Dr. Seuss

| Dr. Seuss | |

|---|---|

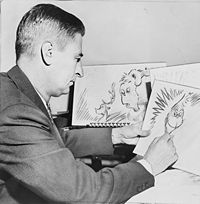

At work on a drawing of The Grinch for How the Grinch Stole Christmas!, in 1957. |

|

| Born | Theodor Seuss Geisel March 2, 1904 Springfield, Massachusetts, United States |

| Died | September 24, 1991 (aged 87) San Diego, California, United States |

| Pen name | Dr. Seuss, Theo. LeSieg, Rosetta Stone, Theophrastus Seuss |

| Occupation | Writer, cartoonist, animator |

| Nationality | United States |

| Genres | Children's literature |

| Notable work(s) | The Cat in the Hat Green Eggs and Ham One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish |

| Spouse(s) | Helen Palmer Geisel (1927–1967) Audrey Stone Dimond (1968– ) |

| Official website | |

Theodor Seuss Geisel (pronounced /ˈsɔɪs ˈɡaɪzəl/; March 2, 1904 – September 24, 1991) was an iconic and beloved American writer and cartoonist, better known by his pen name, Dr. Seuss (often pronounced /ˈsuːs/ or /ˈsjuːs/, though he himself said /ˈsɔɪs/).[1] He published over 60 children's books, which were often characterized by his imaginative characters, rhyme and frequent use of trisyllabic meter. His most notable books include the bestselling classics Green Eggs and Ham, The Cat in the Hat, and One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish. Numerous adaptations of his work have been created, including eleven television specials, three feature films and a Broadway musical.

Geisel also worked as an illustrator for advertising campaigns, most notably for Flit and Standard Oil, and as a political cartoonist for PM, a New York magazine. During World War II, he joined the Army to work in an animation department of the Air Force, where he wrote Design for Death, a film that later won the 1947 Academy Award for Documentary Feature.

Contents |

Life and career

Theodor Seuss Geisel was born on March 2, 1904 in Springfield, Massachusetts[2] to Henrietta Seuss and Theodor Robert Geisel, both of German descent[3]. His mother often chanted pie-selling rhymes to her children to make them fall asleep at night. Ted credited her for giving him both his ability and desire to create the rhymes for which he became so well known. He had two sisters, Marnie and Henrietta. Henrietta died of pneumonia at 18 months old. He attended Fremont Intermediate School from age 12 to age 14. His father was a parks superintendent in charge of Forest Park, a large park that included a zoo and was located three blocks from a library. Both Geisel's father and grandfather were brewmasters in Springfield, which may have influenced his views on Prohibition. As a freshman member of the Dartmouth College class of 1925, he became a member of Sigma Phi Epsilon. He also joined the Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern, eventually rising to the rank of editor-in-chief. (He took over the post from his close friend, author Norman MacLean.) However, after Geisel was caught throwing a drinking party (and thereby violating Prohibition laws), the school insisted that he resign from all extracurricular activities. In order to continue his work on the Jack-O-Lantern without the administration's knowledge, Geisel began signing his work with the pen name "Seuss" (which was both his middle name and his mother's maiden name). His first work signed as "Dr. Seuss" appeared after he graduated, six months into his work for humor magazine The Judge where his weekly feature Birdsies and Beasties appeared.[4]

The Seuss family pronounced their family name as Soice, to rhyme with voice, in line with the German pronunciation of eu (Geisel's maternal grandparents had emigrated from Germany). Alexander Liang, who served with Geisel on the staff of the Jack-O-Lantern and was later a professor at Dartmouth, illustrated this point. However, although Geisel himself has been quoted as saying that Seuss rhymes with voice, the name is often pronounced with an initial "s" sound and rhyming with "juice".[5] Geisel also used the pen name "Theo. LeSieg" (Geisel spelled backwards) for books he wrote but others illustrated.

He entered Lincoln College, Oxford, intending to earn a D.Phil in literature. At Oxford he met his future wife Helen Palmer; he married her in 1927, and returned to the United States without earning the degree. The "Dr." in his pen name is an acknowledgment of his father's unfulfilled hopes that Geisel would earn a doctorate at Oxford.

