Dutch people

| The Dutch (Nederlanders) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Dutch people talking on the street |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total population | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

20 million - 30 million |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dutch | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Catholicism, Protestantism , Nontheism.[21][22] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Afrikaners,[nb 4] Frisians[nb 5] |

The Dutch people (Dutch: Nederlanders) are the dominant ethnic group of the Netherlands.[23]

Dutch people, or descendants of Dutch people, are also found in migrant communities world wide,[nb 6] and form a noteworthy part of the population of Canada,[8]Australia,[9] South Africa[24] and the United States.[5]

In the course of history the Dutch grew from a largely rural society to one of the most urbanized in the world, with 50% of the total population already living in cities by 1500 AD. The traditional art and culture of the Dutch encompasses various forms of traditional music, dances, architectural styles and clothing, some of which are globally recognizable. The Dutch also have a strong presence in the international scene of modernist, and post-modern arts.

The dominant religion of the Dutch is Christianity (both Catholic and Protestant), although in modern times the majority is no longer openly religious. Significant percentages of the Dutch are adherents of humanism, agnosticism, atheism or individual spirituality.

Though always being relatively autonomous within the system of European feudalism, it was only in the 17th century that the first independent Dutch state, the Dutch Republic, became fully independent.[nb 7] During the rule of the Republic the first series of large scale Dutch migrations outside of Europe took place.

The Dutch-speaking community in Belgium is sometimes included in the Dutch ethnic or cultural group, due to the common language, and partially shared culture and history.[25][26] Other sources list the Flemish as an ethnic group[27][28][29] with others stating they are a community rather than an ethnic group.[30]

Contents |

Defining Dutch identity

In the Netherlands, as in most Western-European societies, ethnicity in its classic form has been attenuated by historical developments, and ethnic identity becomes salient only in a limited number of situations.[31] Additionally, probably due to the traditionally open character of Dutch society, ideas of nationhood and national pride have never caught on in a strong degree.[32] It should be noted, however, that the (re)definition of Dutch cultural identity has become a subject of public debate in recent years following the increasing influence of the European Union and the influx of non-Western immigrants in the post-World War II period. In this debate 'typically Dutch traditions' have been put to the foreground, ranging from a history of political and religious tolerance to the celebration of the feast of Sinterklaas.[33] In sociological studies and governmental reports, ethnicity is often referred to with the terms autochtoon and allochtoon.[34] These legal concepts refer to place of birth and citizenship rather than cultural background and do not coincide with the more fluid concepts of ethnicity used by cultural anthropologists.

Dutch identity in the sense of self-identification on a nation-wide scale can be said to have taken shape in the latter part of the 19th century. The Dutch Republic had been marked by particularism, and after the Napoleonic era the Netherlands, although politically united, kept a culturally fragmented outlook until well into the third quarter of the 19th century. Although a more supra-regional orientation was present among some of the Protestant bourgeoisie in the cities of Holland, most people felt primarily attached to their own town or region rather than considering themselves 'Netherlanders'.[35] Some time after c. 1860, in the wake of modernization, this traditional outlook started to erode. The ever faster infrastructural, economic, and political integration of the country was followed by a process of cultural homogenization, and already in the 1870s it was noted that traditional clothing had started to disappear from some villages.[36] At the same time, the improving infrastructure enabled the central government to exert a much more direct influence on people's lives than previously possible, and such innovations as compulsory education and military service produced a new identification with, and loyalty to, the Kingdom of the Netherlands at large. The mass media further contributed to the spread of the Dutch standard language and the development of a national culture at the cost of regional dialects and identities, although the past few decennia have also seen a renewed interest in local culture in reaction to this dominant tendency. Eventually many regional traditions have disappeared completely or were greatly transformed,[37] while others, such as the Elfstedentocht, gained the status of a national event.[38]

History

Ethnogenesis

- See also: Germanic peoples

The earliest traces of the ethnogenesis of the Dutch people can seen as far back as the Early Middle Ages. There was a significant increase of Dutch identity in the Late Middle Ages and early modern times (c. 1450-1650).

The Franks, who in the Early Middle Ages conquered and partially colonized the area corresponding to the modern day Netherlands, played a major role in laying down the elements that would later be part of Dutch culture by introducing and consolidating Christianity and imposing the social and administrative structures of the Frankish state.[39] The Franks themselves are mentioned first as a loose federation of tribes that inhabited the region north and east of the Roman limes in the 3rd century, roughly between the Rhine and the Weser, and gradually expanded into northern Gaul as the Western Roman empire collapsed in the course of the 4th and 5th centuries, first as foederati under Roman overlordship, later independently. The origin of the Dutch people itself, which emerged much later, cannot be established as easily in terms of ancient tribal societies. For the early Middle Ages, written sources are sparse and archeological data are difficult to interpret. While most older (19th and early 20th century) historiography speaks of a division between Frisians in the north, Franks in the south and Saxons in the east, more recent research has questioned this traditional view.[40] Especially the archeological evidence, although always hard to interpret, suggests demographic continuity for some parts of the country and depopulation and possible replacement in other parts, notably the coastal areas of Frisia and Holland.[41]

The transition from a largely tribal and rural society to a feudal and urban one was gradual, but greatly accelerated during the late 12th and 13th century. Prior to extensive Roman contact, the Low Countries had been inhabited by rural tribal communities. The new way of living that followed the Frankish conquest ultimately made it possible for a new ethnic group to emerge. The process of Christianization coincided with the loss of traditional Germanic tribalism, in which almost every village had its personal chieftain or even king, and with the continued evolution of the Dutch language.[42]

Batavian Myth

In the wake of a renewed interest in Classical Antiquity, Dutch Humanist writers of the late 15th and early 16th centuries began to speculate about the nature and location of the ancient Batavians, Germanic allies of the Romans who are mentioned by the Roman historian Tacitus and of whom little was known at that time. Writers from both Holland and Guelders laid claim to their region being the historical homeland of the Batavians. When Holland's political significance grew in the course of the 16th century, the issue was gradually decided in favour of the Hollandic side.[43] During the revolt against Spain, the claim of Batavian ancestry was extended to provinces outside Holland (although it never completely shook off its Hollandic connection),[44] and the figure of Julius Civilis, who had led a successful rebellion against the Romans, was represented as an ancient defender of the same liberties the Dutch rebels were fighting for. The 'ancestral' Batavians themselves provided models of righteous defiance combined with wise moderation for the whole nation to follow, and the idea of historical continuity with the Batavians became a national myth that endured in some form well into the 20th century.

