Debit card

A debit card (also known as a bank card) is a plastic card which provides an alternative payment method to cash when making purchases. Functionally, it can be called an electronic check, as the funds are withdrawn directly from either the bank account (often referred to as a check card), or from the remaining balance on the card. In some cases, the cards are designed exclusively for use on the Internet, and so there is no physical card.[1][2]

The use of debit cards has become widespread in many countries and has overtaken the cheque, and in some instances cash transactions by volume. Like credit cards, debit cards are used widely for telephone and Internet purchases.

Debit cards can also allow for instant withdrawal of cash, acting as the ATM card for withdrawing cash and as a cheque guarantee card. Merchants can also offer "cashback"/"cashout" facilities to customers, where a customer can withdraw cash along with their purchase.

Contents |

Credit or Debit?

For consumers, the difference between a "debit card" and a "credit card" is that the debit card deducts the balance from a deposit account, like a checking account, whereas the credit card allows the consumer to spend money on credit to the issuing bank. In other words, a debit card uses the money you have and a credit card uses the money you don't.

In some countries: When a merchant asks "credit or debit?" the answer determines whether they will use a merchant account affiliated with one or more traditional credit card associations (Visa, MasterCard, Discover, or American Express) or an interbank network typically used for debit and ATM cards, like Plus, Pulse, Cirrus, or Maestro.

In other countries: When a merchant asks "credit or debit?" the answer determines whether the transaction will be handled as a credit transaction or as a debit transaction. In the former case, the merchant is more likely than in the latter case to have to pay a fee defined by fixed percentage to the merchant's bank. In both cases, the merchant may have to pay a fixed amount to the bank. In either case, the transaction will go through a major credit/debit network (such as Visa, MasterCard, Visa Electron or Maestro). In either case, the transaction may be conducted in either online or offline mode, although the card issuing bank may choose to block transactions made in offline mode. This is always the case with Visa Electron transactions, usually the case with Maestro transactions and rarely the case with Visa or MasterCard transactions.

In yet other countries: A merchant will only ask for "credit or debit?" if the card is a combined credit+debit card. If the payee chooses "credit", the credit balance will be debited the amount of the purchase; if the payee chooses "debit", the bank account balance will be debited the amount of the purchase.

This may be confusing because "debit cards" which are linked directly to a checking account are sometimes dual-purpose, so that they can be used seamlessly in place of a credit card, and can be charged by merchants using the traditional credit networks. There are also "pre-paid credit cards" which act like a debit card but can only be charged using the traditional "credit" networks. The card itself does not necessarily indicate whether it is connected to an existing pile of money, or merely represents a promise to pay later.

In some countries: The "debit" networks typically require that purchases be made in person and that a personal identification number be supplied. The "credit" networks allow cards to be charged with only a signature, and/or picture ID.

In other countries: Identification typically requires the entering of a personal identification number or signing a piece of paper. This is regardless of whether the card network in use mostly is used for credit transactions or for debit transactions. In the event of an offline transaction (regardless of whether the offline transaction is a credit transaction or a debit transaction), identification using a PIN is impossible, so only signatures on pieces of paper work.

In some countries: Consumer protections also vary, depending on the network used. Visa and MasterCard, for instance, prohibit minimum and maximum purchase sizes, surcharges, and arbitrary security procedures on the part of merchants. Merchants are usually charged higher transaction fees for credit transactions, since debit network transactions are less likely to be fraudulent. This may lead them to "steer" customers to debit transactions. Consumers disputing charges may find it easier to do so with a credit card, since the money will not immediately leave their control. Fraudulent charges on a debit card can also cause problems with a checking account because the money is withdrawn immediately and may thus result in an overdraft or bounced checks. In some cases debit card-issuing banks will promptly refund any disputed charges until the matter can be settled, and in some jurisdictions the consumer liability for unauthorized charges is the same for both debit and credit cards.

In other countries: In India and Sweden, the consumer protection is the same regardless of the network used. Some banks set minimum and maximum purchase sizes, mostly for online-only cards. However, this has nothing to do with the card networks, but rather with the bank's judgement of the person's age and credit records. Any fees that the customers have to pay to the bank are the same regardless of whether the transaction is conducted as a credit or as a debit transaction, so there is no advantage for the customers to choose one transaction mode over another. Shops may add surcharges to the price of the goods or services in accordance with laws allowing them to do so. Banks consider the purchases as having been made at the moment when the card was swiped, regardless of when the purchase settlement was made. Regardless of which transaction type was used, the purchase may result in an overdraft because the money is considered to have left the account at the moment of the card swiping.

Types of debit card

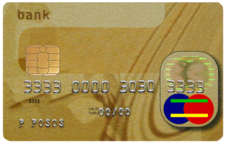

- Issuing bank logo

- EMV chip

- Hologram

- Card number

- Card brand logo

- Expiry date

- Cardholder's name

- Magnetic stripe

- Signature strip

- Card Security Code

Although many debit cards are of the Visa or MasterCard brand, there are many other types of debit card, each accepted only within a particular country or region, for example Switch (now: Maestro) and Solo in the United Kingdom, Carte Bleue in France, Laser in Ireland, "EC electronic cash" (formerly Eurocheque) in Germany and EFTPOS cards in Australia and New Zealand. The need for cross-border compatibility and the advent of the euro recently led to many of these card networks (such as Switzerland's "EC direkt", Austria's "Bankomatkasse" and Switch in the United Kingdom) being re-branded with the internationally recognised Maestro logo, which is part of the MasterCard brand. Some debit cards are dual branded with the logo of the (former) national card as well as Maestro (e.g. EC cards in Germany, Laser cards in Ireland, Switch and Solo in the UK, Pinpas cards in the Netherlands, Bancontact cards in Belgium, etc.). The use of a debit card system allows operators to package their product more effectively while monitoring customer spending. An example of one of these systems is ECS by Embed International. A prepaid debit card looks a lot like a credit card. It even works a lot like a credit card, when you use it in a store to purchase products. However, a prepaid credit card is not a credit card. The two work very differently.

