Eclipse

An eclipse is an astronomical event that occurs when one celestial object moves into the shadow of another. The term is derived from the ancient Greek noun ἔκλειψις (ékleipsis), from verb ἐκλείπω (ekleípō), "I cease to exist," a combination of prefix ἐκ- (ek-), from preposition ἐκ, ἐξ (ek, ex), "out," and of verb λείπω (leípō), "I am absent".[1] When an eclipse occurs within a stellar system, such as the Solar System, it forms a type of syzygy—the alignment of three or more celestial bodies in the same gravitational system along a straight line.[2]

The term eclipse is most often used to describe either a solar eclipse, when the Moon's shadow crosses the Earth's surface, or a lunar eclipse, when the Moon moves into the shadow of Earth. However, it can also refer to such events beyond the Earth-Moon system: for example, a planet moving into the shadow cast by one of its moons, a moon passing into the shadow cast by its parent planet, or a moon passing into the shadow of another moon. A binary star system can also produce eclipses if the plane of their orbit intersects the position of the observer.

Contents |

Syzygy

A syzygy is the alignment of three or more celestial bodies in the same gravitational system along a straight line. The word is usually used in context with the Sun, Earth, and the Moon or a planet, where the latter is in conjunction or opposition. Solar and lunar eclipses occur at times of syzygy, as do transits and occultations.

An eclipse occurs when there is a syzygy between a star and two celestial bodies, such as a planet and a moon. The shadow cast by the object closest to the star intersects the more distant body, lowering the amount of luminosity reaching the latter's surface. The region of shadow cast by the occulting body is divided into an umbra, where the radiation from the star's radiation-emitting photosphere is completely blocked, and a penumbra, where only a portion of the radiation is blocked.[3]

A total eclipse will occur when the observer is located within the umbra of the occulting object. Totality occurs at the point of maximum phase during a total eclipse, when the occulted object is completely covered. When the star and a smaller occulting object are nearly spherical, the umbra forms a cone-shaped region of shadow in space.

Beyond the end of the umbra is a region called the antumbra, where a planet or moon will be seen transiting across the star but not completely covering it. For an observer inside the antumbra of a solar eclipse, for example, the Moon appears smaller than the Sun, resulting in an annular eclipse.[3] The remaining volume of shadowed space, where only a fraction of the occulting object overlaps the star, is called the penumbra. An eclipse that does not reach totality, such as when the observer is in the penumbra, is called a partial eclipse.

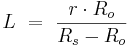

For spherical bodies, when the occluding object is smaller than the star, the length (L) of the Umbra's cone-shaped shadow is given by:

where Rs is the radius of the star, Ro is the occulting object's radius, and r is the distance from the star to the occulting object. For Earth, on average L is equal to 1.384×106 km, which is much larger than the Moon's semimajor axis of 3.844×105 km. Hence the umbral cone of the Earth can completely envelop the Moon during a lunar eclipse.[4] If the occulting object has an atmosphere, however, some of the luminosity of the star can be refracted into the volume of the umbra. This occurs, for example, during an eclipse of the Moon by the Earth—producing a faint, ruddy illumination of the Moon even at totality.

An astronomical transit is also a type of syzygy, but is used to describe the situation where the nearer object is considerably smaller in apparent size than the more distant object. Likewise, an occultation is a syzygy where the apparent size of the nearer object appears much larger than the distant object, and the distant object becomes completely hidden during the event.

An eclipse cycle takes place when a series of eclipses are separated by a certain interval of time. This happens when the orbital motions of the bodies form repeating harmonic patterns. A particular instance is the Saros cycle, which results in a repetition of a solar or lunar eclipse every 6,585.3 days, or a little over 18 years. However, because this cycle has an odd number of days, a successive eclipse is viewed from a different part of the world.[5]

Earth-Moon System

An eclipse involving the Sun, Earth and Moon can occur only when they are nearly in a straight line, allowing the shadow cast by the Sun to fall upon the eclipsed body. Because the orbital plane of the Moon is tilted with respect to the orbital plane of the Earth (the ecliptic), eclipses can occur only when the Moon is close to the intersection of these two planes (the nodes). The Sun, Earth and nodes are aligned twice a year, and eclipses can occur during a period of about two months around these times. There can be from four to seven eclipses in a calendar year, which repeat according to various eclipse cycles, such as the Saros cycle.