High and Late Middle Ages

As Western Europe emerged from the Migration Period, feudal states filled in the power vacuum left by the fall of the Roman Empire. The Low Countries were no exception and feudal society soon took hold of the region. Indeed many of most dominant fiefs have passed on their names to the modern provinces that make up the provinces of the Netherlands and Belgium.[nb 8] Though they shared cultural and linguistical characteristics, the Dutch were effectively politically divided as the many fiefs initially all had different rulers. In subsequent centuries these various liege lords handed out a great number of town privileges, which by the 12th century (considerably earlier than in most of Europe) meant that a great deal of power had transferred from the nobility to the cities. The end of this period saw the rise of Protestantism, the Dutch being among the first to adopt this alternative form of Christianity in large numbers, and the formation of the Burgundian Netherlands which was followed by the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549, which were monumental steps towards Dutch autonomy.[45] Culturally this period also saw the expansion of the Dutch into northern regions at the expense of the Frisians,[45] and the eventual subjection of Frisia itself, while at the same time the Southern Dutch were establishing their cities (Ghent, Antwerp and Bruges) as the powerhouses of Northern Europe. The Regions of the southern Dutch were accumulating vast amounts of wealth; with Antwerp even becoming the second largest European city north of the Alps by 1560.[45] The Dutch language also underwent a major transformation. Early in this period, Old Dutch lost much of its inflection and underwent a number of sound shifts resulting in a new stage known as Middle Dutch (c. 1150-1500).[46]

Independent Dutch state

With the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549, Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, transformed this agglomeration of lands into a unified entity of which the Habsburgs would be the heirs. However, following excessive taxation together with attempts at diminishing the autonomy of the Dutch, followed by the religious oppression after being transferred to Habsburg Spain, the Dutch revolted, in what would become the Eighty Years' War. For the first time in their history, the Dutch established their independence from foreign rule.[45]

The war eventually ended in a stalemate. The Northern Dutch reached de facto independence while the Southern Dutch (whose cultural and economic elite had fled to the North) remained under Spanish rule, resulting in a political division of the Dutch. While the power of the Southern cities was now eroding, the Northern Dutch approached the pinnacle of their wealth: they became a world power and arts and culture flourished. The Northern Dutch were now the avant-garde of Dutch culture. A practical example of this phenomenon, was the rise of painters from the North. Vermeer, Rembrandt, Hals and Steen were now the most famous Dutch painters, replacing their Southern counterparts (such as Bosch, Van Eyck and Bruegel) who had held that position in the previous era.[45]

Dutch maritime power allowed for the establishment of colonies, though the wealth present in their homeland meant that with the exception of South Africa and the New York-area in North America, few regions saw actual settling of Dutch colonists in large numbers.[47]

As the Northern Dutch experienced the Dutch Golden Age, the traditional range of the Dutch moved further up. The Dutch part of modern France (roughly the area of the modern region of Nord-Pas-de-Calais located on the Dutch periphery, and once the center of Dutch Protestantism), collapsed among Spanish, and later French rule, leaving only 20,000 Dutch-speakers today as opposed to an estimated 410,000 in the year 1500.[46] The French language would also increase its range into modern Belgium starting around the beginning of the 18th century. The Dutch language itself was standardized during this period, sparking both an increase in Dutch literature as well as a decrease in dialectal diversity.[48]

Modern Era

Dutch wealth and influence had, by the second half of the 18th century, begun to diminish. The people had been split between Orangists, supporters of the Stadholder (a historical Dutch title, and a rare type of de facto hereditary head of state within the Dutch Republic) and the Patriots. In the minor civil war that ensued, the Patriots lost and in 1787 fled to the Dutch-speaking area of Dunkirk in France; only to return 7 years later together with the French revolutionary army and overthrow the Stadholder, who fled to Britain. The onslaught of the French revolutionary wars and the following Napoleonic wars saw Dutchmen fighting on both sides.[49] The fall of Napoleon and the growing power of Prussia, resulted in the creation of a buffer state between France and the east. The United Kingdom of the Netherlands encompassed all Dutch-speaking areas in continental Europe with the exception of those situated in northern France. The country however wasn't exclusively Dutch, and a revolt started among its French-speaking inhabitants resulted in the establishment of Belgium in 1830. The subsequent oppression of the Dutch language resulted in a movement later known as the Flemish Movement, striving for equality of the Flemish in Belgium.[46]

The Netherlands remained neutral during the First World War, while Belgium was invaded by Germany. Over a million Dutch-speaking Belgians fled to the Netherlands where they received aid, food and shelter. Over 100,000 stayed in the Netherlands the duration of the war, greatly improving the relations between both countries. After the interbellum, the Second World War erupted which resulted in the deaths of over 230,000 Dutchmen.[50] The following baby boom propelled the population. In the Netherlands alone there has been a 51% increase of the totally number of ethnically Dutch inhabitants of the Netherlands since 1940.[nb 9]

Apart from the social and political turmoil as described above, this period was also marked with two occurrences of mass emigration. The first wave left Europe between 1850 and the start of World War I, mainly to the United States and South Africa, but also regions belonging to the Dutch Empire, such as Indonesia. The second emigration wave lasted roughly from 1946 to 1960, and saw large Dutch emigration not only to the United States and South Africa, but also to Australia, New Zealand and Canada.[51]

Genetics

The genetic makeup of the Dutch is typified by a high occurrence of the Y-chromosome markers: haplogroup R1b (averaging 70%) and haplogroup I (averaging 25%). These chromosomes are associated with Eurasiatic Cro Magnoid homo sapiens of the Aurignacian culture, the first modern humans in Europe, and the people of the Gravettian culture that entered Europe from the Middle East 20,000 to 25,000 years ago.[52]

With 70.4%, the Dutch have one of the highest percentages of haplogroup R1b occurrences in Northwestern Europe, comparable to that of the (combined) British population; 72%. Neighbouring populations have lower occurrence of this chromosome (French: 52.2% and Germans: 50.0%); with again a percentage similar to that of the Dutch among the inhabitants of the Iberian peninsula and French Atlantic coast.[53] The Dutch hence fit the Atlantic Haplotype Modal, which is the primary model of peoples living along or in the vicinity of the Atlantic Ocean and the North Sea.[54]

Within the R1b haplogroup its R1b1b2a1 subclade is most dominant, and in fact peaks in occurrence among the Dutch and Frisians at 37.2%. The Dutch share this high rate with the people in Southwest England (21.4%) and Denmark (17.7%).[55] Other haplogroups are less frequent in the Dutch population: Haplogroup E (Hg E3b1a) less than 5% and haplogroup R1a1 (3.7%). The latter is found more frequently in East of the Netherlands.[56]

Ethnic nationalism

As did many European ethnicities during the 19th century,[nb 10] the Dutch also saw the emerging of various Greater Netherlands- and Pan-Movements seeking to unite the Dutch across the continent. During the first half of the 20th century there was a prolific surge in writings concerning the subject. One of its most active proponents was the acclaimed historian Pieter Geyl, who wrote 'De Geschiedenis van de Nederlandsche stam' (Dutch: The History of the Dutch tribe/people) as well as numerous essays on the subject.

