Demographics of the People's Republic of China

| Demographics of the People's Republic of China | |

|---|---|

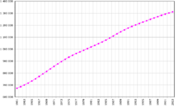

Population of China, 1961-2003 |

|

| Size: | 1,321,000,000 (2007 est.)(rounded) |

| Growth: | 0.629% (2008 est.) |

| Birth: | 13.71 births/1,000 population (2008 est.) |

| Death: | 7.03 deaths/1,000 population (2008 est.) |

| Life expectancy: | 73.18 years (2008 est.) |

| Life expectancy(m): | 71.37 years (2008 est.) |

| Life expectancy(f): | 75.18 years (2008 est.) |

| Fertility: | 1.77 children born/woman (2008) |

| Age Structure: | |

| 0-14 years: | 20.1% (male 142,085,665/female 125,300,391) (2008 est.) |

| 15-64 years: | 71.9% (male 491,513,378/female 465,020,030) (2008 est.) |

| 65-0ver years: | 8% (male 50,652,480/female 55,472,661) (2008 est.) |

| Sex Ratio: | |

| At birth: | 1.11 male(s)/female (2008 est.) |

| Under 15 years: | 1.13 male(s)/female (2008 est.) |

| 15-64 years: | 1.06 male(s)/female (2008 est.) |

| Nationality: | |

| nationality: | noun: Chinese adjective: Chinese |

| Major ethnic: | Han Chinese |

| Minor ethnic: | Zhuang, Manchu, Hui, Miao, Uyghurs, Yi, Tujia, Mongols, Tibetan, Buyei, Dong, Yao, Korean, Bai, Hani, Li, Kazak, Dai, She, Lisu, Gelao, Lahu, Dongxiang, Va, Sui, Nakhi, Qiang, Tu, Xibe, Mulao, Kyrgyz, Daur, Jingpo, Salar, Blang, Maonan, Tajik, Pumi, Achang, Nu, Ewenki, Gin, Jino, De'ang, Uzbeks, Russian, Yugur, Bonan, Monba, Oroqen, Derung, Tatars, Hezhen, Lhoba, Gaoshan |

| Language: | |

| Official: | Putonghua (Mandarin Chinese) |

| Spoken: | Wu (Shanghainese), Yue (Cantonese), Minbei (Fuzhou), Minnan (Hokkien or Taiwanese, Teochiu), Xiang, Gan, Hakka and Patuá |

The demographics of the People's Republic of China are characterized by a large population with a relatively small youth cohort, which is partially a result of the People's Republic of China's one-child policy. The population policies implemented in China since 1979 have helped to prevent an extra 400 million births which would have placed the current population near 1.7 billion. Others believe this figure is greatly exaggerated and that the true impact is closer to 50-60 million.[1]

History

Census

The People's Republic of China conducted censuses in 1953, 1964, and 1982. In 1987 the government announced that the fourth national census would take place in 1990 and that there would be one every ten years thereafter. The 1982 census, which reported a total population of 1,008,180,738, is generally accepted as significantly more reliable, accurate, and thorough than the previous two. Various international organizations eagerly assisted the Chinese in conducting the 1982 census, including the United Nations Fund for Population Activities which donated US$15.6 million for the preparation and execution of the census.

China has been the world's most populous nation for many centuries. When China took its first post-1949 census in 1953, the population stood at 582 million; by the fifth census in 2000, the population had more than doubled, reaching 1.2 billion.

Beginning in the mid-1950s, the Chinese government introduced, with varying degrees of success, a number of family planning, or population control, campaigns and programs. China’s fast-growing population was a major policy matter for its leaders in the mid-twentieth century, so that in the early 1970s, the government implemented the stringent one-child policy (publicly announced in 1979). Under this policy, which had different guidelines for national minorities, married couples were officially permitted only one child. As a result of the policy, China successfully achieved its goal of a more stable and much-reduced fertility rate; in 1971 women had an average of 5.4 children versus an estimated 1.7 children in 2004. Enforcement of the program, however, varied considerably from place to place, depending on the vigilance of local population control workers.

In 1982 China conducted its first population census since 1964. It was by far the most thorough and accurate census taken since 1949 and confirmed that China was a nation of more than 1 billion people, or about one-fifth of the world's population. The census provided demographers with a set of data on China's age-sex structure, fertility and mortality rates, and population density and distribution. Information was also gathered on minority ethnic groups, urban population, and marital status. For the first time since the People's Republic of China was founded, demographers had reliable information on the size and composition of the Chinese work force. The nation began preparing for the 1982 census in late 1976. Chinese census workers were sent to the United States and Japan to study modern census-taking techniques and automation. Computers were installed in every provincial-level unit except Xizang and were connected to a central processing system in the Beijing headquarters of the State Statistical Bureau. Pretests and smallscale trial runs were conducted and checked for accuracy between 1980 and 1981 in twenty-four provincial-level units. Census stations were opened in rural production brigades and urban neighborhoods. Beginning 1 July 1982, each household sent a representative to a census station to be enumerated. The census required about a month to complete and employed approximately 5 million census takers.

