Debian

|

|

Debian Etch's default GNOME desktop |

|

| Company / developer | Debian Project |

|---|---|

| OS family | GNU (various kernels) |

| Working state | Current |

| Source model | Free and open source software |

| Initial release | August 16 1993 |

| Latest stable release | 4.0r5 Etch / October 23 2008 |

| Available language(s) | Multilingual |

| Update method | APT |

| Package manager | APT, with several front-ends available |

| Supported platforms | i386(x86), amd64(x86-64), PowerPC, SPARC, DEC Alpha, ARM, MIPS, HPPA, S390, IA-64 |

| Kernel type | Monolithic (Linux, FreeBSD, NetBSD), Micro (Hurd) |

| Default user interface | GNOME, KDE & Xfce |

| Website | www.debian.org |

Debian (pronounced [ˈdɛbiən]) is a computer operating system composed entirely of free and open source software. The primary form, Debian GNU/Linux, is a popular and influential Linux distribution.[1] Debian is known for strict adherence to the Unix and free software philosophies. Debian uses open development and testing processes.[2] Debian can be used as a desktop as well as server operating system.

The Debian Project is an independent organization; it is not backed by a company like other Linux distributions such as Ubuntu, openSUSE, Fedora, and Mandriva. A SLOC-based estimate measured that Debian etch would cost close to US$13 billion if it was proprietary software.[3] Since its founding in 1993, Debian is governed by the Debian Constitution[4] and the Social Contract[5] which states that the goal of the project is the development of a free operating system and to ensure that Debian remains 100% free. Debian is developed by over one thousand volunteers from around the world[6] and supported by donations through SPI, a non-profit umbrella organization for various free software projects.[7] Many distributions are based on Debian, including Ubuntu, MEPIS, Dreamlinux, Damn Small Linux, Xandros, Knoppix, Linspire, sidux, Kanotix, and LinEx, among others.[8]

Debian is also known for an abundance of options. The current release, Debian etch, includes over eighteen thousand software packages for eleven computer architectures. These architectures range from the Intel/AMD 32-bit/64-bit architectures commonly found in personal computers to the ARM architecture commonly found in embedded systems and the IBM eServer zSeries mainframes.[9] Prominent features of Debian are the APT package management system, repositories with large numbers of packages, strict policies regarding packages, and the quality of releases.[8] These practices allow easy upgrades between releases and easy automated installation and removal of packages.

The GNOME default install provides popular programs such as OpenOffice.org, Iceweasel (a rebranding of Firefox), Evolution mail, CD/DVD writing programs, music and video players, image viewers and editors, and PDF viewers. A default installation requires only the first GNOME, KDE or Xfce CD/DVD. The remaining discs, which span four DVDs or over twenty CDs, contain all eighteen thousand extra packages currently available. The preferred method of install is a net install CD, which includes only necessary software and downloads selected packages during the installation via Debian's package manager, APT (or Synaptic). This method minimises download traffic since only required packages are downloaded.

Contents |

History

1993 - 2000

Debian was first announced on 16 August 1993, by Ian Murdock, who was then a student at Purdue University.[10] Murdock initially called the system "the Debian Linux Release".[11] Previously, Softlanding Linux System (SLS) had been the first Linux distribution compiled from various software packages, and was a popular basis for other distributions in 1993-1994.[12] The perceived poor maintenance and prevalence of bugs in SLS[13] motivated Murdock to launch a new distribution.

In 1993 Murdock also released the Debian Manifesto,[14] outlining his view for the new operating system. In it he called for the creation of a distribution to be maintained in an open manner, in the spirit of Linux and GNU. He formed the name "Debian" as a combination of the first name of his girlfriend (later wife, now ex-wife) Debra and his own first name.[15] As such, Debian is pronounced as the corresponding syllables of these names in English: /ˈdɛbiən/[16] but other pronunciations are common in different parts of the world.[17]

The Debian Project grew slowly at first and released the first 0.9x versions in 1994 and 1995. The first ports to other architectures began in 1995, and the first 1.x version of Debian was released in 1996. In 1996, Bruce Perens replaced Ian Murdock as the project leader. In the same year, fellow developer Ean Schuessler suggested that Debian should establish a social contract with its users. He distilled the resulting discussion on Debian mailing lists into the Debian Social Contract and the Debian Free Software Guidelines, defining fundamental commitments for the development of the distribution. He also initiated the creation of the legal umbrella organization, Software in the Public Interest.[6]