He began submitting humorous articles and illustrations to Judge, The Saturday Evening Post, Life, Vanity Fair, and Liberty. One notable "Technocracy Number" made fun of the Technocracy movement and featured satirical rhymes at the expense of Frederick Soddy. He became nationally famous from his advertisements for Flit, a common insecticide at the time. His slogan, "Quick, Henry, the Flit!" became a popular catchphrase. Geisel supported himself and his wife through the Great Depression by drawing advertising for General Electric, NBC, Standard Oil, and many other companies. He also wrote and drew a short-lived comic strip called Hejji in 1935.[4]

In 1937, while Geisel was returning from an ocean voyage to Europe, the rhythm of the ship's engines inspired the poem that became his first book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street. Geisel wrote three more children's books before World War II (see list of works below), two of which are, atypically for him, in prose.

As World War II began, Geisel turned to political cartoons, drawing over 400 in two years as editorial cartoonist for the left-wing New York City daily newspaper, PM. Geisel's political cartoons, later published in Dr. Seuss Goes to War, opposed the viciousness of Hitler and Mussolini and were highly critical of isolationists, most notably Charles Lindbergh, who opposed American entry into the war. One cartoon[6] depicted all Japanese Americans as latent traitors or fifth-columnists, while at the same time other cartoons deplored the racism at home against Jews and blacks that harmed the war effort. His cartoons were strongly supportive of President Roosevelt's conduct of the war, combining the usual exhortations to ration and contribute to the war effort with frequent attacks on Congress (especially the Republican Party), parts of the press (such as the New York Daily News and Chicago Tribune), and others for criticism of Roosevelt, criticism of aid to the Soviet Union, investigation of suspected Communists, and other offenses that he depicted as leading to disunity and helping the Nazis, intentionally or inadvertently. In 1942, Geisel turned his energies to direct support of the U.S. war effort. First, he worked drawing posters for the Treasury Department and the War Production Board. Then, in 1943, he joined the Army and was commander of the Animation Dept of the First Motion Picture Unit of the United States Army Air Forces, where he wrote films that included Your Job in Germany, a 1945 propaganda film about peace in Europe after World War II, Design for Death, a study of Japanese culture that won the Academy Award for Best Documentary in 1947, and the Private Snafu series of adult army training films. While in the Army, he was awarded the Legion of Merit. Geisel's non-military films from around this time were also well-received; Gerald McBoing-Boing won the Academy Award for Best Short Subject (Animated) in 1950.

Despite his numerous awards, Geisel never won the Caldecott Medal nor the Newbery. Three of his titles were chosen as Caldecott runners-up (now referred to as Caldecott Honor books): McElligot's Pool (1947), Bartholomew and the Oobleck (1949), and If I Ran the Zoo (1950).

After the war, Geisel and his wife moved to La Jolla, California. Returning to children's books, he wrote what many consider to be his finest works, including such favorites as If I Ran the Zoo, (1950), Scrambled Eggs Super! (1953), On Beyond Zebra! (1955), If I Ran the Circus (1956), and How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1957).

At the same time, an important development occurred that influenced much of Geisel's later work. In May 1954, Life magazine published a report on illiteracy among school children, which concluded that children were not learning to read because their books were boring. Accordingly, Geisel's publisher made up a list of 348 words he felt were important and asked Geisel to cut the list to 250 words and write a book using only those words. Nine months later, Geisel, using 236 of the words given to him, completed The Cat in the Hat. This book was a tour de force—it retained the drawing style, verse rhythms, and all the imaginative power of Geisel's earlier works, but because of its simplified vocabulary could be read by beginning readers. These books achieved significant international success and remain very popular.

Geisel went on to write many other children's books, both in his new simplified-vocabulary manner (sold as "Beginner Books") and in his older, more elaborate style. In 1982 Geisel wrote "Hunches in Bunches". The Beginner Books were not easy for Geisel, and reportedly he labored for months crafting them.

At various times Geisel also wrote books for adults that used the same style of verse and pictures: The Seven Lady Godivas; Oh, The Places You'll Go!; and You're Only Old Once.

On October 23, 1967, during a very difficult illness, Geisel's wife, Helen Palmer Geisel, committed suicide. Geisel married Audrey Stone Dimond on June 21, 1968. Geisel himself died, following several years of illness, in La Jolla, California on September 24, 1991. His ashes were scattered after he was cremated.

