Dusty Springfield

| Dusty Springfield | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Mary Isabel Catherine Bernadette O'Brien |

| Born | April 16, 1939 (Hampstead, London, England)[1] |

| Origin | Ealing, London, England |

| Died | March 2, 1999 (aged 59) Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, England |

| Genre(s) | Traditional pop, blue-eyed soul |

| Occupation(s) | Singer |

| Years active | 1958—1995 |

| Label(s) | Philips Records, Atlantic Records |

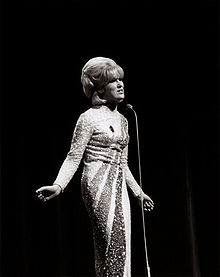

Mary Isabel Catherine Bernadette O'Brien[2] OBE (16 April 1939 – 2 March 1999), professionally known as Dusty Springfield, was an English pop singer.[3] Of the female artists of the British Invasion, Springfield made the biggest impression on the U.S. market.[4] From 1963 to 1970, she scored 18 singles in the Billboard Hot 100.[5] She was voted the Top British Female Artist by readers of New Musical Express in 1964, 1965,[6] and 1968.[7] Springfield is an inductee of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the UK Music Hall of Fame.[8] She was named among the 25 female rock artists of all time by readers of Mojo magazine (1999),[9] editors of Q magazine (2002),[10] and a panel of artists by the TV channel VH1 (2007).[11]

A fan of American soul music,[12] Dusty Springfield created a distinctive blue-eyed soul sound.[13][3] Her distinctive voice was described by Burt Bacharach as:"...three notes and you knew it was Dusty."[14] Her dashing, glamourous image was supported by a peroxided blonde beehive hairstyle,[2] heavy use of eyeliner,[8] and luscious evening gowns.[15]

Springfield began her solo career in 1963 with the Phil Spector-influenced pop/rock song "I Only Want To Be With You".[13] Her following chart hits included "I Just Don't Know What to Do with Myself" and "You Don't Have to Say You Love Me". She campaigned to bring little-known soul singers to a wider U.K. audience by devising and hosting the first British performances of top-selling Motown Records artists on The Sound of Motown, a special edition of the Ready Steady Go! TV series in 1965.[16][17][18] Her song "The Look of Love", written for Dusty Springfield by Burt Bacharach and Hal David, was featured in the scene of Ursula Andress seducing Peter Sellers in the film Casino Royale.[19] The song was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Song. The sudden changes of world pop music towards the experimentation of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, Summer of Love themes, and psychedelia left Springfield out of fashion.[20][5] To boost her credibility,[20] she went to Memphis, Tennessee to record an album of pop and soul music with Atlantic Records' production team of Jerry Wexler, Arif Mardin, and Tom Dowd. The LP Dusty in Memphis[21] received the Grammy Hall of Fame award in 2001 and was listed among the 100 Greatest Albums of All Time by Rolling Stone and VH1, readers of New Musical Express, and viewers of Channel 4. The standout track of the album, "Son of a Preacher Man", was an international Top 10 chart hit in 1969. The song was revived in 1994 by Quentin Tarantino[22] including it in the Pulp Fiction soundtrack,[23] which sold over three million copies.[24] Springfield's low period after Dusty in Memphis ended in 1987, when a collaboration with the Pet Shop Boys returned her to the top 20 of UK and U.S. charts with the singles "What Have I Done to Deserve This?", "Nothing Has Been Proved" and "In Private".[12] Springfield kept recording until she was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1995. She died on March 2, 1999.

