce his rights and resettle in Voronezh. Abkhazia was incorporated in the Russian Empire as a special military province of Suhum-Kale which was transformed, in 1883, into an okrug as part of the Kutais Guberniya. Large numbers of Muslim Abkhazians — said to have constituted as much as 60% of the Abkhazian population, although contemporary census reports were not very trustworthy — emigrated to the Ottoman Empire between 1864 and 1878 together with other Muslim population of Caucasus in the process known as Muhajirism.

Large areas of the region were left uninhabited and many Armenians, Georgians, Russians and others subsequently migrated to Abkhazia, resettling much of the vacated territory.[19] According to Georgian historians Georgian tribes (Mingrelians and Svans) had populated Abkhazia since the time of the Colchis kingdom.[20] Some Georgian scholars even claim that the Abkhaz are the descendants of North Caucasian tribes, who migrated to Abkhazia from the north of the Caucasus Mountains and merged there with the existing Georgian population. However, this theory has little support among most Georgian academics.[21][22]

The Russian Revolution of 1917 led to the creation of an independent Georgia (which included Abkhazia) in 1918. Georgia's Menshevik government had problems with the area through most of its existence despite a limited autonomy being granted to the region. In 1921, the Bolshevik Red Army invaded Georgia and ended its short-lived independence. Abkhazia was made a Socialist Soviet Republic (SSR Abkhazia) with the ambiguous status of a treaty republic associated with the Georgian SSR.[23][24] In 1931, Stalin made it an autonomous republic (Abkhaz Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic or in short Abkhaz ASSR) within the Georgian SSR. Despite its nominal autonomy, it was subjected to strong direct rule from central Soviet authorities. Georgian became the official language. Purportedly, Lavrentiy Beria encouraged Georgian migration to Abkhazia, and many took up the offer and resettled there. Russians also moved into Abkhazia in great numbers. Later, in the 1950s and 1960s, Vazgen I and the Armenian church encouraged and funded the migration of Armenians to Abkhazia. Currently, Armenians are the second largest minority group in Abkhazia (closely matching the Georgians), although their numbers decreased dramatically from 77,000 in the 1989 census to 45,000 in the 2003 census (see the Demographics).

The oppression of the Abkhaz was ended after Stalin's death and Beria's execution, and Abkhaz were given a greater role in the governance of the republic. As in most of the smaller autonomous republics, the Soviet government encouraged the development of culture and particularly of literature. Ethnic quotas were established for certain bureaucratic posts, giving the Abkhaz a degree of political power that was disproportionate to their minority status in the republic. This was interpreted by some as a "divide and rule" policy whereby local elites were given a share in power in exchange for support for the Soviet regime. In Abkhazia as elsewhere, it led to other ethnic groups - in this case, the Georgians - resenting what they saw as unfair discrimination, thereby stoking ethnic discord in the republic.

Abkhazia in Post-Soviet Georgia

As the Soviet Union began to disintegrate at the end of the 1980s, ethnic tensions grew between the Abkhaz and Georgians over Georgia's moves towards independence. Many Abkhaz opposed this, fearing that an independent Georgia would lead to the elimination of their autonomy, and argued instead for the establishment of Abkhazia as a separate Soviet republic in its own right. The dispute turned violent on 16 July 1989 in Sukhumi. Sixteen Georgians are said to have been killed and another 137 injured when they tried to enroll in a Georgian University instead of an Abkhaz one. After several days of violence, Soviet troops restored order in the city and blamed rival nationalist paramilitaries for provoking confrontations.

The Republic of Georgia boycotted the 17 March 1991 all-Union referendum on the renewal of the Soviet Union called by Mikhail Gorbachev - but 52.3% of the Abkhazia's population (virtually all the ethnic non-Georgians) took part in the referendum and voted by an overwhelming majority (98.6%) to preserve the Union.[25][26] Most ethnic non-Georgians later boycotted a 31 March referendum on Georgia’s independence, which was supported by a huge majority of Georgia's population. Within weeks, Georgia declared independence on 9 April 1991, under former Soviet dissident Zviad Gamsakhurdia. Under Gamsakhurdia, the situation was relatively calm in Abkhazia and a power-sharing agreement was soon reached between the Abkhaz and Georgian factions, granting to the Abkhaz a certain overrepresentation in the local legislature.

Gamsakhurdia's rule was soon challenged by the armed opposition groups which, under the command of Tengiz Kitovani, forced him to flee the country in a military coup in January 1992. Former Soviet foreign minister and architect of the disintegration of the USSR Eduard Shevardnadze replaced Gamsakhurdia as president, inheriting a government dominated by hardline Georgian nationalists. He was not an ethnic nationalist but did little to avoid being seen as supporting his administration's dominant figures and the leaders of the coup that swept him to power.

On 21 February 1992, Georgia's ruling Military Council announced that it was abolishing the Soviet-era constitution and restoring the 1921 Constitution of the Democratic Republic of Georgia. Many Abkhaz interpreted this as an abolition of their autonomous status, although the 1921 constitution contained a provision for the region's autonomy.[27] On 23 July 1992, the Abkhaz faction in the republic's Supreme Council declared effective independence from Georgia, although the session was boycotted by ethnic Georgian deputies and the gesture went unrecognised by any other country. The Abkhaz leadership launched a campaign of ousting Georgian officials from their offices, a process which was accompanied by violence. In the meantime, the Abkhaz leader Vladislav Ardzinba intensified his ties with the hardliner Russian politicians and military elite and declared he was ready for a war with Georgia.[28]

The Abkhazian War

In August 1992, the Georgian government accused Gamsakhurdia's supporters of kidnapping Georgia's interior minister and holding him captive in Abkhazia. The Georgian government dispatched 3,000 troops to the region, ostensibly to restore order. The Abkhaz were relatively unarmed at this time and the Georgian troops were able to march into Sukhumi with relatively little resistance[29] and subsequently engaged in ethnically based pillage and looting.[30] The Abkhaz units were forced to retreat to Gudauta and Tkvarcheli.

