Determinant

In algebra, a determinant is a function depending on n that associates a scalar, det(A), to every n×n square matrix A. The fundamental geometric meaning of a determinant is a scale factor for measure when A is regarded as a linear transformation. Determinants are important both in calculus, where they enter the substitution rule for several variables, and in multilinear algebra.

For a fixed nonnegative integer n, there is a unique determinant function for the n×n matrices over any commutative ring R. In particular, this function exists when R is the field of real or complex numbers.

Contents |

Vertical bar notation

The determinant of a matrix A is also sometimes denoted by |A|. This notation can be ambiguous since it is also used for certain matrix norms and for the absolute value. However, often the matrix norm will be denoted with double vertical bars (e.g., ||A||) and may carry a subscript as well. Thus, the vertical bar notation for determinant is frequently used (e.g., Cramer's rule and minors).

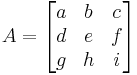

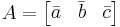

For example, for matrix

the determinant  might be indicated by

might be indicated by  or more explicitly as

or more explicitly as

That is, the square braces around the matrices are replaced with elongated vertical bars.

Finding determinants

2-by-2 matrices

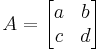

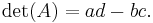

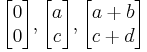

The 2×2 matrix,

has determinant

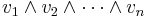

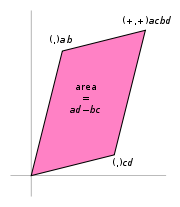

A matrix with real number entries also produces a representation of the oriented area of the parallelogram with vertices at (0,0), (a,b), (a + c, b + d), and (c,d). The oriented area is the same as the usual area, except that it is negative when the vertices are listed in clockwise order.

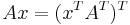

The assumption here is that a linear transformation is applied to row vectors as the vector-matrix product  , where

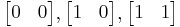

, where  is a column vector. The parallelogram in the figure is obtained by multiplying matrix A (which stores the co-ordinates of our parallelogram) with each of the row vectors

is a column vector. The parallelogram in the figure is obtained by multiplying matrix A (which stores the co-ordinates of our parallelogram) with each of the row vectors  and

and  in turn. These row vectors define the vertices of the unit square. With the more common matrix-vector product

in turn. These row vectors define the vertices of the unit square. With the more common matrix-vector product  the parallelogram has vertices at

the parallelogram has vertices at  and

and  (note that

(note that  ).

).

Thus when the determinant is equal to one, then the matrix represents an equi-areal mapping.

3-by-3 matrices

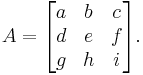

The 3×3 matrix:

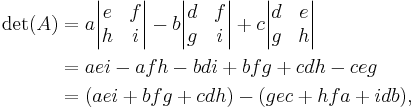

Using the cofactor expansion on the first row of the matrix we get:

which can be remembered, by applying the Rule of Sarrus, as the sum of the products of three diagonal north-west to south-east lines of matrix elements, minus the sum of the products of three diagonal south-west to north-east lines of elements when the copies of the first two columns of the matrix are written beside it as below:

Note that this mnemonic does not carry over into higher dimensions.

Applications

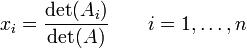

Determinants are used to characterize invertible matrices (i.e., a matrix is invertible if and only if it has a non-zero determinant), and to explicitly describe the solution to a system of linear equations with Cramer's rule. This rule is denoted

where the matrix  is the matrix formed by the insertion of the solution column vector.

is the matrix formed by the insertion of the solution column vector.

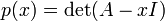

They can be used to find the eigenvalues of the matrix  through the characteristic polynomial

through the characteristic polynomial

where I is the identity matrix of the same dimension as A.

One often thinks of the determinant as assigning a number to every sequence of  vectors in

vectors in  , by using the square matrix whose columns are the given vectors. With this understanding, the sign of the determinant of a basis can be used to define the notion of orientation in Euclidean spaces. The determinant of a set of vectors is positive if the vectors form a right-handed coordinate system, and negative if left-handed.