Contents |

Biography

Mary Isabel Catherine Bernadette O'Brien[2] was born in West Hampstead, England to an Irish family[3], and was brought up in the West London borough of Ealing. The name "Dusty" was given to her when she was a child, as she had been a tomboy in her early years. Dusty's mother told her a lot about movies. Her tax consultant father[2] used to tap out rhythms on the back of her hand, encouraging the young Dusty to guess the musical piece. Springfield was brought up listening to a wide range of music, Gershwin, Rogers and Hart, Rogers and Hammerstein, Cole Porter, Count Basie, Duke Ellington and Glenn Miller, among others. She was a fan of American Jazz and the music of Peggy Lee, with a desire to sound like her. At age 11, she went into a local record shop in Ealing and made her first record, the Judy Garland Irving Berlin song "When The Midnight Choo Choo Leaves For Alabam".[25]

First bands (1958–63)

After finishing school in 1958, Springfield responded to the advertisement to join an "established sister act" Lana Sisters. With the vocal group, she developed the art of harmonising, learned microphone technique, recorded, did some television and played live both in the UK and at American Air Bases.[26]

In 1960 she left the band and formed the pop-folk trio the Springfields with her brother Dion O'Brien (now known as Tom Springfield) and Tim Feild (who was later replaced by Mike Hurst). The new trio chose the Springfields as their name during a rehearsal in a field in Somerset in spring. She reflected on her time in the Springfields as a time of jolly and loud singing that wasn't always in tune.[26] Intending to make an authentic American album, the Springfields travelled to Nashville to record the album Folk Songs from the Hills. During a stopover in New York City Springfield, already a fan of black vocal groups such as the Shirelles, heard "Tell Him" by the Exciters and was inspired by its sound.[26] This helped to turn Springfield's career from the folk and country sounds of the Springfields towards pop music rooted in rhythm and blues. In the spring of 1963, the Springfields recorded their last UK Top 5 hit, "Say I Won't Be There", before disbanding. They played their last concert in October 1963.

A Girl Called Dusty (1963–64)

Dusty Springfield's first single, the soul-tinged "I Only Want to Be with You", was released in November 1963. The song, Springfield's first flirtation with American soul,[12] was arranged by Ivor Raymonde and paid homage to Phil Spector's "Wall of Sound" production style.[27] The single rose to #4 in the British charts[28] and #12 on Billboard Hot 100[5]. The song was actually a "sure shot" pick on influential New York pop music station WMCA in December 1963, even before the station started playing the Beatles. The release eventually charted into the top 10 on WMCA's weekly top 25 countdown survey. It was #48 of the year 1964 of the Musicradio WABC Top.[29] The song was also the first record played on the BBC's Top of the Pops.[6]

As an apparently rushed work,[20] her debut album A Girl Called Dusty included mostly covers of her favorite songs by other performers.[20] On the album, the pounding orchestral arrangements by Ivor Raymonde and her first producer, Johnny Franz, drowned Springfield's voice, making it sound thin.[20] Among the songs were "Mama Said", "When the Lovelight Starts Shining Through His Eyes", "You Don't Own Me", and "Twenty-Four Hours from Tulsa".[6] The album reached UK #6 in May 1964.[30] The chart hits "Stay Awhile", "All Cried Out", and "Losing You" followed the same year.[28] In 1964, Springfield recorded two Burt Bacharach songs: "Wishin' and Hopin'", a U.S. Top 10 hit,[5] and "I Just Don't Know What to Do with Myself", which reached UK #3.[28]

Springfield's tour of South Africa was interrupted in December 1964, after she performed before an integrated audience at a theater near Cape Town. Her flouting of government segregation policy resulted in her deportation from the country.[6] The same year, she was voted Top Female British Artist in a New Musical Express poll, beating Lulu, Sandie Shaw, and Cilla Black.[20] Springfield received the award again the following year.[6]

1965 releases

In 1965 Springfield took part in the Italian Song Festival in Sanremo, failing to qualify to the final with two songs. In the competition, she heard the song "Io Che Non Vivo (Senza Te)".[31] The English version of the song, "You Don't Have to Say You Love Me", featured lyrics written by Springfield's friend and future manager, Vicki Wickham, and Simon Napier-Bell.[32] It reached UK #1[28] and U.S. #4 on the weekly Billboard Hot 100[5], and was #35 on the Billboard Top for 1966.[33] The song, which Springfield called "good old schmaltz",[32] was voted among the All Time Top 100 Songs by the listeners of BBC Radio 2 in 1999.