The Abkhaz military defeat was met with a hostile response by the self-styled Confederation of Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus, an umbrella group uniting a number of pro-Russian movements in the North Caucasus, including Circassians, Abazas, Chechens, Cossacks, Ossetians and hundreds of volunteer paramilitaries from Russia, including the then little-known Shamil Basayev, later a leader of the anti-Moscow Chechen secession, sided with the Abkhaz separatists to fight the Georgian government. Regular Russian forces also reportedly sided with the secessionists. In September, the Abkhaz and Russian paramilitaries mounted a major offensive against Gagra after breaking a cease-fire, which drove the Georgian forces out of large swathes of the republic. Shevardnadze's government accused Russia of giving covert military support to the rebels with the aim of "detaching from Georgia its native territory and the Georgia-Russian frontier land". The year 1992 ended with the rebels in control of much of Abkhazia northwest of Sukhumi. The conflict stalemated until July 1993, when Abkhaz separatist militias launched an abortive attack on Georgian-held Sukhumi. They surrounded and heavily shelled the capital, where Shevardnadze was trapped. The warring sides agreed to a Russian brokered truce in Sochi at the end of July, but it collapsed in mid-September 1993 after a renewed Abkhaz attack. After ten days of heavy fighting, Sukhumi was taken over by the Abkhazian forces on 27 September 1993. Shevardnadze narrowly escaped death, after vowing to stay in the city no matter what. He was forced to flee when separatist snipers fired on the hotel where he was staying. Abkhaz, North Caucasian militants and their allies committed numerous atrocities[31] against the city's remaining ethnic Georgians, in what has been dubbed the Sukhumi Massacre. The mass killings and destruction continued for two weeks, leaving thousands dead and missing.

The Abkhaz forces quickly overran the rest of Abkhazia as the Georgian government faced a second threat: an uprising by the supporters of the deposed Zviad Gamsakhurdia in the region of Mingrelia (Samegrelo). In the chaotic aftermath of defeat almost all ethnic Georgians fled the region, escaping an ethnic cleansing initiated by the victors. Many thousands died—it is estimated that between 10,000-30,000 ethnic Georgians and 3,000 ethnic Abkhaz may have perished—and some 250,000 people (mostly Georgians) were forced into exile.[31][32]

During the war, gross human rights violations were reported on the both sides (see Human Rights Watch report[31]). In the first phase of the war, Georgian troops have been accused of looting[29] while Georgia blames the Abkhaz forces and their allies for an intentional ethnic cleansing of Georgians in Abkhazia, which has also been recognized by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Summits in Budapest (1994),[33] Lisbon (1996)[34] and Istanbul (1999).[35] UN Security Council passed series of resolutions in which is appeals for a cease-fire and condemned the Abkhazian policy of ethnic-cleansing.[36]

Of about 200,000-240,000 Georgian refugees, some 60,000 Georgian refugees spontaneously returned to Abkhazia's Gali district between 1994 and 1998, but tens of thousands were displaced again when fighting resumed in the Gali district in 1998. Nevertheless from 40,000 to 60,000 refugees have returned to the Gali district since 1998, including persons commuting daily across the ceasefire line and those migrating seasonally in accordance with agricultural cycles.[37] The human rights situation remained precarious for a while in the Georgian-populated areas of the Gali district. The United Nations and other international organizations have been fruitlessly urging the Abkhaz de facto authorities "to refrain from adopting measures incompatible with the right to return and with international human rights standards, such as discriminatory legislation... [and] to cooperate in the establishment of a permanent international human rights office in Gali and to admit United Nations civilian police without further delay."[38] Key officials of the Gali district are virtually all ethnic Abkhaz, though their support staff are ethnic Georgian.[39]

Post-war Abkhazia

On 3 October 2004 presidential elections were held in Abkhazia. In the elections, Russia evidently supported Raul Khadjimba, the prime minister backed by the ailing outgoing separatist President Vladislav Ardzinba. Posters of Russia's President Vladimir Putin together with Khadjimba, who like Putin had worked as a KGB official, were everywhere in Sukhumi. Deputies of Russia's parliament and Russian singers, led by Joseph Kobzon, a deputy and a popular singer, came to Abkhazia campaigning for Khadjimba.

However Raul Khadjimba lost the elections to Sergei Bagapsh. The tense situation in the republic led to the cancellation of the election results by the Supreme Court. After that a deal was struck between former rivals to run jointly — Bagapsh as a presidential candidate and Khadjimba as a vice presidential candidate. They received more than 90% of the votes in the new election.

Sporadic acts of violence continued throughout the post war years. Despite the peacekeeping status of the Russian peacekeepers in Abkhazia, Georgian officials routinely cited Russian peacekeepers as inciting violence by supplying Abkhaz rebels with arms and financial support. Russian support of Abkhazia became pronounced when the Russian ruble became the de facto currency and Russia began issuing passports to the population of Abkhazia.[40] There have also been several alleged airspace violations including incidents where Russia helicopters attacked Georgian-controlled towns in the Kodori Gorge and in April 2008, a Russian MiG - prohibited from Georgian airspace, including Abkhazia - shot down a Georgian UAV.[41][42]

On 9 August 2008, Abkhazian forces fired on Georgian forces in Kodori Gorge. This coincided with the 2008 South Ossetia war where Russia decided to back up Ossetian separatists who had been attacked by Georgia. The conflict escalated into a full-blown war between the Russian Federation and the Republic Of Georgia. On 10 August 2008 an estimated 9,000 Russian troops entered Abkhazia ostensibly to reinforce the Russian peacekeepers in the republic. About 1,000 Abkhazian troops moved to expel the residual Georgian forces within Abkhazia in the Upper Kodori Gorge.[43] By 12 August the Georgian forces and civilians had evacuated the last part of Abkhazia under Georgian government control. Russia recognized the independence of Abkhazia on 26 August 2008.[44] Moreover, on 17 November 2008, the Abkhaz parliament ratified a bill which authorizes the construction of a Russian military base in Abkhazia in 2009.

International status

The Russian Federation and Nicaragua officially recognized Abkhazia after the 2008 South Ossetia War. The unrecognized republic of Transnistria and the partially recognized republic of South Ossetia have recognized Abkhazia since 2006. Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Transnistria, and the unrecognized republic of Nagorno-Karabakh all belong to the Commonwealth of Unrecognized States, a group that attempts to further the cause of unrecognized states that came from the former Soviet Union. Abkhazia is also a member of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO). All other sovereign states recognise Abkhazia as an integral part of Georgia and support its territorial integrity according to the principles of the international law although Belarus and Venezuela have expressed sympathy toward the recognition of Abkhazia.[45][46][47] The United Nations are urging both sides to settle the dispute through diplomatic dialogue and ratifying the final status of Abkhazia in the Georgian constitution.[31][48] However, the Abkhaz de facto government considers Abkhazia a sovereign country, even though it is only recognised by Russia and Nicaragua. In early 2000, then-UN Special Representative of the Secretary General Dieter Boden and the Group of Friends of Georgia, consisting of the representatives of Russia, the United States, Britain, France, and Germany, drafted and informally presented a document to the parties outlining a possible distribution of competencies between the Abkhaz and Georgian authorities, based on a core respect for Georgian territorial integrity. The Abkhaz side, however, has never accepted the paper as a basis for negotiations.[49] Eventually, Russia also withdrew its approval of the document.[50] In 2005 and 2008, the Georgian government offered Abkhazia a high degree of autonomy and possible federal structure within the borders and jurisdiction of Georgia.