During World War II, when both Belgium and the Netherlands fell to German occupation, fascist elements (such as the NSB and Verdinaso) tried to convince the Nazis into combining the Netherlands and Flanders. The Germans however refused to do so, as this would conflict with their ultimate goal of a 'Germanic Europe'.[nb 11] During the entire Nazi occupation the Germans denied any assistance to Dutch ethnic nationalism, and, by decree of Hitler himself, actively opposed it.[57]

Beginning in the 1970s, a renewed interest in ethnicity appeared, which also marked the beginning of cultural and linguistic cooperation between Belgium (Flanders) and the Netherlands which continues to this day. The issue of reuniting regularly emerges, most recently after the long Belgian political crisis of 2007/2008. Aside from individual supporters (Grootneerlandisme) there exist a number of political party's/social movements such as the Dutch Peoples-Union, Die Roepstem, Voorpost. Most of these organizations, however, (especially the Dutch Peoples-Union) belong to the extreme right of Dutch and Belgian politics.

Differences among the Dutch and the Flemings

There is cultural division between the Dutch and the Flemings. Although the actual differences are often exaggerated,[58] they are worthy of mention. Internal divergences play a part in the daily life within the Dutch-speaking region and are factors in personal identification among its inhabitants. Besides the general urban-rural contrasts, differences are most notable between the Northern Dutch (roughly those Dutch living North of the rivers Rhine and/or Meuse), and the Southern Dutch (those living South of these rivers). The division is partially caused by (traditional) religious differences, with the North predominantly Protestant and the South having a majority of Catholics. Linguistic (dialectal) differences and to a lesser extent, historical economic development of both regions are also important elements in any dissimilarity.

Various factors contributing to differences within the Dutch are:

- The Rhine-Meuse Delta. This delta traditionally formed a barrier within the Low Countries. Around 120 A.D. it formed the Northernmost Roman border in Continental Europe. During the second half of the Dutch Revolt it became the boundary of the contested areas, with the Dutch republic in firm command of the Northern Netherlands and the Spanish in command of Flanders and Southern Brabant, the regions now known as the provinces of North-Brabant and Limburg were contested. The Dutch Republic controlled vital fortified cities, while the Spanish generally controlled the surrounding countryside.

- Religious development. Protestantism is part of the cultural division between the Dutch and the Flemish. During the Dutch revolt the Spanish controlled the South, whose Protestants fled North; while the Republic controlled the North, with many Catholics moving south. The North became largely Protestant; while the South, under the influence of the Counter reformation, remained or reverted to Catholicism.

- Political development. The Dutch Revolt did not accomplish it intended goals; the liberation of all members of the Union of Utrecht. Brabant was only partially in rebel hands, while Mechelen and the county of Flanders remained under Spanish control. The Northern Netherlands would have a relatively constant political climate for centuries, while the situation in the South would remain instable, and would be part of the Southern Netherlands, Austrian Netherlands and the United States of Belgium. After the defeat of Napoleon, the Low Countries were briefly unified in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. This Kingdom collapsed due to various causes. The Flemings would become part of the bi-lingual state of Belgium. Nowadays, Belgium is a largely segregated state, where the speakers of the two main languages, Dutch and French, live in separate communities.

- Dialectal situation. Though all Dutch dialects form a continuum, general consensus among linguists is that the Dutch language has 28 main dialects. These dialects are usually grouped into 6 main categories; Hollandic, West-Flemish/Zealandic, East Flemish, Brabantic, Limburgish and Dutch Saxon.[59] Of these dialects, Brabantic, Limburgish and East Flemish are spoken exclusively by the Southern Dutch, whereas Hollandic and Dutch Saxon are solely spoken by Northerners. West-Flemish/Zealandic is a cross border dialect in this respect.

- Economic development. Prior to the Dutch revolt the South was the economic powerhouse of the Low Countries, while the North at this time was comparatively rustic and less urbanized. This changed when during the revolt when the Southern economy was destabilised by the revolt, leading to a braindrain to the North, which soon became more wealthy and powerful.

Northern Dutch

Northern Dutch culture is marked by Protestantism. Though today many do not adhere to Protestantism anymore, or are only nominally part of a congregation, Protestant (influenced) values and custom are present. Generally, it can be said the Northern Dutch are more pragmatic, favor a direct approach and display a less exuberant lifestyle when compared to Southerners.[60] On a global scale, the Northern Dutch have formed the dominant vanguard of the Dutch language and culture since the fall of Antwerp, exemplified by the use of 'Dutch' itself as the demonym for the country in which they form a majority; the Netherlands. Linguistically, Northerners speak any of the Hollandic, Zealandic and Dutch Low Saxon dialects natively, or are influenced by them when they speak the Standard form of Dutch. Economically and culturally the traditional center of the region have been the provinces of North and South Holland, or today; the Randstad, although for a brief period during the 1200s/1300s it lay in east, when various eastern towns and cities aligned themselves with the emerging Hanseatic League. The entire Northern Dutch cultural area is located in the Netherlands, its ethnically Dutch population is estimated to be just under 10,000,000.[nb 12]

Southern Dutch

The Southern Dutch sphere generally consists of the areas in which the population was traditionally Catholic. During the early Middle Ages up until the Dutch Revolt, the Southern regions were more powerful, as well as more culturally and economically developed.[60] At the end of the Dutch Revolt, it became clear the Habsburgs were unable to reconquer the North, while the North's military was too weak to conquer the South, which, under the influence of the Counter-Reformation, had started to develop a political and cultural identity of its own.[61] The Southern Dutch, including Dutch Brabant and Limburg, remained Catholic or returned to Catholicism. The Dutch dialects spoken by this group are Brabantic, Limburgish and East and West Flemish. Unlike the Northern Dutch, Southerners are spread out between three countries; Belgium (where they are known as Flemings), the Netherlands and a small (~20,000) minority living in France. In the Netherlands, an oft-used adage used for indicating this cultural boundary is the phrase boven/onder de rivieren (Dutch: above/below the rivers), in which 'the rivers' refer to the river Rhine and Meuse. The total population of the Southern Dutch cultural sphere is estimated to be at 9,500,000.[nb 13]

Flemings

Today Flemings has become the term used for all Dutch speaking communities in the Southern Netherlands, now Belgium, as well as anyone belonging to the modern part of Belgium named the Flemish Community and/or an inhabitant of the Flemish Region of Belgium.[62] Historically however, Fleming had a much broader meaning, encompassing all Dutch, whether northern or southern. In fact, 'Flanders' was often used as a synonym for 'Low Countries', as seen in the title of a Spanish contemporary play (and referring to) the Dutch Revolt called Los amotinados de Flandes, meaning 'the rioters of Flanders'.[63]

With the revolt of 1830 resulting in the creation of the country, Belgium, there now existed a strained interplay between the two countries. In the Netherlands the revolt was a traumatic experience and resulted in a reticent and contentious relationship with the newly formed Belgium and a largely indifferent attitude towards its Dutch-speaking inhabitants.[64] In Belgium the bliss of the revolt soon shifted as the Dutch language and culture were oppressed by the new Francophone government. The following social struggle between Dutch-speakers of Belgium, or Flemings as they began calling themselves (reminiscent of the Dutch County of Flanders, a rich and powerful medieval fief) and French-speakers would eventually transform Belgium from a unitary to a federal state. This internal Belgian strife would further result in the Flemings calling for a separate Flemish nation, culminating in a clear social and political divide between the modern Dutch and the Flemings.