On December 1, 1995 UCSD's University Library Building was renamed Geisel Library in honor of Geisel and Audrey for the generous contributions they have made to the library and their devotion to improving literacy.[7]

Geisel was frequently confused, by the US Postal Service among others, with Dr. Suess (Hans Suess), his contemporary, living in the same locality, La Jolla. Their names have been linked together posthumously: the personal papers of Hans Suess are housed in the Geisel Library at UC San Diego.[8]

In 2002, the Dr. Seuss National Memorial Sculpture Garden opened in his birthplace of Springfield, Massachusetts; it features sculptures of Geisel and of many of his characters.

California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and First Lady Maria Shriver announced on May 28, 2008 that Geisel will be inducted into the California Hall of Fame, located at The California Museum for History, Women and the Arts. The induction ceremony will take place December 15 and his widow, Audrey will accept the honor in his place.

Though he devoted most of his life to writing children's books, he never had any children himself.

Political views

Geisel's early political cartoons show a passionate opposition to fascism, and he urged Americans to oppose it, both before and after the entry of the United States into World War II. In contrast, his cartoons tended to regard the fear of communism as overstated, finding the greater threat in the Dies Committee and those who threatened to cut America's "life line" to Stalin and Soviet Russia, the ones carrying "our war load".

Geisel's cartoons also called attention to the early stages of the Holocaust and denounced discrimination in America against African Americans and Jews, but he supported the Japanese American internment during World War II. Geisel himself experienced anti-semitism: in his college days, he was refused entry into certain circles because of a misperception that he was Jewish. Geisel's racist treatment of the Japanese and of Japanese Americans, whom he often failed to differentiate between, has struck many readers as a moral blind spot.[9] On the issue of the Japanese he is quoted as saying:

But right now, when the Japs are planting their hatchets in our skulls, it seems like a hell of a time for us to smile and warble: "Brothers!" It is a rather flabby battle cry. If we want to win, we’ve got to kill Japs?, whether it depresses John Haynes Holmes or not. We can get palsy-walsy afterward with those that are left.

—Theodor Geisel, quoted in Dr. Seuss Goes to War, by Dr. Richard H. Minear

After the war, though, Seuss was able to end his feelings of animosity, using his book Horton Hears a Who as a parable for the American post-war occupation of Japan, as well as dedicating the book to a Japanese friend.[10]

In 1948, after living and working in Hollywood for years, Geisel moved to La Jolla, California. It is said that when he went to register to vote in La Jolla, some Republican friends called him over to where they were registering voters, but Geisel said, "You my friends are over there, but I am going over here [to the Democratic registration]."

In his books

Though Seuss made a point of not beginning the writing of his stories with a moral in mind, stating that "kids can see a moral coming a mile off", he was not against writing about issues; he said "there's an inherent moral in any story"[11] and remarked that he was "subversive as hell".[12]

Many of Geisel's books are thought to express his views on a myriad of social and political issues: The Lorax (1971), about environmentalism and anti-consumerism; The Sneetches (1961), about racial equality; The Butter Battle Book (1984), about the arms race; Yertle the Turtle (1958), about anti-fascism and anti-authoritarianism; How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1957), about anti-materialism; and Horton Hears a Who! (1954), about anti-isolationism and internationalism.[10][1]

Shortly before the end of the 1972–1974 Watergate scandal, in which United States president Richard Nixon resigned, Geisel converted one of his famous children's books into a polemic. "Richard M. Nixon, Will You Please Go Now!" was published in major newspapers through the column of his friend Art Buchwald.[13]

Poetic meters

Geisel wrote most of his books in anapestic tetrameter, a poetic meter also employed by many poets of the English literary canon. This characteristic style of writing, which draws and pulls the reader into the text, is often suggested as one of the reasons that Geisel's writing was so well-received.[14][15]

Anapestic tetrameter consists of four rhythmic units, anapests, each composed of two weak beats followed by one strong beat; often, the first weak syllable is omitted, or an additional weak syllable is added at the end. An example of this meter can be found in Geisel's "Yertle the Turtle", from Yertle the Turtle and Other Stories:

- "And today the Great Yertle, that Marvelous he

- Is King of the Mud. That is all he can see."[16]

Geisel generally maintained this meter quite strictly, until late in his career, when he no longer maintained strict rhythm in all lines. The consistency of his meter was one of his hallmarks; the many imitators and parodists of Geisel are often unable to write in strict anapestic tetrameter, or are unaware that they should, and thus sound clumsy in comparison.