The 1982 census collected data in nineteen demographic categories relating to individuals and households. The thirteen areas concerning individuals were name, relationship to head of household, sex, age, nationality, registration status, educational level, profession, occupation, status of nonworking persons, marital status, number of children born and still living, and number of births in 1981. The six items pertaining to households were type (domestic or collective), serial number, number of persons, number of births in 1981, number of deaths in 1981, and number of registered persons absent for more than one year. Information was gathered in a number of important areas for which previous data were either extremely inaccurate or simply nonexistent, including fertility, marital status, urban population, minority ethnic groups, sex composition, age distribution, and employment and unemployment.

A fundamental anomaly in the 1982 statistics was noted by some Western analysts. They pointed out that although the birth and death rates recorded by the census and those recorded through the household registration system were different, the two systems arrived at similar population totals. The discrepancies in the vital rates were the result of the underreporting of both births and deaths to the authorities under the registration system; families would not report some births because of the one-child policy and would not report some deaths so as to hold on to the rations of the deceased.

Chinese and foreign demographers used the 1982 census age-sex structure as the base population for forecasting and making assumptions about future fertility trends. The data on age-specific fertility and mortality rates provided the necessary base-line information for making population projections. The census data also were useful for estimating future manpower potential, consumer needs, and utility, energy, and health-service requirements. The sudden abundance of demographic data also helped population specialists estimate world population growth.

Fertility and mortality

In 1949 crude death rates were probably higher than 30 per 1,000, and the average life expectancy was only 32 years. Beginning in the early 1950s, mortality steadily declined; it continued to decline through 1978 and remained relatively constant through 1987. One major fluctuation was reported in a computer reconstruction of China's population trends from 1953 to 1987 produced by the United States Bureau of the Census. The computer model showed that the crude death rate increased dramatically during the famine years associated with the Great Leap Forward (1958-60).

According to Chinese government statistics, the crude birth rate followed five distinct patterns from 1949 to 1982. It remained stable from 1949 to 1954, varied widely from 1955 to 1965, experienced fluctuations between 1966 and 1969, dropped sharply in the late 1970s, and increased from 1980 to 1981. Between 1970 and 1980, the crude birth rate dropped from 36.9 per 1,000 to 17.6 per 1,000. The government attributed this dramatic decline in fertility to the wan xi shao (later marriages, longer intervals between births, and fewer children) birth control campaign. However, elements of socioeconomic change, such as increased employment of women in both urban and rural areas and reduced infant mortality (a greater percentage of surviving children would tend to reduce demand for additional children), may have played some role. The birth rate increased in both 1981 and 1982 to a level of 21 per 1,000, primarily as a result of a marked rise in marriages and first births. The rise was an indication of problems with the one-child policy of 1979. Chinese sources, however, indicated that the birth rate decreased to 17.8 in 1985 and remained relatively constant thereafter.

In urban areas, the housing shortage may have been at least partly responsible for the decreased birth rate. Also, the policy in force during most of the 1960s and the early 1970s of sending large numbers of high school graduates to the countryside deprived cities of a significant proportion of persons of childbearing age and undoubtedly had some effect on birth rates (see Cultural Revolution (1966-76)). Primarily for economic reasons, rural birth rates tended to decline less than urban rates. The right to grow and sell agricultural products for personal profit and the lack of an oldage welfare system were incentives for rural people to produce many children, especially sons, for help in the fields and for support in old age. Because of these conditions, it is unclear to what degree education had been able to erode traditional values favoring large families.

Today, the population continues to grow. There is also a serious gender imbalance. Census data obtained in 2000 revealed that 119 boys were born for every 100 girls, and among China’s "floating population" the ratio was as high as 128:100. These situations led the government in July 2004 to ban selective abortions of female fetuses. It is estimated that this imbalance will rise until 2025–2030 to reach 20% then slowly decrease.[2]

China now has an increasingly aging population; it is projected that 11.8% of the population in 2020 will be 65 years of age and older. Health care has improved dramatically in China since 1949. Major diseases such as cholera, typhoid, and scarlet fever have been brought under control. Life expectancy has more than doubled, and infant mortality has dropped significantly. On the negative side, the incidence of cancer, cerebrovascular disease, and heart disease has increased to the extent that these have become the leading causes of death. Economic reforms initiated in the late 1970s fundamentally altered methods of providing health care; the collective medical care system has been gradually replaced by a more individual-oriented approach.

