Donkey

| Donkey | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Conservation status | ||||||||||||||||

|

Domesticated

|

||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||||

| Equus asinus Linnaeus, 1758 |

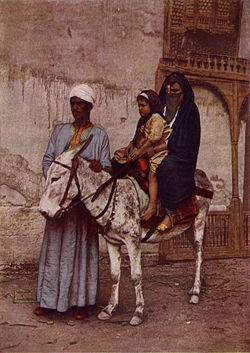

The donkey or ass, Equus asinus, is a member of the Equidae or horse family, and an odd-toed ungulate. The words donkey and ass are applied to the domesticated E. asinus. The animal considered to be its wild ancestor is the African Wild Ass, also E. asinus.

Colloquially, the term "ass" is often used today to refer to a larger, horse-sized animal, and "donkey" to a smaller, pony-sized one. In the western United States, a small donkey is sometimes called a burro (from the Spanish word for the animal).

A male donkey or ass is called a jack, a female a jenny, and offspring less than one year old, a foal (male: colt, female filly).

While different species of the Equidae family can interbreed, offspring are almost always sterile. Nonetheless, horse/donkey hybrids are popular for their durability and vigor. A mule is the offspring of a jack (male donkey) and a mare (female horse). The much rarer successful mating of a male horse and a female donkey produces a hinny.

Asses were first domesticated around 3000 BCE[1], approximately the same time as the horse, and have spread around the world. They continue to fill important roles in many places today and domesticated species are increasing in numbers (although the African wild ass and another relative, the Onager, are endangered species). As "beasts of burden" and companions, asses and donkeys have worked together with humans for centuries.

Contents |

Breeding

Jennies are pregnant for approximately 11 months, and usually give birth to one foal. Twins are very rare. Only about 1.7 percent of donkey pregnancies result in twins. Both twins survive in only about 14 percent of the cases.

Characteristics

Donkeys vary considerably in size, depending on breed and management. Most domestic donkeys range from 0.9 to over 1.4 m tall, though the Mammoth Jack breed is taller, and the Andalucian-Cordobesan breed of southern Spain can reach up to 1.6 m high.

Donkeys are adapted to marginal desert lands, and have many traits that are unique to the species as a result. Wild donkeys live separated from each other, unlike tight wild horse and feral horse herds. Donkeys have developed very loud vocalizations, which help keep in contact with other donkeys over the wide spaces of the desert. The best-known call is referred to a "bray," which can be heard for over three kilometers. Donkeys have larger ears than horses. Their longer ears may pick up more distant sounds, and may help cool the donkey's blood. Donkeys in the wild can defend themselves with a powerful kick of their hind legs as well as by biting and striking with their front feet.

Donkeys' tough digestive system is somewhat less prone to colic than that of horses, can break down near-inedible vegetation and extract moisture from food very efficiently. As a rule, donkeys need smaller amounts of feed than horses of comparable height and weight. Because they are easy keepers, if overfed, donkeys are also quite susceptible to developing a condition called laminitis.

Etymology of the name

Until recent times, the synonym ass was commonly used to refer to Equus asinus (e.g., as in jackass, meaning "male donkey"); ass has clear cognates in most other Indo-European languages. However, its homonymity in the United States with the vulgar term ass for "buttocks" probably influenced its gradual replacement by donkey when referring to Equus asinus. The word donkey is an etymologically obscure word. The first written use dates to 1785.[2] No credible cognate for donkey has yet been identified. Hypotheses on its derivation include the following:

- Perhaps a diminutive of dun (dull grayish-brown), a typical donkey colour.[3][2]

- Perhaps from the name Duncan.[4][2]

- Perhaps of imitative origin.[4]

History

The ancestors of the modern donkey are the Nubian and Somalian subspecies of African wild ass.[5][6] The African Wild Ass was domesticated around 4,000 BCE. The donkey became an important pack animal for people living in the Egyptian and Nubian regions as they can easily carry 20% to 30% of their own body weight and can also be used as a farming and dairy animal. By 1800 B.C., the ass had reached the Middle East, where the trading city of Damascus was referred to as the “City of Asses” in cuneiform texts. Syria produced at least three breeds of donkeys, including a saddle breed with a graceful, easy gait. These were favored by women.