Historically, culturally and linguistically the situation is complex. Until 1980, for example, the current Flemish Community was known as the Dutch Cultural Community and Vlaams Belang, a right-wing Flemish nationalist party making up ~25% of the Flemish Parliament, writes in its program that one of its goals is the protection of Dutch culture and language.[65] Since the end of World War II and the establishment of the European Union, there has been a growing interest in the preservation of what is often called 'Dutchophone Culture' among the various governments of Flanders/Belgium and the Netherlands.[66] Resulting in various "Cultural treaties", an international Dutch-language broadcasting channel (BVN) and linguistic cooperation (Taalunie) among others.

Related ethno-linguistic groups

Frisians

Frisians, specifically West Frisians, are an ethnic group; present in the North of the Netherlands; mainly concentrating in the Province of Friesland. Culturally, modern Frisians and the (Northern) Dutch are rather similar; the main and generally most important difference being that Frisians speak West Frisian, one of the three subbranches of the Frisian language.

Historically the area that was known as 'Frisia', was much larger than it is now. At its peak around the 720s it stretched from Western Flanders to southern Denmark. It should be noted that a clear Frisian identity did not exist at this time, as during the 8th century, both the people inhabiting the region as well as most of the Germanic dialects they spoke (Old Saxon, Old Dutch and Old Frisian) were still quite similar to each other.[67] After a long period of strife Charlemagne defeated the Frisians and consolidated the Frisian lands into the Frankish Empire. Soon after his death, these territories fell apart again, and, during the Middle Ages, the Frisian territories were autonomous, under the leadership of frequently changing tribal chiefs. After a series of wars with the Dutch, specifically the Counts of Holland, starting in 1272 and ending in 1524, Frisia lost its independence, became part of the Seventeen Provinces in 1579, joined the Dutch revolt against Spain in 1568, and have remained a part of the Netherlands ever since.[68]

Today there exists a tripartite of the original Frisians; namely the North Frisians, East Frisians and West Frisian, caused by the Frisia's constant loss of territory in the Middle Ages,[69] but the West Frisians in the general do not feel or see themselves as part of a larger group of Frisians, and, according to a 1970 inquiry, identify themselves more with the Dutch than with East or North Frisians.[70]

Because of centuries of cohabitation and active participation in Dutch society, as well as being bilingual, the Frisians are not treated as a separate group in Dutch official statistics.

Afrikaners

- Main articles: Afrikaners and Afrikaans.

The Afrikaners are a relatively young South African and Namibian ethnic group. They are largely the descendants of Dutch emigrants augmented by smaller numbers of Rhinelandic Germans and French Huguenots, who settled around the Western Cape of South Africa around the 17th century. Initially they were divided among the Cape Dutch, and the Trekboers, before later becoming collectively known as Afrikaners.

Their main language is Afrikaans, a form of creolized Dutch, which was considered a Dutch dialect until the late 19th century. Afrikaans and Dutch are mutually intelligible, though this relation can in some fields (such as lexicon, spelling and grammar) be asymmetric, as it is easier for Dutch-speakers to understand Afrikaans than it is for Afrikaans-speakers to understand Dutch.[71]

Many Afrikaners acknowledge that they descend, though not exclusively, from the Dutch,[24] but, largely due to Afrikaner nationalism following the oppression of the Cape Dutch and Boers by the British Empire, which somewhat estranged the South African Dutch from their European counterparts, consider themselves to be Afrikaners, instead of Dutch.

Basters

The Basters are the descendants of Cape Dutch and indigenous South African women. They largely live in Namibia and are similar to Coloured or Griqua people in South Africa. The name Baster is derived from the Dutch word for ‘bastard’ (or ‘crossbreed'). While some people consider this term pejorative, the Basters proudly use the term as an indication of their history in the same way as the Métis or "New People" of Canada.

Dutch Eurasians

Dutch Eurasians, generally known as Indische Nederlanders (Indian/Indonesian Dutch) or by their nickname Indos in Dutch, are the descendants of Dutchmen and Indonesian women, often Javanese or Moluccan.

Burghers

The Burghers are Eurasians, historically from Sri Lanka, consisting for the most part of male-line descendants of European colonists from the 16th to 20th centuries (mostly Portuguese, Dutch and British) and local Sinhalese women.

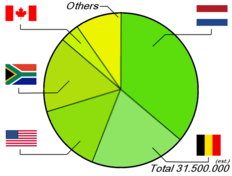

Statistics

The total number of Dutch can be defined in roughly two ways. By taking the total of all people with full Dutch ancestry, resulting in an estimated 16.000.000 Dutch people,[72] or by the sum of all people with both full and partial Dutch or Flemish ancestry, which would result in a number around 31.500.000.

Dutch per country, world wide (including all Flemings).

|

Excluding the Netherlands and Belgium.

|

Dutch language speakers in Europe.

|

Linguistics

Language

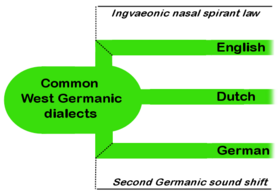

Dutch is the language spoken by most Dutch people. It is a West Germanic language spoken by around 22 million people. The language was first attested in 470 AD,[nb 14] in a Frankish legal text, the Lex Salica, and has a written record of more than 1550 years.

As a West Germanic language, Dutch is related to other languages in that group such as Frisian, English and German. Many West Germanic dialects experienced a series of sound shifts. The Anglo-Frisian nasal spirant law and Anglo-Frisian brightening resulted in certain early Germanic languages evolving into what are now English and Frisian, while the Second Germanic sound shift resulted in what would become German. Dutch experienced none of these sound changes and can thus be said to occupy a central position within the West Germanic languages.

Standard Dutch has a sound inventory of 13 vowels, 6 diphthongs and 23 consonants, of which the voiceless velar fricative (hard ch) is considered a well known sound, perceived as typical for the language. Other relatively well known features of the Dutch language and use are the frequent use digraphs like Oo, Ee, Uu and Aa, the ability to form long compounds and the use of diseases as profanity (in the Netherlands only).

Dutch immigrants also exported the Dutch language. Dutch was spoken in United States as a native language from the arrival of the first permanent Dutch settlers in 1615, surviving in isolated ethnic pockets until ~1900, when it ceased to be spoken with the exception of 1st generation Dutch immigrants. The Dutch language nevertheless had a significant impact on the region around New York. For example, American president Martin van Buren first language was Dutch.[73] Most of the Dutch immigrants of the 20th century quickly began to speak the language of their new country. For example, of the inhabitants of New Zealand, 0.7% say their home language is Dutch,[nb 15] despite the percentage of Dutch heritage being considerably higher.[74]

Dutch is currently an official language of the Netherlands, Belgium, Suriname, Aruba, the Netherlands Antilles and the European Union. In South Africa, Afrikaans is spoken, a descendant of Dutch, which itself was an official language of South Africa until 1925. The Dutch, Flemish and Surinamese governments coordinate their language activities in the Nederlandse Taalunie (Dutch Language Union), an institution also responsible for governing the Dutch Standard language, for example in matters of orthography.