Solar eclipse

An eclipse of the Sun by the Moon is termed a solar eclipse. Records of solar eclipses have been kept since ancient times. A Syrian clay tablet records a solar eclipse on March 5, 1223 BCE,[6] while Paul Griffin argues that a stone in Ireland records an eclipse on November 30, 3340 BCE.[7] Chinese historical records of solar eclipses date back over 4,000 years and have been used to measure changes in the Earth's rate of spin.[8] Eclipse dates can also be used for chronological dating of historical records.

The type of solar eclipse event depends on the distance of the Moon from the Earth during the event. A total solar eclipse occurs when the Earth intersects the umbra portion of the Moon's shadow. When the umbra does not reach the surface of the Earth, the Sun is only partially occluded, resulting in an annular eclipse. Partial solar eclipses occur when the viewer is inside the penumbra.[9]

The eclipse magnitude is the fraction of the Sun's diameter that is covered by the Moon. For a total eclipse, this value is always greater than or equal to one. In both annular and total eclipses, the eclipse magnitude is the ratio of the angular sizes of the Moon to the Sun.[10]

Solar eclipses are relatively brief events that can only be viewed in totality along a relatively narrow track. Under the most favorable circumstances, a total solar eclipse can last for 7 minutes, 31 seconds, and can be viewed along a track that is up to 250 km wide. However, the region where a partial eclipse can be observed is much larger. The Moon's umbra will advance eastward at a rate of 1,700 km/h, until it no longer intersects the Earth.

During a solar eclipse, the Moon can sometimes perfectly cover the Sun because its apparent size is nearly the same as the Sun when viewed from the Earth. A solar eclipse is actually a misnomer; the phenomenon is more correctly described as an occultation of the Sun by the Moon or an eclipse of the Earth by the Moon.

Lunar eclipse

Lunar eclipses occur when the Moon passes through the Earth's shadow. Since this occurs only when the Moon is on the far side of the Earth from the Sun, lunar eclipses only occur when there is a full moon. Unlike a solar eclipse, an eclipse of the Moon can be observed from nearly an entire hemisphere. For this reason it is much more common to observe a lunar eclipse from a given location. A lunar eclipse also lasts longer, taking several hours to complete, with totality itself usually averaging anywhere from about 30 minutes to over an hour.[11]

There are three types of lunar eclipses: penumbral, when the Moon crosses only the Earth's penumbra; partial, when the Moon crosses partially into the Earth's umbra; and total, when the Moon circles entirely within the Earth's umbra. Total lunar eclipses pass through all three phases. Even during a total lunar eclipse, however, the Moon is not completely dark. Sunlight refracted through the Earth's atmosphere intersects the umbra and provides a faint illumination. Much as in a sunset, the atmosphere tends to scatter light with shorter wavelengths, so the illumination of the Moon by refracted light has a red hue.[12]

Other planets

Eclipses are impossible on Mercury and Venus, which have no moons. However, both have been observed to transit across the face of the Sun. There are on average 13 transits of Mercury each century. Transits of Venus occur in pairs separated by an interval of eight years, but each pair of events happen less than once a century.[13]

On Mars, only partial solar eclipses are possible, because neither of its moons is large enough, at their respective orbital radii, to cover the Sun's disc as seen from the surface of the planet. Eclipses of the moons by Mars are not only possible, but commonplace, with hundreds occurring each Earth year. There are also rare occasions when Deimos is eclipsed by Phobos.[14] Martian eclipses have been photographed from both the surface of Mars and from orbit.