For the Greeks, the donkey was associated with the Syrian god of wine, Dionysus. The Romans also valued the ass and would use it as a sacrificial animal.

Equines had become extinct in the Western Hemisphere at the end of the last Ice Age. However, horses and donkeys were brought back to the Americas by the Conquistadors. In 1495, the ass first appeared in the New World when Christopher Columbus brought four jacks and two jennys. It is from this bloodline that many of the mules which the Conquistadors used while they explored the Americas were produced. Shortly after America became independent, President George Washington imported the first mammoth jack stock into the country. Because the existing Jack donkeys in the New World at the time lacked the size and strength he sought to produce quality work mules, he imported donkeys from Spain and France, some standing over 1.63 m tall. One of the donkeys Washington received from the Marquis de Lafayette, named "Knight of Malta," stood 1.43 m and thus was regarded as a great disappointment. Viewing this donkey as unfit for producing mules, Washington instead bred Knight of Malta to his jennys and, in doing so, created an American line of Mammoth Jacks (a breed name that includes both males and females).

Despite these early appearances of donkeys in America, the donkey did not find widespread distribution in America until it was found useful as a pack animal by miners, particularly the gold prospectors, of the mid-1800s. Miners preferred this animal due to its ability to carry tools, supplies, and ore. Their sociable disposition and adaptation to human companionship allowed many miners to lead their donkeys without ropes. They simply followed behind their owner. As mining became less an occupation of the individual prospector and more of an industrial underground operation, the miners' donkeys lost their jobs, and many were simply turned loose into the American deserts. Descendants of these donkeys, now feral, can still be seen roaming the Southwest today.

By the early 20th century, donkeys began to be used less as working animals and instead kept as pets in the United States and other wealthier nations, while remaining an important work animal in many poorer regions. The donkey as a pet is best portrayed by the appearance of the miniature donkey in 1929. Robert Green imported miniature donkeys to the United States and was a lifetime advocate of the breed. Mr. Green is perhaps best quoted when he said "Miniature Donkeys possess the affectionate nature of a Newfoundland, the resignation of a cow, the durability of a mule, the courage of a tiger, and the intellectual capability only slightly inferior to man's." Standing only 32-40 inches, many families recognized the potential of miniature donkeys as pets and companions for their children.

Although the donkey fell from public notice and became viewed as a comical, stubborn beast which was considered “cute” at best, the donkey has recently regained some popularity in North America as a mount, for pulling wagons, and even as a guard animal. Some standard species are ideal for guarding herds of sheep against predators, since most donkeys have a natural wariness toward coyotes and other canines and will keep them away from the herd.

Economic use

Donkeys have a reputation for stubbornness, but this is due to some handlers' misinterpretation of their highly-developed sense of self-preservation. It is difficult to force or frighten a donkey into doing something it sees as contrary to its own best interest..

Although formal studies of their behaviour and cognition are rather limited, donkeys appear to be quite intelligent, cautious, friendly, playful, and eager to learn. They are often pastured or stabled with horses and ponies, and are thought to have a calming effect on nervous horses. If a donkey is introduced to a mare and foal, the foal will often turn to the donkey for support after it has been weaned from its mother.[7]

Once a person has earned their confidence they can be willing and companionable partners and very dependable in work. For this reason, they are now commonly kept as pets in countries where their use as beasts of burden has disappeared. They are also popular for giving rides to children in holiday resorts or other leisure contexts.