In Hong Kong, the birth rate of 0.9% is lower than its death rate. Hong Kong's population increases because of immigration from the mainland and a large expatriate population comprising about 4%. Like Hong Kong, Macau also has a low birth rate relying on immigration to maintain its population.

Statistics

No statistics have been included for areas currently governed by the Republic of China. Unless stated otherwise, statistics refer only to mainland China. (See Demographics of Hong Kong and Demographics of Macau.)

Population

- Mainland only: 1,321,851,888 (2007)

- Hong Kong: 6,994,500 (2006)

- Macau: 503,000 (2006)

- Total: 1,329,349,388 (2007).

- Population rank: 1 (See List of countries by population.)

Population projection

- 2000: 1,264,587,054

- 2010: 1,347,000,000

- 2020: 1,430,000,000

- 2030: 1,461,000,000

- 2040: 1,463,144,780

- 2050: 1,465,224,000

Population density

- National average density: 137.0 persons per km2 (2007)

Urban-rural ratio

- Urban: 42.3% (2007) - 562,000,000

- Rural: 57.7% (2007) - 767,000,000

Age structure

- 0-14 years: 20.4% (male 143,527,634/female 126,607,344) (2007)

- 15-64 years: 71.7% (male 487,079,770/female 460,596,384) (2007)

- 65 years and over: 7.9% (male 49,683,856/female 54,356,900) (2007)

Further breakdown of age distribution

- Under 15: 20.3% (2007)

- 15–29: 22.8% (2007)

- 30–44: 26.7% (2007)

- 45–59: 18.2% (2007)

- 60–74: 9.4% (2007)

- 75–84: 2.3% (2007)

- 85 and over: 0.3% (2007)

Median age

- Total: 33.2 years (2007)

- Male: 32.7 years (2007)

- Female: 33.7 years (2007)

Population growth rate

- Population growth rate: 0.606% (2007)

- Natural increase rate: 6.06/1,000 population (2007)

Birth rate

- Birth rate: 13.45 births/1,000 population (2007)

Death rate

- Death rate: 7 deaths/1,000 population (2007)

Net migration rate

- Net migration rate: -0.39 migrant(s)/1,000 population (2007)

Sex distribution

- Sex distribution: male 51.53%; female 48.47% (2007)

Sex ratio

- At birth: 1.11 male(s)/female (2007)

- Under 15 years: 1.134 male(s)/female (2007)

- 15-64 years: 1.057 male(s)/female (2007)

- 65 years and over: 0.914 male(s)/female (2007)

- Total population: 1.06 male(s)/female (2007)

Infant mortality rate

- Total: 22.12 deaths/1,000 live births (2007)

- Male: 20.01 deaths/1,000 live births (2007)

- Female: 24.47 deaths/1,000 live births (2007)

Child mortality

- 415,000 children (under 16) died in China in 2006 (4.3 percent of the world total)[3]

Life expectancy at birth

- Total population: 72.88 years (2007)

- Male: 71.13 years (2007)

- Female: 74.82 years (2007)

Total fertility rate

- Total fertility rate: 1.75 (avg. births per woman in childbearing years) (2007)

According to the 2000 census, the TFR was 1.22 (0.86 for cities, 1.08 for towns and 1.43 for villages/outposts). Beijing had the lowest TFR at 0.67, while Guizhou had the highest at 2.19. It should be noted that Xiangyang district of Jiamusi city (Heilongjiang) have a TFR of 0.41, which is the lowest TFR recorded anywhere in the world in recorded history. Other extreme low TFR counties are: 0.43 in the Heping district of Tianjin city (Tianjin), and 0.46 in the Mawei district of Fuzhou city (Fujian). At the other end TFR was 3.96 in Geji County (Tibet), 4.07 in Jiali County (Tibet), and 5.47 in Baqing County (Tibet).[4]

Marriage and divorce

- Marriage rate: 6.3/1,000 population (2006)

- Divorce rate: 1.0/1,000 population (2006)

Literacy rate

Age 15 and over can read and write:

- Total population: 90.9% (2000 census)

- Male: 95.1% (2000 census)

- Female: 86.5% (2000 census)

Educational attainment

As of 2000, percentage of population age 15 and over having:

- no schooling and incomplete primary: 15.6%

- completed primary: 35.7%

- some secondary: 34.0%

- complete secondary: 11.1%

- some postsecondary through advanced degree: 3.6%

Religious affiliation

- Predominantly: Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism (Ancestor Worship)