Etymology of autonym and exonym

- Further information: Dietsch

The origins of the word Dutch go back to Proto-Germanic, the ancestor of all Germanic languages, *theudo (meaning "national/popular"); akin to Old Dutch dietsc, Old High German diutsch, Old English þeodisc and Gothic þiuda all meaning "(of) the common (Germanic) people". As the tribes among the Germanic peoples began to differentiate its meaning began to change. The Anglo-Saxons of England for example gradually stopped referring to themselves as þeodisc and instead started to use Englisc, after their tribe. On the continent *theudo evolved into two meanings: Diets (meaning "Dutch (people)" (archaic)[nb 16]) and Deutsch (German, meaning "German (people)"). At first the English language used (the contemporary form of) Dutch to refer to any or all of the Germanic speakers on the European mainland (e.g. the Dutch, the Flemings and the Germans). Gradually its meaning shifted to the Germanic people they had most contact with, both because their geographical proximity, but also because of the rivaltry in trade and overseas territories: the people from the Republic of the Netherlands, the Dutch.[75]

In the Dutch language, the Dutch refer to themselves as Nederlanders. Nederlanders derives from the Dutch word "Neder", a cognate of English "Nether" both meaning "low", and "near the sea" (same meaning in both English and Dutch), a reference to the geographical texture of the Dutch homeland; the western portion of the Northern European plain.[76][77][78] Although not as old as Diets, the term Nederlands has been in continuous use since 1250.[79]

Names

Dutch surnames (and surnames of Dutch origin) are generally easily recognizable. There are several main types of surnames in Dutch:

- Patronymic surnames; the name is based on the personal name of the father of the bearer. Historically this has been by far the most dominant form. These type of names fluctuated in form as the surname was not constant. If a man called Willem Janssen (William, John's son) had a son named Jacob, he would be known as Jacob Willemsen (Jacob, Williams' son). Following civil registry, the contemporary form became permanent. Hence today many Dutch people are named after ancestors living in the early 1800s when civil registry was introduced to the Low Countries. These names rarely feature tussenvoegsels.

- Surnames relating to geographical origin; the name is based on the location on which the bearer lives or lived. In Dutch this form of surname nearly always includes one or several tussenvoegsels, mainly van, van de and variants. Many immigrants removed the spacing, leading to deived names for well known people like Cornelius Vanderbilt.[80] While "van" denotes "of", Dutch surnames are sometimes associated with the upper class of society or aristocracy (cf. William of Orange). However, in Dutch van often reflects the original place of origin (Van Der Bilt - He who comes from Bilt); rather than denote any aristocratic status.[81]

- Surnames relating to Occupation; the name is based on the occupation of the bearer. Well known examples include Molenaar, Visser and Smit. This practice is similar to English surnames (the example names translate perfectly to Miller, Fisher and Smith).[nb 17]

- Surnames relating to physical appearance/other features; the name is based on the appearance or character of the bearer (at least at the time of registration). For example "De Lange" (the tall one), "De Groot" (the big one), ["De Dappere" (the brave one).

- Other surnames may relate to animals. For example; De Leeuw (The Lion), Vogels (Birds), Koekkoek (Cuckoo) and Devalck (The Falcon); to a desired social status; e.g., Prins (Prince), Keuning/De Koninck (King), De Keyzer (Emperor). There is also a set of made up or descriptive names; e.g. Naaktgeboren (born naked).

Dutch names can differ greatly in spelling. The surname Baks, for example is also recorded as Backs, Bacxs, Bakx, Baxs, Bacx Backx, Bakxs and Baxcs. Though written differently, pronunciation remains identical. Surnames of Dutch migrants in foreign environments (mainly the Anglosphere and Francophonie) are often adapted, not only in pronunciation but also in spelling.

Culture

- Further information: Dutch architecture, Dutch customs and etiquette, Dutch cuisine, Dutch festivities, Dutch literature, Dutch music, Dutch art, and Dutch folklore

Religion

- Further information: Religion in the Netherlands

Prior to the arrival of Christianity, the ancestors of the Dutch adhered a form of Germanic paganism augmented with various Celtic elements. At the start of the 6th century the first (Hiberno-Scottish) missionaries arrived. They were later replaced by Anglo-Saxon missionaries, who eventually succeeded in converting most of the inhabitants by the 8th century.[82] Christianity then dominated Dutch religion until the early 16th century, when the Protestant Reformation began to form. Among the Dutch it began its spread in the Westhoek and the County of Flanders, where secret sermons were held in the outside, called hagenpreken ("hedgerow orations") in Dutch. The ruler of the Dutch regions, Philip II of Spain, felt it was his duty to fight Protestantism, and, after the wave of iconoclasm, sent troops to crush the rebellion and make the Low Countries a Catholic region once more.[83] The Protestants, in the Southern Low Countries fled North en masse.[83] Most of the Dutch Protestants were now concentrated in the free Dutch provinces above the river Rhine, while the Catholic Dutch were situated in the Spanish occupied or dominated South. After the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, Protestantism did not spread South, resulting in a religious situation, lasting to this day.

Contemporary Dutch are generally nominally Christians.[84][85] People of Dutch ancestry in the United States are generally more religious than their European counterparts; for example the numerous Dutch communities of western Michigan remain strongholds of the Reformed Church in America, and the Christian Reformed Church, both descendants of the Dutch Reformed Church.

Dutch diaspora

Since World War II, Dutch Emigrants mainly went to the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, (until the 1970s) to South Africa. Today Dutch immigrants can be found in most developed countries. In several former Dutch colonies and trading settlements, there are isolated ethnic groups of full or partial Dutch ancestry.

Eastern Europe

During the Ostsiedlung, Germans and Dutch settled east of the Elbe and Saale rivers, regions largely inhabited by Polabian Slavs.[86] After the capture of territory along the Elbe and Havel Rivers in the 1160s, Dutch settlers from flooded regions in Holland used their expertise to build dikes in Brandenburg.[87] From the 13th to the 15th centuries, Prussia invited several waves of Dutch along with Flemings and Frisians to settle throughout the country (mainly along the Baltic Sea coast)[88]

In the early-to-mid 1500s, Mennonites began to move from the Low Countries (especially Friesland) and Flanders to the Vistula delta region in Royal Prussia, seeking religious freedom and exemption from military service. When the Prussian government eliminated exemption from military service on religious grounds, the Mennonites emigrated to Russia. They were offered land along the Volga River. Some settlers left for Siberia in search for fertile land.[89]

Southern Africa

In South Africa, the Dutch settled the Cape in 1652. Initially the settlement was meant as a re-supply point and way station for Dutch East India Company vessels on their way back and forth between the Netherlands and the East Indies. The support station gradually became a settler community. However, the rural inhabitants of the colony soon began to dislike the power held by the Dutch India Company (it stopped the colony's policy of open immigration, monopolized trade, combined the administrative, legislative and judicial powers into one body, told the farmers what crops to grow, demanded a large percentage of every farmer's harvest, and harassed them.) Slowly these farmers moved away from the Cape, eventually becoming known as 'trekboers', and settled deeper into South Africa and eventually Namibia. Today the Boers and Cape Dutch are known collectively as the Afrikaners, while the descendants of Cape Dutch and local black women are known as the Basters.