On 18 October 2006, the People's Assembly of Abkhazia passed a resolution, calling upon Russia, international organizations, and the rest of the international community to recognize Abkhaz independence on the basis that Abkhazia possesses all the properties of an independent state.[51] The United Nations has reaffirmed "the commitment of all Member States to the sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of Georgia within its internationally recognized borders" and outlined the basic principles of conflict resolution which call for immediate return of all displaced persons and for non-resumption of hostilities.[52]

Georgia accuses the Abkhaz secessionists of having conducted a deliberate campaign of ethnic cleansing of 200,000-240,000 Georgians, a claim supported by the OSCE (Budapest, Lisbon and Istanbul declaration), United Nations (General Assembly Resolution 10708) and many Western governments.[53][54] The UN Security Council has avoided use of the term "ethnic cleansing" but has affirmed "the unacceptability of the demographic changes resulting from the conflict".[55] On 15 May 2008 United Nations General Assembly adopted a non-binding resolution recognising the right of all refugees (including victims of reported “ethnic cleansing”) to return to Abkhazia and their property rights. It "regretted" the attempts to alter pre-war demographic composition and called for the "rapid development of a timetable to ensure the prompt voluntary return of all refugees and internally displaced persons to their homes."[56]

On 28 March 2008, the President of Georgia Mikheil Saakashvili unveiled his government's new proposals to Abkhazia: the broadest possible autonomy within the framework of a Georgian state, a joint free economic zone, representation in the central authorities including the post of vice-president with the right to veto Abkhaz-related decisions.[57] The Abkhaz leader Sergei Bagapsh rejected these new initiatives as "propaganda", leading to Georgia's complaints that this skepticism was "triggered by Russia, rather than by real mood of the Abkhaz people."[58]

On 3 July 2008, the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly passed a resolution at its annual session in Astana, expressing concern over Russia’s recent moves in breakaway Abkhazia. The resolution calls on the Russian authorities to refrain from maintaining ties with the breakaway regions “in any manner that would constitute a challenge to the sovereignty of Georgia” and also urges Russia “to abide by OSCE standards and generally accepted international norms with respect to the threat or use of force to resolve conflicts in relations with other participating States.”[59]

Russian Involvement

During the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict, Russian authorities and military supplied logistical and military aid to the separatist side.[31] Today, Russia still maintains a strong political and military influence over separatist rule in Abkhazia. Russia has also issued passports for the citizens of Abkhazia since 2000 (as the Abkhazian passports cannot be used for international travel) and subsequently paid retirement pensions and other monetary benefits. More than 80% of the Abkhazian population received Russian passports by 2006; however, Abkhazians do not pay Russian taxes, or serve in the Russian Army.[39][60] About 53,000 Abkhazian passports have been issued as of May 2007.[61]

Moscow, at certain times, had hinted that it might recognize Abkhazia and South Ossetia when the Western countries recognized the independence of Kosovo suggesting it created a precedent. Following Kosovo's declaration of independence the Russian parliament released a joint statement reading: "Now that the situation in Kosovo has become an international precedent, Russia should take into account the Kosovo scenario...when considering ongoing territorial conflicts."[62] Initially Russia continued to delay recognition of both of these republics. However, on 16 April 2008, the outgoing Russian president Vladimir Putin instructed his government to establish official ties with South Ossetia and Abkhazia, leading to Georgia's condemnation of what it described an attempt at "de facto annexation"[63] and criticism from the European Union, NATO, and several Western governments.[64]

Later in April 2008, Russia accused Georgia of trying to exploit the NATO support in order to control Abkhazia by force, and announced it would increase its military in the region, pledging to retaliate militarily to Georgia’s efforts. The Georgian Prime Minister Lado Gurgenidze had said Georgia will treat any additional troops in Abkhazia as "aggressors".[65]

In response to the conflict in Georgia, the Federal Assembly of Russia called an extraordinary session for 25 August 2008 to discuss recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia.[66] Following a unanimous resolution that was passed by both houses of the parliament, calling on the Russian president to recognize independence of the breakaway republics,[67]

Russian president, Dmitry Medvedev, officially recognized both on 26 August 2008.[68][69] Russian recognition [70] was condemned by NATO nations , OSCE chairman, European Council nations[71][72][73][74][75] due to "violation of territorial integrity and international law".[76][77] However it was soon pointed out that the condemning nations had earlier ignored Russia's warnings in their haste to recognise breakaway Kosovo's independence claims from Serbia[78] and despite being a signatory to United Nations resolution 1244 (calling for respecting "territorial integrity" of Serbia[79]). UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon has stated that sovereign states have to decide upon the recognition of independence.[80]

International involvement

The UN has played various roles during the conflict and peace process: a military role through its observer mission (UNOMIG); dual diplomatic roles through the Security Council and the appointment of a Special Envoy, succeeded by a Special Representative to the Secretary-General; a humanitarian role (UNHCR and UNOCHA); a development role (UNDP); a human rights role (UNCHR); and a low-key capacity and confidence-building role (UNV). The UN’s position has been that there will be no forcible change in international borders. Any settlement must be freely negotiated and based on autonomy for Abkhazia legitimized by referendum under international observation once the multi-ethnic population has returned.[81] According to Western interpretations the intervention did not contravene international law since Georgia, as a sovereign state, had the right to secure order on its territory and protect its territorial integrity.

OSCE has increasingly engaged in dialogue with officials and civil society representatives in Abkhazia, especially from NGOs and the media, regarding human dimension standards and is considering a presence in Gali. OSCE expressed concern and condemnation over ethnic cleansing of Georgians in Abkhazia during the 1994 Budapest Summit Decision[82] and later at the Lisbon Summit Declaration in 1996.[83]

The USA rejects the unilateral secession of Abkhazia and urges its integration into Georgia as an autonomous unit. In 1998 the USA announced its readiness to allocate up to $15 million for rehabilitation of infrastructure in the Gali region if substantial progress is made in the peace process. USAID has already funded some humanitarian initiatives for Abkhazia. The USA has in recent years significantly increased its military support to the Georgian armed forces but has stated that it would not condone any moves towards peace enforcement in Abkhazia.