- Minorities: Christianity (3% - 4%), Islam (1.5%), others

- Note: State atheism, but traditionally pragmatic and eclectic

Major cities

Only urban population stated (over 1 million people at least), as of 2005:

- Shanghai 10,030,800

- Beijing 7,699,300

- Tianjin 4,933,100

- Guangzhou 4,653,100

- Wuhan 4,593,400

- Chongqing 4,239,700

- Shenyang 3,995,500

- Nanjing 2,966,000

- Harbin 2,735,100

- Chengdu 2,664,000

- Xi’an 2,657,900

- Jinan 2,346,000

- Changchun 2,283,800

- Dalian 2,181,600

- Hangzhou 2,059,800

- Shijiazhuang 1,971,000

- Taiyuan 1,970,300

- Qingdao 1,930,200

- Zhengzhou 1,770,800

- Kunming 1,597,800

- Lanzhou 1,576,400

- Changsha 1,562,200

- Xiamen 1,532,200.

Households

- Average household size: 3.1

- Total households: 351,233,698

- Of which are family households: 340,491,197 (96.9%)

- Of which are collective households: 10,742,501 (3.1%)

HIV

- See HIV/AIDS in the People's Republic of China.

- Adult population (ages 15–49) living with HIV: 0.1% (2003)

- People living with HIV/AIDS: 840,000 (2003)

- HIV/AIDS deaths: 44,000 (2003)

Causes of death

Major causes of death per 100,000 population, based on 2004 urban population samples:

- malignant neoplasms (cancers): 119.7

- cerebrovascular disease: 88.4

- respiratory diseases: 78.1

- heart diseases: 74.1

- accidents, violence, and poisoning: 43.5

Income

As of 2003, the distribution of urban household income:

- Average per capita disposable income by quintile: Y 9,061 [U.S.$1,095]

- first quintile: Y 3,285

- second quintile: Y 5,377

- third quintile: Y 7,279

- fourth quintile: Y 9,763

- fifth quintile: Y 17,431

Working life

Quality of working life:

- Average workweek: 40 hours (1998)

- Annual rate per 100,000 workers for: (1997)

- injury or accident: 0.7

- industrial illness: 36

- death: 1.4

- Death toll from work accidents: 127,000 (2005)

- Funds for pensions and social welfare relief: Y 26,668,000,000 (2001)

Access to services

- Percentage of population having access to electricity (2000): 98.6%

- Percentage of total population with safe public water supply (2002): 83.6% (urban, rural: 94.0%, 73.0%)

- Sewage system (1999): total (urban, rural)

- households with flush apparatus 20.7% (50.0%, 4.3%)

- with pit latrines 69.3% (33.6%, 86.7%)

- with no latrine 5.3% (7.8%, 4.1%)

Social participation

- Eligible voters participating in last national election: n/a

- Population participating in voluntary work: n/a

- Trade union membership in total labor force (2005): 18%

- Practicing religious population in total affiliated population: n/a

Social deviance

Annual reported arrest rate per 100,000 population (2006) for:

- Property violation: 20.7

- Infringing personal rights: 7.2

- Disruption of social administration: 3.3

- Endangering public security: 1.010

Material wellbeing

Urban households possessing (number per household; 2003):

- bicycles: 1.4

- color televisions: 1.3

- washing machines: 0.9

- refrigerators: 0.9

- cameras: 0.5

Rural families possessing (number per household; 2003):

- bicycles: 1.2

- color televisions: 0.7

- washing machines: 0.2

- refrigerators: 0.1

- cameras: 0.02

Household income and expenditure

- Average household size (2005) 3.1; rural households 3.3; urban households 3.0.

- Average annual per capita disposable income of household (2005): rural households Y 3,255 (U.S.$397), urban households Y 10,493 (U.S.$1,281).

- Sources of income (2003): rural households — income from household businesses 75.7%, wages 19.1%, transfers 3.7%, other 1.5%; urban households — wages 70.7%, transfers 23.3%, business income 4.5%, other 1.5%.

- Expenditure: rural (urban) households — food 45.6% (37.1%), housing 15.9% (10.7%), education and recreation 12.1% (14.4%), transportation and communications 8.4% (11.1%), clothing 5.7% (9.8%), medicine and medical service 6.0% (7.1%), household furnishings 4.2% (6.3%).

Employment

- Population economically active (2003): total 760,800,000.

- Activity rate of total population 58.9% (participation rates: over age 15 [2001] 77.7%; female [2001] 37.8%; registered unemployed in urban areas [December 2004] 4.2%).

- Urban employed workforce (2001): 239,400,000; by sector: state enterprises 76,400,000, collectives 28,130,000, self-employment or privately run enterprises 134,870,000.

- Rural employed workforce: 490,850,000.