In 1965, she released three more UK Top 40 hits: "Your Hurtin' Kinda Love", "In the Middle of Nowhere" and Carole King's "Some of Your Lovin'".[28] These were not included on the album Ev'rything's Coming Up Dusty, featuring songs by Leslie Bricusse, Anthony Newley, Rod Argent, and Randy Newman, and a cover of the traditional Latin song, "La Bamba". The LP peaked at UK #6.[34]

The Sound of Motown (1965–66)

Because of her enthusiasm for Motown music, Springfield campaigned to get the little known American soul singers a better audience in the UK.[8] She hosted The Sound Of Motown, a Ready Steady Go! special edition, on April 28, 1965. The show was broadcast by Rediffusion TV from their Wembley Studios. Springfield opened the two parts of the show, performing "Wishin' and Hopin'" and "Can't Hear You No More", accompanied by Martha Reeves and the Vandellas and Motown's in-house band The Funk Brothers. Other guests included The Temptations, The Supremes, The Miracles, Stevie Wonder, and Marvin Gaye.[17] In 1994, guests of the 1965 show credited Dusty's championing of their music for popularizing American soul music in the UK in the documentary, Dusty Springfield. Full Circle.[35] Springfield released three additional UK Top 20 hits in 1966: "Little By Little", Carole King's "Going Back" and "All I See Is You".[28] In fall 1966, she hosted Dusty, a series of 6 BBC TV music and talk shows.[36] A compilation of her singles, Golden Hits, released in November 1966, reached UK #2.[37]

The Look of Love (1967)

The Bacharach-David composition "The Look of Love" was designed as a centerpiece for the spoof Bond movie Casino Royale. For one of the slowest-tempo hits of the sixties, Bacharach created the sultry by minor-seventh and major-seventh chord changes, while Hal David's lyrics epitomized longing and lust.[38] The track was recorded in two versions at the Philips Studios of London. The soundtrack version was recorded on January, 29, and the single release version on April 14.[39] The song is featured in the scene of Ursula Andress as Vesper Lynd persuading Peter Sellers as Evelyn Tremble,[19] seen through a man-size aquarium.[40] "The Look of Love" was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Song of 1967. The song was a Top 10 radio hit at the KGB and KHJ radio stations. As in 1967 Dusty had trouble with charting hits in the United States,[8] the song earned her highest place in the year's charts, #22.

Where Am I Going? (1967–68)

By the end of 1967, Dusty was becoming disillusioned with the show-business carousel on which she found herself trapped.[20] She appeared out of step with the Summer of Love and its attendant psychedelic music.[20] The second season of the BBC Dusty TV shows,[36] featuring performances of "Get Ready" and "I'll Try Anything", attracted a healthy audience, but was anathema to the sudden changes in pop music.[20] The comparatively progressive and prophetically titled Where Am I Going? attempted to redress this. Containing a jazzy, orchestrated version of "Sunny", and Jacques Brel's "If You Go Away", it was an artistic success, but flopped commercially.[20] In 1968 a similar fate awaited Dusty... Definitely.[20] On this her choice of material ranged from the rolling "Ain't No Sunshine" to the aching emotion of "I Think It's Gonna Rain Today".[20] In the same year Dusty had a UK Top 5 hit "I Close My Eyes and Count to Ten".[28] Her personal TV shows continued with the ITV series of It Must Be Dusty,[36] including a duet with Jimi Hendrix on the song "Mockingbird". In the same year, Roger Moore presented her third Top British Female Artist award, voted by the readers of New Musical Express.

