Orbital eccentricity

In astrodynamics, under standard assumptions, any orbit must be of conic section shape. The eccentricity of this conic section, the orbit's eccentricity, is an important parameter of the orbit that defines its absolute shape. Eccentricity may be interpreted as a measure of how much this shape deviates from a circle.

Under standard assumptions eccentricity ( ) is strictly defined for all circular, elliptic, parabolic and hyperbolic orbits and may take following values:

) is strictly defined for all circular, elliptic, parabolic and hyperbolic orbits and may take following values:

- for circular orbits:

,

, - for elliptic orbits:

,

, - for parabolic trajectories:

,

, - for hyperbolic trajectories:

.

.

Thus  would describe a perfectly circular orbit. For greater values of

would describe a perfectly circular orbit. For greater values of  such that

such that  , the orbit would assume the shape of an increasingly elongated (or flatter) ellipse.

, the orbit would assume the shape of an increasingly elongated (or flatter) ellipse.

For elliptical orbits, a simple proof shows that sin−1 yields the projection angle of a perfect circle to an ellipse of eccentricity

yields the projection angle of a perfect circle to an ellipse of eccentricity  . For example, to view the eccentricity of the planet Mercury (0.2056), one must simply calculate the inverse sine to find the projection angle of 11.86 degrees. Next, tilt any circular object (such as a coffee mug viewed from the top) by that angle and the apparent ellipse projected to your eye will be of that same eccentricity.

. For example, to view the eccentricity of the planet Mercury (0.2056), one must simply calculate the inverse sine to find the projection angle of 11.86 degrees. Next, tilt any circular object (such as a coffee mug viewed from the top) by that angle and the apparent ellipse projected to your eye will be of that same eccentricity.

Contents |

Calculation

Eccentricity of an orbit can be calculated from orbital state vectors as a magnitude of eccentricity vector:

where:

is eccentricity vector.

is eccentricity vector.

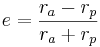

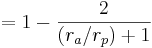

For elliptic orbits it can also be calculated from distance at apoapsis and periapsis:

where:

Examples

The eccentricity of the Earth's orbit is currently about 0.0167. Over thousands of years, the eccentricity of the Earth's orbit varies from nearly 0.0034 to almost 0.058 as a result of gravitational attractions between the planets (see graph [1]).

In other values, Mercury (with an eccentricity of 0.2056) holds the title as the largest value among the planets of the Solar System. Prior to the redefinition of its planetary status, the dwarf planet Pluto held this title with an eccentricity of about 0.248. The Moon also holds a notable value at 0.0549. For the values for all planets in one table, see Table of planets in the solar system.

Most of the solar system's asteroids have eccentricities between 0 and 0.35 with an average value of 0.17. [1] Their comparatively high eccentricities are probably due to the influence of Jupiter and to past collisions.

The eccentricity of comets is most often close to 1. Periodic comets have highly eccentric elliptical orbits, with eccentricities just below 1; Halley's Comet's elliptical orbit, for example, has a value of 0.967. Non-periodic comets follow near-parabolic orbits and thus have eccentricities very close to 1. Examples include Comet Hale-Bopp with a value of 0.995086 and Comet McNaught with a value of 1.000030. As Hale-Bopp's value is less than 1, its orbit is elliptical and so the comet will in fact return (in about 4380AD). Comet McNaught on the other hand has a hyperbolic orbit and so may leave the solar system indefinitely.

Planet Neptune's largest moon Triton has the smallest eccentricity of any known body in the solar system; its orbit is as close to a perfect circle as can be currently measured.

Climatic effect

Orbital mechanics require that the duration of the seasons be proportional to the area of the Earth's orbit swept between the solstices and equinoxes, so when the orbital eccentricity is extreme, the seasons that occur on the far side of the orbit (aphelion) can be substantially longer in duration. Today, northern hemisphere fall and winter occur at closest approach (perihelion), when the earth is moving at its maximum velocity. As a result, in the northern hemisphere, fall and winter are slightly shorter than spring and summer. In 2006, summer was 4.66 days longer than winter and spring is 2.9 days longer than fall. Axial precession slowly changes the place in the Earth's orbit where the solstices and equinoxes occur. Over the next 10,000 years, northern hemisphere winters will become gradually longer and summers will become shorter. Any cooling effect, however, will be counteracted by the fact that the eccentricity of Earth's orbit will be almost halved, reducing the mean orbital radius and raising temperatures in both hemispheres closer to the mid-interglacial peak.

See also

- Eccentricity (mathematics)

- Eccentricity vector

- Equation of time

- Milankovitch cycles

References

Prussing, John E., and Bruce A. Conway. Orbital Mechanicsc. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

External links

- World of Physics: Eccentricity

- The NOAA page on Climate Forcing Data includes (calculated) data from Berger (1978), Berger and Loutre (1991) and Laskar et al. (2004) on Earth orbital variations, including eccentricity, over the last 50 million years and for the coming 20 million years

- The orbital simulations by Varadi, Ghil and Runnegar (2003) provide another, slightly different series for Earth orbital eccentricity, and also a series for orbital inclination

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

is radius at

is radius at  is radius at

is radius at

Longitude of the ascending node

Longitude of the ascending node

Semi-major axis

Semi-major axis Mean anomaly at

Mean anomaly at  True anomaly

True anomaly Semi-minor axis

Semi-minor axis

Eccentric anomaly

Eccentric anomaly Mean longitude

Mean longitude True longitude

True longitude