Population control

- See also: One-child policy

Initially, China's post-1949 leaders were ideologically disposed to view a large population as an asset. But the liabilities of a large, rapidly growing population soon became apparent. For one year, starting in August 1956, vigorous support was given to the Ministry of Public Health's mass birth control efforts. These efforts, however, had little impact on fertility. After the interval of the Great Leap Forward, Chinese leaders again saw rapid population growth as an obstacle to development, and their interest in birth control revived. In the early 1960s, schemes somewhat more muted than during the first campaign, emphasized the virtues of late marriage. Birth control offices were set up in the central government and some provincial-level governments in 1964. The second campaign was particularly successful in the cities, where the birth rate was cut in half during the 1963-66 period. The upheavel of the Cultural Revolution brought the program to a halt, however.

In 1972 and 1973 the party mobilized its resources for a nationwide birth control campaign administered by a group in the State Council. Committees to oversee birth control activities were established at all administrative levels and in various collective enterprises. This extensive and seemingly effective network covered both the rural and the urban population. In urban areas public security headquarters included population control sections. In rural areas the country's "barefoot doctors" distributed information and contraceptives to people's commune members. By 1973 Mao Zedong was personally identified with the family planning movement, signifying a greater leadership commitment to controlled population growth than ever before. Yet until several years after Mao's death in 1976, the leadership was reluctant to put forth directly the rationale that population control was necessary for economic growth and improved living standards.

Population growth targets were set for both administrative units and individual families. In the mid-1970s the maximum recommended family size was two children in cities and three or four in the country. Since 1979 the government has advocated a one-child limit for both rural and urban areas and has generally set a maximum of two children in special circumstances. As of 1986 the policy for minority nationalities was two children per couple, three in special circumstances, and no limit for ethnic groups with very small populations. The overall goal of the one-child policy was to keep the total population within 1.2 billion through the year 2000, on the premise that the Four Modernizations program would be of little value if population growth was not brought under control.

The one-child policy was a highly ambitious population control program. Like previous programs of the 1960s and 1970s, the one-child policy employed a combination of public education, social pressure, and in some cases coercion. The one-child policy was unique, however, in that it linked reproduction with economic cost or benefit.

Under the one-child program, a sophisticated system rewarded those who observed the policy and penalized those who did not. Couples with only one child were given a "one-child certificate" entitling them to such benefits as cash bonuses, longer maternity leave, better child care, and preferential housing assignments. In return, they were required to pledge that they would not have more children. In the countryside, there was great pressure to adhere to the one-child limit. Because the rural population accounted for approximately 60 percent of the total, the effectiveness of the one-child policy in rural areas was considered the key to the success or failure of the program as a whole.

In rural areas the day-to-day work of family planning was done by cadres at the team and brigade levels who were responsible for women's affairs and by health workers. The women's team leader made regular household visits to keep track of the status of each family under her jurisdiction and collected information on which women were using contraceptives, the methods used, and which had become pregnant. She then reported to the brigade women's leader, who documented the information and took it to a monthly meeting of the commune birth-planning committee. According to reports, ceilings or quotas had to be adhered to; to satisfy these cutoffs, unmarried young people were persuaded to postpone marriage, couples without children were advised to "wait their turn," women with unauthorized pregnancies were pressured to have abortions, and those who already had children were urged to use contraception or undergo sterilization. Couples with more than one child were exhorted to be sterilized.

The one-child policy enjoyed much greater success in urban than in rural areas. Even without state intervention, there were compelling reasons for urban couples to limit the family to a single child. Raising a child required a significant portion of family income, and in the cities a child did not become an economic asset until he or she entered the work force at age sixteen. Couples with only one child were given preferential treatment in housing allocation. In addition, because city dwellers who were employed in state enterprises received pensions after retirement, the sex of their first child was less important to them than it was to those in rural areas.

Numerous reports surfaced of coercive measures used to achieve the desired results of the one-child policy. The alleged methods ranged from intense psychological pressure to the use of physical force, including some grisly accounts of forced abortions and infanticide. Chinese officials admitted that isolated, uncondoned abuses of the program occurred and that they condemned such acts, but they insisted that the family planning program was administered on a voluntary basis using persuasion and economic measures only. International reaction to the allegations were mixed. The UN Fund for Population Activities and the International Planned Parenthood Association were generally supportive of China's family planning program. The United States Agency for International Development, however, withdrew US$10 million from the Fund in March 1985 based on allegations that coercion had been used.

Observers suggested that an accurate assessment of the one-child program would not be possible until all women who came of childbearing age in the early 1980s passed their fertile years. As of 1987 the one-child program had achieved mixed results. In general, it was very successful in almost all urban areas but less successful in rural areas.