Memphis sessions (1968–69)

In 1968, Carole King, one of Springfield's songwriters, embarked on a singing career of her own, while the chart-busting Bacharach-David partnership was foundering. Springfield's status in the music industry was further complicated by the progressive music revolution and the uncomfortable split between what was underground and fashionable, and what was pop and unfashionable.[20] In addition, her performing career was becoming bogged down on the UK touring circuit, which at that time largely consisted of working men's clubs and the hotel and cabaret circuit.[20] Hoping to reinvigorate her career and boost her credibility, Springfield signed with Atlantic Records,[20] home label of an idol of hers, Aretha Franklin. The Memphis sessions at the American Sound Studios[2] were recorded by the A team of Atlantic Records: producers Jerry Wexler, Tom Dowd, Arif Mardin,[21] the back-up vocal band Sweet Inspirations and the instrumental band Memphis Cats,[41] led by guitarist Reggie Young and bass player Tommy Cogbill.[21] The producers were the first to recognize that Springfield's natural soul voice should be placed at the fore, rather than competing with full string arrangements. Due to Springfield's pursuit of perfection and what Jerry Wexler called, a 'gigantic inferiority complex', her vocals were recorded later in New York.[6][42]

The LP Dusty in Memphis was reviewed by the Rolling Stone magazine as a:[21]

| “ | drifting, cool, smart soul album | ” |

and:[42]

| “ | ...blazing soul and sexual honesty...that transcended both race and geography. | ” |

The LP fell short of the UK Top 15 and peaked at #99 on the Billboard Top 200. Dusty in Memphis received the Grammy Hall of Fame award in 2001. The album was listed among the 100 Greatest Albums of All Time by panels of artists from Rolling Stone and VH1, readers of New Musical Express, and viewers of Channel 4.

The standout track of the album, "Son of a Preacher Man", reached #10 on UK, U.S. and international charts. Its European success peaked at #10 on the Austrian charts and at #3 on the Swiss charts.[43] The song was the 96th most popular song of 1969 in the United States.[44] In 1994, the song was revived by Quentin Tarantino on the Pulp Fiction soundtrack,[23] which sold over three million copies.[45]

Decline (1969–86)

In September and October 1969, Dusty Springfield hosted eight episodes of the BBC TV show Decidedly Dusty.[36] In 1970, Springfield released her second album for Atlantic Records, A Brand New Me, featuring songs written and produced by Gamble and Huff. The album yielded a Billboard Top 25 single, "A Brand New Me". In 2007, its British counterpart, From Dusty With Love was listed among the 1000 Albums to Hear Before You Die by the Guardian newspaper. A third album for the Atlantic label, titled Faithful and produced by Jeff Barry, was abandoned because of poor sales of singles slated for the LP. Most of the material recorded for the aborted album was released on the 1999 reissue of Dusty in Memphis on Rhino Records. Her next album, See All Her Faces, was released only in Britain, having none of the cohesion of her previous two albums. In 1972, Springfield signed a contract with ABC Dunhill Records, and the resulting album, Cameo, was released in 1973 with little publicity.

In 1974, Springfield recorded the theme song for the TV series The Six Million Dollar Man. Her second ABC Dunhill album was given the working title Elements and scheduled for release as Longing. The sessions were soon abandoned. A part of the material, including tentative and incomplete vocals, was released on the 2001 compilation Beautiful Soul. She put her career on hold in 1974, living reclusively in the United States to avoid scrutiny by British tabloids.[6] During this time she provided background vocals for Anne Murray's LP Together[12] and Elton John's LP Caribou, including the single "The Bitch is Back". Springfield released two albums on United Artists Records in the late '70s. The first was 1978's It Begins Again, produced by Roy Thomas Baker. The LP charted on both sides of the Atlantic and was well received by critics, but was not a commercial success. The 1979 album Living Without Your Love did slightly better.[12] In London, she recorded two singles for her British label, Mercury Records. The first was the disco-influenced "Baby Blue", which reached #61 in Britain. The second, "Your Love Still Brings Me to My Knees", was Springfield's final single for Philips Records. In autumn 1979, Springfield played her first club dates in eight years in New York.[12] On 3 December 1979, she performed a charity concert for a full house at The Royal Albert Hall, in the presence of Princess Margaret. She signed a U.S. deal with 20th Century Fox Records, which resulted in the single "It Goes Like It Goes". In 1980, Springfield recorded the song "Bits and Pieces", written by Dominic Frontiere and Norman Gimbel. Sections of the song are used twice in the film The Stunt Man. Springfield was uncharacteristically proud of her 1982 album White Heat, influenced by the New Wave genre. After the commercial failure of the album, she stopped drinking and tried to get her life back together.[6] She tried to revive her career again in 1985 by returning to the United Kingdom and signing to Peter Stringfellow's Hippodrome Records label. This resulted in the single "Sometimes Like Butterflies" and an appearance on Stringfellow's live television show. None of Dusty Springfield's recordings from 1971 to 1986 charted on the UK or U.S. Top 40.