The gas giant planets (Jupiter,[15] Saturn,[16] Uranus,[17] and Neptune)[18] have many moons and thus frequently display eclipses. The most striking involve Jupiter, which has four large moons and a low axial tilt, making eclipses more frequent as these bodies pass through the shadow of the larger planet. Transits occur with equal frequency. It is common to see the larger moons casting circular shadows upon Jupiter's cloudtops.

The eclipses of the Galilean moons by Jupiter became accurately predictable once their orbital elements were known. During the 1670s, it was discovered that these events were occurring about 17 minutes later than expected when Jupiter was on the far side of the Sun. Ole Rømer deduced that the delay was caused by the time needed for light to travel from Jupiter to the Earth. This was used to produce the first estimate of the speed of light.[19]

On the other three gas giants, eclipses only occur at certain periods during the planet's orbit, due to their higher inclination between the orbits of the moon and the orbital plane of the planet. The moon Titan, for example, has an orbital plane tilted about 1.6° to Saturn's equatorial plane. But Saturn has an axial tilt of nearly 27°. The orbital plane of Titan only crosses the line of sight to the Sun at two points along Saturn's orbit. As the orbital period of Saturn is 29.7 years, an eclipse is only possible about every 15 years.

The timing of the Jovian satellite eclipses was also used to calculate an observer's longitude upon the Earth. By knowing the expected time when an eclipse would be observed at a standard longitude (such as Greenwich), the time difference could be computed by accurately observing the local time of the eclipse. The time difference gives the longitude of the observer because every hour of difference corresponded to 15° around the Earth's equator. This technique was used, for example, by Giovanni D. Cassini in 1679 to re-map France.[20]

Pluto, with its proportionately large moon Charon, is also the site of many eclipses. A series of such mutual eclipses occurred between 1985 and 1990.[21] These daily events led to the first accurate measurements of the physical parameters of both objects.[22]

Eclipsing binaries

A binary star system consists of two stars that orbit around their common center of mass. The movements of both stars lie on a common orbital plane in space. When this plane is very closely aligned with the location of an observer, the stars can be seen to pass in front of each other. The result is a type of extrinsic variable star system called an eclipsing binary.

The maximum luminosity of an eclipsing binary system is equal to the sum of the luminosity contributions from the individual stars. When one star passes in front of the other, the luminosity of the system is seen to decrease. The luminosity returns to normal once the two stars are no longer in alignment.[23]

The first eclipsing binary star system to be discovered was Algol, a star system in the constellation Perseus. Normally this star system has a visual magnitude of 2.1. However, every 20.867 days the magnitude decreases to 3.4 for more than 9 hours. This is caused by the passage of the dimmer member of the pair in front of the brighter star.[24] The concept that an eclipsing body caused these luminosity variations was introduced by John Goodricke in 1783.[25]

See also

- Eclipse cycle

- Mursili's eclipse

- Saros cycle

- Syzygy

References

- ↑ Liddell; Scott, Robert (1940). "A Greek-English Lexicon". The National Science Foundation. Retrieved on 2007-12-13.

- ↑ The New York Times (March 31, 1981). "Science Watch: A Really Big Syzygy". Press release. Retrieved on 2008-02-29.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Espenak, Fred (September 21, 2007). "Glossary of Solar Eclipse Terms". NASA. Retrieved on 2008-02-28.

- ↑ Green, Robin M. (1985). Spherical Astronomy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0521317797.

- ↑ Espenak, Fred (July 12, 2007). "Eclipses and the Saros". NASA. Retrieved on 2007-12-13.

- ↑ de Jong, T.; van Soldt, W. H. (1989). "The earliest known solar eclipse record redated". Nature 338: 238–240. doi:. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v338/n6212/abs/338238a0.html. Retrieved on 2007-05-02.

- ↑ Griffin, Paul (2002). "Confirmation of World's Oldest Solar Eclipse Recorded in Stone". The Digital Universe. Retrieved on 2007-05-02.