Whenever you use a credit card, you are borrowing money from someone else to purchase something. A credit card is then, in essence, a loan. It doesn’t matter if it is a secure credit card, a small business credit card or anything else: the credit card company is lending you money in order to make your purchase, for which you are going to be charged interest on later (assuming you don’t pay the total balance within a predetermined period).

A prepaid debit card, on the other hand, is not a loan. It is simply a method following some of the principles of credit cards for the basic transaction, but instead of borrowing money from a third party you are taking money straight from your debit card account. This is why it is referred to as prepaid: you put the money into the account, then you can take the money out of it using your debit card, as opposed to paying for the purchase after the fact with a credit card.

Because of this there are no interest rates applied to prepaid debit cards, although there are sometimes fees associated with them. You never have to worry about going into debt using a prepaid debit card, since you are only taking out what you take in. Many people find them a welcome alternative to traditional credit cards. Traditional debit cards, however, are not prepaid but simply linked to a bank account. This means it is sometimes possible to go overdrawn (effectively a loan), and incur interest charges and/or fees. However, if the bank account has sufficient funds to cover the transaction amount, no fees or charges will generally be applied. .

France

Banks in France charge annual fees for debit cards (despite card payments being very cost efficient for the banks), yet they do not charge personal customers for checkbooks or processing checks (despite checks being very costly for the banks). This imbalance most probably dates from the unilateral introduction in France of Chip and PIN debit cards in the early 1990s, when the cost of this technology was much higher than it is now. Credit cards of the type found in the United Kingdom and United States are unusual in France and the closest equivalent is the deferred debit card, which operates like a normal debit card, except that all purchase transactions are postponed until the end of the month, thereby giving the customer between 1 and 31 days of interest-free credit. The annual fee for a deferred debit card is around €10 more than for one with immediate debit. Most France debit cards are branded with the Carte Bleue logo, which assures acceptance throughout France. Most card holders choose to pay around €5 more in their annual fee to additionally have a Visa or a MasterCard logo on their Carte Bleue, so that the card is accepted internationally. A Carte Bleue without a Visa or a MasterCard logo is often known as a "Carte Bleue Nationale" and a Carte Bleue with a Visa or a MasterCard logo is known as a "Carte Bleue Internationale", or more frequently, simply called a "Visa" or "MasterCard". Many smaller merchants in France refuse to accept debit cards for transactions under €15 (equivalent to 100 French Francs) because of the minimum fee charged by merchants' banks per transaction. Merchants in France do not differentiate between debit and credit cards, and so both have equal acceptance. However, Visa's and MasterCard's regulations prohibit merchants from setting minimum charge amounts. American Express's policy is to discourage any merchant practices that create a "barrier to acceptance" and setting minimum charge limits is such a barrier. Amex does prohibit "discrimination" against the Amex card, which means they cannot have minimum charge for Amex but not for Visa and MasterCard but they cannot have a minimum charge for Visa and MasterCard because Visa and MasterCard prohibit this.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, banks started to issue debit cards in the mid 1980s in a bid to reduce the number of cheques being used at the point of sale, which are costly for the banks to process. As in most countries, fees paid by merchants in the United Kingdom to accept credit cards are a percentage of the transaction amount[3], which funds card holders' interest-free credit periods as well as incentive schemes such as points, airmiles or cashback. Debit cards do not usually have these characteristics, and so the fee for merchants to accept debit cards is a low fixed amount, regardless of transaction amount[3]. For very small amounts, this means it is cheaper for a merchant to accept a credit card than a debit card. Although merchants won the right through The Credit Cards (Price Discrimination) Order 1990 to charge customers different prices according to the payment method, few merchants in the UK charge less for payment by debit card than by credit card, the most notable exceptions being budget airlines, travel agents and IKEA[4]. Debit cards in the UK lack the advantages offered to holders of UK-issued credit cards, such as free incentives (points, airmiles, cashback etc), interest-free credit and protection against defaulting merchants under Section 75 of the Consumer Credit Act 1974. Almost all establishments in the United Kingdom that accept credit cards also accept debit cards (although not always Solo and Visa Electron), but a minority of merchants, for cost reasons, accept debit cards and not credit cards (for example the Post Office and, until 1999, John Lewis).

Rest of Europe

Most merchants usually accept debit cards, because the fees for accepting them are much lower than credit card fees, for example in Germany 0.3% with a minimum of €0.08[5] .

In Poland, local debit cards, such as PolCard, have become largely substituted with international ones, such as Visa, MasterCard, or the unembossed Visa Electron or Maestro. Most banks in Poland block Internet and MOTO transactions with unembossed cards, requiring the customer to buy an embossed card or a card for Internet/MOTO transactions only. The number of banks which do not block MOTO transactions on unembossed cards has recently started to increase.

In Hungary debit cards are far more common and popular than credit cards. Many Hungarians even refer to their debit card ("betéti kártya") mistakenly using the word for credit card ("hitelkártya").

US FSA debit cards

In the U.S.A, a FSA debit card only allows medical expenses. It is used by some banks for withdrawals from their FSAs, MSAs, and HSAs as well. They have Visa or MasterCard logos, but cannot be used as "debit cards", only as "credit cards"", and they are not accepted by all merchants that accept debit and credit cards, but only by those that accept FSA debit cards. Merchant codes and product codes are used at the point of sale (required by law by certain merchants by certain dates in the USA) to restrict sales if they do not qualify. Because of the extra checking and documenting that goes on, later, the statement can be used to substantiate these purchases for tax deductions. In the occasional instance that a qualifying purchase is rejected, another form of payment must be used (a check or payment from another account and a claim for reimbursement later). In the more likely case that non-qualifying items are accepted, the consumer is technically still responsible, and the discrepancy could be revealed during an audit.

Online and offline debit transactions

There are currently two ways that debit card transactions are processed: online debit (also known as PIN debit) and offline debit (also known as signature debit). In some countries including the United States and Australia, they are often referred to at point of sale as "debit" and "credit" respectively, even though in either case the user's bank account is debited and no credit is involved.