On 22 August 2006, Senator Richard Lugar, then visiting Georgia's capital Tbilisi, joined the Georgian politicians in criticism of the Russian peacekeeping mission, stating that "the U.S. administration supports the Georgian government’s insistence on the withdrawal of Russian peacekeepers from the conflict zones in Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali district."[84]

On 5 October 2006, Javier Solana, the High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy of the European Union, ruled out the possibility of replacing the Russian peacekeepers with the EU force."[85] On 10 October 2006, EU South Caucasus envoy Peter Semneby noted that "Russia's actions in the Georgia spy row have damaged its credibility as a neutral peacekeeper in the EU's Black Sea neighbourhood."[86]

On 13 October 2006, the UN Security Council unanimously adopted a resolution, based on a Group of Friends of the Secretary-General draft, extending the UNOMIG mission until 15 April 2007. Acknowledging that the "new and tense situation" resulted, at least in part, from the Georgian special forces operation in the upper Kodori Valley, the resolution urged the country to ensure that no troops unauthorized by the Moscow ceasefire agreement were present in that area. It urged the leadership of the Abkhaz side to address seriously the need for a dignified, secure return of refugees and internally displaced persons and to reassure the local population in the Gali district that their residency rights and identity will be respected. The Georgian side is "once again urged to address seriously legitimate Abkhaz security concerns, to avoid steps which could be seen as threatening and to refrain from militant rhetoric and provocative actions, especially in upper Kodori Valley". Calling on both parties to follow up on dialogue initiatives, it further urged them to comply fully with all previous agreements regarding non-violence and confidence-building, in particular those concerning the separation of forces. Regarding the disputed role of the peacekeepers from the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Council stressed the importance of close, effective cooperation between UNOMIG and that force and looked to all sides to continue to extend the necessary cooperation to them. At the same time, the document reaffirmed the "commitment of all Member States to the sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of Georgia within its internationally recognized borders."[87]

The HALO Trust, an international non-profit organisation that specialises in the removal of the debris of war, has been active in Abkhazia since 1999 and has completed the removal of land-mines in Sukhumi and Gali districts. It plans to finish its operations in 2007/2008 and to declare Abkhazia a "mine impact free" territory.[88]

The main NGO working in Abkhazia is the France-based international NGO Première-Urgence (PU)[89]: PU has been implementing rehabilitation and economical revival programmes to support the vulnerable populations affected by the frozen conflict for almost 10 years.

Geography and climate

Abkhazia covers an area of about 8,600 km² at the western end of Georgia. The Caucasus Mountains to the north and the northeast divide Abkhazia from the Russian Federation. To the east and southeast, Abkhazia is bounded by the Georgian region of Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti; and on the south and southwest by the Black Sea.

Abkhazia is extremely mountainous. The Greater Caucasus Mountain Range runs along the region's northern border, with its spurs – the Gagra, Bzyb and Kodori ranges – dividing the area into a number of deep, well-watered valleys. The highest peaks of Abkhazia are in the northeast and east and several exceed 4,000 meters (13,120 ft) above sea level. The landscapes of Abkhazia range from coastal forests and citrus plantations, to eternal snows and glaciers to the north of the region. Although Abkhazia's complex topographic setting has spared most of the territory from significant human development, its cultivated fertile lands produce tea, tobacco, wine and fruits, a mainstay of the local agricultural sector.

Abkhazia is richly irrigated by small rivers originating in the Caucasus Mountains. Chief of these are: Kodori, Bzyb, Ghalidzga, and Gumista. The Psou River separates the region from Russia, and the Inguri serves as a boundary between Abkhazia and Georgia proper. There are several periglacial and crater lakes in mountainous Abkhazia. Lake Ritsa is the most important of them.

Because of Abkhazia's proximity to the Black Sea and the shield of the Caucasus Mountains, the region's climate is very mild. The coastal areas of the republic have a subtropical climate, where the average annual temperature in most regions is around 15 degrees Celsius. The climate at higher elevations varies from maritime mountainous to cold and summerless. Abkhazia receives high amounts of precipitation, but its unique micro-climate (transitional from subtropical to mountain) along most of its coast causes lower levels of humidity. The annual precipitation vacillates from 1,100-1,500 mm (43-59 inches) along the coast to 1,700-3,500 mm (67-138 in.) in the higher mountainous areas. The mountains of Abkhazia receive significant amounts of snow.

There are two border crossings into Abkhazia. The southern border crossing is at the Inguri bridge, a short distance from the Georgian city of Zugdidi. The northern crossing ("Psou") is in the town of Gyachrypsh. Owing to the ongoing security situation, many foreign governments advise their citizens against travelling to Abkhazia.[90]

Government and Administration

In Soviet times Abkhaz ASSR was divided into 6 raions or districts named after their centres: Gagra, Gudauta, Sukhumi, Ochamchira, Gulripsh and Gali. The de jure division of Abkhazian Autonomous Republic of Georgia remained the same (see here).

The administrative division of the unrecognised Republic of Abkhazia is the same with one exception - a new Tkvarcheli raion was carved from the Ochamchire and Gali raions in 1995.

The President of the Republic appoints districts' heads from those elected to the districts' assemblies. There are elected village assemblies whose heads are appointed by the districts' heads.[39]

The People's Assembly, consisting of 35 elected members, is vested with legislative powers. The last parliamentary elections were held on 4 March 2007. The ethnicities other than Abkhaz (Armenians, Russians and Georgians) are believed to be under-represented in the Assembly as the number of the parliamentarians of these ethnicities is less than their share in the republic population.[39]

About 250,000 ethnic Georgian residents of Abkhazia are restricted from settling in the region by the Abkhazian regime and cannot participate in the elections.[91]

Abkhazian officials have stated that they have given the Russian Federation the responsibility of representing their interests abroad.[92]

Government of the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia

The Government of the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia is a government in exile that Georgia recognizes as the only legitimate government of Abkhazia. It had governed Upper Abkhazia between September 2006 and July 2008. It was forced out of all of Abkhazia in the 2008 South Ossetia war.