Comeback (1987–94)

In 1987, she accepted an invitation from the Pet Shop Boys to sing with the duo's Neil Tennant on their single "What Have I Done to Deserve This?" and appear on the promotional video. The record rose to #2 on both the UK and U.S. charts. The song subsequently appeared on the Pet Shop Boys' album Actually, and both of their greatest hits collections. Springfield sang lead vocals on the Richard Carpenter track "Something in Your Eyes", recorded for Carpenter's album Time. Released as a single, it became a #12 Adult Contemporary hit in the United States. Springfield recorded a duet with B.J. Thomas, "As Long as We Got Each Other", which was used as the theme song for the U.S. sitcom Growing Pains.

A new compilation of Springfield's greatest hits, The Silver Collection, was issued in 1988. Springfield returned to the studio with the Pet Shop Boys, who produced her recording of their song "Nothing Has Been Proved", commissioned for the soundtrack of the film Scandal. Released as a single in early 1989, the song gave Springfield a UK Top 20 hit. So did its follow-up, the upbeat "In Private", written and produced by the Pet Shop Boys. She capitalised on this by recording the 1990 album Reputation, another UK Top 20 success. The writing and production credits for half the album, which included the two recent hit singles, went to the Pet Shop Boys, while the album's other producers included Dan Hartman. Before recording the Reputation album, Springfield decided to leave California for good, and by 1988, she had returned to Britain. In 1993, she was invited to record a duet with her former 1960s professional rival and friend, Cilla Black. The song, "Heart and Soul", appeared on Black's Through the Years album. In 1994, Springfield started recording the album A Very Fine Love for Sony Records. Some of the songs were written by well-known Nashville songwriters and produced with a typical country feel.

Illness and death (1994–99)

While recording her final album, A Very Fine Love, in January 1994 in Nashville, Springfield felt unwell. Upon returning to England a few months later, she was diagnosed with breast cancer. She received months of radiation treatment and, for a time, the cancer was in remission.[5] In 1995, in apparent good health again, Springfield set about promoting the album and gave a live performance of "Where Is a Woman to Go?" on the BBC television music show Later With Jools Holland, backed by Alison Moyet and Sinéad O'Connor. The last song Springfield recorded was the George and Ira Gershwin standard "Someone To Watch Over Me". The song was recorded in London in 1995 for an insurance company television advertisement. It was included on Simply Dusty (2000), the extensive anthology the singer had helped plan but did not live to see released. Cancer was detected again in the summer of 1996. After a fight, she was defeated by the illness in 1999. She died in Henley-on-Thames on the day she had been due to go to Buckingham Palace to receive her Order of the British Empire insignia. Before her death, officials of St James's Palace gave permission for the medal to be collected by Springfield's manager, Vicki Wickham. She duly presented it to the singer in hospital, where they had been joined by a small party of friends and relatives. Her induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame had been scheduled for 10 days after her death. Elton John helped induct Springfield into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, stating:[46]

| “ | I think she is the greatest white singer that there ever has been. | ” |

The singer's funeral service was attended by hundreds of fans and people from the music business, including Elvis Costello, Lulu, and the Pet Shop Boys. It took place in Oxfordshire, at the ancient parish church of St Mary the Virgin, in Henley-on-Thames, where Springfield had lived during her last years. A marker dedicated to her memory was placed in the church graveyard. Some of Springfield's ashes were buried at Henley, while the rest were scattered by her brother, Tom Springfield, at the Cliffs of Moher, County Clare, Ireland. In what was considered a very rare departure from royal protocol, Queen Elizabeth said she was 'saddened' to learn of Springfield's death.