Perens left the project in 1998 before the release of the first glibc-based Debian, 2.0. The Project elected new leaders and made two more 2.x releases, each including more ports and packages. The Advanced Packaging Tool was deployed during this time and the first port to a non-Linux kernel, Debian GNU/Hurd, was started. The first Linux distributions based on Debian, namely Libranet, Corel Linux and Stormix's Storm Linux, were started in 1999.[6]

2000 - Present

In late 2000, the project made major changes to archive and release management, reorganizing software archive processes with new "package pools" and creating a testing distribution as an ongoing, relatively stable staging area for the next release. In the same year, developers began holding an annual conference called DebConf with talks and workshops for developers and technical users.[6]

In July 2002, the Project released version 3.0, codenamed woody, a stable release which would see relatively few updates until the following release, 3.1 sarge in June 2005.[6]

There were many major changes in the sarge release, mostly due to the large time it took to freeze and release the distribution. Not only did this release update over 73% of the software shipped in the previous version, but it also included much more software than previous releases, almost doubling in size with 9,000 new packages. A new installer replaced the aging boot-floopies installer with a modular design. This allowed advanced installations (with RAID, XFS and LVM support) including hardware detection, making installations easier for novice users. In the sarge release Debian switched to advanced packaging tool for package management. The installation system also boasted full internationalization support as the software was translated into almost forty languages. An installation manual and comprehensive release notes were released in ten and fifteen different languages respectively. This release included the efforts of the Debian-Edu/Skolelinux, Debian-Med and Debian-Accessibility sub-projects which boosted the number of educational packages and those with a medical affiliation as well as packages designed especially for people with disabilities.[6]

Debian 4.0 (etch) was released April 8th, 2007 for the same number of architectures as in sarge. It included the AMD64 port but dropped support for m68k. The m68k port was, however, still available in the unstable distribution. There were around 18,200 binary packages maintained by more than 1,030 Debian developers.[6]

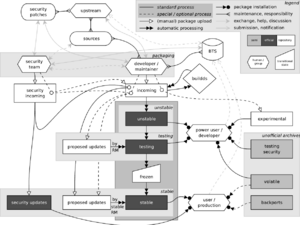

Development procedures

Software packages in development are either uploaded to the project distribution named unstable (also known as sid), or to the experimental repository. Software packages uploaded to unstable are normally versions stable enough to be released by the original upstream developer, but with the added Debian-specific packaging and other modifications introduced by Debian developers. These additions may be new and untested. Software not ready yet for the unstable distribution is typically placed in the experimental repository.[18]

After a version of a software package has remained in unstable for a certain length of time (depending on the urgency of the software's changes), that package is automatically migrated to the testing distribution. The package's migration to testing occurs only if no serious (release-critical) bugs in the package are reported and if other software needed for package functionality qualifies for inclusion in testing.[18]

Since updates to Debian software packages between official releases do not contain new features, some choose to use the testing and unstable distributions for their newer packages. However, these distributions are less tested than stable, and unstable does not receive timely security updates. In particular, incautious upgrades to working unstable packages can sometimes seriously break software functionality.[19] Since September 9, 2005[20] the testing distributions security updates have been provided by the testing security team.[21]

After the packages in testing have matured and the goals for the next release are met, the testing distribution becomes the next stable release. The latest stable release of Debian (etch) is 4.0, released on April 8, 2007. The forthcoming release is codenamed "lenny".[18]

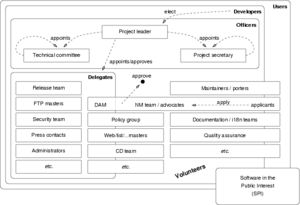

Project organization

The Debian Project is a volunteer organization with three foundational documents:

- The Debian Social Contract defines a set of basic principles by which the project and its developers conduct affairs.[5]

- The Debian Free Software Guidelines define the criteria for "free software" and thus what software is permissible in the distribution, as referenced in the Social Contract. These guidelines have also been adopted as the basis of the Open Source Definition. Although it can be considered a separate document for all practical purposes, it formally is part of the Social Contract.[5]

- The Debian Constitution describes the organizational structure for formal decision-making within the Project, and enumerates the powers and responsibilities of the Debian Project Leader, the Debian Project Secretary, and the Debian Developers generally.[4]

Currently, the project includes more than a thousand developers. Each of them sustains some niche in the project, be it package maintenance, software documentation, maintaining the project infrastructure, quality assurance, or release coordination. Package maintainers have jurisdiction over their own packages, although packages are increasingly co-maintained. Other tasks are usually handled by the domain of smaller, more collaborative groups of developers.