Rapid fertility reduction associated with the one-child policy has potentially negative results. For instance, in the future the elderly might not be able to rely on their children to care for them as they have in the past, leaving the state to assume the expense, which could be considerable. Based on United Nations and Chinese government statistics, it was estimated in 1987 that by the year 2000 the population 60 years and older (the retirement age is 60 in urban areas) would number 127 million, or 10.1 percent of the total population; the projection for 2025 was 234 million elderly, or 16.4 percent. According to projections based on the 1982 census, if the one-child policy were maintained to the year 2000, 25 percent of China's population would be age 65 or older by the year 2040.

Population density and distribution

Overall population density in 1986 was about 109 people per km2. Density was only about one-third that of Japan and less than that of many other countries in Asia and in Europe. The overall figure, however, concealed major regional variations and the high person-land ratio in densely populated areas. In the 11 provinces, special municipalities, and autonomous regions along the southeast coast, population density was 320.6 people per km2.

In 1986 about 94 percent of the population lived on approximately 36 percent of the land. Broadly speaking, the population was concentrated in China Proper, east of the mountains and south of the Great Wall. The most densely populated areas included the Yangtze River Valley (of which the delta region was the most populous), Sichuan Basin, North China Plain, Pearl River Delta, and the industrial area around the city of Shenyang in the northeast. Population is most sparse in the mountainous, desert, and grassland regions of the northwest and southwest. In Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, portions are completely uninhabited, and only a few sections have populations denser than ten people per km2. The Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Xizang autonomous regions and Gansu and Qinghai provinces comprise 55 percent of the country's land area but in 1985 contained only 5.7 percent of its population.

While China is the most populated country in the world, its national population density (137/km2) is not so high, similar to those of Switzerland and the Czech Republic. The vast majority of China's population lives in the fertile plains of the east, whereas the western half of the country is very large and relatively unpopulated.

Future challenges for China will be the gender disparity partially caused by the preference for boys under the 'one-child' system, and the aging of the population, with an increasing problem of young-old disparity. The latter is likely to be tied to the former, as the lack of sufficient female partners for males coming of age is expected to reduce total births.

Migration

Urbanization

Ethnic groups

The People's Republic of China (PRC) officially recognizes 56 distinct ethnic groups, the largest of which are Han, who constitute about 91.9% of the total population. Ethnic minorities constitute 8.1% or 107.1 million of China's population. Large ethnic minorities include the Zhuang (16 million or 1.30%), Manchu (10 million or 0.86%), Uyghur (9 million or 0.79%), Hui (9 million or 0.79%), Miao (8 million or 0.72%), Yi (7 million or 0.65%), Tujia (5.75 million or 0.62%), Mongols (5 million or 0.47%), Tibetan (5 million or 0.44%), Buyi (3 million or 0.26%), and Korean (2 million or 0.15%).

Ethnic minorities currently experience higher growth rates than the majority Han population. Their proportion of the population in China has grown from 6.1% in 1953, to 8.04% in 1990, 8.41% in 2000 and 9.44% in 2005. Recent surveys indicate that the population growth rate for ethnic minorities is about 7 times greater than that for the Han population.[11]

Neither Hong Kong nor Macau recognizes the official ethnic classifications maintained by the central government. In Macau the largest substantial ethnic groups of non-Chinese descent are the Macanese, of mixed Chinese and Portuguese descent, as well as migrants from the Philippines and Thailand. Overseas Filipinas working as domestic workers comprise the largest non-Chinese ethnic group in Hong Kong.

Languages

The official spoken standard in the People's Republic of China is Putonghua. Its pronunciation is based on the Beijing dialect of Mandarin

Other languages and dialects include other Mandarin dialects, and Wu (Shanghainese), Yue (Cantonese), Minbei (Fuzhou), Minnan (Hokkien or Taiwanese, Teochiu), Xiang, Gan and Hakka, as well as languages of the minorities.

The seven major mutually unintelligible Chinese dialects which are considered by some to be different languages of the Chinese language family, and by some others to be dialects of the Chinese language. Each of these dialects has many sub-dialects. Over 70% of the Han ethnic group are native speakers of the Mandarin group of dialects spoken in northern and southwestern China. The rest, concentrated in south and southeast China, speak one of the six other major Chinese dialects. In addition to the local dialect, nearly all also speak Standard Chinese or Mandarin (Putonghua) which pronunciation is based on the Beijing dialect, which inself is one of the Mandarin group of dialects, and is the language of instruction in all schools and is used for formal and official purposes. Non-Chinese languages spoken widely by ethnic minorities include Mongolian, Tibetan, Uyghur and other Turkic languages (in Xinjiang), Korean (in the northeast), and Vietnamese (in the southeast).

