Deck (ship)

A deck is a permanent covering over a compartment or a hull[1] of a ship. On a boat or ship, the primary deck is the horizontal structure which forms the 'roof' for the hull, which both strengthens the hull and serves as the primary working surface. Vessels often have more than one level both within the hull and in the superstructure above the primary deck which are similar to the floors of a multi-story building, and which are also referred to as decks, as are specific compartments and decks built over specific areas of the superstructure. (Decks for some purposes have specific names; see below.)

Contents |

Discussion

The purpose of the primary deck is structural, and only secondarily to provide weather-tightness, and to support people and equipment. The deck serves as the lid to the complex box girder which is the hull. It resists tension, compression, and racking forces. The deck's scantling is usually the same as the topsides, or might be heavier if the deck is expected to carry heavier loads (for example a container ship). The deck will be reinforced around deck fittings such as the capstan, cleats, or bollards.

On ships with more than one level, deck refers to the level itself. The actual floor surface is called the sole, while the term floor refers to a structural member tying the ships frames or ribs together over the keel. In modern ships, the interior decks are usually numbered from the primary deck, which is #1, downward and upward. So the first deck below the primary deck will be #2, and the first above the primary deck will be #A2 or #S2 (for "Above" or "Superstructure"). However, ships may also call decks by common names, or (especially on cruise ships) may invent fanciful and romantic names for a specific deck or area of that specific ship, such as the Lido deck of the Princess Cruises' Love Boat.

Equipment mounted on deck, such as the ship's wheel, binnacle, fife rails, and so forth, may be collectively referred to as deck furniture. Weather decks in western designs evolved from having structures fore and aft (forecastles and cabins) to mostly clear, then in the 19th century pilothouses and deckhouses began to appear, eventually developing into the superstructure of modern ships. Eastern designs developed earlier, with efficient middle decks and minimalist fore and aft cabin structures across a range of designs.

Common names for decks

In vessels having more than one deck there are various naming conventions, numerically, alphabetically, etc. However, there are also a variety of common historical names and types of decks:

- Berth deck: (Naval) A deck next below the gun deck, where the hammocks of the crew are swung.

- Boat deck: Especially on ships with sponsons, the deck area where lifeboats or the ship's gig are stored.

- Boiler deck: (River Steamers) The deck on which the boilers are placed.

- Bridge deck: (a) The deck area including the helm and navigation station, and where the Officer of the Deck will be found, also known as the conn (b) An athwartships structure at the forward end of the cockpit with a deck, often somewhat lower than the primary deck, to prevent a pooping wave from entering through the companionway.

- Flight deck: (Naval) A deck from which aircraft take off or land.

- Flush deck: Any continuous, unbroken deck from stem to stern.

- Gun deck: (Naval) a deck below the spar deck, on which the ship's guns are carried. If there are two gun decks, the upper one is called the main deck, the lower, the lower gun deck; if there are three, one is called the middle gun deck.

- Half-deck: That portion of the deck next below the spar deck which is between the mainmast and the cabin.

- Helo deck: Usually located near the stern and always kept clear of obstacles hazardous to a helicopter landing.

- Hurricane deck: (River Steamers, etc.), the upper deck, usually a light deck, erected above the frame of the hull (deriving its name from the wind that always seemed to blow on the deck).[2]

- Main deck: The highest deck of the hull (also called the upper deck, see below), usually but not always the weather deck. Anything above the main deck is superstructure.

- Middle or Waist deck The upper deck amidships, the working area of the deck.

- Orlop deck: The deck or part of a deck where the cables are stowed, usually below the water line. It is the lowest deck in a ship.

- Poop deck: The deck forming the roof of a poop or poop cabin, built on the upper deck and extending from the mizzenmast aft.

- Promenade deck: A "wrap-around porch" found on passenger ships and riverboats encircling the superstructure.

- Quarter-deck: (a) The part of the upper deck abaft the mainmast, including the poop deck when there is one. Usually reserved for ship's officers, guests, and passengers. (b) (Naval) The area to which a gangway for officers and diplomatic guests to board the vessel leads. Also any entry point for personnel.

- Side-deck: The upper deck outboard of any structures such as a coachroof or doghouse, also called a breezeway

- Spar deck: (a) Same as the upper deck. (b) Sometimes a light deck fitted over the upper deck.

- Sweep deck: (Naval) The aftmost deck on a minesweeper, set close to the waterline for ease in launch and recovery of equipment.

- Tween deck: the storage space between the hold and the main deck, often retractable.

- Upper deck: The highest deck of the hull, extending from stem to stern.

- Weather deck: (a) Any deck exposed to the outside. (b) The windward side decks. [3]

- Well deck: (Naval) A hangar like deck located at the water line in the stern of some amphibious assault ships. By taking on water the ship can lower the stern flooding the well deck and allowing boats and amphibious landing craft to dock within the ship.

Construction

Methods in wood

A traditional wood deck would consist of planks laid fore and aft over beams and along carlins, the seams of which are caulked and paid with tar. A yacht or other fancy boat might then have the deck canvased, with the fabric laid down in a thick layer of paint or sealant, and additional coats painted over. The wash or apron boards form the joint between the deck planking and that of the topsides, and are caulked similarly.