Southeast Asia

Since the 16th century, there has been a Dutch presence in South East Asia, Taiwan and Japan. In many cases the Dutch were the first Europeans the natives would encounter. Between 1602 and 1796, the VOC sent almost a million Europeans to work in the Asia.[90] The majority died of disease or made their way back to Europe, but some of them made the Indies their new home.[91] Interaction between the Dutch and native population mainly took place in Sri Lanka and the modern Indonesian Islands. Most of the time Dutch soldiers intermarried with local women and settled down in the colonies. Through the centuries there developed a relatively large Dutch-speaking population of mixed Dutch and Indonesian descent, known as Indos or Dutch-Indonesians. The expulsion of Dutchmen following the Indonesian Revolt, means that currently the majority of this group lives in the Netherlands.

Australia and New Zealand

-

- Main articles: Dutch New Zealanders, Australians of Dutch descent

Perhaps the most successful integration of Dutch people took place in Australia and New Zealand. After World War II, thousands of Dutch people emigrated to Australia, peaking in the late 1950s and early 1960s. There are 24 Dutch language programs around Australia and weekly and monthly Dutch news papers plus many social, community and religious clubs. Despite these figures, in both Australia and New Zealand Dutch people are highly integrated. Apart from the typical Dutch surnames many descendants bear, they are largely indistinguishable from the largest ethnic groups, the Anglo-Celtic Australians (85%[92] ) in Australia and other New Zealand Europeans in New Zealand. One major exception exists though. and this concerns senior citizens of Dutch decent, many of whom (because of old age or dementia) have lost the ability to speak English and fall back on their mother tongue; Dutch. A major social problem as they largely lack a way to communicate. Their children generally do not speak Dutch natively or sufficiently.

North America

The Dutch had settled in America long before the establishment of the United States of America.[nb 18] For a long time the Dutch lived in Dutch colonies, owned and regulated by the Dutch Republic, which later became part of the Thirteen Colonies. Nevertheless, many Dutch communities remained virtually isolated towards the rest of America up until the American Civil War, in which the Dutch fought for the North and adopted many American ways.[93]

Most future waves of Dutch immigrants were quickly assimilated. There have been three American presidents of Dutch descent: Martin van Buren (8th, first president who was not of British descent, first language was Dutch), Franklin D. Roosevelt (32nd, elected to four terms in office, he served from 1933 to 1945, the only U.S. president to have served more than two terms) and Theodore Roosevelt (26th).

In Canada 923,310 Canadians claim full or partial Dutch ancestry. The first Dutch people to come to Canada were Dutch Americans among the United Empire Loyalists. The largest wave was in the late 19th and early 20th century, when large numbers of Dutch helped settle the Canadian west. During this period significant numbers also settled in major cities like Toronto. While interrupted by World War I, this migration returned in the 1920s, but again halted during the Great Depression and World War II. After the war a large number of Dutch immigrants moved to Canada, including a number of war brides of the Canadian soldiers who liberated the Low Countries.

See also

- Demographics of the Netherlands

- Dutch Brazil

- Dutch customs and etiquette

- Dutch diaspora

- List of Dutch people

- Netherlands (terminology)

- New Netherlands now called New York.

Notes

- ↑ According to a 1990 study by Statistics Netherlands there were 472,600 Dutch Indonesians residing in the Netherlands. They are the descendants of both Dutchmen and native peoples of Indonesia.

- ↑ Number of people with the Dutch nationality in Belgium

- ↑ Number of inhabitants of Flanders regardless of ancestry

- ↑ Mainly the descendants of Dutch colonists in South Africa, speak Afrikaans a Dutch semi-creol.

- ↑ (Inhabitants of Friesland) Are bilingually Dutch, have a largely intertwined history and also possessing Germanic heritage.

- ↑ See the Dutch diaspora section.

- ↑ The actual independence was accepted by in the 1648 treaty of Munster, in practice the Dutch Republic had been independent since the last decade of the 16th century)

- ↑ For example; Brabant, Holland, Flanders and Guelders.

- ↑ 1940 population compared to modern ethnically Dutch population. (The Netherlands in the 1940s were virtually mono-ethnic)

- ↑ cf. Pan-Germanism, Pan-Slavism and many other Greater state movements of the day.

- ↑ Which would have included all speakers of Germanic language (thus also Danes, Norwegians, Swedes, etc.) as one single nation.

- ↑ Estimate based on the population of the Netherlands, without the Southern Provinces and non-Ethnic Dutch.

- ↑ Estimate based on the Southern Provinces of the Netherlands and Flanders, without non-Ethnic Dutch.

- ↑ "Maltho thi afrio lito" is the oldest attested (Old) Dutch sentence, found in the Salic Law, a legal text written around 450 AD.

- ↑ See article on New Zealand

- ↑ Until World War II, Nederlander was used synonym with Diets. However the similarity to Deutsch resulted in its disuse when the German occupiers and Dutch fascists extensively used that name to stress the Dutch as an ancient Germanic people.

- ↑ Most common names of occupational origin in the 1947 census.

- ↑ The U.S. declared its independence in 1776; the first Dutch settlement was built in 1614: Fort Nassau, where presently Albany, New York is positioned.

References

- ↑ Autochtone population at 1 January 2006, Central Statistics Bureau, Integratiekaart 2006, (external link)

- ↑ Official figures for the number of people with the Dutch nationality living in Belgium in 2007 (excluding Belgians of Dutch ancestry)

- ↑ Official figures for the number of inhabitants of Flanders on 1 January 2008

- ↑ Dutch-born 2001, Figure 3 in DEMOS, 21, 4. Nederlanders over de grens, Han Nicholaas, Arno Sprangers. [1]

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 According to Factfinder.census.gov

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Dutch-born, 2001, Figure 3 in DEMOS, 21, 4. Nederlanders over de grens, Han Nicholaas, Arno Sprangers. [2]

- ↑ 210,000 emigrants since World War II, after return migration there were 120,000 Netherlands-born residents in Canada in 2001. DEMOS, 21, 4. Nederlanders over de grens, Han Nicholaas, Arno Sprangers. [3]

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Based on Statistics Canada, Canada 2001 Census.Link to Canadian statistics.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 2001 Australian statistics

- ↑ Joshuaproject.net gives 164,000 Dutch people living in Germany..