Some cards are blocked from making either online or offline transactions, while other cards are enabled for both kinds of transactions.

Online debit ("PIN debit" or "debit")

Online debit cards require electronic authorization of every transaction and the debits are reflected in the user’s account immediately. The transaction may be additionally secured with the personal identification number (PIN) authentication system and some online cards require such authentication for every transaction, essentially becoming enhanced automatic teller machine (ATM) cards. One difficulty in using online debit cards is the necessity of an electronic authorization device at the point of sale (POS) and sometimes also a separate PINpad to enter the PIN, although this is becoming commonplace for all card transactions in many countries. Overall, the online debit card is generally viewed as superior to the offline debit card because of its more secure authentication system and live status, which alleviates problems with processing lag on transactions that may have been forgotten or not authorized by the owner of the card. Banks in some countries, such as Canada and Brazil, only issue online debit cards.

In the United States, most online debit transactions are handled by regional ATM networks, though VISA and MasterCard each own online debit networks (Interlink and Maestro, respectively). Online debit is usually provided as a secondary feature on an offline debit card (Visa Check Card or Debit MasterCard); those customers that do not qualify for offline debit cards are often issued ATM cards with online debit capability through the regional ATM, Interlink and/or Maestro networks.

In the United Kingdom, Solo and Visa Electron are examples of online debit cards, which are typically issued by banks to customers whom the bank does not want to go overdrawn under any circumstances, for example under-18s.

In the Philippines, all three national ATM network consortia offer proprietary PIN debit. This was first offered by Express Payment System in 1987, followed by Megalink with Paylink in 1993 then BancNet with the Point-of-Sale in 1994.

Online debit transactions may be conducted either as a debit or a credit transaction. For example, most (all?) Japanese shops allowing debit transaction in online mode will conduct the transaction as a credit transaction.

Online debit with signature

The above section only deals with debit cards in online mode using a PIN code. However, it is very common (at least in Europe) for shops to use a signature as identification for an online transaction. For example, this applies to all shops accepting online-only cards (e.g. Visa Electron and Maestro) while using signatures for identification.

Offline debit ("signature debit" or "credit")

Offline debit cards have the logos of major credit cards (e.g. Visa or MasterCard) or major debit cards (e.g. Maestro in the United Kingdom and other countries, but not the United States) and are used at the point of sale like a credit card. This type of debit card may be subject to a daily limit, and/or a maximum limit equal to the current/checking account balance from which it draws funds. Transactions conducted with offline debit cards require 2–3 days to be reflected on users’ account balances.

In the U.S. and Australia, offline debit transactions are inaccurately referred to as "credit" transactions even though no credit is actually involved. This is because they are processed through the Visa or MasterCard networks in the same manner as actual credit card transactions. Since they are handled like any other Visa or MasterCard, U.S. and Australian offline debit cards are also accepted worldwide at virtually all merchants that accept credit cards of the corresponding brand, even if they do not accept their own country's debit cards.

In the U.S., Visa calls its debit card Visa Check Card; MasterCard calls its debit card Debit MasterCard. The majority of U.S. debit cards are Check Cards.[6] Discover Card has announced an offline debit card through its regional ATM network Pulse; however, few if any banks offer this card. A fourth major U.S. credit card network, American Express, offers prepaid gift cards, which work in a similar fashion.[7]

Some merchants in the U.S. have recently been allowed to bypass the signature requirement for "credit" sales (including offline debit) if the total sale is under a certain dollar amount.[8] This is based on the assumption that customers want a fast point-of-sale process, and low-value transactions are not the activity of a fraudulent user. Some Japanese stores also allow people to pay using a card without signing or entering a PIN code. When using this feature, Sunkus will read the magnetic tape, reserve the money immediately, and settle the transactions in batches up to a month later, while Lawson will read the chip, reserve the money immediately, and settle the transactions individually just a few days later. Some other Japanese convenience store chains also accept card purchases with neither PIN codes nor signatures, as do some Swedish vending machines (payphones, parking meters, bus/train ticket vending machines), either by reading the magnetic tape (ticket vending machines) or by reading the chip (payphones/parking meters).

In the United Kingdom, Maestro (formerly Switch) and Visa Debit (formerly Delta) are examples of offline debit cards.[9] This is in contrast to the U.S. where Maestro is an online debit brand.

In some countries and with some banks and merchant service organizations, a "credit" or offline debit transaction is without cost to the purchaser beyond the face value of the transaction, while a small fee may be charged for a "debit" or online debit transaction (although it is often absorbed by the retailer). Other differences are that online debit purchasers may opt to withdraw cash in addition to the amount of the debit purchase (if the merchant supports that functionality); also, from the merchant's standpoint, the merchant pays lower fees on online debit transaction as compared to "credit" (offline) debit transactions.

The fees charged to merchants on offline debit purchases—and the lack of fees charged merchants for processing online debit purchases and paper checks—have prompted some major merchants in the U.S. to file lawsuits against debit-card transaction processors such as Visa and MasterCard. In 2003, Visa and MasterCard agreed to settle the largest of these lawsuits and agreed to settlements of billions of dollars.

Many consumers prefer "credit" transactions because of the lack of a fee charged to the consumer/purchaser; also, a few debit cards in the U.S. offer rewards for using "credit" (e.g. Washington Mutual's "Wamoola"). However, since "credit" costs more for merchants, many terminals at PIN-accepting merchant locations now make the "credit" function more difficult to access. For example, if you swipe a debit card at Wal-Mart in the U.S., you are immediately presented with the PIN screen for online debit; to use offline debit you must press "cancel" to exit the PIN screen, then press "credit" on the next screen.