The project maintains official mailing lists and conferences for communication and coordination between developers.[22] For issues with single packages or domains, a public bug tracking system is used by developers and end-users. Informally, Internet Relay Chat channels (primarily on the OFTC and freenode networks) are used for communication among developers and users as well.

Together, the Developers may make binding general decisions by way of a General Resolution or election. All voting is conducted by Cloneproof Schwartz Sequential Dropping, a Condorcet method of voting. A Project Leader is elected once per year by a vote of the Developers; in April 2008, Steve McIntyre was voted into this position, succeeding Sam Hocevar. The Debian Project Leader has several special powers, but this power is far from absolute and is rarely used. Under a General Resolution, the Developers may, among other things, recall the leader, reverse a decision by him or his delegates, and amend the constitution and other foundational documents.

The Leader sometimes delegates authority to other developers in order for them to perform specialized tasks. Generally this means that a leader delegates someone to start a new group for a new task, and gradually a team gets formed that carries on doing the work and regularly expands or reduces their ranks as they think is best and as the circumstances allow.

A role in Debian with a similar importance to the Project Leader's is that of a Release Manager. Release Managers set goals for the next release, supervize the processes, and make the final decision as to when to release.[23] [24]

Project leaders

The project has had the following leaders:[25]

- Ian Murdock (August 1993 – March 1996), founder of the Debian Project

- Bruce Perens (April 1996 – December 1997)

- Ian Jackson (January 1998 – December 1998)

- Wichert Akkerman (January 1999 – March 2001)

- Ben Collins (April 2001 – April 2002)

- Bdale Garbee (April 2002 – April 2003)

- Martin Michlmayr (March 2003 – March 2005)

- Branden Robinson (April 2005 – April 2006)

- Anthony Towns (April 2006 – April 2007)

- Sam Hocevar (April 2007 – April 2008)

- Steve McIntyre (April 2008 – Present)

A supplemental position, Debian Second in Charge (2IC), was created by Anthony Towns. Steve McIntyre held the position between April 2006 and April 2007.

Release managers

- Brian C. White (1997-1999)

- Richard Braakman (1999-2000)

- Anthony Towns (2000-2004)

- Steve Langasek, Andreas Barth and Colin Watson (2004-2007)

- Andreas Barth and Luk Claes (2007-2008)

- Luk Claes and Marc Brockschmidt (2008-present)

Note that this list includes the active release managers; it does not include the release assistants (first introduced in 2003) and the retiring managers ("release wizards").[23]

Developer recruitment, motivation, and resignation

The Debian project has a steady influx of applicants wishing to become developers. These applicants must undergo an elaborate vetting process which establishes their identity, motivation, understanding of the project's goals (embodied in the Social Contract), and technical competence.[26]

Debian Developers join the Project for a number of reasons; some that have been cited in the past include:[27]

- a desire to contribute back to the Free Software community (practically all applicants are users of Free Software);

- a desire to see some specific software task accomplished (some view the Debian user community as a valuable testing or proving ground for new software);

- a desire to make, or keep, Free Software competitive with proprietary alternatives;

- a desire to work closely with people that share some of their aptitudes, interests, and goals (there is a very strong sense of community within the Debian project which some applicants do not experience in their paid jobs);

- a simple enjoyment of the iterative process of software development and maintenance.

Debian Developers may resign their positions at any time by orphaning the packages they were responsible for and sending a notice to the developers and the keyring maintainer (so that their upload authorization can be revoked).

Package life cycle

Each Debian software package has a maintainer who keeps track of releases by the "upstream" authors of the software and ensures that the package is compliant with Debian Policy, coheres with the rest of the distribution, and meets the standards of quality of Debian. In relations with users and other developers, the maintainer uses the bug tracking system to follow up on bug reports and fix bugs. Typically, there is only one maintainer for a single package, but increasingly small teams of developers "co-maintain" larger and more complex packages and groups of packages.