Military

The Abkhazian Armed Forces is the military of the Republic of Abkhazia. The basis of the Abkhazian armed forces was the ethnic Abkhaz National Guard formed early in 1992. Most of the weapons come from the Russian airborne division base in Gudauta. The Abkhaz military is primarily a ground force but includes small sea and air units.

The Abkhazian Armed Forces is composed of:

- The Abkhazian Land Forces with a permanent force of around 5,000 but may increase to reservists and paramilitary personnel of up to 50,000 in times of military conflict. The exact numbers and equipment used remain unverifiable.

- The Abkhazian Navy that consists of three divisions that are based in Sukhumi, Ochamchire and Pitsunda.

- The Abkhazian Air Force, a small unit and reported number of fighter aircrafts and helicopters

Economy

The economy of Abkhazia is heavily integrated with Russia and uses the Russian ruble as its currency. Tourism is a key industry and the Abkhaz de facto authorities claim that the organised tourists (mainly from Russia) numbered more than 100,000 in recent years, compared to about 200,000 in the 1990 before the war.[93] The number of visitors in 2006 was estimated by Abkhazian authorities to have been approximately 1.5 million.[94] Although Russia has established a visa regime with Georgia, Russian passport-holders do not require a visa to enter Abkhazia. Holders of European Union passports require an Entry Permit Letter issued by the de facto Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Sukhumi, against which a visa will be issued upon presentation of the Letter to the MFA.[95]

Abkhazia's fertile land and abundance of agricultural products, including tea, tobacco, wine and fruits (especially tangerines), have secured a relative stability in the sector. Electricity is largely supplied by the Inguri hydroelectric power station located on the Inguri River between Abkhazia and Georgia proper and operated jointly by Abkhaz and Georgians.

The exports and imports in 2006 were 627.2 and 3270.2 mln. rubles respectively (appx. 22 and 117 mln. US dollars) according to the Abkhazian authorities.[96]

Many Russian entrepreneurs and some Russian municipalities have invested or plan to invest in Abkhazia. This includes the Moscow municipality after the Mayor of Moscow, Yury Luzhkov, signed an agreement on economic cooperation between Moscow and Abkhazia. Both Abkhaz and Russian officials have announced their intentions to exploit Abkhazia's facilities and resources for the Olympic construction projects in Sochi, as the city will host the 2014 Winter Olympics. The Government of Georgia has warned against such actions, however,[97] and has threatened to ask foreign banks to close accounts of Russian companies and individuals that buy assets in Abkhazia.[98]

According to the U.S.-based organisation Freedom House, the region continues to suffer considerable economic problems owing to widespread corruption, the control by criminal organizations of large segments of the economy, and the continuing effects of the war.[99]

The CIS economic sanctions imposed on Abkhazia in 1996 are still formally in force although Russia announced on 6 March 2008 that it would no longer participate in them, declaring them "outdated, impeding the socio-economic development of the region, and causing unjustified hardship for the people of Abkhazia". Russia also called on other CIS members to undertake similar steps,[100] but met with protests from Tbilisi and lack of support from the other CIS countries.[101]

The European Union has allocated more than €20 mln. to Abkhazia since 1997 for various humanitarian projects, including the support of civil society, economic rehabilitation, help to the most vulnerable households and confidence building measures. The single largest EU's project is the repair and reconstruction of the Inguri power station.[102]

Demographics

The population of Abkhazia is mostly ethnic Abkhaz, Georgians (including Mingrelians), Armenians, and Russians. Prior to the 1992-1993 War, ethnic Georgians made up almost half of Abkhazia's population, while the Abkhaz accounted for less than one-fifth. However, by 1993, most Georgians and some Russians and Armenians had fled Abkhazia[103] following a war and the ethnic cleansing of Georgians in Abkhazia. As a result, the population of Abkhazia dropped abruptly from more than 500,000 at the time of the 1989 census to approximately 200,000 in 1994-1995.[104]

The earliest reliable records for Abkhazia are the Family Lists compiled in 1886 (published 1893 in Tbilisi), according to which the Sukhumi District's population was 68,773, of which 30,640 were Samurzaq'anoans, 28,323 Abkhaz, 3,558 Mingrelians, 2,149 Greeks, 1,090 Armenians, 1,090 Russians and 608 Georgians[105] (including Imeretians and Gurians). Samurzaq'ano is a present-day Gali district of Abkhazia. Most of the Samurzaq'anians must be thought to have been Mingrelians, and a minority Abkhaz.[28][106]

According to the 1897 census there were 58,697 people in Abkhazia who listed Abkhaz as their mother tongue.[107] The population of the Sukhumi district (Abkhazia) was about 100,000 at that time. Greeks, Russians and Armenians composed 3.5%, 2% and 1.5% of the district's population.[108] According to the 1917 agricultural census organized by the Russian Provisional Government, Georgians and Abkhaz composed 41.7% (54,760) and 30,4% (39,915) of the rural population of Abkhazia respectively.[109] At that time Gagra and its vicinity were not part of Abkhazia.

The following table summarises the results of the other censuses carried out in Abkhazia. The Russian, Armenian and Georgian population grew faster than Abkhaz, due to the large-scale migration enforced especially during the rule of Stalin and Lavrenty Beria, who himself was a Georgian born in Abkhazia.[110] About 2,000 people (predominantly Svans, a subethnic group of the Georgian people) lived in Upper Abkhazia.

| Year | Georgians | Abkhaz | Russians | Armenians | Greeks | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1926 Census | 36.3% (67,494) |