One additional problem surrounding the use of debit cards is their use at a self-service gas pump like those common in the U.S. The customer might want to purchase fuel on their debit card, but the pump's computer does not know how much fuel the customer wants. The pump is activated by the customer presenting their card to a card reader (see methods described above) and possibly entering a PIN. At this point the pump will dispense fuel, though no sales transaction has completed. The pump has no way of knowing how much fuel will be sold, nor how much money is available in the customer’s debit account. In a typical sale transaction, trying to spend more money than is available in your account (credit or debit) will result in a "no-sale" alert to the merchant, and the sale does not occur. At a self-serve fuel pump, the fuel is already in the customer's tank by the time the bank knows the final sale price. Several solutions to this problem are in place, such as denying $1 pre-authorizations when an account holds less than $10 while still allowing transactions for specific amounts, but the concept of delivering the merchandise before the sales transaction plagues the debit card system. The commission is sometimes so high that the gas station sometimes actually loses money when someone pays for gas with credit. When pay at the pump started in the 1980s, many gas stations offered a discount for paying with cash. Most of them stopped doing that because the discount did not significantly increase their cash sales.

Offline debit with PIN code

A PIN code is sometimes used for identification in offline mode, at least if the card's chip is read. Some banks also use this system for small devices used together with the banks' Internet services, as a kind of verification that you really are the true account holder.[7] If the code entered is wrong, the device will be able to tell this, despite the device not being connected to any computer network.

Internet purchases

Debit cards may also be used on the Internet. Internet transactions may be conducted in either online or offline mode, although shops accepting online-only cards are rare in some countries (such as Sweden), while they are common in other countries (such as the Netherlands). For a comparison, PayPal offers the customer to use an online-only Maestro card if the customer enters a Dutch address of residence, but not if the same customer enters a Swedish address of residence.

Internet purchases may be conducted in either online or offline mode, and just as in the case where you use your card in a shop, it is (at least in most countries) impossible to tell whether the transaction was conducted in online or offline mode (unless an online-only card was used, in which case you know that it was conducted in online mode), since the mode isn't mentioned on any receipt or similar. Internet purchases use neither a PIN code nor a signature for identification. Transactions may be conducted in either credit or debit mode (which is sometimes, but not always, indicated on the receipt), and this has nothing to do with whether the transaction was conducted on online or offline mode, since both credit and debit transactions may be conducted in both modes.

Issues with deferred posting of offline debit

To the consumer, a debit transaction is perceived as occurring in real-time; i.e. the money is withdrawn from their account immediately following the authorization request from the merchant, which in many countries, is the case when making an online debit purchase. However, when a purchase is made using the "credit" (offline debit) option, the transaction merely places an authorization hold on the customer's account; funds are not actually withdrawn until the transaction is reconciled and hard-posted to the customer's account, usually a few days later. However, the previous sentence applies to all kinds of transaction types, at least when using a card issued by a European bank. This is in contrast to a typical credit card transaction; though it can also have a lag time of a few days before the transaction is posted to the account, it can be many days to a month or more before the consumer makes repayment with actual money.

Because of this, in the case of a benign or malicious error by the merchant or bank, a debit transaction may cause more serious problems (e.g. money not accessible; overdrawn account) than in the case of a credit card transaction (e.g. credit not accessible; over credit limit). This is especially true in the United States, where writing "hot checks" is a crime in every state, but exceeding your credit limit is not.

Cards for mail, telephone and Internet use only

Special pre-paid Visa cards for Mail Order/Telephone Order (MOTO) and Internet use only are made available by a small number of banks. They are sometimes called "virtual Visa cards", although they usually do exist in the form of plastic. An example is 3V. Recently, these virtual cards have been increasingly issued by non-financial institutions such as grocery and convenience stores to consumers as a replacement for money orders (such as PaidByCash in the United States). Such cards can be used whenever the remote store accepts Visa cards. Before making the transaction, the customer transfers the required amount of money from his main account to the card's sub-account using the bank's website or the telephone. Next, the customer gives the card number and the CVV2 code to the merchant, who authorizes the transaction electronically, as with a regular Visa card. If there is enough money on the sub-account, the bank grants the authorization and locks the adequate amount on the sub-account.

Such a card prevents fraud by a card number thief even if the card is not blocked, because the customer normally does not store any money on the sub-account and fraudulent transactions do not get authorized by the bank. For extra security, the CVV2 code is not printed on the card but rather sent separately to the customer in a secured envelope.

The bank also rejects local transactions, that is ones that are not made over the Internet, mail or telephone. However, some merchants use software incompatible with Visa regulations and send authorization requests that wrongly tell the bank that the transaction is not a MOTO/Internet one, in which case the bank rejects the request. Additionally, some merchants do not use electronic authorization at all, in which case the transaction cannot be completed as well. For these two reasons the card is unusable with a small minority of Internet, telephone and postal stores.

Financial access

Debit cards and secured credit cards are popular among college students who have not yet established a credit history. Debit cards may also be used by expatriated workers to send money home to their families holding an affiliated debit card.

Debit cards around the world

In some countries, banks tend to levy a small fee for each debit card transaction. In some countries (e.g. the UK) the merchants bear all the costs and customers are not charged. There are many people who routinely use debit cards for all transactions, no matter how small. Some (small) retailers refuse to accept debit cards for small transactions, where paying the transaction fee would absorb the profit margin on the sale, making the transaction uneconomic for the retailer.

Australia

Debit cards in Australia are called different names depending on the issuing bank: Commonwealth Bank of Australia: Keycard; Westpac Banking Corporation: Handycard; National Australia Bank: FlexiCard; ANZ Bank: Access card; Bendigo Bank: Cashcard.

EFTPOS is very popular in Australia and has been operating there since the 1980s. EFTPOS-enabled cards are accepted at almost all swipe terminals able to accept credit cards, regardless of the bank that issued the card, including Maestro cards issued by foreign banks, with most businesses accepting them, with 450,000 Point Of Sale terminals.[10]

EFTPOS cards can also be used to deposit and withdraw cash over the counter at Australia Post outlets participating in giroPost, just as if the transaction was conducted at a bank branch, even if the bank branch is closed. Electronic transactions in Australia are generally processed via the Telstra Argent and Optus Transact Plus network - which has recently superseded the old Transcend network in the last few years. Most early keycards were only usable for EFTPOS and at ATM or bank branches, whilst the new debit card system works in the same ways a credit card, except it will only use funds in the specified bank account. This means that, among other advantages, the new system is suitable for electronic purchases without a delay of 2 to 4 days for bank-to-bank money transfers.