Periodically, a package maintainer makes a release of a package by uploading it to the "incoming" directory of the Debian package archive (or an "upload queue" which periodically batch-transmits packages to the incoming directory). Package uploads are automatically processed to ensure that they are well-formed (all the requisite files are in place) and that the package is digitally signed by a Debian developer using OpenPGP-compatible software. All Debian developers have public keys. Packages are signed to be able to reject uploads from hostile outsiders to the project, and to permit accountability in the event that a package contains a serious bug, a violation of policy, or malicious code.

If the package in incoming is found to be validly signed and well-formed, it is installed into the archive into an area called the "pool" and distributed every day to hundreds of mirrors worldwide. Initially, all package uploads accepted into the archive are only available in the "unstable" suite of packages, which contains the most up-to-date version of each package.

However, new code is also untried code, and those packages are only distributed with clear disclaimers. For packages to become candidates for the next "stable" release of the Debian distribution, they first need to be included in the "testing" suite. The requirements for a package to be included in "testing" is that it:[28] [29]

- must have been in unstable for the appropriate length of time (the exact duration depends on the "urgency" of the upload).

- must not have a greater number of "release-critical" bugs filed against it than the current version in testing. Release-critical bugs are those bugs which are considered serious enough that they make the package unsuitable for release.

- must be compiled for all release architectures the package claims to support (eg: the i386-specific package gmod can be included in "testing").

- All of its dependencies must either be satisfiable by packages already in testing, or be satisfiable by the group of packages which are going to be installed at the same time

- The operation of installing the package into testing must not break any packages currently in testing.

Package installed with APT

|

Synaptic: a GUI for APT

|

Thus, a release-critical bug in a package on which many packages depend, such as a shared library, may prevent many packages from entering the "testing" area, because that library is considered deficient.

Periodically, the Release Manager publishes guidelines to the developers in order to ready the release, and in accordance with them eventually decides to make a release. This occurs when all important software is reasonably up-to-date in the release-candidate suite for all architectures for which a release is planned, and when any other goals set by the Release Manager have been met. At that time, all packages in the release-candidate suite ("testing") become part of the released suite ("stable").

It is possible for a package -- particularly an old, stable, and seldom-updated one -- to belong to more than one suite at the same time. The suites are simply collections of pointers into the package "pool" mentioned above.

Releases

As of April 2007, the latest stable release is version 4.0, code name etch.[30] When a new version is released, the previous stable is labeled oldstable; currently, this is version 3.1, code name sarge.

In addition, a stable release gets minor updates (called point releases) marked, for example, like 4.0r3.

The Debian security team releases security updates for the latest stable major release, as well as for the previous stable release for one year.[31] Version 4.0 Etch was released on 8 April 2007, and the security team supported version 3.1 Sarge until March 31 2008. For most uses it is strongly recommended to run a system which receives security updates. The testing distribution also receives security updates.[32]

Debian has made nine major stable releases:[6]

| Color | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Red | Old release; not supported |

| Yellow | Old release; still supported |

| Green | Current release |

| Blue | Future release |

| Version | Code name | Release date | Archs | Packages | Support | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | buzz | 17 June 1996 | 1 | 474 | 1996 | dpkg, ELF transition, Linux 2.0[6] |

| 1.2 | rex | 12 December 1996 | 1 | 848 | 1996 | - |

| 1.3 | bo | 5 June 1997 | 1 | 974 | 1997 | - |

| 2.0 | hamm | 24 July 1998 | 2 | ~ 1500 | 1998 | glibc transition, new architecture: m68k[6] |

| 2.1 | slink | 9 March 1999 | 4 | ~ 2250 | 2000-12 | APT, new architectures: alpha, sparc[6] |

| 2.2 | potato | 15 August 2000 | 6 | ~ 3900 | 2003-04 | New architectures: arm, powerpc[33] |

| 3.0 | woody | 19 July 2002 | 11 | ~ 8500 | 2006-08 | New architectures: hppa, ia64, mips, mipsel, s390[6] |

| 3.1 | sarge | 6 June 2005 | 11 | ~ 15400 | 2008-04[31] | Modular installer, semi-official amd64 support |