30.1% (55,918) |

6.7% (12,553) |

13.8% (25,677) |

7.6% (14,045) |

186,004 |

| 1939 Census | 29.5% (91,967) |

18.0% (56,197) |

19.3% (60,201) |

15.9% (49,705) |

11.1% (34,621) |

311,885 |

| 1959 Census | 39.1% (158,221) |

15.1% (61,193) |

21.4% (86,715) |

15.9% (64,425) |

2.2% (9,101) |

404,738 |

| 1970 Census | 41.0% (199,596) |

15.9% (77,276) |

19.1% (92,889) |

15.4% (74,850) |

2.7% (13,114) |

486,959 |

| 1979 Census | 43.9% (213,322) |

17.1% (83,087) |

16.4% (79,730) |

15.1% (73,350) |

2.8% (13,642) |

486,082 |

| 1989 Census | 45.7% (239,872) |

17.8% (93,267) |

14.3% (74,913) |

14.6% (76,541) |

2.8% (14,664) |

525,061 |

| 2003 Census[105] | 21.3% (45,953) |

43.8% (94,606) |

10.8% (23,420) |

20.8% (44,870) |

0.7% (1,486) |

215,972 |

Georgia contests the results of the 2003 population census in Abkhazia. The Department of Statistics of Georgia estimated Abkhazia's population to be approximately 190,000 in 1998, 179,000 in 2003 (the census year), and 178,000 in 2005 (the last year when such estimates were published in Georgia).[104] Encyclopædia Britannica estimates the population in 2007 at 180,000[103] and the International Crisis Group estimates Abkhazia's total population in 2006 to be between 157,000 and 190,000 (or between 180,000 and 220,000 as estimated by UNDP in 1998).[111] The discrepancy of 30,000-40,000 between the contested 2003 population census and the alternative estimates pales compared with the huge drop of more than 300,000 in Abkhazia's total population since the 1989 census.[104] Comparison between the 1989 and 2003 censuses shows that the number of Abkhaz hardly changed and the decline in total population is attributable to the exodus of Georgians, as well as Russians, Armenians, and Greeks.

|

|||||||||||

Religion

The population (including all ethnic groups) of Abkhazia are Orthodox Christians (Abkhaz, Georgians, Russians), Armenian Apostolic Christians (ethnic Armenians), and a Sunni Muslim minority (mostly ethnic Abkhaz).[112] However, many of the people who declare themselves Christian or Muslim do not attend religious services. There is also a very small number of Jews, Jehovah's Witnesses and the followers of new religions.[113] The Jehovah's Witnesses organization has officially been banned since 1995, though the decree is not currently enforced.[114]

According to the constitutions of Georgia, Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia and de facto Republic of Abkhazia the adherents of all religions (as well as atheists) have equal rights before the law.[115] Muslims' rights are respected, however Christian Georgians and Armenians face harassment and persecution according to the Freedom House's May 2007 report.[116]

Abkhazia is recognized by the Eastern Orthodox world as a canonical territory of the Georgian Orthodox Church, which has been unable to operate in the region since the War in Abkhazia. Currently, the religious affairs of local Orthodox Christian community is run by the self-imposed "Eparchy of Abkhazia" under significant influence of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Culture

The written Abkhaz literature appeared relatively recently, in the beginning of the 20th century. However, Abkhaz share with other Caucasian peoples the Nart sagas — series of tales about mythical heroes. The Abkhaz alphabet was created in the 19th century. The first newspaper in Abkhaz, called Abkhazia and edited by Dmitry Gulia, appeared in 1917.

Arguably the most famous Abkhaz writers are Fazil Iskander, who wrote mostly in Russian and Bagrat Shinkuba a poet.

Football remains the most popular sport in Abkhazia. Other popular sports include basketball, boxing, wrestling.

Abkhazia has its own amateur Abkhazian football league since 1994. The league is not a part of any international football union.

Gallery of Abkhazia

See also

- Law enforcement in Abkhazia

- Armenians in Abkhazia

- South Ossetia

- Transnistria

- Commonwealth of Unrecognized States

- Controversy over Abkhazian and South Ossetian independence

References

- ↑ http://www.abkhaziagov.org/ru/state/sovereignty/independence.php

- ↑ http://www.apsnypress.info/news2008/September/22.htm

- ↑ http://www.unpo.org/content/view/713/236/

- ↑ Olga Oliker, Thomas S. Szayna. Faultlines of Conflict in Central Asia and the South Caucasus: Implications for the U.S. Army. Rand Corporation, 2003, ISBN 0833032607

- ↑ Abkhazia: ten years on. By Rachel Clogg, Conciliation Resources, 2001

- ↑ Medianews.ge. Training of military operations underway in Abkhazia, 21 August 2007

- ↑ Emmanuel Karagiannis. Energy and Security in the Caucasus. Routledge, 2002. ISBN 0700714812

- ↑ GuardianUnlimited. Georgia up in arms over Olympic cash

- ↑ International Relations and Security Network. Kosovo wishes in Caucasus. By Simon Saradzhyan

- ↑ "Абхазия, Южная Осетия и Приднестровье признали независимость друг друга и призвали всех к этому же". Newsru (2006-11-17). Retrieved on 2008-08-26.

- ↑ CNN, Tensions build as U.S. ship arrives in Georgia, 28 August 2008

- ↑ West condemns Russia over Georgia, BBC, 26 August 2008

- ↑ Scheffer ‘Rejects’ Russia’s Move, Civil.ge, 26 August 2008

- ↑ CoE, PACE Chairs Condemn Russia’s Move, Civil Georgia, 26 August 2008

- ↑ OSCE Chair Condemns Russia’s Recognition of Abkhazia, S.Ossetia, Civil Georgia, 26 August 2008

- ↑ Resolution of the Parliament of Georgia declaring Abkhazia and South Ossetia occupied territories, 28 August 2008.

- ↑ Abkhazia, S.Ossetia Formally Declared Occupied Territory. Civil Georgia. 2008-08-28

- ↑ Russia: Georgia can 'forget' regaining provinces [The Associated Press], DAVID NOWAK and CHRISTOPHER TORCHIA 14 August 2008

- ↑ Houtsma, M. Th.; E. van Donzel (1993). E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936. BRILL. pp. 71. ISBN 9004097961. http://books.google.com/books?id=GEl6N2tQeawC&pg=PA70&dq=Abkhazia+history+19th+century&lr=&as_brr=3&ei=9M_YSKfxHITkygT43eHrDg&hl=ru&sig=ACfU3U3EI2n5q0igEzSDGdeA-Y3_Nj6UVA#PPA71,M1.

- ↑ Lortkipanidze M., The Abkhazians and Abkhazia, Tbilisi 1990.

- ↑ Abkhazia Today. The International Crisis Group. Europe Report N°176 – 15 September 2006, page 4. Retrieved on 21 April 2007. Free registration needed to view full report

- ↑ Causes and Visions of Conflict in Abkhazia. Ghia Nodia, 1997, page 27. Retrieved on 5 August 2007.