- ↑ "Solar Eclipses in History and Mythology". Bibliotheca Alexandrina. Retrieved on 2007-05-02.

- ↑ Hipschman, R.. "Solar Eclipse: Why Eclipses Happen". Retrieved on 2008-12-01.

- ↑ Zombeck, Martin V. (2006). Handbook of Space Astronomy and Astrophysics (Third edition ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 48. ISBN 0521782422.

- ↑ Staff (January 6, 2006). "Solar and Lunar Eclipses". NOAA. Retrieved on 2007-05-02.

- ↑ Phillips, Tony (February 13, 2008). "Total Lunar Eclipse". NASA. Retrieved on 2008-03-03.

- ↑ Espenak, Fred (May 29, 2007). "Planetary Transits Across the Sun". NASA. Retrieved on 2008-03-11.

- ↑ Davidson, Norman (1985). Astronomy and the Imagination: A New Approach to Man's Experience of the Stars. Routledge. ISBN 0710203713.

- ↑ "Start eclipse of the Sun by Callisto from the center of Jupiter". JPL Solar System Simulator (2009-Jun-03 00:28 UT). Retrieved on 2008-06-05.

- ↑ "Eclipse of the Sun by Titan from the center of Saturn". JPL Solar System Simulator (2009-Aug-03 02:46 UT). Retrieved on 2008-06-05.

- ↑ "Brief Eclipse of the Sun by Miranda from the center of Uranus". JPL Solar System Simulator (2007-Jan-22 19:58 UT (JPL Horizons S-O-T=0.0565)). Retrieved on 2008-06-05.

- ↑ "Transit of the Sun by Nereid from the center of Neptune". JPL Solar System Simulator (2006-Mar-28 20:19 UT (JPL Horizons S-O-T=0.0079)). Retrieved on 2008-06-05.

- ↑ "Roemer's Hypothesis". MathPages. Retrieved on 2007-01-12.

- ↑ Cassini, Giovanni D. (1694). "Monsieur Cassini His New and Exact Tables for the Eclipses of the First Satellite of Jupiter, Reduced to the Julian Stile, and Meridian of London". Philosophical Transactions 18: 237–256. doi:. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0260-7085(1694)18%3C237%3AMCHNAE%3E2.0.CO%3B2-W. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ↑ Buie, M. W.; Polk, K. S. (1988). "Polarization of the Pluto-Charon System During a Satellite Eclipse". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society 20: 806. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1988BAAS...20..806B. Retrieved on 2008-03-11.

- ↑ Tholen, D. J.; Buie, M. W.; Binzel, R. P.; Frueh, M. L. (1987). "Improved Orbital and Physical Parameters for the Pluto-Charon System". Science 237 (4814): 512–514. doi:. PMID 17730324. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/refs/237/4814/512. Retrieved on 2008-03-11.

- ↑ Bruton, Dan. "Eclipsing binary stars". Midnightkite Solutions. Retrieved on 2007-05-01.

- ↑ Price, Aaron (January 1999). "Variable Star Of The Month: Beta Persei (Algol)". AAVSO. Retrieved on 2007-05-01.

- ↑ Goodricke, John (1785). "Observations of a New Variable Star". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 75: 153–164. doi:. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1785RSPT...75..153G. Retrieved on 2007-05-01.

External links

- A Catalogue of Eclipse Cycles

- Search 5,000 years of eclipses (notice: loads slowly)

- NASA eclipse home page

- International Astronomical Union's Working Group on Solar Eclipses

- Mark's eclipse chasing website

- Interactive eclipse maps site

- Dan McGlaun's Total Eclipse web site

- Why do Hindus believe that the mythological demons Rahu and Ketu cause solar eclipses?

- May 18, 1920 5:22-5:33 eclipse John Paul II

- Google KNOL on Eclipses by Prof. Jay Pasachoff