, by using the square matrix whose columns are the given vectors. With this understanding, the sign of the determinant of a basis can be used to define the notion of orientation in Euclidean spaces. The determinant of a set of vectors is positive if the vectors form a right-handed coordinate system, and negative if left-handed.

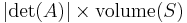

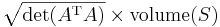

Determinants are used to calculate volumes in vector calculus: the absolute value of the determinant of real vectors is equal to the volume of the parallelepiped spanned by those vectors. As a consequence, if the linear map  is represented by the matrix

is represented by the matrix  , and

, and  is any measurable subset of

is any measurable subset of  , then the volume of

, then the volume of  is given by

is given by  . More generally, if the linear map

. More generally, if the linear map  is represented by the

is represented by the  -by-

-by- matrix

matrix  , and

, and  is any measurable subset of

is any measurable subset of  , then the

, then the  -dimensional volume of

-dimensional volume of  is given by

is given by  . By calculating the volume of the tetrahedron bounded by four points, they can be used to identify skew lines.

. By calculating the volume of the tetrahedron bounded by four points, they can be used to identify skew lines.

The volume of any tetrahedron, given its vertices a, b, c, and d, is (1/6)·|det(a − b, b − c, c − d)|, or any other combination of pairs of vertices that form a simply connected graph.

General definition and computation

The formal extension to arbitrary dimensions was made by Levi-Civita, using a pseudo-tensor symbol (Levi-Civita symbol). A definition of the determinant can be obtained by considering the following result.

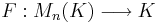

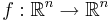

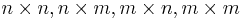

Theorem. Let Mn(K) denote the set of all  matrices over the field K. There exists exactly one function

matrices over the field K. There exists exactly one function

with the two properties:

is alternating multilinear with regard to columns;

is alternating multilinear with regard to columns; .

.

One can then define the determinant as the unique function with the above properties.

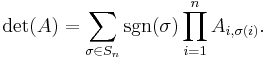

In proving the above theorem, one also obtains the Leibniz formula:

Here the sum is computed over all permutations  of the numbers {1,2,...,n}.

of the numbers {1,2,...,n}.  denotes the set of all n! permutations of the set S = {1,2,...,n}.

denotes the set of all n! permutations of the set S = {1,2,...,n}.  denotes the signature of the permutation

denotes the signature of the permutation  : +1 if

: +1 if  is an even permutation and −1 if it is odd.

is an even permutation and −1 if it is odd.  can also denote the signature of the number of inversions of the product of the permutation which is the approach used in some textbooks.

can also denote the signature of the number of inversions of the product of the permutation which is the approach used in some textbooks.

This formula contains  (factorial) summands, and it is therefore impractical to use it to calculate determinants for large

(factorial) summands, and it is therefore impractical to use it to calculate determinants for large  .

.

For small matrices, one obtains the following formulas:

- if

is a 1-by-1 matrix, then

is a 1-by-1 matrix, then

- if

is a 2-by-2 matrix, then

is a 2-by-2 matrix, then

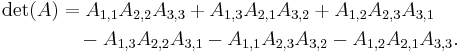

- for a 3-by-3 matrix

, the formula is more complicated and the shape of the Sarrus' scheme:

, the formula is more complicated and the shape of the Sarrus' scheme:

It is also possible to consider 0-by-0 matrices. There is only one 0-by-0 matrix and its determinant is one.[1]

In general, determinants can be computed using Gaussian elimination using the following rules:

- If

is a triangular matrix, i.e.

is a triangular matrix, i.e.  whenever

whenever  or, alternatively, whenever

or, alternatively, whenever  , then

, then  (the product of the diagonal entries of

(the product of the diagonal entries of  ).