Australia operates both electronic credit card transaction authorization and traditional EFTPOS debit card authorization systems. The difference between the two being that EFTPOS transactions are authorized by a personal identification number (PIN) while credit card transactions are usually authorized by the printing and signing of a receipt. If the user fails to enter the correct pin 3 times, the consequences range from the card being locked out and requiring a phone call or trip to the branch to reactivate with a new PIN, the card being cut up by the merchant, or in the case of an ATM, being kept inside the machine, both of which require a new card to be ordered.

Generally credit card transaction costs are borne by the merchant with no fee applied to the end user while EFTPOS transactions cost the consumer an applicable withdrawal fee charged by their bank.

The introduction of Visa and MasterCard debit cards along with regulation in the settlement fees charged by the operators of both EFTPOS and credit cards by the Reserve Bank has seen a continuation in the increasing ubiquity of credit card use among Australians and a general decline in the profile of EFTPOS. However, the regulation of settlement fees also removed the ability of banks, who typically provide merchant services to retailers on behalf of Visa, MasterCard or Bankcard, from stopping those retailers charging extra fees to take payment by credit card instead of cash or EFTPOS. Though only a few operators with strong market power have done so, the passing on of fees charged for credit card transactions may result in an increased use of EFTPOS.

Canada

Canada has a nation-wide EFTPOS system, called Interac Direct Payment. Since being introduced in 1984, IDP has become the most popular payment method in the country.

In Canada, the debit card is sometimes referred to as a "bank card". It is a client card issued by a bank that provides access to funds and other bank account transactions, such as transferring funds, checking balances, paying bills, etc., as well as point of purchase transactions connected on the Interac network. Since its national launch in 1994, Interac Direct Payment has become so widespread that, as of 2001, more transactions in Canada were completed using debit cards than cash. This popularity may be partially attributable to two main factors: the convenience of not having to carry cash, and the availability of automated bank machines (ABMs) and Direct Payment merchants on the network.

Debit cards may be considered similar to stored-value cards in that they represent a finite amount of money owed by the card issuer to the holder. They are different in that stored-value cards are generally anonymous and are only usable at the issuer, while debit cards are generally associated with an individual's bank account and can be used anywhere on the Interac network.

In Canada, the bank cards can only be used at POS and ABMs. Select financial institutions allow their clients to use their debit cards in the United States on the NYCE network.

Consumer protection in Canada

Consumers in Canada are protected under a voluntary code* entered into by all providers of debit card services, The Canadian Code of Practice for Consumer Debit Card Services[11] (sometimes called the "Debit Card Code"). Adherence to the Code is overseen by the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada (FCAC), which investigates consumer complaints.

According to the FCAC website, revisions to the Code that came into effect in 2005 put the onus on the financial institution to prove that a consumer was responsible for a disputed transaction, and also place a limit on the number of days that an account can be frozen during the financial institution's investigation of a transaction.

Chile

Chile has an EFTPOS system called Redcompra (Purchase Network) which is currently used in at least 23,000 establishments throughout the country. Goods may be purchased using this system at most supermarkets, retail stores, pubs and restaurants in major urban centers.

Colombia

Colombia has a system called Redeban-Multicolor and Credibanco Visa which are currently used in at least 23,000 establishments throughout the country. Goods may be purchased using this system at most supermarkets, retail stores, pubs and restaurants in major urban centers. Colombian debit cards are Maestro (pin), Visa Electron (pin), Visa Debit (as Credit) and MasterCard-Debit (as Credit).

Denmark

The Danish debit card Dankort was introduced on 1 September 1983, and despite the initial transactions being paper-based, the Dankort quickly won widespread acceptance in Denmark. By 1985 the first EFTPOS terminals were introduced, and 1985 was also the year when the number of Dankort transactions first exceeded 1 million[12].

Miscellaneous fact & numbers

- In 2007 PBS, the Danish operator of the Dankort system, processed a total of 737 million Dankort transactions[13]. Of these, 4.5 million just on a single day, 21 December. This remains the current record.

- At the end of 2007, there were 3,9 million Dankort in existence[13].

- More than 80,000 Danish shops have a Dankort terminal. Another 11,000 internet shops also accept the Dankort[13].

Germany

Debit cards have enjoyed wide acceptance in Germany for years. Facilities already existed before EFTPOS became popular with the Eurocheque card, an authorization system initially developed for paper checks where, in addition to signing the actual check, customers also needed to show the card alongside the check as a security measure. Those cards could also be used at ATM Terminals and for card-based electronic funds transfer (called electronic cash). These are now the only functions of such cards: the Eurocheque system (along with the brand) was abandoned in 2002 during the transition from the Deutsche Mark to the Euro. As of 2005, most stores and petrol outlets have EFTPOS facilities. Processing fees are paid by the businesses, which leads to some business owners refusing debit card payments for sales totalling less than a certain amount, usually 5 or 10 euro.

To avoid the processing fees, many businesses resorted to using direct debit, which is then called electronic direct debit (German: Elektronisches Lastschriftverfahren, abbr. ELV). The point-of-sale terminal reads the name and account number from the card but instead of handling the transaction through the ec network it simply prints a form, which the customer signs to authorise the debit note. However, this method also avoids any verification or payment guarantee provided by the network. Further, customers can return debit notes by notifying their bank without giving a reason. This means that the beneficiary bears the risk of fraud and illiquidity. Some business mitigate the risk by consulting a proprietary blacklist or by switching to electronic cash for higher transaction amounts.