Present status

There are about 44 million donkeys today. China has the most with 11 million, followed by Pakistan, Ethiopia and Mexico. Some researchers think the real number is higher since many donkeys go uncounted.[8]

The vast majority of donkeys are used for the same types of work that they have been doing for 6000 years. Their most common role is for transport, whether riding, pack transport, or pulling carts. They may also be used for farm tillage, threshing, raising water, milling, and other jobs. Other donkeys are used to sire mules, as companions for horses, to guard sheep, and as pets. A few are milked or raised for meat[8]

The number of donkeys in the world continues to grow, as it has steadily throughout most of history. Some factors that today are contributing to this are increasing human population, progress in economic development and social stability in some poorer nations, conversion of forests to farm and range land, rising prices of motor vehicles and gasoline, and the donkeys' popularity as pets.[8][9]

In prosperous countries, the welfare of donkeys both at home and abroad has recently become a concern and a number of sanctuaries for retired and rescued donkeys have been set up. The largest is the Donkey Sanctuary of England, which also supports donkey welfare projects in Egypt, Ethiopia, India, Kenya, and Mexico.[10]

Donkeys in warfare

Donkeys have been used throughout history for transportation of supplies, pulling wagons, and, in a few cases, as riding animals. During World War I a British stretcher bearer, John Simpson Kirkpatrick, serving with the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, used a donkey named Duffy to rescue wounded soldiers, carrying them to safety in Gallipoli. There is a statue of John Simpson Kirkpatrick and his donkey in his home town, South Shields.

According to British food writer Matthew Fort, donkeys were until recently used in the Italian Army. The Mountain Fusiliers each had a donkey to carry their gear and in extreme circumstances, the animal could be eaten.[11] In 2006, security forces in Afghanistan prevented a man taking a donkey which he had laden with 30 kg (66lb) of explosives and a number of landmines, which would have been set off by a remote controlled detonator, from entering a town in Zabul Province.[12]

Types of donkeys

Domestic donkey breeds

An incomplete list of domestic donkey breeds includes the:

- Abyssinian Donkey

- American Spotted Donkey

- Cypriot Donkey

- Mammoth Donkey

- Mammoth Jack

- Miniature Mediterranean Donkey

- Poitou Donkey: The Poitou Donkey breed was developed in France for the sole purpose of producing mules. It is a large donkey breed with a very long shaggy coat and no dorsal stripe.

- Spotted Ass

- Standard Donkey

Burro

The Spanish brought donkeys, called "burros" in Spanish, to North America, where they were prized for their hardiness in arid country and became the beast of burden of choice by early prospectors in the Southwest United States. In the western United States the word "burro" is often used interchangeably with the word "donkey" by English speakers. Sometimes the distinction is made with smaller donkeys, descended from Mexican stock, called "burros," while those descended from stock imported directly from Europe are called "donkeys."

The wild burros (or more accurately, feral burros) on the western rangelands descend from animals that ran away, were abandoned, or were freed. Wild burros in the United States were protected by Pub.L. 92-195, the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971 (see also Kleppe v. New Mexico). These animals, considered to be a living legacy, are periodically at risk when there are severe drought conditions. To reduce herd populations and preserve grazing land, the Bureau of Land Management conducts roundups of burro herds and holds public auctions.

Wild burros can make good pets when treated well and trained properly. They are clever and curious. When trust has been established, they appreciate, and even seek, attention and grooming.

Donkey hybrids

A male donkey (jack) can be crossed with a female horse to produce a mule. A male horse can be crossed with a female donkey (jennet or jenny) to produce a hinny. A female donkey in the UK is called a mare, or jenny.

Horse-donkey hybrids are almost always sterile because horses have 64 chromosomes whereas donkeys have 62, producing offspring with 63 chromosomes. Mules are much more common than hinnies. This is believed to be caused by two factors, the first being proven in cat hybrids, that when the chromosome count of the male is the higher, fertility rates drop (as in the case of stallion x jennet). The lower progesterone production of the jenny may also lead to early embryonic loss. In addition, there are less-scientific reasons: Due to different mating behavior, jacks are often more willing to cover mares than stallions are to breed jennys. Further, mares are usually larger than jennys and thus have more room for the ensuing foal to grow in the womb, resulting in a larger animal at birth. It is commonly believed that mules are more easily handled and also physically stronger than hinnies, making them more desirable for breeders to produce, and it is unquestioned that mules are more common in total number.