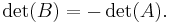

). - If

results from

results from  by interchanging two rows or columns, then

by interchanging two rows or columns, then

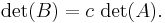

- If

results from

results from  by multiplying one row or column with the number

by multiplying one row or column with the number  , then

, then

- If

results from

results from  by adding a multiple of one row to another row, or a multiple of one column to another column, then

by adding a multiple of one row to another row, or a multiple of one column to another column, then

Explicitly, starting out with some matrix, use the last three rules to convert it into a triangular matrix, then use the first rule to compute its determinant.

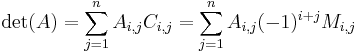

It is also possible to expand a determinant along a row or column using Laplace's formula, which is efficient for relatively small matrices. To do this along row  , say, we write

, say, we write

where the  represent the matrix cofactors, i.e.

represent the matrix cofactors, i.e.  is

is  times the minor

times the minor  , which is the determinant of the matrix that results from

, which is the determinant of the matrix that results from  by removing the

by removing the  -th row and the

-th row and the  -th column, and

-th column, and  is the length of the matrix.

is the length of the matrix.

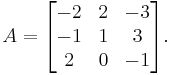

Example

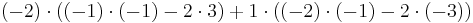

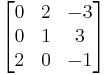

Suppose we want to compute the determinant of

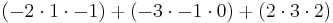

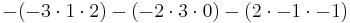

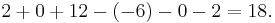

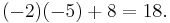

We can go ahead and use the Leibniz formula directly:

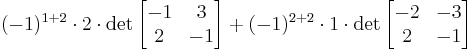

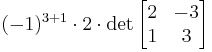

Alternatively, we can use Laplace's formula to expand the determinant along a row or column. It is best to choose a row or column with many zeros, so we will expand along the second column:

A third way (and the method of choice for larger matrices) would involve the Gauss algorithm. When doing computations by hand, one can often shorten things dramatically by cleverly adding multiples of columns or rows to other columns or rows; this does not change the value of the determinant, but may create zero entries which simplifies the subsequent calculations. In this example, adding the second column to the first one is especially useful:

and this determinant can be quickly expanded along the first column:

Properties

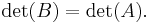

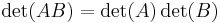

The determinant is a multiplicative map in the sense that

for all n-by-n matrices

for all n-by-n matrices  and

and  .

.

This is generalized by the Cauchy-Binet formula to products of non-square matrices.

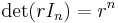

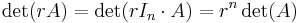

It is easy to see that  and thus

and thus

for all

for all  -by-

-by- matrices

matrices  and all scalars

and all scalars  .

.

A matrix over a commutative ring R is invertible if and only if its determinant is a unit in R. In particular, if A is a matrix over a field such as the real or complex numbers, then A is invertible if and only if det(A) is not zero. In this case we have

Expressed differently: the vectors v1,...,vn in Rn form a basis if and only if det(v1,...,vn) is non-zero.

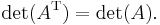

A matrix and its transpose have the same determinant:

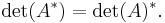

The determinants of a complex matrix and of its conjugate transpose are conjugate:

(Note the conjugate transpose is identical to the transpose for a real matrix)

The determinant of a matrix  exhibits the following properties under elementary matrix transformations of

exhibits the following properties under elementary matrix transformations of  :

:

- Exchanging rows or columns multiplies the determinant by −1.

- Multiplying a row or column by

multiplies the determinant by

multiplies the determinant by  .

. - Adding a multiple of a row or column to another leaves the determinant unchanged.

This follows from the multiplicative property and the determinants of the elementary matrix transformation matrices.

If  and

and  are similar, i.e., if there exists an invertible matrix

are similar, i.e., if there exists an invertible matrix  such that

such that  =

=  , then by the multiplicative property,

, then by the multiplicative property,

This means that the determinant is a similarity invariant. Because of this, the determinant of some linear transformation T : V → V for some finite dimensional vector space V is independent of the basis for V. The relationship is one-way, however: there exist matrices which have the same determinant but are not similar.