- ↑ 1925 Constitution of SSR Abkhazia: definition of status (Article 3)

- ↑ Neproshin A.Ju. Russian: Абхазия. Проблемы международного признания MGIMO, 16-17 May 2006

- ↑ Conciliation Resources. Georgia-Abkhazia, Chronology

- ↑ Парламентская газета (Parlamentskaya Gazeta). Референдум о сохранении СССР. Грузия строит демократию на беззаконии. Георгий Николаев, 17 March 2006 (Russian)

- ↑ 1921 Constitution of the Democratic Republic of Georgia: Chapter XI, Articles 107-108 (adopted by the Constituent Assembly of Georgia February 21, 1921): "Abkhasie (district of Soukhoum), ..., which are integral parts of the Georgian Republic, enjoy autonomy in the administration of their affairs. The statute concerning the autonomy of [these] districts ... will be the object of special legislation". Regional Research Center. Retrieved on 2008-11-25.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Svante E. Cornell (2001), Small Nations and Great Powers: A Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus, pp. 345-9. Routledge, ISBN 0700711627.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 On Ruins of Empire: Ethnicity and Nationalism in the Former Soviet Union, pg 72, by Georgiy I. Mirsky, published by Greenwood Publishing Group, sponsored by the London School of Economics

- ↑ Full Report by Human Rights Watch. Human Rights Watch. Georgia/Abkhazia. Violations of the laws of war and Russia's role in the conflict Helsinki, March 1995. p. 22

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 Full Report by Human Rights Watch. Human Rights Watch. Georgia/Abkhazia. Violations of the laws of war and Russia's role in the conflict Helsinki, March 1995

- ↑ Chervonnaia, Svetlana Mikhailovna. Conflict in the Caucasus: Georgia, Abkhazia, and the Russian Shadow. Gothic Image Publications, 1994, Introduction

- ↑ CSCE Budapest Document 1994, Budapest Decisions, Regional Issues

- ↑ Lisbon OSCE Summit Declaration

- ↑ Istanbul OSCE Summit Declaration

- ↑ Commonwealth and Independence in Post-Soviet Eurasia Commonwealth and Independence in Post-Soviet Eurasia by Bruno Coppieters, Alekseĭ Zverev, Dmitriĭ Trenin, p 61

- ↑ UN High Commissioner for refugees. Background note on the Protection of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Georgia remaining outside Georgia, cached version

- ↑ Report of the Representative of the Secretary-General on the human rights of internally displaced persons – Mission to Georgia. United Nations: 2006.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 Abkhazia Today. The International Crisis Group Europe Report N°176, 15 September 2006, page 10. Retrieved on 30 May 2007. Free registration needed to view full report

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/3261059.stm

- ↑ http://www.airforcetimes.com/news/2008/04/airforce_georgian_uav_042208/

- ↑ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AfRHMbz2nuU

- ↑ Russia in operation to storm Abkhazia gorge

- ↑ http://www.russiatoday.com/news/news/29521

- ↑ Belarus says to recognise Abkhazia, S. Ossetia by weekend

- ↑ Diplomat: Belarus to recognise Abkhazia, South Ossetia soon

- ↑ Chavez Backs Russian Recognition of Georgian Regions Reuters. Retrieved 08-29, 2008

- ↑ Chervonnaia, Svetlana Mikhailovna. Conflict in the Caucasus: Georgia, Abkhazia, and the Russian Shadow. Gothic Image Publications, 1994.

- ↑ The Abkhazia Conflict. U.S. Department of State Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs. 28 July 2005.

- ↑ Vladimir Socor (7 February 2006), Moscow kills Boden paper, threatens to terminate UNOMIG in Georgia. Eurasia Daily Monitor, Volume 3, Number 26.

- ↑ Breakaway Abkhazia seeks recognition, Al-Jazeera, 18 October 2006.

- ↑ UN Security Council Resolution 1808. 15 April 2008.

- ↑ Resolution of the OSCE Budapest Summit, OSCE, 1994-12-06

- ↑ General Assembly Adopts Resolution Recognizing Right Of Return By Refugees, Internally Displaced Persons To Abkhazia, Georgia

- ↑ Georgia-Abkhazia: Profiles. Accord: an international review of peace initiatives. Reconciliation Resources. Accessed on 2 April 2007.

- ↑ GENERAL ASSEMBLY ADOPTS RESOLUTION RECOGNIZING RIGHT OF RETURN BY REFUGEES, INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS TO ABKHAZIA, GEORGIA, 15.05.2008

- ↑ Saakashvili Outlines Tbilisi’s Abkhaz Initiatives. Civil Georgia. 2008-03-28.

- ↑ Burjanadze: Russia Behind Sokhumi’s No to New Proposals. Civil Georgia. 2008-03-29.

- ↑ OSCE PA Concerned over Russian Moves Civil Georgia. 3 July 2008.

- ↑ Press conference of Sergey Shamba, Moskovskiy Komsomolets, 6 July 2006 (Russian)

- ↑ "К концу 2007 года 90 процентов граждан Абхазии должны получить "национальные" паспорта — Президент", abkhaziagov.org, 29 May 2007 (Russian)

- ↑ UNOMIG, RECOGNITION MAY COME "THIS YEAR", SOUTH OSSETIA'S LEADER SAYS - REPORT, 21.02.08

- ↑ Georgia angered by Russian move. BBC News. 16 April 2008.

- ↑ In Quotes: International Reaction to Russia’s Abkhaz, S.Ossetian Move. Civil Georgia. 19 April 2008.

- ↑ Georgia-Russia tensions ramped up.. The BBC News. 30 April 2008.

- ↑ "Russia to recognise breakaway region's independence", The Times (2008-08-20). Retrieved on 2008-08-20.

- ↑ "Duma calls for S. Ossetia independence". Financial Times (2008-08-25). Retrieved on 2008-08-25.

- ↑ BBC News: "Russia recognises Georgian rebels", 26 August 2008.

- ↑ Russia recognizes independence of Georgia's rebel regions, Earth Times, 2008-08-26, accessed on 2008-08-26

- ↑ http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/main/news/12661/

- ↑ West condemns Russia over Georgia, BBC, 26 August 2008

- ↑ Scheffer ‘Rejects’ Russia’s Move, Civil.ge, 26 August 2008

- ↑ CoE, PACE Chairs Condemn Russia’s Move, Civil Georgia, 26 August 2008

- ↑ OSCE Chair Condemns Russia’s Recognition of Abkhazia, S.Ossetia, Civil Georgia, 26 August 2008

- ↑ Tensions build as U.S. ship arrives in Georgia, CNN, 29 August 2008

- ↑ West condemns Russia over Georgia, BBC, 26 August 2008

- ↑ Civil.ge, CoE, PACE Chairs Condemn Russia’s Move, 26.08.08

- ↑ "Why I had to recognise Georgia's breakaway regions". Financial Times. Retrieved on 2008-09-13.