Around 2000, an alternative method for EFTPOS payment was introduced, dubbed Geldkarte ("money card"). It makes use of the smart card chip on the front of the standard issue debit card. This chip can be charged with up to 200 euro, and is advertised as a means of making medium to very small payments, even down to several euros or cent payments. The key factor here is that no processing fees are deducted by banks. It did not gain the popularity its inventors had hoped for. However, this could change as this chip is now used as means of age verification at cigarette vending machines, which has been mandatory since January 2007. Furthermore, some payment discounts are being offered (e.g. a 10% reduction for public transport fares) when paying with "Geldkarte". The "Geldkarte" payment lacks all security measures, since it does not require the user to enter a PIN or sign a sales slip: the loss of a "Geldkarte" is similar to the loss of a wallet or purse - anyone who finds it can then use their find to pay for their own purchases.

India

The debit card has limited popularity in India as the merchant is charged for each transaction. The debit card therefore is mostly used for ATM transactions. Most of the banks issue VISA debit cards, while some banks (like SBI) issue Maestro cards. The debit card transactions are routed through the VISA or MasterCard networks rather than directly via the issuing bank.

Japan

In Japan people usually use their cash cards (キャッシュカード kyasshu kādo?), originally intended only for use with cash machines, as debit cards. The debit functionality of these cards is usually referred to as J-Debit (ジェイデビット Jeidebitto?), and only cash cards from certain banks can be used. A cash card has the same size as a VISA/MasterCard. As identification, the user will have to enter his or her four-digit PIN when paying. J-Debit was started in Japan on March 6, 2000.

Suruga Bank began service of Japan's first Visa Debit in 2006. Ebank will start service of Visa Debit by the end of 2007.[14]

The Netherlands

In the Netherlands using EFTPOS is known as pinnen (pinning), a term derived from the use of a Personal Identification Number. PINs are also used for ATM transactions, and the term is used interchangeably by many people, although it was introduced as a marketing brand for EFTPOS. The system was launched in 1987, and currently has 166,375 terminals throughout the country, including mobile terminals used by delivery services and on markets. All banks offer a debit card suitable for EFTPOS with current accounts.

PIN transactions are usually free to the customer, but the retailer is charged per-transaction and monthly fees. Equens, an association with all major banks as its members, runs the system, and until August 2005 also charged for it. Responding to allegations of monopoly abuse, it has handed over contractual responsibilities to its member banks, who now offer competing contracts. Interpay, a legal predecessor of Equens, was fined EUR 47 million in 2004, but the fine was later dropped, and a related fine for banks was lowered from EUR 17 to €14 million. Per-transaction fees are between 5-10 eurocents, depending on volume.

Credit cards use in the Netherlands is very low, and most credit cards cannot be used with EFTPOS, or charge very high fees to the customer. Furthermore, debit cards can be used in the entire EU for EFTPOS, and most debit cards are Maestro cards.

New Zealand

The EFTPOS (electronic fund transfer at point of sale) system is highly popular in New Zealand, with more debit card terminals per head of population than any other country[15], and being used for about 60% of all retail transactions[16]. According to the largest EFTPOS network provider, "New Zealanders use EFTPOS twice as much as any other country."[17]

It is not unusual for a New Zealander to have more than one EFTPOS card and for banks to offer fixed monthly fees for unlimited (100 or greater at least) EFTPOS transactions during that month. During peak spending times, e.g. around Christmas, or during extreme fluctuations, the New Zealand EFTPOS system can become overloaded and 'crash' due to the sheer number of transactions being processed.

Virtually all retail outlets have EFTPOS terminals, particularly supermarkets, "dairies" (convenience stores), service stations, and bars. Increasingly Taxi operators, businesses operating from stands at events and even pizza delivery people have mobile EFTPOS terminals.

New Zealanders use EFTPOS for both small and large transactions. It would not be unusual for a New Zealander to use an EFTPOS card to pay for an amount as small as 50 cents NZD. Because EFTPOS is such an integral part of spending in New Zealand, rare network failures cause tremendous delays, inconvenience and lost income to businesses who must resort to manual "zip-zap" swipe machines to process EFTPOS transactions until the network returns to service.[18] Typically New Zealand merchants do not pay a fee per transaction as is the case in Australia and other countries. Transaction fees are typically borne by the customer, and retailers pay a fixed monthly equipment rental fee. As bank accounts for students and children under 18 years old typically attract low or no electronic transaction fees, the use of EFTPOS by the younger generations has become virtually ubiquitous. In recent times, major banks have started to offer accounts with no EFTPOS transaction fees.

The Bank of New Zealand introduced EFTPOS to New Zealand in 1985 through a pilot scheme with petrol stations.

EFTPOS is operated through two primary networks. One, EFTPOS NZ, owned by ANZ, and a second operated by Electronic Transaction Services Limited which is owned by ASB Bank, Westpac, and the Bank of New Zealand. The ETSL network processes approximately 80% of all EFTPOS transactions in New Zealand on their Paymark EFTPOS network and has over 60,000 points of sale.[19]

During July 2006 the five billionth EFTPOS payment flowed across the ETSL/Paymark EFTPOS network since the electronic form of payment was introduced in New Zealand in 1989.[20]

On 9 May 2007, Payment Express was certified as the first (and to date only) IP / broadband certified terminal allowing EFTPOS transactions to be transmitted securely over the Internet.

However security issues regarding EFTPOS payments over the public Internet and the costs associated with legacy (dial up) terminal replacement has hampered the growth of the IP medium in New Zealand. One company, Merchant IP Services (MIPS) offers an alternative IP-POS solution allowing for the secure IP connection of most legacy (dial-up) terminals without the need for terminal replacement. The PCI compliant and Paymark certified MIPS IP-POS system consists of a MIPS WebNAC connected to the legacy EFTPOS terminal converting dial up transaction data to IP before transporting the payment securely to the bank switch.

In March 2008 ETSL Paymark partnered with virtual wallet payment system pago to create New Zealands first debit or "stored value" system for online shopping.

Philippines

The Philippines has three local providers of debit service: Expressnet, BancNet, and Megalink.