Modern "constructed decks" are used primarily on fiberglass, composite, and cold-molded hulls. The under structure of beams and carlins is the same as above. The decking itself is usually multiple layers of marine-grade plywood, covered over with layers of fibreglass in a plastic resin such as epoxy or polyester overlapped onto the topsides of the hull.

Methods in metal

Generally speaking, the method outlined for "constructed decks" is most similar to metal decks. The deck plating is laid over metal beams and carlins and tacked temporarily in place. The difficulty in metal construction is avoiding distortion of the plate while welding due to the high heat involved in the process. Welds are usually double pass, meaning each seam is welded twice, a time consuming process which may take longer than building the wood deck. But welds result in a waterproof deck which is strong and easily repairable. The deck structure is welded to the hull, making it structurally a single unit.

Because a metal deck, painted to reduce corrosion, can be quite slippery as well as picking up heat from the sun and being quite loud to work on, often a layer of wood decking or thick non-skid paint are applied to its surface.

Methods in fibreglass

The process for building a deck in fibreglass is the same as for building a hull: a female mould is built, a layer of gel coat is sprayed in, then layers of fibreglass in resin are built up to the required deck thickness (if the deck has a core, the outer skin layers of fibreglass and resin are laid, then the core material, and finally the inner skin layers.) The deck is removed from the mould and usually mechanically fastened to the hull.

Fibreglass decks are quite slick with their mirror-smooth surfaces, so a non-skid texture is often moulded into their surface, or non-skid pads glued down in working areas.

Rules of thumb to determine the deck scantlings:

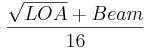

The thickness of the decking affects how strong the hull is, and is directly related to how thick the skin of the hull itself is, which is of course related to how large the vessel is, the kind of work it is expected to do, and the kind of weather it may reasonably be expected to endure. While a Naval Engineer or Architect may have precise methods of determining what the scantlings should be, traditional builders used previous experiences and simpler rules-of-thumb to determine how thick the deck should be built.

The numbers derived by these formulae gives a rough number for determining the average thickness of materials based on some crude hull measurements. Below the waterline the thickness should be approximately 115% of the result, while upper topsides and decks might be reduced to 85% of the result.

- In wood – For plank thickness in inches, LOA (Length OverAll) and Beam are measured in feet. For plank thickness in mm, LOA and Beam are measured in meters.

- Plank thickness in inches =

- Plank thickness in mm =

![[\sqrt{LOA*3.28}+(Beam*3.28)*1.58]](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/653a64800dc267b4af23f1d7e771583d.png)

- Plank thickness in inches =

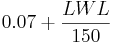

- In fiberglass – For skin thickness in inches, LWL (Length WaterLine) is in feet. For skin thickness in mm, LWL is in meters.

- Skin thickness (inches) =

- Skin thickness (mm) =

- Skin thickness (inches) =

- In fiberglass sandwich – First determine the skin thickness as single skin, then multiply by modifiers for inner skin, outer skin, and core thicknesses. Cored decks might be modified even thicker, 2.6–2.7, to increase stiffness.

- Inner skin modifier = 0.3

- Outer skin modifier = 0.4

- Core modifier = 2.2

Glossary

A brief glossary, by no means complete.

- athwartships – perpendicular to fore and aft.

- beam – a timber similar in use to a floor joist, which runs from one side of the hull to the other athwartships.

- boat – A smaller vessel able to be carried on the deck of a larger one.

- carlin – similar to a beam, except running in a fore and aft direction.

- caulk – to make water-tight by driving caulking (usually loose cotton fibers) into a seam, followed by a coarser fiber material such as oakum.

- core – in fibreglass construction, a layer between fiberglass skins, made of foam, end grain balsa, or other strengthening material to increase the stiffness of the deck.

- fore and aft – parallel to a line from the stem to the stern.

- gel coat – a heavily pigmented layer of plastic resin.

- oakum – loosely twisted hemp or jute or other crude fibre, sometimes treated with creosote or tar before use.

- pay – to pour into or fill up a seam so it is level with the top of the plank.

- plating – sheets of metal, generally simple flat pieces but may be formed into complex curvatures.

- pooping wave – A wave which comes over the stern and onto the deck.

- scantling – the critical dimensions of any element of the ship; so for the skin and deck of the hull it would be the thickness (of the planks, fibreglass layup, hull plating, etc.)

- seam – the space between two planks.

- ship – There are several definitions of ship, but in this case it is a vessel large enough to carry boats on deck. Seamen say it succinctly – ships carry boats.

- stem – The timber at the front of the hull.

- stern – back end of the hull

- topsides – the upper surfaces of the hull from the waterline to the deck.

References

- ↑ Edwards, Fred (illustrated by Sollers, Jim); Sailing as a Second Language: An illustrated dictionary; International Marine Publishing Company; © 1988 Highmark Publishing Ltd.; ISBN 0-87742-965-0

- ↑ Hurricane Deck

- ↑ Webster, Noah Ed.; Webster's Unabridged Dictionary – 1913; Project Gutenberg(eText numbers 660–670)

- ↑ Gerr, David; The Nature of Boats: Insights and esoterica for the nautically obsessed; International Marine; © 1992 International Marine; ISBN 0-87742-289-3

Anatomy of sailing ships

|

|||||