The offspring of a zebra-donkey cross is called a zonkey, zebroid, zebrass, or zedonk;[13] zebra mule is an older term, but still used in some regions today. The foregoing terms generally refer to hybrids produced by breeding a male zebra to a female donkey. Zebra hinny, zebret and zebrinny all refer to the cross of a female zebra with a male donkey. Zebrinnies are rarer than zedonkies because female zebras in captivity are most valuable when used to produce full-blooded zebras.[14] There are not enough female zebras breeding in captivity to spare them for hybridizing; there is no such limitation on the number of female donkeys breeding.

For at least the past century, a few donkeys and burros in Mexico have been painted with white stripes to amuse tourists. These are not hybrids.

An animal which may look like a zebra-donkey hybrid because of its distinctly striped hindquarters and hind legs is the okapi, which has no relationship to either of those species. Okapi are most closely related to the giraffe. In addition to the rear stripes, okapi have some striping near the top of their forelegs.

Wild Ass, Onager, and Kiang

With domestication of almost all donkeys, few species now exist in the wild. Some of them are the African Wild Ass (Equus africanus) and its subspecies Somalian Wild Ass (Equus africanus somaliensis). The Asiatic wild ass or Onager, Equus hemionus, and its relative the Kiang, Equus kiang, are closely related wild species.

There were several other, now extinct (sub)species called the Yukon Wild Ass (Equus asinus lambei) and the European Ass (Equus Hydruntinus) which became extinct during the Neolithic. In the wild the asses can reach top speeds equalling zebras and even most horses.

Cultural references

The long history of human donkey use has created a rich store of cultural references.

Religion and myth

- Greek mythology includes the story of King Midas who judged against Apollo in favor of Pan during a musical contest, and had his ears changed to those of a donkey as punishment.

- In both Jewish and Christian traditions, the messiah (Jesus Christ in the later case) was often described as riding on a donkey. As noted, in the context of the Hebrew Bible this connoted wealth and affluence befitting the House of David, as at the time commoners are described as simply going on foot. However, in later times when the aristocracy used horses, depicting the messiah as riding a donkey came to have an opposite connotation, as indicating a simple, sober way of life and avoiding luxury. The same connotation is evident in the description of saints such as Francis of Assisi as riding donkeys.

- In contemporary Israel, the term "Messiah's Donkey" (Chamoro Shel Mashiach חמורו של משיח) stands at the center of a controversial religious-political doctrine, attributed to Rabbi Avraham Yitchak Hacohen Cook, under which it was the Heavenly-imposed "task" of secular Zionists to build up a Jewish State, but once the state is established they are fated to give place to the Religious who are ordained to lead the state. The secularists in this analogy are "The Donkey" while the religious who are fated to supplant them are a collective "Messiach". A book on the subject, published in 1998 by the militant secularist Sefi Rechlevsky, aroused a major controversy in the Israeli public opinion.[15]

- In Genesis the King of Shechem (the modern Nablus), killed by Jacob's sons, is called "Hamor" - showing that at the time this animal was held in high enough esteem that it was no disrespect for royalty to use its name as their first name. (See Dinah, Shechem, Animal names as first names in Hebrew).

- In Numbers 22:22-41 "The Lord opened the mouth of the donkey" (vs. 28) and it speaks to Balaam. In Judges 15:13-17 where the hero Samson slays Philistines with the jawbone of an ass. Additional references can be found in Deuteronomy 22:10, Job 11:12, Proverbs 26:3 and elsewhere.

- Muhammad, the prophet of Islam said that dogs and donkeys - if they pass in front of men in prayer - they will void or nullify that prayer.[16] He also said that "when you hear the braying of donkeys, seek Refuge with Allah from Satan for (their braying indicates) that they have seen a devil."[17]

- Several were buried in Hor-Aha's tomb

- The ass was a symbol of the Greek god Dionysus, particularly in relationship to his companion, Silenus.

- The most common Greek word for ass appears roughly 100 times in the Biblical text. In the Gospels, Jesus rides a donkey into Jerusalem (Mark 11:1 in which colt refers to a donkey colt).