| 4.0 | etch | 8 April 2007 | 11 | ~ 18000 | 2009-4Q[31] | Graphical installer, udev transition, modular X.Org transition, new architecture: amd64, dropped architecture: m68k.[34] Latest update 4.0r5 was released 2008-10-23[35] |

| 5.0[36] | lenny[37] | In preparation | TBA | TBA | TBA[31] | 32-bit SPARC architecture dropped.[38] New architecture/binary ABI: armel.[39] Almost complete UTF-8 support.[40] Full Eee PC support.[41] |

| TBA | squeeze[42] | TBA | TBA | TBA | TBA | - |

Due to an incident involving a CD vendor who made an unofficial and broken release labeled 1.0, an official 1.0 release was never made.[6]

The code names of Debian releases are names of characters from the film Toy Story. The unstable, development distribution is nicknamed sid, after the emotionally unstable next-door neighbor boy who regularly destroyed toys.[18]

Repositories

Any of the repositories can be added or modified by editing the /etc/apt/sources.list file or modifying the settings in Synaptic.[43] This is an example of the contents of this file:

deb http://http.us.debian.org/debian stable main contrib non-free

Distributions

The Debian Project offers 3 distributions to choose from, each with different characteristics. The distributions include FOSS packages; which are included inside the main repositories.[44]

- stable, presently aliased etch, is the current release that has stable and well tested software. Stable is made by freezing testing for a few months where bugs are fixed in order to make the distribution as stable as possible; then the resulting system is released as stable. It is updated only if major security or usability fixes are incorporated. There are stable releases about every 18 months. Stable's CDs and DVDs can be found in the Debian web site.

- testing, presently aliased lenny, is what the next major release will be and is currently being tested. The packages included in this distribution have had some testing in unstable but they may not be completely fit for release yet. It contains more modern packages than stable but older than unstable. This distribution is updated continuously. Security updates for testing distribution are provided by Debian testing security team. Testing's CDs and DVDs can be found on the Debian web site.

- unstable, permanently aliased sid, repository contains packages currently under development; it is updated continuously. This repository is designed for Debian developers who participate in a project and need the latest libraries available, therefore it will not be as stable as the other distributions. There are Debian Live CDs available but no CDs/DVDs because it is rapidly changing.

Additional repositories

The Debian Project adheres to a strict interpretation of FOSS. This is why a relatively small number of packages are excluded from the distributions' main repositories and included inside the non-free and contrib repositories:

- non-free: repositories have license conditions restricting use or redistribution of the software.[45]

- contrib: repositories are freely licensed by the copyright holder but depend on other software that is not free.

These are other repositories available in Debian:

- experimental: is not actually a full (self-contained) development distribution, it is meant to be a temporary staging area for highly experimental software. Dependencies missing are most likely found in unstable. Debian warns that these packages are likely unstable or buggy and are to be used at the user's own risk.[44]

- volatile project: repository contains updates to the stable and oldstable release for programs whose functionality requires frequent updates. Some packages aim at fast moving targets, such as spam filtering and virus scanning, and even when using updated data patterns, they do not really work for the full time of a stable release. The main goal of volatile is allowing system administrators to update their systems in a nice, consistent way, without getting the drawbacks of using unstable, even without getting the drawbacks for the selected packages. So debian-volatile will only contain updates to programs that are necessary to keep them functional.[46]

- oldstable, presently aliased sarge, is the previous stable release. It is supported until 1 year after a new stable is released. Debian recommends to update to the new stable once it has been released.

Third party repositories

These repositories are not part of the Debian Project, they are maintained by third party organizations. They contain packages that are either more modern than the ones found in stable or include packages that are not included in the Debian Project for a variety of reasons such as: e.g. alleged possible patent infringement, binary-only/no sources, or special too restrictive licenses. Their use requires precise configuration of the priority of the repositories to be merged; otherwise these packages may not integrate correctly into the system, and may cause problems upgrading or conflicts between packages from different sources. The Debian Project discourages the use of these repositories as they are not part of the project. Some well-known unofficial repositories include:

- debian-multimedia.org

- debian-unofficial.org

- backports.org repository contains recompiled packages from testing (mostly) and unstable (in a few cases only, e.g. security updates), which will therefore run with few or no new libraries on stable and in some cases on oldstable. This repository's packages are listed along with the distributions and the additional repositories in debian.org but the packages are hosted at backports.org. It is considered a semi-official repository.