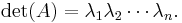

If  is a square

is a square  -by-

-by- matrix with real or complex entries and if λ1,...,λn are the (complex) eigenvalues of

matrix with real or complex entries and if λ1,...,λn are the (complex) eigenvalues of  listed according to their algebraic multiplicities, then

listed according to their algebraic multiplicities, then

This follows from the fact that  is always similar to its Jordan normal form, an upper triangular matrix with the eigenvalues on the main diagonal.

is always similar to its Jordan normal form, an upper triangular matrix with the eigenvalues on the main diagonal.

Useful identities

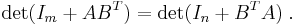

Sylvester's determinant theorem states that for any m-by-n matrices A and B,

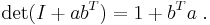

For the case of (column) vectors a and b, this equality becomes

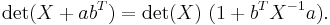

With X a nonsingular m-by-m matrix, this last expression generalizes to

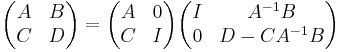

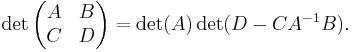

Block matrices

Suppose,  are

are  matrices respectively. Then

matrices respectively. Then

This can be seen from the Leibniz formula or by induction on n. Employing the following identity

leads to

A similar identity with  factored out can be derived analogously.[3]

factored out can be derived analogously.[3]

If  are diagonal matrices, then

are diagonal matrices, then

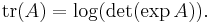

Relationship to trace

From this connection between the determinant and the eigenvalues, one can derive a connection between the trace function, the exponential function, and the determinant:

Performing the substitution  in the above equation yields

in the above equation yields

which is closely related to the Fredholm determinant. Similarly,

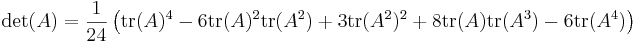

For n-by-n matrices there are the relationships:

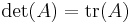

- Case n = 1:

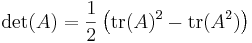

- Case n = 2:

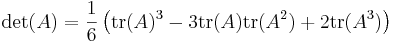

- Case n = 3:

- Case n = 4:

which are closely related to Newton's identities.

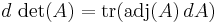

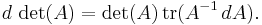

Derivative

The determinant of real square matrices is a polynomial function from  to

to  , and as such is everywhere differentiable. Its derivative can be expressed using Jacobi's formula:

, and as such is everywhere differentiable. Its derivative can be expressed using Jacobi's formula:

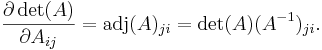

where adj(A) denotes the adjugate of A. In particular, if A is invertible, we have

In component form, these are

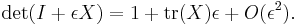

When  is a small number these are equivalent to

is a small number these are equivalent to

The special case where  is equal to the identity matrix

is equal to the identity matrix  yields

yields

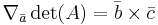

A useful property in the case of 3 x 3 matrices is the following:

A may be written as  where

where  ,

,  ,

,  are vectors, then the gradient over one of the three vectors may be written as the cross product of the other two:

are vectors, then the gradient over one of the three vectors may be written as the cross product of the other two:

Abstract formulation

An n × n square matrix A may be thought of as the coordinate representation of a linear transformation of an n-dimensional vector space V. Given any linear transformation

we can define the determinant of A as the determinant of any matrix representation of A. This is a well-defined notion (i.e. independent of a choice of basis) since the determinant is invariant under similarity transformations.

As one might expect, it is possible to define the determinant of a linear transformation in a coordinate-free manner. If V is an n-dimensional vector space, then one can construct its top exterior power ΛnV. This is a one-dimensional vector space whose elements are written

where each vi is a vector in V and the wedge product ∧ is antisymmetric (i.e., u∧u = 0). Any linear transformation A : V → V induces a linear transformation of ΛnV as follows:

Since ΛnV is one-dimensional this operation is just multiplication by some scalar that depends on A. This scalar is called the determinant of A. That is, we define det(A) by the equation

One can check that this definition agrees with the coordinate-dependent definition given above.

Algorithmic implementation

- The naive method of implementing an algorithm to compute the determinant is to use Laplace's formula for expansion by cofactors. This approach is extremely inefficient in general, however, as it is of order n! (n factorial) for an n×n matrix M.