- ↑ United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244 S-RES-1244(1999) page 2 on 10 June 1999 (retrieved 2008-09-04)

- ↑ Resolving Georgian crisis may be harder after Russian recognition move – Ban UN News Centre

- ↑ Resolutions 849, 854, 858, 876, 881 and 892 adopted by the UN Security Council

- ↑ From the Resolution of the OSCE Budapest Summit, 6 December 1994 LISBON OSCE SUMMIT DECLARATION

- ↑ Lisbon Summit Declaration of the OSCE, 2-3 December 1996

- ↑ U.S. Senator Urges Russian Peacekeepers’ Withdrawal From Georgian Breakaway Republics. (MosNews).

- ↑ Solana fears Kosovo 'precedent' for Abkhazia, South Ossetia. (International Relations and Security Network).

- ↑ Russia 'not neutral' in Black Sea conflict, EU says, EUobserver, 10 October 2006.

- ↑ SECURITY COUNCIL EXTENDS GEORGIA MISSION UNTIL 15 APRIL 2007, The UN Department of Public Information, 13 October 2006.

- ↑ The HALO Trust. Abkhazia

- ↑ Première-Urgence NGO, France

- ↑ Travel advice by country: Georgia. The United Kingdom Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Retrieved on 2 July 2007; Consular Information Sheet: Georgia. The U.S. Department of State. Retrieved from Allsafetravels.com on 2 July 2007; Travel advisories: Georgia. Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, New Zealand. Retrieved from Allsafetravels.com on 2 July 2007; Travel advice: Georgia. Australian Government, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Retrieved from Allsafetravels.com on 2 July 2007; Travel advice: Georgia, Irish Government, Department of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved on 2 July 2007.

- ↑ * Zarkovic Bookman, Milica (1997). The Demographic Struggle for Power: The Political Economy of Demographic Engineering in the Modern World. ISBN 0714647322.

- ↑ "Kremlin announces that South Ossetia will join 'one united Russian state'". Times online. Retrieved on 03 September, 2008.

- ↑ Civil.ge, Abkhazia’s Beauty out of Sight, 22.08.2003

- ↑ Rosbalt.ru, Багапш: Все больше туристов приезжает в Абхазию (Bagapsh: More and more tourists come to Abkhazia), 01.09.2006 (Russian)

- ↑ Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Abkhazia :: Consular Service

- ↑ National Bank of the Republic of Abkhazia, Основные показатели развития экономики и банковского сектора Республики Абхазия за 2006 год (Main indicators of the economy and banking industry of the Republic of Abkhazia, 2006) (Russian)

- ↑ Statement of the Ministry of Environment Protection and Natural Resources of Georgia. OSCE Economic and Environmental Summit, Prague, May 2008.

- ↑ Moscow Mayor Pledges More Investment in Abkhazia, Civil Georgia. 9 July 2007.

- ↑ Country Report 2007: Abkhazia (Georgia). The Freedom House. Accessed on 3 October 2007.

- ↑ "Russian Federation Withdraws from Regime of Restrictions Established in 1996 for Abkhazia". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia (2008-03-06). Retrieved on 2008-03-06.

- ↑ Russia expands economic ties with Abkhazia, Georgia angry, CIS idle. Itar-Tass, 09.04.2008.

- ↑ The European Commission's Delegation to Georgia, Overview of EC Assistance in Abkhazia & South Ossetia

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 "Abkhazia." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 09 Sep. 2008.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 104.2 Statistical Yearbook of Georgia 2005: Population, Table 2.1, p. 33, Department for Statistics, Tbilisi (2005)

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 Population censuses in Abkhazia: 1886, 1926, 1939, 1959, 1970, 1979, 1989, 2003 (Russian) Georgian and Mingrelian figures have been conflated, as most of the "Georgians" were ethnically Mingrelian.

- ↑ Müller, D, 1999. Demography: ethno-demographic history, 1886-1989 in The Abkhazians: A handbook. Richmond: Curzon Press.

- ↑ 1-я Всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. Кутаисская губерния. Спб: 1905. С. 32б retrieved from "АБХАЗИЯ-1992: ПОСТОКОММУНИСТИЧЕСКАЯ ВАНДЕЯ" by Svetlana Chervonnaya

- ↑ Sukhum in Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (Russian)

- ↑ Ментешашвили А.М. Исторические предпосылки современного сепаратизма в Грузии. - Тбилиси, 1998.

- ↑ JRL RESEARCH & ANALYTICAL SUPPLEMENT ~ JRL 8226, Issue No. 24 • May 2004. SPECIAL ISSUE; THE GEORGIAN-ABKHAZ CONFLICT: PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE

- ↑ Abkhazia Today. The International Crisis Group Europe Report N°176, 15 September 2006, page 9. Free registration needed to view full report

- ↑ Olson, James Stuart; Lee Brigance Pappas, Nicholas Charles Pappas (1994). An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 9. ISBN 0313274975.

- ↑ Александр Крылов. ЕДИНАЯ ВЕРА АБХАЗСКИХ "ХРИСТИАН" И "МУСУЛЬМАН". Особенности религиозного сознания в современной Абхазии.

- ↑ Georgia: International Religious Freedom Report 2005. The United States Department of State. Retrieved on 24 May 2007.

- ↑ Constitution of the Republic of Abkhazia, art. 12 (Russian)

- ↑ Karatnycky, Adrian (2000). Freedom in the World: The Annual Survey of Political Rights and Civil Liberties. Transaction Publishers. pp. 550. ISBN 0765807602.

External links

- (English) Abkhazia and South Ossetia maps : Georgia's rebel regions maps Abkhazia ussr.

- (English)/(Russian)/(Georgian) Government of the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia. Official web-page

- (English)/(Russian)/(Turkish)/(Abkhaz) President of the Republic of Abkhazia. Official site

- (English)/ Institute for Social and Economic Research

- (English)/(Russian)/(Turkish) Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Abkhazia. Official Site

- (English) BBC Regions and territories: Abkhazia

- (English) The Autonomous Republic of Abkhazeti - from Georgian National Parliamentary Library

- (English) Abkhazia.com Official website of the refugees from Abkhazia

- (Russian) State Information Agency of the Abkhaz Republic

- (English) Abkhazia Provisional Paper Money

- (Russian) Orthodox Churches of Abkhazia

- (English) Abkhazia and South Ossetia: Georgia's rebel regions news portal

- (Russian) Archaeology and ethnography of Abkhazia. Abkhaz Institute of Social Studies. Abkhaz State Museum

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||