In addition to Chinese, in the special administrative regions, English is an official language of Hong Kong and Portuguese is an official language of Macau. Patuá is a Portuguese creole spoken by a small number of Macanese. English, though not official, is widely used in Macau. In both of the special administrative regions, the dominant spoken form of Chinese is Cantonese.

For written Chinese, the PRC officially uses simplified Chinese characters in mainland China, while traditional Chinese characters are used in Hong Kong and Macau.

The de-facto spoken standard in Hong Kong and Macao is Yue (Cantonese), although officially it is the Chinese language, not specifying, which spoken form is standard. The written official standard in Hong Kong and Macao is in Standard Mandarin in traditional Chinese characters.

On 1 January 1979, the PRC Government officially adopted the hanyu pinyin system for spelling Chinese names and places in mainland china in Roman letters. A system of romanization invented by the Chinese, pinyin has long been widely used in mainland China on street and commercial signs as well as in elementary Chinese textbooks as an aid in learning Chinese characters. Variations of pinyin also are used as the written forms of several minority languages.

Pinyin replaced other conventional spellings in mainland China's English-language publications. The U.S. Government and United Nations also adopted the pinyin system for all names of people and places in mainland China. For example, the capital of the PRC is spelled "Beijing" rather than "Peking".

Religions

The Chinese Communist Government has implemented state atheism since 1949, which makes it difficult to ascertain data on the religious population figures. Thus making the relation between Government and religions was not smooth in the past. But in fact, the people are still holding private worship of traditional religions (Buddhism/Taoism) at home.[10][12] In recent years, the Chinese government has opened up to religion, especially traditional religions such as Mahayana Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism because the Government also continued to emphasize the role of religion in building a "Harmonious Society," which was a positive development with regard to the Government's respect for religious freedom.[13]

According to the old Chinese government estimate, there were "over 100 million followers of various faiths" in China[14]. Other estimates put about 100 million or about 8% Chinese who follow Buddhism, with the second largest religion as Taoism (no data), Islam (19 million or 1.5%) and Christianity (14 million or 1%; 4 million Roman Catholics and 10 million Protestants).[15] According to the 1993 edition of The Atlas of Religion, the number of atheists in China is between 10 and 14 percent.[16]

Additionally, the BBC reported in February 2007 that "a poll of 4,500 people by Shanghai university professors found 31.4% of people above the age of 16 considered themselves as religious", a figure that represents 300 million people[17]. Among those surveyed, about 2/3 were "Buddhists, Taoists or worshipers of legendary figures such as the Dragon King and God of Fortune." Other religions represented significantly in that survey were Christianity (40 million) and Islam. China is also known to have small numbers of people who follow Hinduism, Dongbaism, Bon and a number of new religions and sects (particularly Xiantianism and Falun Gong). The official China Daily called the Shanghai professors' research "the country's first major survey on religious beliefs".[18] The Chinese government have accepted these new numbers. The wide disparity among these estimates underscores the difficulty of accurately surveying the religious view of a nation of over a billion people and the lack of reliable data.

However, some surveys suggest that the cultural adherents or even outright religious adherents of Buddhism could number as high as 50% to 80% of the population, or about 660 million to over 1 billion[19][20]. Some estimates for Taoism as high as 400 million or about 30% of the total population,[21] but Adherents.com argues that these are actually numbers for Chinese folk religion or Chinese traditional religion, not Confucianism and Taoism themselves.[22]

The number of adherents to these religions can be overlaid in percentage due to the fact that mostly Chinese consider themselves both Buddhist and Taoist.[23][24][25][26] However, it was difficult to estimate accurately the number of Buddhists because they did not have congregational memberships and often did not participate in public ceremonies.[27]

The minority religions are Christianity (between 40 million, 3%,[17] and 54 million, 4%[28]), Islam (20 million, 1.5%), Hinduism, Dongbaism, Bon and a number of new religions and sects (particularly Xiantianism and Falun Gong).