Some books by Geisel that are written mainly in anapestic tetrameter also contain many lines written in amphibrachic tetrameter, such as these from If I Ran the Circus:

- "All ready to put up the tents for my circus.

- I think I will call it the Circus McGurkus.

- "And NOW comes an act of Enormous Enormance!

- No former performer's performed this performance!"

Geisel also wrote verse in trochaic tetrameter, an arrangement of four units of a strong followed by a weak beat (for example, the title of One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish. The formula for trochaic meter permits the final weak position in the line to be omitted, which facilitates the construction of rhymes.

Geisel generally maintained trochaic meter only for brief passages, and for longer stretches typically mixed it with iambic tetrameter, which consists of a weak beat followed by a strong, and is generally considered easier to write. Thus, for example, the magicians in Bartholomew and the Oobleck make their first appearance chanting in trochees (thus resembling the witches of Shakespeare's Macbeth):

- "Shuffle, duffle, muzzle, muff"

then switch to iambs for the oobleck spell:

- "Go make the Oobleck tumble down

- On every street, in every town!"[17]

Artwork

Geisel's earlier artwork often employed the shaded texture of pencil drawings or watercolors, but in children's books of the postwar period he generally employed the starker medium of pen and ink, normally using just black, white, and one or two colors. Later books such as The Lorax used more colors.

Geisel's figures are often rounded and somewhat droopy. This is true, for instance, of the faces of the Grinch and of the Cat in the Hat. It is also true of virtually all buildings and machinery that Geisel drew: although these objects abound in straight lines in real life, for buildings, this could be accomplished in part through choice of architecture. For machines, for example, If I Ran the Circus includes a droopy hoisting crane and a droopy steam calliope.

Geisel evidently enjoyed drawing architecturally elaborate objects. His endlessly varied (but never rectilinear) palaces, ramps, platforms, and free-standing stairways are among his most evocative creations. Geisel also drew elaborate imaginary machines, of which the Audio-Telly-O-Tally-O-Count, from Dr. Seuss's Sleep Book, is one example. Geisel also liked drawing outlandish arrangements of feathers or fur, for example, the 500th hat of Bartholomew Cubbins, the tail of Gertrude McFuzz, and the pet for girls who like to brush and comb, in One Fish Two Fish.

Geisel's images often convey motion vividly. He was fond of a sort of "voilà" gesture, in which the hand flips outward, spreading the fingers slightly backward with the thumb up; this is done by Ish, for instance, in One Fish Two Fish when he creates fish (who perform the gesture themselves with their fins), in the introduction of the various acts of If I Ran the Circus, and in the introduction of the Little Cats in The Cat in the Hat Comes Back. He was also fond of drawing hands with interlocked fingers, which looked as though the character was twiddling their thumbs.

Geisel also follows the cartoon tradition of showing motion with lines, for instance in the sweeping lines that accompany Sneelock's final dive in If I Ran the Circus. Cartoonist's lines are also used to illustrate the action of the senses (sight, smell, and hearing) in The Big Brag and even of thought, as in the moment when the Grinch conceives his awful idea.

Recurring images

Geisel's early work in advertising and editorial cartooning produced sketches that received more perfect realization later in the children's books. Often, the expressive use to which Geisel put an image later on was quite different from the original.[18]

- An editorial cartoon of July 16, 1941[19] depicts a whale resting on the top of a mountain, as a parody of American isolationists, especially Charles Lindbergh. This was later rendered (with no apparent political content) as the Wumbus of On Beyond Zebra (1955). Seussian whales (cheerful and balloon-shaped, with long eyelashes) also occur in McElligot's Pool, If I Ran the Circus, and other books.

- Another editorial cartoon from 1941[20] shows a long cow with many legs and udders, representing the conquered nations of Europe being milked by Adolf Hitler. This later became the Umbus of On Beyond Zebra.

- The tower of turtles in a 1942 editorial cartoon[21] prefigures a similar tower in Yertle the Turtle. This theme also appeared in a Judge cartoon as one letter of a hieroglypic message, and in Geisel's short-lived comic strip Hejji. Geisel once stated that Yertle the Turtle was Adolf Hitler.[22]

- Little cats A B and C (as well as the rest of the alphabet) who spring from each other's hats appeared in a Ford ad.