Selected quotes from the British obituaries:

"....the carefully shaded emotions she brought to the music of her prime....... she was the only white woman singer worthy of being mentioned in the same breath as the great divas of 1960's soul music" Richard Williams, The Guardian

"The Queen of Pop is dead" The Daily Express

".....few would deny that Dusty Springfield was the finest female pop singer that Britain has ever produced" Mick Brown, The Daily Telegraph

"The finest female voice we ever had" The Independent

"....as much a part of 1960's Britain as the mini skirt...." The Times

"Dusty ended life as the Queen of Britpop" The Daily Mirror

"...the voice that haunted a generation" The Daily Mail

"The day the music died" The Guardian

Dusty Springfield's will provided care for her cat, Nicholas, including a marriage to the five-year-old female cat of a friend in a private ceremony later that spring.[47]

Personality

The conflict between Dusty Springfield's Catholic faith and her life affected her deeply.[48] Springfield's biographers and journalists have suggested she had two personas: shy, especially in the studio, Springfield was a perfectionist.[49] Male colleagues, who were unused to women taking control in the studio, labelled her 'difficult'.[48] She often produced her songs, but could not take credit for doing so, as it was seen as bad form.[50] Springfield's musical ear was finely tuned, but she could neither read nor write music.[51] This made it even harder for her to communicate with the session musicians. During her extensive vocal sessions, she repeatedly recorded short phrases and single words.[16][52] In her early career, much of her odd behaviour was carried out more or less in fun — like her famous food fights and hurling a box of crockery down the stairs. As the Springfield persona became more famous, she was indulged, pampered and spoiled, and plummeted into chronic drug and alcohol abuse. For much of the 1970s, living in Hollywood, Springfield alternately battled mental health and substance abuse issues. The seriousness of her increasingly frequent acts of self-harm resulted in her being hospitalized on numerous occasions.[52] Dusty Springfield had great love for animals, particularly cats. She was an advocate for several humane groups.[52] She also enjoyed maps, getting lost, and navigating her way out.[25]

Sexuality

The fact that Dusty Springfield was never in a publicly known relationship meant that the issue of her being bisexual continued to be raised throughout her life.[53] In 1970, Dusty told the Evening Standard:[53]

| “ | A lot of people say I'm bent, and I've heard it so many times that I've almost learned to accept it....I know I'm perfectly as capable of being swayed by a girl as by a boy. More and more people feel that way and I don't see why I shouldn't. | ” |

In the standards of year 1970, that was a very bold statement.[53] Three years later, she explained to the Los Angeles Free Press:[25]

| “ | I mean, people say that I'm gay, gay, gay, gay, gay, gay, gay, gay. I'm not anything. I'm just ... People are people.... I basically want to be straight.... I go from men to women; I don't give a shit. The catchphrase is: I can't love a man. Now, that's my hang-up. To love, to go to bed, fantastic; but to love a man is my prime ambition.... They frighten me. | ” |

Later she stated that she had enjoyed relationships with both men and women and "liked it".[54] After the comment, she avoided the issue in public. An occasional comment in the presence of her drag queen fans and Princess Margaret at the performance at the Royal Albert Hall in 1979:[55]

| “ | I am glad to see that royalty isn't confined to the box. | ” |

Dusty's 1981 live-in relationship with Canadian singer Carole Pope, burdened with drug and alcohol abuse and self-injury, was described in a chapter of Pope's 2000 autobiography Anti-Diva.[56]