- An improvement to order n3 can be achieved by using LU decomposition to write M = LU for triangular matrices L and U. Now, det M = det LU = det L det U, and since L and U are triangular the determinant of each is simply the product of its diagonal elements. Alternatively one can perform the Cholesky decomposition if possible or the QR decomposition and find the determinant in a similar fashion.

- Since the definition of the determinant does not need divisions, a question arises: do fast algorithms exist that do not need divisions? This is especially interesting for matrices over rings. Indeed algorithms with run-time proportional to n4 exist. An algorithm of Mahajan and Vinay, and Berkowitz is based on closed ordered walks (short clow). It computes more products than the determinant definition requires, but some of these products cancel and the sum of these products can be computed more efficiently. The final algorithm looks very much like an iterated product of triangular matrices.

- What is not often discussed is the so-called "bit complexity" of the problem, i.e. how many bits of accuracy you need to store for intermediate values. For example, using Gaussian elimination, you can reduce the matrix to upper triangular form, then multiply the main diagonal to get the determinant (this is essentially a special case of the LU decomposition as above), but a quick calculation will show that the bit size of intermediate values could potentially become exponential. One could talk about when it is appropriate to round intermediate values, but an elegant way of calculating the determinant uses the Bareiss Algorithm, an exact-division method based on Sylvester's identity to give a run time of order n3 and bit complexity roughly the bit size of the original entries in the matrix times n.

History

Historically, determinants were considered before matrices. Originally, a determinant was defined as a property of a system of linear equations. The determinant "determines" whether the system has a unique solution (which occurs precisely if the determinant is non-zero). In this sense, determinants were first used in Chinese mathematics textbook The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art (九章算術, Chinese scholars, around the 3rd century BC). In Europe, two-by-two determinants were considered by Cardano at the end of the 16th century and larger ones by Leibniz and, in Japan, by Seki about 100 years later.[5][6]

In Japan, determinants were introduced to study elimination of variables in systems of higher-order algebraic equations. They used it to give short-hand representation for the resultant. After the first work by Seki in 1683, Laplace's formula was given by two independent groups of scholars: Tanaka, Iseki (算法発揮, Sampo-Hakki, published in 1690) and Seki, Takebe, Takebe (大成算経, taisei-sankei, written at least before 1710). However, doubts have been raised about how much they recognized the determinant as an independent object.

In Europe, Cramer (1750) added to the theory, treating the subject in relation to sets of equations. The recurrent law was first announced by Bézout (1764).

It was Vandermonde (1771) who first recognized determinants as independent functions.[5] Laplace (1772) [7][8] gave the general method of expanding a determinant in terms of its complementary minors: Vandermonde had already given a special case. Immediately following, Lagrange (1773) treated determinants of the second and third order. Lagrange was the first to apply determinants to questions of elimination theory; he proved many special cases of general identities.

Gauss (1801) made the next advance. Like Lagrange, he made much use of determinants in the theory of numbers. He introduced the word determinants (Laplace had used resultant), though not in the present signification, but rather as applied to the discriminant of a quantic. Gauss also arrived at the notion of reciprocal (inverse) determinants, and came very near the multiplication theorem.

The next contributor of importance is Binet (1811, 1812), who formally stated the theorem relating to the product of two matrices of m columns and n rows, which for the special case of m = n reduces to the multiplication theorem. On the same day (November 30, 1812) that Binet presented his paper to the Academy, Cauchy also presented one on the subject. (See Cauchy-Binet formula.) In this he used the word determinant in its present sense[9][10], summarized and simplified what was then known on the subject, improved the notation, and gave the multiplication theorem with a proof more satisfactory than Binet's.[5][11] With him begins the theory in its generality.