- ↑ Place of birth data collated by OECD based on 2001 UK Census

- ↑ Infoplease.com.

- ↑ Te Ara, the encyclopedia of New Zealand, claims that: "[...] as many as 100,000 New Zealanders are estimated to have Dutch blood in their veins".

- ↑ Joshuaproject.net gives 83,000 Dutch people living in France.

- ↑ See Demographics of Sri Lanka or this link on the Burgher people.

- ↑ Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, Bundesamt für Migration. Ständige ausländische Wohnbevölkerung nach Staatsangehörigkeit, 12/2006. [4]

- ↑ (Dutch) Dutch-born, 2001, Figure 3 in DEMOS, 21, 4. Nederlanders over de grens, Han Nicholaas, Arno Sprangers. [5]

- ↑ gives 26,000 Dutch people living in Denmark..

- ↑ gives 20,000 Dutch people living in Spain..

- ↑ 2006 Irish Census [6]

- ↑ (Dutch) CBS statline Church membership

- ↑ (Dutch)Religion in the Netherlands.

- ↑ (Dutch) 13,186,600, autochthonous population at 1 January 2006, Central Statistics Bureau, Integratiekaart 2006, (external link)

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Based on figures given by Professor JA Heese in his book Die Herkoms van die Afrikaner (The Origins of Afrikaners), who claims the modern Afrikaners (who total around 4.5 million) have 35% Dutch heritage. How 'Pure' was the Average Afrikaner?

- ↑ Ethnic Groups and the State, by Paul R. Brass, ISBN 0389205281, uses Dutch/French with ethnic and Flemish/Walloon for regional/national identities.

- ↑ The European Culture Area, By Terry G. Jordan-Bychkov, Bella Bychkova Jordan, page 210; "The Dutch, also called Flemings, and Walloons aquired a deep-seated mutual antagonism."

- ↑ Thernstrom, Stephan; Orlov, Ann and Handlin, Oscar (1980). Harvard Encyclopedia of American ethnic groups. Harvard University Press. pp. 179. ISBN 9780674375123. http://books.google.com/books?id=npQ6Hd3G4kgC&pg=PA181&dq=flemings+ethnic&lr=&ei=sSkcSeSPBYmesgOdjqSQCQ#PPA179,M1. Retrieved on 2008-11-13.

- ↑ Wright, Sue; Kelly, Helen (1995). Languages in Contact and Conflict. Multilingual Matters. pp. 51. ISBN 9781853592782. http://books.google.com/books?id=BNnm-Bog4awC&pg=PA51&dq=flemings+ethnic&ei=9SccSZfeJo32sgO2i8jNBw#PPA51,M1. Retrieved on 2008-11-13.

- ↑ Eurobalkans: Eurovalkania, University of Michigan 1996, page 35; "Under the Constitution. the government must have an equal number of ministers from the Dutch-speaking and French-speaking ethnic groups (the Flemings and Walloons)".

- ↑ Levinson, David (1998). Ethnic Groups Worldwide. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 14. ISBN 9781573560191. http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=uwi-rv3VV6cC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=dutch+ethnically+flanders&ots=AFH060LBQ5&sig=-D3RoR1n1ZHC04BBacIEYQp0NbU#PPA13,M1. Retrieved on 2008-11-07.

- ↑ M.O. Heisler, "Ethnicity and Ethnic Relations in the Modern West", in J.V. Montville (ed.), Conflict and Peacemaking in Multiethnic Societies (New York 1991), 21-52.

- ↑ W. Shetter, The Netherlands in Perspective. The Dutch Way of Organizing a Society and its Setting. Second, thoroughly revised edition (Utrecht 2002), 208; H. Knippenberg & B. de Pater, De eenwording van Nederland (Nijmegen 2002), 213.

- ↑ Shetter (2002), 201

- ↑ J. Knipscheer and R. Kleber, Psychologie en de multiculturele samenleving (Amsterdam 2005), 76 ff.

- ↑ Knippenberg & De Pater (2002), 37-38.

- ↑ Knippenberg & De Pater (2002), 9, with a reference to Henry Havard visiting the countryside of Friesland and Groningen.

- ↑ As an example, Knippenberg & De Pater mention the traditional fair of Winterswijk, which was abolished in 1875 by the local elite and then revived in 1888 as a much more sober festival dedicated to the Royal House and celebrated on the Crown Princess' birthday from then on. (p. 178)

- ↑ Knippenberg & De Pater (2002), 206.

- ↑ D. P. Blok, De Franken in Nederland (Bussum 1974), 7, 60 ff.

- ↑ Cf. Blok (1974), 36-37 and J. van Eijnatten, F. van Lieburg, Nederlandse religiegeschiedenis (Hilversum 2006), 42-43, on the uncertain identity of the 'Frisians' in early Frankish sources; Blok (1974), 54-55 on the problems concerning 'Saxons' as a tribal name; Th. de Nijs, E. Beukers and J. Bazelmans, Geschiedenis van Holland (Hilversum 2003), 31-33 on the fluctuating character of tribal and ethnic distinctions for the early Medieval period.

- ↑ Blok (1974), 117 ff.; De Nijs et al. (2003), 30-33

- ↑ (Dutch) The linguistic magazine Onze taal on the oldest and earliest Dutch.

- ↑ I. Schöffer, "The Batavian Myth during the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries". J.S. Bromley and E.H. Kossmann (eds.), Britain and the Netherlands, vol. V: Some political Mythologies. Papers delivered to the fifth Anglo-Dutch Historical Conference (The Hague 1975), 78-101, esp. 89-90

- ↑ Schöffer (1975), 90

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 45.4 Chapter 3, forming political unity, paragraph 3; The Age of Habsburg (1477-1588).

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 (Dutch)Geschiedenis van het Nederlands by M. Van der Wal. Middelnederlands.

- ↑ Geheugen van Nederland, (link) on Dutch emigration and motives.

- ↑ (Dutch)Taal als mensenwerk. N. Van der Sijs. On the emerging of Standard Dutch and Dutch RP

- ↑ For example, Dutch fought among the French Imperial Guard in Russia (link) and by comparison, the Dutch were the largest non-British force (17,000) under Wellington at Waterloo. (Barbero, pp. 75–76)

- ↑ Gregory, Frumkin. Population Changes in Europe Since 1939, Geneva 1951.

- ↑ Nederlanders over de grens, H. Nicholaas

- ↑ The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in Extant Europeans: A Y Chromosome Perspective - Ornella Semino et al.[7]

- ↑ http://www.healthanddna.com/Ysample.PDF

- ↑ Haplogroup R1b (Atlantic Modal Haplotype)

- ↑ [8] Y-chromosome Short Tandem Repeat DYS458.2 Non-consensus Alleles Occur Independently in Both Binary Haplogroups J1-M267 and R1b3-M405, The Croatian Medical Journal, Vol. 48, No. 4. (August 2007), pp. 450-459

- ↑ European R1a1 measurements(referred to as M17 or Eu19) in Science vol 290, 10 November 2000 [9]

- ↑ For example explicit orders not to create of a voluntary Dutch Waffen SS division comprising of soldiers from the Netherlands and Flanders. (Link to documents)

- ↑ Nederlandse en Vlaamse identiteit, Betekenis, onderlinge relatie en perspectief. Civis Mundi, 2006.