Artistry

Dusty Springfield's distinctive voice was described by Burt Bacharach as:[57]

| “ | You could hear just three notes and you knew it was Dusty. | ” |

Allmusic has stated that the sultry intimacy and heartbreaking urgency of Springfield's voice transcended image and fashion.[5] Depending on the requirements of the song, she could be pop diva, soul siren or rock n' roll queen.[6] Influenced by American pop music,[12] she created a distinctive white soul sound.[13][3] While recording new songs, Springfield implored musicians to capture the passion of American songs she had heard.[6] Her soul inclinations resulted in her often performing as the only white singer on all-black bills in the 1960s.[6] She insisted that her white British session musicians copy precisely the instrumental playing styles of black American musicians.[16] Her covers of songs by African-American singers ranged from close copies to full reworkings.[16] She sang songs that their writers ordinarily would have offered to black vocalists.[13]

Dusty Springfield had her own way with her lyrics, described in a 1969 review of Dusty In Memphis by Rolling Stone journalist Greil Marcus on the example of the song "Wishin' and Hopin'" as:

| “ | ...a soft, sensual box (voice) that allowed her to combine syllables until they turned into pure cream.[13] | ” |

Rolling Stone magazine remarked that her songs had depth, while presenting direct and simple statements about love.[13] Dusty's performances were intimate moments with her audience, who used to sing along. In her own words, her special relationship with the listeners lifted her performance.[26] Springfield's joyful, dashing image[16] was supported by her trademark peroxided blonde beehive hairstyle[2] and evening gowns.[15]

Legacy

Springfield was one of the best-selling British singers in the 1960s.[12] She was voted the Top British Female Artist by the readers of the New Musical Express in 1964, 1965,[6] and 1968.[7] Of the female singers of the British Invasion of pop music in the sixties, Springfield made the biggest impression on the U.S. market,[58] scoring 18 songs in the Billboard Hot 100 from 1963 to 1970. She is an inductee of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the UK Music Hall of Fame.[8] She was placed among the 25 female rock artists of all time by the readers of Mojo magazine (1999),[59] editors of Q magazine (2002),[10] and a panel of artists by the VH1 TV channel (2007).[11] In 2008, Dusty appeared on the Rolling Stone's "100 Greatest Singers of All Time".

Discography

-

For more details on this topic, see Dusty Springfield discography.

|

Original studio albums[5] and maximum positions on UK albums chart:[28]

Greatest Hits

|

The singles listed below reached the Top 25 of the Billboard Hot 100:[5]

The following singles reached the Top 20 of the UK Singles Chart[60]:

|

Bibliography

- Dancing with Demons: The Authorised Biography of Dusty Springfield, Penny Valentine and Vicki Wickham, Hodder & Stoughton Ltd, Aug 2000, ISBN 0340766735 [61]

- Annie J. Randall associate professor of musicology at Bucknell University. Dusty! Queen of the Postmods. Oxford University Press 17 November, 2008 p.240 ISBN 9780195329438

References

- ↑ Alice R. Carr, ‘Springfield, Dusty (1939–1999)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, Oct 2007 www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/72120, accessed 5 July 2008.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 "Dusty Springfield". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Flashback: Dusty Springfield". Observer Music Monthly.

- ↑ The Harmony Illustrated Encyclopedia of Rock, Sixth Edition, Harmony Books, 1988, p. 162.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 "Dusty Springfield". Allmusic.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 "Dusty Springfield Biography. musicianguide.com site".

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "The History of The NME Awards.1968. nme.com site".

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 "Biography for Dusty Springfield. IMDB site".

- ↑ 1999 Mojo rocklist.net site

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "The lists of the Q magazine".

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "100 Women of Rock & Roll. vh1.com site".

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 "Son of the Preacher Man. The Rolling Stone magazine".

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 "Greil Marcus. Dusty in Memphis. The Rolling Stone magazine site".

- ↑ Entertainment Fans' farewell to Dusty BBC News site

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Dusty Springfield - Live at the Royal Albert Hall (1979). Yahoo! Movies site".

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Annie J. Randall (2005). "Dusty Springfield and the Motown Invasion". Institute for Studies in American Music Newsletter 35. http://depthome.brooklyn.cuny.edu/isam/NewsletF05/RandallF05.htm.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 ""Ready, Steady, Go!" The Sound of Motown (1965). IMDB site".