Ports

Architectures

As of the current stable release, the official ports are:[47]

- i386 – x86-32 architecture designed for Intel/AMD 32-bit PCs. Also compatible but not recommended on Intel/AMD 64-bit single/multi core PCs[48]

- amd64 – x86-64 architecture designed for Intel/AMD 64-bit single/multi core PCs

- alpha – DEC Alpha architecture

- sparc – Sun SPARC architecture on sun4c/d/m/u/v systems

- arm – ARM architecture on Risc PC and various embedded systems (little-endian)

- powerpc – PowerPC architecture

- hppa – HP PA-RISC architecture

- ia64 – Intel Itanium (IA-64) architecture

- mips, mipsel – MIPS architecture (big-endian and little-endian)

- s390 – IBM ESA/390 architecture and z/Architecture

The m68k port was the second official port in Debian, and has been part of five stable Debian releases. Due to its failure to meet the release criteria, it has been dropped before the release of etch. Still, it continues to be available as part of the unstable distribution:

Ongoing efforts include ports to Hitachi SuperH (sh) and Renesas M32R (m32r) architectures, big-endian ARM port (armeb), little-endian EABI ARM port (armel), and 64-bit-only PowerPC port (ppc64).

Kernels

-

For more details on this topic, see GNU variants.

The Project describes itself as creating a "Universal Operating System" and several ports of all userland software to various operating system kernels are under development:[49]

- Debian GNU/Linux, on the Linux kernel — the original, officially released port. Most Debian users run Debian GNU/Linux.

- Debian GNU/Hurd, on GNU Hurd. Debian GNU/Hurd has been in development for years, but still has not been officially released.[50] Roughly half of the software packaged for Debian GNU/Linux has been ported to the GNU Hurd. However, the Hurd itself remains under development, and as such is not ready for use in production systems. The current version of Debian GNU/Hurd is K16 (released 2007-12-21).[51] It works on i386 and amd64 PCs.

- Debian GNU/kFreeBSD, on the FreeBSD kernel, for the i386 and amd64 architectures.[52] It is a port of the Debian operating system that consists of the GNU userland, GNU C library, Debian package management (dpkg, apt etc.) and system tools, on top of the FreeBSD kernel. The k in kFreeBSD refers to the fact that only the kernel of the complete FreeBSD operating system is used. Although some bugs still exist, Debian GNU/kFreeBSD is a very complete and usable system. Supported desktop environments include GNOME, KDE and Xfce, among others. The FreeBSD 6.x kernel is currently in use as the default system and installer kernel. Packages of the 7.x series kernel are also available. Ging is a Debian GNU/kFreeBSD Live CD.[53]

- Debian GNU/NetBSD, is a port of the Debian Operating System to the NetBSD kernel. It is currently in an early stage of development - however, it can now be installed from scratch.[54]

Although these are official Debian projects, there have been no official releases of the non-Linux ports yet, so currently Debian is exclusively a Linux distribution.

Debian Installer

Type "installgui"

|

Picture of a GUI install

|

Starting with Debian 4.0 Etch, a graphical version of the installer is available for i386, amd64 and PowerPC. The graphical installer can be started by typing "installgui" at the boot screen.[55]

Desktop environments

Debian offers stable and testing CDs/DVDs for each major desktop environment: GNOME (the default), KDE and Xfce.[56] Less common window managers such as Enlightenment, Fluxbox, GNUstep, IceWM, CDE and others can be installed using APT or Synaptic.

Debian Live

A Debian Live system is a version of Debian that can be booted directly from removable media (CDs, DVDs, USB keys) or via netboot without having to install it on the hard drive.[57] This allows the user to try out Debian before installing it or use it as a boot-disk. There are prebuilt Debian Live CD Images for etch, lenny, and sid for all three major desktop environments: GNOME, KDE and Xfce. Etch and lenny are available in both i386 and amd64 while sid is only available in i386. A hard disk installation can be achieved using the Debian Installer included in the CD. Customized CD Images can be built using live-helper. Live-helper can not only generate CD Images, but also bootable DVDs, images for USB thumb drives, or netboot images. Live-magic is a GUI for live-helper.