The next important figure was Jacobi[6] (from 1827). He early used the functional determinant which Sylvester later called the Jacobian, and in his memoirs in Crelle for 1841 he specially treats this subject, as well as the class of alternating functions which Sylvester has called alternants. About the time of Jacobi's last memoirs, Sylvester (1839) and Cayley began their work.[12][13]

The study of special forms of determinants has been the natural result of the completion of the general theory. Axisymmetric determinants have been studied by Lebesgue, Hesse, and Sylvester; persymmetric determinants by Sylvester and Hankel; circulants by Catalan, Spottiswoode, Glaisher, and Scott; skew determinants and Pfaffians, in connection with the theory of orthogonal transformation, by Cayley; continuants by Sylvester; Wronskians (so called by Muir) by Christoffel and Frobenius; compound determinants by Sylvester, Reiss, and Picquet; Jacobians and Hessians by Sylvester; and symmetric gauche determinants by Trudi. Of the text-books on the subject Spottiswoode's was the first. In America, Hanus (1886), Weld (1893), and Muir/Metzler (1933) published treatises.

See also

- Sylvester's determinant theorem

- Matrix determinant lemma

- Permanent

- Minor (linear algebra)

- Trace (linear algebra)

- Slater determinant

References

- ↑ de Boor, Carl (1990), "An empty exercise", ACM SIGNUM Newsletter 25 (2): 3–7, doi:, http://ftp.cs.wisc.edu/Approx/empty.pdf.

- ↑ Proofs can be found in http://web.archive.org/web/20080113084601/http://www.ee.ic.ac.uk/hp/staff/www/matrix/proof003.html

- ↑ These identities were taken http://www.ee.ic.ac.uk/hp/staff/www/matrix/proof003.html

- ↑ This is a special case of the theorem published in http://www.mth.kcl.ac.uk/~jrs/gazette/blocks.pdf

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Campbell, H: "Linear Algebra With Applications", pages 111-112. Appleton Century Crofts, 1971

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Eves, H: "An Introduction to the History of Mathematics", pages 405, 493-494, Saunders College Publishing, 1990.

- ↑ Expansion of determinants in terms of minors: Laplace, Pierre-Simon (de) "Researches sur le calcul intégral et sur le systéme du monde," Histoire de l'Académie Royale des Sciences (Paris), seconde partie, pages 267-376 (1772).

- ↑ Muir, Sir Thomas, The Theory of Determinants in the Historical Order of Development [London, England: Macmillan and Co., Ltd., 1906].

- ↑ The first use of the word "determinant" in the modern sense appeared in: Cauchy, Augustin-Louis “Memoire sur les fonctions qui ne peuvent obtenir que deux valeurs égales et des signes contraires par suite des transpositions operées entre les variables qu'elles renferment," which was first read at the Institute de France in Paris on November 30, 1812, and which was subsequently published in the Journal de l'Ecole Polytechnique, Cahier 17, Tome 10, pages 29-112 (1815).

- ↑ Origins of mathematical terms: http://members.aol.com/jeff570/d.html

- ↑ History of matrices and determinants: http://www-history.mcs.st-and.ac.uk/history/HistTopics/Matrices_and_determinants.html

- ↑ The first use of vertical lines to denote a determinant appeared in: Cayley, Arthur "On a theorem in the geometry of position," Cambridge Mathematical Journal, vol. 2, pages 267-271 (1841).

- ↑ History of matrix notation: http://members.aol.com/jeff570/matrices.html

External links

- MIT Linear Algebra Lecture on Determinants

- Linear Systems Chapter from "Fundamental Problems of Algorithmic Algebra" Chee Yap's chapter on Linear Systems describing implementation aspects of Determinant computation.

- Mahajan, Meena and V. Vinay, “Determinant: Combinatorics, Algorithms, and Complexity”, Chicago Journal of Theoretical Computer Science, v. 1997 article 5 (1997).

- Online Matrix Calculator Online Matrix calculator.

- Linear algebra: determinants. Compute determinants of matrices up to order 6 using Laplace expansion you choose.