- There are numerous references to the donkey ("hamor" or "chamor" חמור) in the Hebrew Bible, (Old Testament). It mostly appears reflecting the natural environment of Israel and as an aspect of the agricultural economy. Ownership of many donkeys is a sign of God’s blessing. The Bible often specifies whether a person rode donkeys, since this was used to indicate a person’s wealth in much the same way luxury cars do today. (Horses at that time were used solely for war, powerful kings such as Solomon being the only ones who could afford to import them from Egypt.)

- Traditionally, Mary is portrayed as riding a donkey while pregnant. Legend has it that the cross on the donkey’s shoulders comes from the shadow of Christ’s crucifixion, placing the donkey at the foot of the cross. It was once believed that hair cut from this cross and hung from a child’s neck in a bag would prevent fits and convulsions.

Fable and folklore

- European folklore claims that the tail of a donkey can be used to combat whooping cough or scorpion stings.

- An Indian tale has an ass dressed in a panther skin gave himself away by braying.

- One of Aesop's fables has an ass dressed in a lion skin who gives himself away by braying.

Literature

- Benjamin, the skeptical donkey from George Orwell's Animal Farm.

Any number of donkeys appear in world literary works.

- In Don Quixote, Sancho Panza rides a donkey named Rucio.

- Eeyore, the gloomy donkey from A.A. Milne's Winnie-the-Pooh books.

- In Pinocchio, naughty boys turn into donkeys and are sold off to hard labour by the evil Coachman. In the book, Pinocchio turns into a donkey for a time.

- Platero in Juan Ramon Jimenez's Platero and I

- Puzzle in C. S. Lewis's The Last Battle.

- In William Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, the character Bottom has his head turned into that of a donkey by Puck who was told by Oberon, king of the fairies, to change it.

Film

- The Disney film Fantasia (1940) features a Dionysian character on a donkey.

- A donkey is the central character of the film Au hasard Balthazar by Robert Bresson.

- Donkey is the name of a fictional donkey (voiced by Eddie Murphy) in the animated movies Shrek, Shrek 2 and Shrek the Third, all from DreamWorks Pictures.

Proverb and idiom

- A German proverb claims a donkey can wear a lion suit but its ear will still stick out and give it away.

- British colloquial expressions also include "donkey's years" which means for a long time or for many years, "to talk the hind leg off a donkey" means to tire somebody with one's talk.

- Classical Greek expressions about donkeys included: onos pros eortēn = "a donkey at the festival" (gets all the work); onos hyetai = "a donkey is rained on" (i.e. he is unaffected or insensitive), onos pros phatnēn = "a donkey at a feed trough" (like the English expression "in clover").

- English proverbs include "better be the head of an ass than the tail of a horse", "if an ass goes a-traveling, he'll not come back a horse", and "better ride on an ass that carries me home than a horse that throws me" (though all these are now obsolete).

Pub names

- The Jack and Jenny is a common pub-name in Britain.

Advertising

- Budweiser used a donkey in advertising during Super Bowl in 2004, called the Budweiser donkey he trains to be a Budweiser Clydesdale complete with hair extensions.

Insult and vulgarity

- In Arabic, حمار (ḥemar), meaning "donkey", is a derogatory term that refers to someone of very limited intelligence. Another usage is حمار شغل (ḥemar shuġl, literally "work donkey"), roughly equivalent in meaning to workaholic but with a distinct derogatory note and typically implying that the work is routine and non-creative; for example, someone might say, "Give that job to Ali, he's a work donkey anyway and he won't mind."

- Because of its connection with ignorance, in modern slang, referring to someone as a dumbass means that they are unintelligent. Many people would find this term vulgar and rude.

- In contrast, to refer to someone as a jackass in modern slang provides a connotation of being obnoxious, rude, and thoughtless, with or without the added connotation of stupidity. This usage is also considered vulgar. A less vulgar substitute is donkey itself.

- In football, especially in the United Kingdom, a player who is considered unskilful, and to rely overly on his physical attributes to cover up his technical shortcomings, is often dubbed a "donkey."

- The term "donkey" in British English is used in horse racing to refer to unsuccessful horses.