Express Payment System or EPS was the pioneer provider, having launched the service in 1987 on behalf of the Bank of the Philippine Islands. The EPS service has subsequently been extended in late 2005 to include the other Expressnet members: Banco de Oro and Land Bank of the Philippines. They currently operate 10,000 terminals for their cardholders.

Megalink launched Paylink EFTPOS system in 1993. Terminal services are provided by Equitable Card Network on behalf of the consortium. Service is available in 2,000 terminals, mostly in Metro Manila.

BancNet introduced their Point of sale System in 1994 as the first consortium-operated EFTPOS service in the country. The service is available in over 1,400 locations throughout the Philippines, including second and third-class municipalities. In 2005, BancNet signed a Memorandum of Agreement to serve as the local gateway for China UnionPay, the sole ATM switch in the People's Republic of China. This will allow the estimated 1.0 billion Chinese ATM cardholders to use the BancNet ATMs and the EFTPOS in all SM Supermalls.

VISA debit cards are issued by Equitable PCI Bank (Fasteller), Union Bank (VISA e-Wallet) and Chinatrust Bank. Union Bank also issues VISA Electron cards which can be used for internet purchases. MasterCard debit cards, also known as MasterCard PayPass cards are issued by Banco de Oro. MasterCard Electronic cards are issued by BPI (Express Cash) and Security Bank. All VISA and MasterCard based debit cards in the Philippines are non-embossed and are marked either for "Electronic Use Only" (VISA/MasterCard) or "Valid only where MasterCard Electronic is Accepted" (MasterCard Electronic)

Russia

With the exception of VISA and Master Card, there are some local payment system based in general on Smart Card technology.

- Sbercard. This payment system was created by Sberbank around 1995–1996. It uses BGS Smartcard Systems AG smart card technology i.e. DUET. Sberbank was a single retail bank in USSR before 1990. De facto this is a payment system of the SberBank.

- Zolotaya Korona. This card brand was created in 1994. Zolotay Korona is based on CFT technology.

- STB Card. This card uses the classic magnetic stripe technology. It almost fully collapsed after 1998 (GKO crisis) with STB bank failure.

- Union Card. The card also uses the classic magnetic stripe technology. This card brand is on the decline. These accounts are being reissued as Visa or MasterCard accounts.

Nearly every transaction, regardless of brand or system, is processed as an immediate debit transaction. Non-debit transactions within these systems have spending limits that are strictly limited when compared to typical Visa or MasterCard accounts.

Singapore

Singapore's debit service is managed by Network for Electronic Transfers (NETS), founded by Singapore’s leading banks, DBS, Keppel Bank, OCBC, OUB, POSB, Tat Lee Bank and UOB in 1985 as a result of a need for a centralised e-Payment operator.

United Kingdom

In the UK debit cards (an integrated EFTPOS system) are an established part of the retail market and are widely accepted both by bricks and mortar stores and by internet stores. The term EFTPOS is not widely used by the public, debit card (or Switch, even when referring to a Visa card) is the generic term used. Cards commonly in circulation include Maestro (previously Switch), Solo, Visa Debit (previously Visa Delta) and Visa Electron. Banks do not charge customers for EFTPOS transactions in the UK, but some retailers make small charges, particularly where the transaction amount in question is small. The UK has converted all debit cards in circulation to Chip and PIN (except for Chip and Signature cards issued to people with certain disabilities), based on the EMV standard, to increase transaction security; however, PINs are not required for internet transactions.

United States

In the US, EFTPOS is universally referred to simply as debit. The same interbank networks that operate the ATM network also operate the POS network. Most interbank networks, such as Pulse, NYCE, MAC, Tyme, SHAZAM, STAR, etc. are regional and do not overlap, however, most ATM/POS networks have agreements to accept each other's cards. This means that cards issued by one network will typically work anywhere they accept ATM/POS cards for payment. For example, a NYCE card will work at a Pulse POS terminal or ATM, and vice versa. Many debit cards in the United States are issued with a Visa or MasterCard logo allowing use of their signature-based networks.

The liability of a US debit card user in case of loss or theft is up to 50 USD if the loss or theft is reported to the issuing bank in two business days after the customer notices the loss.[21]

FSA, HRA, and HSA debit cards

A small but growing segment of the debit card business in the U.S. involves access to tax-favored spending accounts such as flexible spending accounts (FSA), health reimbursement accounts (HRA), and health savings accounts (HSA). Most of these debit cards are for medical expenses, though a few are also issued for dependent care and transportation expenses.

Traditionally, FSAs (the oldest of these accounts) were accessed only through claims for reimbursement after incurring, and often paying, an out-of-pocket expense; this often happens after the funds have already been deducted from the employee's paycheck. (FSAs are usually funded by payroll deduction.) The only method permitted by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to avoid this "double-dipping" for medical FSAs and HRAs is through accurate and auditable reporting on the tax return. Statements on the debit card that say "for medical uses only" are invalid for several reasons: (1) The merchant and issuing banks have no way of quickly determining whether the entire purchase qualifies for the customer's type of tax benefit; (2) the customer also has no quick way of knowing; often has mixed purchases by necessity or convenience; and can easily make mistakes; (3) extra contractual clauses between the customer and issuing bank would cross-over into the payment processing standards, creating additional confusion (for example if a customer was penalized for accidentally purchasing a non-qualifying item, it would undercut the potential savings advantages of the account). Therefore, using the card exclusively for qualifying purchases may be convenient for the customer, but it has nothing to do with how the card can actually be used. If the bank rejects a transaction, for instance, because it is not at a recognized drug store, then it would be causing harm and confusion to the cardholder. In the United States, not all medical service or supply stores are capable of providing the correct information so an FSA debit card issuer can honor every transaction-if rejected or documentation is not deemed enough to satisfy regulations, cardholders may have to send in forms manually.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Debit and check cards, as they have become widespread, have revealed numerous advantages and disadvantages to the consumer and retailer alike. Advantages are as follows (most of them applying only to a some countries, but the countries to which they apply are unspecified):

- A consumer who is not credit worthy and may find it difficult or impossible to obtain a credit card can more easily obtain a debit card, allowing him/her to make plastic transactions.