- ↑ Taaluniversum website on the Dutch dialects and main groupings.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Voor wie Nederland en Vlaanderen wil leren kennen. By J. Wilmots

- ↑ Cf. Geoffrey Parker, The Dutch Revolt: "Gradually a consistent attitude emerged, a sort of 'collective identity' which was distinct and able to resist the inroads, intellectual as well as military, of both the Northern Dutch (especially during the crisis of 1632) and the French. This embryonic 'national identity' was an impressive monument to the government of the archdukes, and it survived almost forty years of grueling warfare (1621-59) and the invasions of Louis XIV until, in 1700, the Spanish Habsburgs died out." (Penguin edition 1985, p. 260). See also J. Israel, The Dutch Republic, 1477-1806, 461-463 (Dutch language version).

- ↑ Van Dale Dutch dictionary, entry; 'Vlaming'.

- ↑ De Tachtigejarige Oorlog in Spaanse ogen, by Y. Rodríguez Pérez (page 186). ISBN 9077503 19 6

- ↑ Geschiedenis van de Nederlanden, by J.C.H Blom and E. Lamberts, ISBN 9 789055 744756; page 383.

- ↑ Offical party material; see page 22 or search 'Nederlandse cultuur'.

- ↑ Geschiedenis van de Nederlanden, by J.C.H Blom and E. Lamberts, ISBN 9 789055 744756; page 384/385.

- ↑ On the history of the Frisian language.

- ↑ Frisian History

- ↑ Frisian history. (English)

- ↑ Frisia. 'Facts and fiction' (1970), by D. Tamminga.

- ↑ Oxford Journal on Mutual Comprehensibility of Written Afrikaans and Dutch

- ↑ In the 1950s (the peak of traditional emigration) about 350,000 people left the Netherlands, mainly to Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States and South Africa. About one-fifth returned. The maximum Dutch-born emigrant stock for the 1950s is about 300,000 (some have died since). The maximum emigrant stock (Dutch-born) for the period after 1960 is 1.6 million. Discounting pre-1950 emigrants (who would be about 85 or older), at most around 2 million people born in the Netherlands are now living outside the country. Combined with the 13,1 million ethnically Dutch inhabitants of the Netherlands, there are about 16 million people who are Dutch, in a minimally accepted sense. Autochtone population at 1 January 2006, Central Statistics Bureau, Integratiekaart 2006', ((Dutch) external link)

- ↑ No, America's never been a multicultural society

- ↑ As many as 100,000 New Zealanders are estimated to have Dutch blood in their veins (some 2.1% of the current population of New Zealand).

- ↑ www.etymonline.com and (Dutch) Etymologisch Woordenboek van het Nederlands entries "Dutch" and "Diets".

- ↑ (Dutch) See J. Verdam, Middelnederlandsch handwoordenboek (The Hague 1932 (reprinted 1994)): "Nederlant, znw. o. I) Laag of aan zee gelegen land. 2) het land aan den Nederrijn; Nedersaksen, -duitschland."

- ↑ (Dutch) Source on the Low Countries. (De Nederlanden)

- ↑ (Dutch) neder- corresponds with the English nether-, which means "low" or "down". See Online etymological dictionary. Entry: Nether.

- ↑ (Dutch) Etymologisch Woordenboek van het Nederlands entry "Diets".

- ↑ See the history section of the Vanderbilt family article, or visit this link.

- ↑ "It is a common mistake of Americans, or anglophones in general, to think that the 'van' in front of a Dutch name signifies nobility." (Source.); "Von may be observed in German names denoting nobility while the van, van der, van de and van den (whether written separately or joined, capitalized or not) stamp the bearer as Dutch and merely mean 'at', 'at the', 'of', 'from' and 'from the' (Source: Genealogy.com), (Institute for Dutch surnames, in Dutch)

- ↑ The Anglo-Saxon Church - Catholic Encyclopedia article

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 The Dutch Republic Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477-1806, ISBN 0-19-820734-4

- ↑ A 2004 study conducted by Statistics Netherlands shows that 50% of the population claim to belong to a Christian denomination, 9% to other denominations and 42% to none. In the same study 19% of the people claim go to church at least once a month, another 9% less than once a month, 72% hardly ever or never. Statistical Yearbook of the Netherlands 2006, page 43

- ↑ (Dutch) Religion in the Netherlands, by Statistics Netherlands.

- ↑ OSTSIEDLUNG

- ↑ Neumark

- ↑ Dutch and Flemish Colonization in Mediaeval Germany, by James Westfall Thompso

- ↑ Immigrants from the Netherlands in Siberia?

- ↑ Nomination VOC archives for Memory of the World Register

- ↑ Easternization of the West: Children of the VOC

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2003, "Population characteristics: Ancestry of Australia's population" (from Australian Social Trends, 2003). Retrieved September 1, 2006.

- ↑ How the Dutch became Americans, American Civil War (1861-1865).

Further reading

- Die Niederlande. Geschichte und Sprache der Nördlichen und Südlichen Niederlande. J. A Kossmann-Putto and E.H. Kossmann, 1993. (German for "The Netherlands. History and language of the Northern and Southern Netherlands")

- Dutch South Africa: early settlers at the Cape, 1652 – 1708. By John Hunt, Heather-Ann Campbell. Troubador Publishing Ltd 2005, ISBN 1904744958.

- Geschiedenis van de Nederlanden. By J.C.H. Blom et al. (Dutch for "History of the Low Countries")

- Handgeschreven wereld. Nederlandse literatuur en cultuur in de middeleeuwen. By D. Hogenelst and Frits van Oostrom, 1995, Amsterdam. (Dutch for "A handwritten world. Dutch literature and culture in the Middle Ages.")

- The Dutch in America, 1609 – 1974. By Gerald Francis De Jong. Twayne Publishers 1975, ISBN 0805732144

- The Dutch in Brazil, 1624-1654. By Charles R. Boxer. The Clarendon press, Oxford, 1957, ISBN 0208013385

- The Persistence of Ethnicity: Dutch Calvinist pioneers. By Rob Kroes. University of Illinois Press 1992, ISBN 0252019318

- The Undutchables, by White & Boucke, ISBN 1-888580-32-1.

- The Xenophobe's Guide to the Dutch. By Rodney Bolt. Oval Projects Ltd 1999, ISBN 190282525X

- Voor wie Nederland en Vlaanderen will leren kennen. By J. Wilmots and J. De Rooij, 1978, Hasselt/Diepenbeek. (Dutch for "For those who want to know about the Netherlands and Flanders")