- The connected beards in Did I Ever Tell You How Lucky You Are? appear frequently in Geisel's work, most notably in Hejji, which featured two goats joined at the beard, The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T, which featured two roller-skating guards joined at the beard, and a political cartoon in which Nazism and the America First movement are portrayed as "the men with the Siamese Beard."

- Geisel's earliest elephants were for advertising and had somewhat wrinkly ears, much as real elephants do.[23] With And to Think that I Saw it on Mulberry Street (1937) and Horton Hatches the Egg (1940), the ears became more stylized, somewhat like angel wings and thus appropriate to the saintly Horton. During World War II, the elephant image appeared as an emblem for India in four editorial cartoons.[24] Horton and similar elephants appear frequently in the postwar children's books.

- While drawing advertisements for Flit, Geisel became adept at drawing insects with huge stingers,[25] shaped like a gentle S-curve and with a sharp end that included a rearward-pointing barb on its lower side. Their facial expressions depict gleeful malevolence. These insects were later rendered in an editorial cartoon as a swarm of Allied aircraft[26] (1942), and again as the Sneedle of On Beyond Zebra, and yet again as the Skritz in I Had Trouble in Getting to Solla Sollew.

Publications

Over the course of his long career, Geisel wrote over 60 books. Though most were published under his well-known pseudonym, Dr. Seuss, he also authored over a dozen books as Theo. LeSieg and one as Rosetta Stone. As one of the most popular children's authors of all time, Geisel's books have topped many bestseller lists, sold over 222 million copies, and been translated into more than 15 languages.[27] In 2000, Publishers Weekly compiled a list of the best-selling children's books of all time; of the top 100 hardcover books, 16 were written by Geisel, including Green Eggs and Ham, at number 4, The Cat in the Hat, at number 9, and One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish, at number 13.[28] In the years after his death in 1991, several additional books have been published based on his sketches and notes; these include Hooray for Diffendoofer Day! and Daisy-Head Mayzie. Though they were all published under the name Dr. Seuss, only My Many Colored Days, originally written in 1973, was entirely by Geisel.

As Dr. Seuss

|

|

As Theo. LeSieg

|

|

As Rosetta Stone

- Because a Little Bug Went Ka-choo (Illustrated by Michael Frith, 1975)

Adaptations

For most of his career, Geisel was reluctant to have his characters marketed in contexts outside of his own books. However, he did allow for the creation of several animated cartoons, an art form in which he himself had gained experience during the Second World War, and gradually relaxed his policy as he aged.

The first adaptation of one of Geisel's works was a cartoon version of Horton Hatches the Egg, animated at Warner Brothers in 1942. Directed by Robert Clampett, it was presented as part of the Looney Tunes series, and included a number of gags not present in the original narrative, including a fish committing suicide and a Katharine Hepburn imitation by Maisie.

In 1959, Geisel authorized Revell, the well-known plastic model-making company, to make a series of "animals" that snapped together rather than being glued together, and which could be assembled, disassembled and re-assembled "in thousands" of ways. The series was called the "Dr. Seuss Zoo" and included Gowdy the Dowdy Grackle, Norval the Bashful Blinket, Tingo the Noodle Topped Stroodle and Roscoe the Many Footed Lion. The basic body parts were the same and all were interchangeable, and so it was possible for children to combine parts from various characters in essentially unlimited ways in creating their own animal characters (Revell encouraged this by selling Gowdy, Norval and Tingo together in a "Gift Set" as well as in individually). Revell also made a conventional glue-together "beginner's kit" of The Cat in the Hat.

In 1966, Geisel authorized the eminent cartoon artist Chuck Jones, his friend and former colleague from the war, to make a cartoon version of How the Grinch Stole Christmas!; Geisel was credited as a co-producer, along with Jones, under his real name, "Ted Geisel". The cartoon was very faithful to the original book, and is considered a classic by many to this day; it is often broadcast as an annual Christmas television special. In 1970, an adaptation of Horton Hears a Who! was directed by Chuck Jones for MGM.