- The donkey has long been a symbol of ignorance. Examples can be found in Aesop's Fables, Apuleius's The Golden Ass (The Metamorphoses of Lucius Apuleius) and Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream.

- The term "donkey" is frequently used to refer to unskilled poker players, especially those playing in a predictably loose and unthinking fashion. Compare "patzer" in chess.

- The unmodified word ass and the adjectival form asinine have entered common use in the English language as terms used to describe a person who is stubborn, foolish, or disagreeable.

Politics

- In an election under a preferential voting system, a vote that simply writes down preferences in the order of the candidates (1 at the top, then 2, and so on) is called a donkey vote.

- The donkey is also the symbol for the Democratic Party of the United States, originating in a cartoon by Thomas Nast of Harper's Weekly (Nast also originated the elephant as the symbol of the Republican Party (United States).

See also

- Baudet de Poitou

- Burro Racing

- Exploding donkey

- Hinny

- Jenny (donkey) ("Jennet" was a type of medieval horse)

- Mule

- Ponui donkey

- Safe Haven for Donkeys in the Holy Land

Notes

- ↑ Rossel S, Marshall F et al. "Domestication of the donkey: Timing, processes, and indicators." PNAS 105(10):3715-3720. March 11, 2008. Abstract

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Grose Dict. Vulg. Tongue, "Donkey or Donkey Dick, a he or Jack-ass", Oxford English Dictionary, Second Edition, 1989 (OED Online, subscription, accessed 8th May 2008)

- ↑ Merriam-Webster Unabridged (MWU). (Online subscription-based reference service of Merriam-Webster, based on Webster's Third New International Dictionary, Unabridged. Merriam-Webster, 2002.) Headword donkey. Accessed 2007-09-13.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Houghton Mifflin (2000). The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed ed.). Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin. pp. page 535. ISBN 978-0-395-82517-4. http://www.houghtonmifflinbooks.com/epub/ahd4.shtml.

- ↑ J. Clutton-Brook, J. A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals 1999.

- ↑ Albano Beja-Pereira, "African Origins of the Domestic Donkey," in Science, 2004

- ↑ Donkeys

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Starkey, P. and M. Starkey. 1997. Regional and World trends in Donkey Populations. Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa (ATNESA)

- ↑ Blench, R. 2000. The History and Spread of Donkeys in Africa. Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa (ATNESA)

- ↑ The Donkey Sanctuary (DS). 2006. Website. (accessed December 2, 2006).

- ↑ Fort, Matthew (2005-06-20). Eating Up Italy: Voyages on a Vespa. HarperPerennial. ISBN 0007214812.

- ↑ "Afghan Police Stop Bombing Attack From Explosives-laden Donkey", Fox News (2006-06-08). Retrieved on 2007-11-04.

- ↑ American Donkey and Mule Society: Zebra Hybrids

- ↑ All About Zebra Hybrids

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Al-Nawawi, Sahih Muslim, 3-4:450-1; Ahmad Ibn Hanbal, Musnad, 5:194, 197, 202, 208; Abu Bakr Ibn al-‘Arabi, ‘Aridat al-Ahwadhi bi Sharh Sahih al-Tirmidhi (Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-‘Ilmiyya, n.d.), 1:133. All reported in El-Fadl.

- ↑ Sahih Bukhari 4:54:522

References

- Blench, R. 2000. The History and Spread of Donkeys in Africa. Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa (ATNESA)

- Clutton-Brook, J. 1999. A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521634954

- The Donkey Sanctuary (DS). 2006. Website. [2] (accessed December 2, 2006).

- Huffman, B. 2006. The Ultimate Ungulate Page: Equus asinus. (accessed December 2, 2006).

- International Museum of the Horse (IMH). 1998. Donkey. (accessed December 3, 2006).

- Nowak, R. M., and J. L. Paradiso. 1983. Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore, Maryland, USA : The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801825253

- Oklahoma State University (OSU). 2006. Breeds of Livestock. (accessed December 3, 2006).

- Starkey, P. and M. Starkey. 1997. Regional and World trends in Donkey Populations. Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa (ATNESA) [3]

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||