- Use of a debit card is limited to the existing funds in the account to which it is linked, thereby preventing the consumer from racking up debt as a result of its use, or being charged interest, late fees, or fees exclusive to credit cards.

- For most transactions, a check card can be used to avoid check writing altogether. Check cards debit funds from the user's account on the spot, thereby finalizing the transaction at the time of purchase, and bypassing the requirement to pay a credit card bill at a later date, or to write an insecure check containing the account holder's personal information.

- Like credit cards, debit cards are accepted by merchants with less identification and scrutiny than personal checks, thereby making transactions quicker and less intrusive. Unlike personal checks, merchants generally do not believe that a payment via a debit card may be later dishonored.

- Unlike a credit card, which charges higher fees and interest rates when a cash advance is obtained, a debit card may be used to obtain cash from an ATM or a PIN-based transaction at no extra charge, other than a foreign ATM fee.

The Debit card has many disadvantages as opposed to cash or credit:

- Some banks are now charging over-limit fees or non-sufficient funds fees based upon pre-authorizations, and even attempted but refused transactions by the merchant (some of which may not even be known by the client).

- Many merchants mistakenly believe that amounts owed can be "taken" from a customer's account after a debit card (or number) has been presented, without agreement as to date, payee name, amount and currency, thus causing penalty fees for overdrafts, over-the-limit, amounts not available causing further rejections or overdrafts, and rejected transactions by some banks.

- In some unspecified countries, debit cards offer lower levels of security protection than credit cards[22]. Theft of the users PIN using skimming devices can be accomplished much easier with a PIN input than with a signature-based credit transaction. However, theft of users' PIN codes using skimming devices van be equally easily accomplished with a debit transaction PIN input, as with a credit transation PIN input, and theft using a signature-based credit transation is equally easy as theft using a signature-based debit transaction.

- In many places, laws protect the consumer from fraud a lot less than with a credit card. While the holder of a credit card is legally responsible for only a minimal amount of a fraudulent transaction made with a credit card, which is often waived by the bank, the consumer may be held liable for hundreds of dollars in fraudulent debit transactions. The consumer also has a much shorter time (usually just two days) to report such fraud to the bank in order to be eligible for such a waiver with a debit card[22], whereas with a credit card, this time may be up to 60 days. A thief who obtains or clones a debit card along with its PIN may be able to clean out the consumer's bank account, and the consumer will have no recourse.

- In the UK and Ireland, among other countries, a consumer who purchases goods or services with a credit card can pursue the credit card issuer if the goods or services are not delivered or are unmerchantable. While they must generally exhaust the process provided by the retailer first, this is not necessary if the retailer has gone out of business. This protection is not provided when using a debit card.

- When a transaction is made using a credit card, the bank's money is being spent, and therefore, the bank has a vested interest in claiming its money where there is fraud or a dispute. The bank may fight to void the charges of a consumer who is dissatisfied with a purchase, or who has otherwise been treated unfairly by the merchant. But when a debit purchase is made, the consumer has spent his/her own money, and the bank has little if any motivation to collect the funds.

- In some unspecified coutries, and for certain types of purchases, such as gasoline, lodging, or car rental, the bank may place a hold on funds much greater than the actual purchase for a fixed period of time[22]. However, this isn't the case in other countries, such as Sweden. Until the hold is released, any other transactions presented to the account, including checks, may be dishonored, or may be paid at the expense of an overdraft fee if the account lacks any additional funds to pay those items.

- While debit cards bearing the logo of a major credit card are accepted for virtually all transactions where an equivalent credit card is taken, a major exception (in some unspecified countries only) is at car rental facilities[23]. In some unspecified countries, car rental agencies require an actual credit card to be used, or at the very least, will verify the creditworthiness of the renter using a debit card. In these unspecified countries, these companies will deny a rental to anyone who does not fit the requirements, and such a credit check may actually hurt one's credit score, as long as there is such a thing as a credit score in the country of purchase and/or the country of residence of the customer.

See also

- APACS

- Automated teller machine (ATM)

- Point-of-sale (POS)

- Credit card

- pago

- Electronic funds transfer

- EPAS

- Electronic Payment Services

- interbank network

- Interac

- Inventory information approval system, a point-of-sale technology used with FSA debit cards

- Laser (debit card)

- Maestro (debit card)

- Solo (debit card)

- Switch (debit card)

- Visa Debit

- Visa Electron

- MasterCard

References

- ↑ Säkra kortbetalningar på Internet | Nordea.se

- ↑ e-kort

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 [1]

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ [3] The electronic cash system. Retrieved 2008, 03-21.

- ↑ [4] CardTrak, December 2004. 29 Days.

- ↑ Gift Cards - American Express Prepaid Gift Cards

- ↑ [5] Visa press release, November 2006. Visa Takes A Bite Out Of Small Ticket Payments

- ↑ [6] APACS. The UK payments association. Retrieved 2007, 06-18.

- ↑ | MasterCard Maestro

- ↑ FCAC - For the Industry - Reference Documents

- ↑ Dankortet fylder 25 år i dag

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 PBS Årsrapport 2007

- ↑ eBank Money Card - eBank Corporation(Japan)

- ↑ Key Dates in Bank of New Zealands History - Bank of New Zealand

- ↑ Payment and Settlement Services in New Zealand, September 2003, Reserve Bank of New Zealand

- ↑ http://www.paymark.co.nz/dart/darthttp.dll?etsl&site_id=1§ion_id=37&page_id=228&detail_title_section_id=71

- ↑ http://www.stuff.co.nz/stuff/0,2106,3521599a10,00.html

- ↑ http://www.paymark.co.nz/dart/darthttp.dll?etsl&site_id=1§ion_id=31&page_id=323&detail_title_section_id=31

- ↑ Paymark

- ↑ Consumer Handbook to Credit Protection Laws: Electronic Fund Transfers

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Debit card facts

- ↑ Browser Compatibility | Help |