From 1971 to 1982, Geisel wrote seven television specials, which were produced by DePatie-Freleng Enterprises and aired on CBS: The Cat in the Hat (1971), The Lorax (1972), Dr. Seuss on the Loose (1973), The Hoober-Bloob Highway (1975), Halloween is Grinch Night (1977), Pontoffel Pock, Where Are You? (1980), and The Grinch Grinches the Cat in the Hat (1982). Several of the specials were nominated for and won multiple Emmy Awards.

A Soviet paint-on-glass-animated short film called Welcome (an adaptation of Thidwick the Big-Hearted Moose) was made in 1986. The last adaptation of Geisel's works before he died was The Butter Battle Book, a television special based on the book of the same name, directed by adult animation legend Ralph Bakshi. Geisel himself called the special "the most faithful adaptation of his work."

After Geisel died of cancer at the age of 87 in 1991, his widow Audrey Geisel was placed in charge of all licensing matters. She approved a live-action feature film version of How the Grinch Stole Christmas! starring Jim Carrey, as well as a Seuss-themed Broadway musical called Seussical, and both premiered in 2000. The Grinch has had limited engagement runs on Broadway during the Christmas season, after premiering in 1998 (under the title How the Grinch Stole Christmas!) at the Old Globe Theatre in San Diego, where it has become a Christmas tradition. In 2003, another live-action film was released, this time an adaptation of The Cat in the Hat that featured Mike Myers as the title character. Audrey Geisel was vocal in her dislike of the film, especially the casting of Myers as the Cat in the Hat, and stated that there would be no further live-action adaptations of Geisel's books.[29] However, an animated CGI feature film adaptation of Horton Hears a Who! was approved, and was eventually released on March 14, 2008, to critical acclaim.

Two television programs have been adapted from Geisel's work. The first, The Wubbulous World of Dr. Seuss, was a mix of live-action and puppetry by Jim Henson Television, the producers of The Muppets. It aired for one season on Nickelodeon in the United States, from 1996 to 1997. The second, Gerald McBoing-Boing, is an animated television adaptation of Geisel's 1951 cartoon of the same name.[30] Produced in Canada by Cookie Jar Entertainment, it ran from 2005 to 2007.

Geisel's books and characters are also featured in Seuss Landing, one of many "islands" at the Islands of Adventure theme park in Orlando, Florida. In an attempt to match Geisel's visual style, there are reportedly "no straight lines in Seuss Landing".[31]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Menand, Louis (2002-12-23). "Cat People: What Dr. Seuss Really Taught Us". The New Yorker. Condé Nast Publications. Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ Register of Dr. Seuss Collection - MSS 0230

- ↑ Ancestry of Theodor Geisel

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Lambiek Comiclopedia. "Dr. Seuss".

- ↑ Pronouncing German Words in English 2

- ↑ Dr. Seuss (w, p, i). "Waiting for the Signal from Home" PM (February 13). .

- ↑ UCSD Libraries: Geisel Library

- ↑ Hans Suess Papers

- ↑ The Political Dr. Seuss Springfield Library and Museums Association

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Wood, Hayley and Ron Lamothe (interview) (August 2004). "Interview with filmmaker Ron Lamothe about The Political Dr. Seuss". MassHumanities eNews. Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities. Archived from the original on September 16, 2007. Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ Peter Bunzel (1959-04-06). "The Wacky World of Dr. Seuss Delights the Child—and Adult—Readers of His Books". Life (Chicago: Time Inc.). ISSN 0024-3019. OCLC 1643958. "Most of Geisel's books point a moral, though he insists he never starts with one. 'Kids,' he says, 'can see a moral coming a mile off and they gag at it. But there's an inherent moral in any story.' ".

- ↑ Cott, Jonathan (1983). "The Good Dr. Seuss" (Reprint). Pipers at the Gates of Dawn: The Wisdom of Children's Literature. New York: Random House. ISBN 9780394504643. OCLC 8728388.

- ↑ Buchwald, Art (1974-07-30). "Richard M. Nixon Will You Please Go Now!", The Washington Post, Katharine Weymouth, p. B01. Retrieved on 2008-09-17.

- ↑ Mensch, Betty; Alan Freeman (1987). Getting to Solla Sollew: The Existentialist Politics of Dr. Seuss. p. 30. "In opposition to the conventional—indeed, hegemonic—iambic voice, his metric triplets offer the power of a more primal chant which quickly draws the reader in with its relentless repetition.".