According to the surveys of Phil Zuckerman on Adherents.com; in 1993, 59% (over 700 million)[29] of the Chinese population was irreligious but in the newest survey (same author) in 2005, it was only 14% (over 180 million).[30].[31] There are intrinsic logistical difficulties in trying to count the number of religious people anywhere, as well as difficulties peculiar to China. According to Phil Zuckerman, "low response rates," "non-random samples," and "adverse political/cultural climates" are all persistent problems in establishing accurate numbers of religious believers in a given locality.[32] Similar difficulties arise in attempting to subdivide religious people into sects. These issues are especially pertinent in China for two reasons. First, it is a matter of current debate whether several important belief systems in China constitute "religions." As Daniel L. Overmeyer writes, in recent years there has been a "new appreciation...of the religious dimensions of Confucianism, both in its ritual activities and in the inward search for an ultimate source of moral order".[33] Many Chinese belief systems have concepts of a sacred and sometimes spiritual natural world yet do not always invoke a concept of personal god (with the exception of Heaven worship).[34]

The constitution affirms religious toleration subject to several important restrictions. The government places limits on religious practice outside officially recognized organizations. Only two Christian organizations, a Catholic church without ties to the Holy See in Rome and the "Three-Self-Patriotic" Protestant church, are sanctioned by the PRC Government. Unauthorized churches have sprung up in many parts of the country, and unofficial religious practice is flourishing. In some regions authorities have tried to control activities of these unregistered churches. In other regions registered and unregistered groups are treated similarly by authorities, and congregates worship in both types of churches. On 20 July 1999, the Chinese authorities banned[35] and initiated a crackdown[36] on Falun Gong in mainland China.

The Basic Law of Hong Kong protects freedom of religion as a fundamental right. There are a large variety of religious groups in the Hong Kong: Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, Christianity including Catholicism, Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism and Judaism all have a considerable number of adherents.

The Macau Basic Law similarly recognizes freedom of religion though the Religious Freedom Ordinance requires registration of religious organizations. The major religions practiced in Macau are Buddhism and traditional beliefs with a smaller minority claiming no religious belief. A small minority of Christians, mostly Catholic, exists.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Pascal Rocha da Silva, La politique de l'enfant unique en République populaire de Chine, p. 116, cf.

- ↑ Pascal Rocha da Silva, Projection de la population chinoise 2000-2050, p. 9, cf.

- ↑ Taipei Times - archives

- ↑ FERTILITY IN CHINA IN 2000: A COUNTY LEVEL ANALYSIS

- ↑ CIA Factbook - China

- ↑ Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs - Background Note: China

- ↑ Chinese Religions

- ↑ Travel China Guide

- ↑ Han Chinese people

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 China - Religion

- ↑ Communiqué on Major Data of 1% National Population Sample Survey in 2005

- ↑ CIA - The World Factbook: China

- ↑ U.S. Department of States: International Religious Freedom Report 2007 - China (includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau)

- ↑ Religious beliefs

- ↑ China in Brief - china.org.cn

- ↑ O'Brien, Joanne, and Palmer, Martin. "The Atlas of Religion". University of California Press (Berkely, 1993) in Zuckerman, pg. 53

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 BBC NEWS | Asia-Pacific | Survey finds 300m China believers

- ↑ "Religious Believers Thrice The Official Estimate Poll". China Daily, 7 February 2007. Chinadaily.com.cn

- ↑ Buddhists in the world

- ↑ SEANET Work - "Counting the Buddhist World Fairly," by Dr. Alex Smith

- ↑ [http://asiasentinel.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=468&Itemid=34 Asia Sentinel - How Now Tao?

- ↑ Adherents.com - Major Religions Ranked by Size

- ↑ Religions and Beliefs in China

- ↑ SACU Religion in China

- ↑ Index-China Chinese Philosophies and religions

- ↑ The Diaspora Han Chinese

- ↑ U.S. Department of States - International Religious Freedom Report 2006: China (includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau)

- ↑ China Survey Reveals Fewer Christians than Some Evangelicals Want to Believe

- ↑ Adherents.com

- ↑ Adherents.com

- ↑ Top 50 Countries With Highest Proportion of Atheists / Agnostics (Zuckerman, 2005)

- ↑ Zuckerman, Phil. "Atheism: Contemporary Numbers and Patterns". In Martin, Michael "The Cambridge Companion to Atheism". (New York: Cambridge University Press) 2006. pg. 47

- ↑ Overmeyer, Daniel L. et al. "Introduction". The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 54, No. 2 (May, 1995). pp. 314-321

- ↑ Ethel R. Nelson, Richard E. Broadberry, and Ginger Tong Chock. God's Promise to the Chinese. p 8. ISBN 0-937869-01-5.

- ↑ Xinhua, China Bans Falun Gong, People's Daily, 22 July 1999

- ↑ "The crackdown on Falun Gong and other so-called "heretical organizations"". Amnesty International (2000-03-23). Retrieved on 2007-08-16.

This article contains material from the Library of Congress Country Studies, which are United States government publications in the public domain. [1]

References

- China Statistical Information Net

- Chinese Embassy in the United States

- China, CIA World Factbook

- Population by Age and Sex, 1950 - 2050; Proportion Elderly, Working Age, and Children at China-Profile

- Literacy rate in China at Pinyin news

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||