- ↑ Matt Chayt (1999). "So Long, Farewell, Aufwiedersehen, Goodbye". The Declaration. http://www.the-declaration.com/1999/03_25/features/goodbye.shtml.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Casino Royale. Turner Classic Movies site".

- ↑ 20.00 20.01 20.02 20.03 20.04 20.05 20.06 20.07 20.08 20.09 20.10 20.11 20.12 20.13 20.14 "Springfield, Dusty". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music. (1998). Muze UK.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 "Dusty In Memphis. The Rolling Stone magazine".

- ↑ Martin Kelner (21 November 2001). "Dusty Springfield". Martin Kelner.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Pulp Fiction-10th Anniversary 2-Disc Collector's Edition (1994). Rob Giles, 2005".

- ↑ Matt Everitt. "Pulp Fiction Soundtrack Expanded".

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Michele Kort (1999). "The Secret Life of Dusty Springfield". The Advocate. http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1589/is_1999_April_27/ai_54492600.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 "Dusty Springfield". Myspace Music.

- ↑ Chin, Brian (1999). Album notes for The Best of Dusty Springfield (The Millennium Collection) by Dusty Springfield [Inset]. USA: Mercury Records (314 538 851-2).

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 28.5 28.6 28.7 "UK Top 40 Hit Database".

- ↑ "The Musicradio WABC Top 100 of 1964".

- ↑ Sharon Mawer. Album chart history. 1964 The official UK charts company site

- ↑ Sanremo 1965 (15a Edizione) hitparadeitalia.it

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 "You Don't Have to Say You Love Me. Rolling Stone site".

- ↑ Chareborneranger presents the Billboard Top 100 for 1966

- ↑ Sharon Mawer. Album chart history. 1965 The official UK charts company site

- ↑ Dusty Springfield. Full Circle Documentary film. Vision Records, 1994

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 "Filmography by TV series for Dusty Springfield. IMDB site".

- ↑ Sharon Mawer. Album chart history. 1966 The official UK charts company site

- ↑ The Look of Love Allmusic

- ↑ "Dusty Springfield The 1960's".

- ↑ Synopsis for Casino Royale (1967)

- ↑ "Dusty in Memphis. The treble site".

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 "89) Dusty in Memphis". Rolling Stone.

- ↑ Dusty Springfield - Son of a Preacher Man Swiss Charts

- ↑ Chareborneranger presents the Billboard Top 100 for 1969

- ↑ Matt Everitt. "Pulp Fiction Soundtrack Expanded".

- ↑ Elton John Rock On The Net

- ↑ Pavement, Dusty Springfield and Supergrass in the Week in Weird The Rolling Stone magazine

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 "Dusty Springfield (Mary O'Brien). VelvetClub.com site".

- ↑ Charles Taylor (1997). "Mission Impossible: The perfectionist rock and soul of Dusty Springfield.". Boston Phoenix.

- ↑ The Wild, the Beautiful and the Rebellious Lesbian News site

- ↑ Michele Kort (1999). Fyne Times. pp. Issue 16.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 "Dusty Springfield. activemusician site".

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 "The Invention of Dusty Springfield. Woman of Repute site".

- ↑ "Dusty Springfield. Netmemorials.co.uk site".

- ↑ Dusty Springfield Live at the Royal Albert Hall. DVD Video. Eagle Rock Entertainment, 2005

- ↑ * Pope, Carole (2000). Anti diva : an autobiography. Toronto: Random House Canada. ISBN 0-679-31048-7.

- ↑ Entertainment Fans' farewell to Dusty BBC News site

- ↑ The Harmony Illustrated Encyclopedia of Rock, Sixth Edition, Harmony Books, 1988, p. 162.

- ↑ 1999 Mojo rocklist.net site

- ↑ Guinness British Hit Singles & Albums (19 ed.). 2006. p. 521.

- ↑ Review of Dancing with Demons, "You don't have to say you love me", The Observer, September 3, 2000, Barbara Ellen

External links

- Dusty Springfield at the Open Directory Project