- ↑ Fensch, Thomas (ed.) (1997). Of Sneetches and Whos and the Good Dr. Seuss. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0786403888. OCLC 37418407.

- ↑ Dr. Seuss (1958). Yertle the Turtle and Other Stories. Random House. OCLC 18181636.

- ↑ Dr. Seuss (1949). Bartholomew and the Oobleck. Random House. OCLC 391115.

- ↑ UCSD. "Mandeville Special Collections Library, UC San Diego".

- ↑ Dr. Seuss (w, p, i). "The Isolationist" PM (July 16). .

- ↑ Dr. Seuss (w, p, i). "The head eats.. the rest gets milked" PM (May 19). .

- ↑ Dr. Seuss (w, p, i). "You can't build a substantial V out of turtles!" PM (March 21). .

- ↑ CNN.com (October 17, 1999). "Serious Seuss: Children's author as political cartoonist".

- ↑ Geisel, Theodor. "You can't kill an elephant with a pop gun!". L.P.C.Co.

- ↑ Theodor Geisel. "India List".

- ↑ Theodor Geisel. "Flit kills!".

- ↑ Theodor Geisel (w, p, i). "Try and pull the wings off these butterflies, Benito!" PM (November 11). .

- ↑ "Seussville: Biography". Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P.. Retrieved on 2008-08-11.

- ↑ Debbie Hochman Turvey (2001-12-17). "All-Time Bestselling Children's Books". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved on 2008-04-23.

- ↑ Associated Press (February 26, 2004). Seussentenial: 100 years of Dr. Seuss. msnbc.com. Retrieved on April 6, 2008.

- ↑ Abby Ellin (2005-10-02). "The Return of . . . Gerald McBoing Boing?". nytimes.com. The New York Times. Retrieved on 2008-04-07.

- ↑ Universal Orlando.com. The Cat in the Hat ride. Retrieved on April 6, 2008.

Further reading

- Cohen, Charles (2004). The Seuss, the Whole Seuss and Nothing But the Seuss: A Visual Biography of Theodor Seuss Geisel. Random House Books for Young Readers. ISBN 0375822488.

- Fensch, Thomas (ed.) (1997). Of Sneetches and Whos and the Good Dr. Seuss: Essays on the Writings and Life of Theodor Geisel. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0786403888.

- Geisel, Audrey (1995). The Secret Art of Dr. Seuss. Random House. ISBN 0679434488.

- Geisel, Theodor (1987). Dr. Seuss from Then to Now: A Catalogue of the Retrospective Exhibition. Random House. ISBN 0394892682.

- Geisel, Theodor; Richard Minnear (ed.) (2001). Dr. Seuss Goes to War: The World War II Editorial Cartoons of Theodor Seuss Geisel. New Press. ISBN 1565847040.

- Geisel, Theodor (2005). Theodor Seuss Geisel: The Early Works, Volume 1. Checker Book Publishing. ISBN 1933160012.

- Geisel, Theodor; Richard Marschall (ed.). The Tough Coughs as he Ploughs the Dough: Early Writings and Cartoons by Dr. Seuss. ISBN 0688065481.

- MacDonald, Ruth K. (1988). Dr. Seuss. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0805775242.

- Morgan, Judith; Neil Morgan (1995). Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel. Random House. ISBN 0679416862.

- Nel, Philip (2007). The Annotated Cat: Under the Hats of Seuss and His Cats. Random House. ISBN 9780375833694.

- Nel, Philip (2004). Dr. Seuss: American Icon. Continuum Publishing. ISBN 0826414346.

- Weidt, Maryann; Kerry Maguire (1994). Oh, the Places He Went. Carolrhoda Books. ISBN 0876146272.

External links

- Seussville site Random House

- Dr. Seuss biography on Lambiek Comiclopedia

- The Register of Dr. Seuss Collection UC San Diego

- The Advertising Artwork of Dr. Seuss UC San Diego

- Dr. Seuss Went to War: A Catalog of Political Cartoons UC San Diego

- Dr. Seuss' Commencement Speech Lake Forest College

- Dr. Seuss at the Internet Movie Database

- Dr. Seuss at Find A Grave Retrieved on 2008-07-26

|

||||||||||||||||||||