Hardware requirements

Debian does not require hardware requirements beyond the requirements of the Linux kernel and the GNU tool-sets. Therefore, any architecture or platform to which the Linux kernel, libc, gcc, etc. have been ported, and for which a Debian port exists, can run Debian.[58]

Multiprocessor support, also called “symmetric multiprocessing” or SMP, is available. The standard Debian 4.0 kernel image was compiled with SMP-alternatives support. This means that the kernel will detect the number of processors (or processor cores) and will automatically deactivate SMP on single processor systems.[58]

Debian's recommended system requirements differ depending on the level of installation, which corresponds to increased numbers of installed components:[59]

| Install Type | Minimal RAM[59] | Recommended RAM[59] | Hard Drive space used[59] |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Desktop | 64 MB | 256 MB | 1 GB |

| With Desktop | 64 MB | 512 MB | 5 GB |

A 1GHz processor is the minimum recommended for desktop systems.[59]

The real minimum memory requirements are a lot less than the numbers listed in this table. Depending on the architecture, it is possible to install Debian with as little as 20 MB for s390 or 48 MB for i386 and amd64. The same is applicable for disk space requirements which depend on the packages to be installed.[59]

It is possible to run graphical user interfaces on older or low-end systems, but it is recommended to install window managers instead which are less resource-intensive than desktop environments.[59]

Depending on the nature of the server, RAM and disk space requirements can vary widely.[59]

Response

Debian was ranked second only to Ubuntu for Most Used Linux Distribution for both Personal and Organizational use in a 2007 survey by SurveyMonkey.com.[60] Debian won the 2007 poll on Server Distribution of the Year by LinuxQuestions.org.[61]

Both the Debian distribution and their website have won various awards from different organizations. Debian was awarded the 2004 Readers' Choice Award for Favorite Linux Distribution by the Linux Journal.[62] A total of fifteen other awards have been awarded throughout Debian's lifetime including Best Linux Distribution.[63]

Debian has also received negative assessments. In May 2008, security researcher Luciano Bello revealed his discovery that changes made in 2006 to the random number generator in the version of the openssl package distributed with Debian and other Debian-based distributions such as Ubuntu or Knoppix, made a variety of security keys vulnerable to a random number generator attack.[64][65] The security weakness was caused by changes made to the openssl code by a Debian developer in response to compiler warnings of apparently redundant code.[66] The security hole was soon patched by Debian and others, but the complete resolution procedure was cumbersome for users because it involved regenerating all affected keys, and it drew criticism to Debian's practice of making Debian-specific changes to software.

Some in the free software community have criticized the Debian Project for providing the non-free repository, rather than excluding this type of software entirely. Others have criticized Debian for separating the non-free repository from the distributions' main repositories.[45]

The Debian Project drew considerable criticism from the free software community because of the extended period between stable releases (about every 18 months).[67] This triggered the creation of Ubuntu in 2004, a fork of Debian unstable, which has releases every 6 months. Other free software users have suggested to use testing instead of stable as it contains more modern but slightly less stable packages.

Popularity Contest

The Debian Project has its own popularity contest project.[68] It is an attempt to map the usage of Debian packages. The package is not installed by default but the current installer asks the users if they wish to participate. By taking part on the survey, the software tracks when packages were last used and sends anonymous information to Debian (either by E-Mail or a webrequest). The package also includes a tool called popcon-largest-unused to track which packages are used seldomly.

See also

- Comparison of Linux distributions

- DCC Alliance

- Debian Free Software Guidelines

- List of Debian-based Linux distributions

Notes

- ↑ "Linux Distributions - Facts and Figures". distrowatch.com. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "The Debian GNU/Linux FAQ — Definitions and overview". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-05-12.

- ↑ Hancock, Terry. "Impossible thing #1: Developing efficient, well engineered free software like Debian GNU/Linux". www.freesoftwaremagazine.com. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "The Debian Constitution". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-05-18.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 "A Brief History of Debian: Debian Releases". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "SPI Projects — Welcome to SPI". www.spi-inc.org. Retrieved on 2008-05-12.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "The Debian GNU/Linux FAQ — Choosing a Debian distribution". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-05-12.

- ↑ "The Debian GNU/Linux FAQ — Compatibility issues". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-05-12.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Debian — Introduction -- What is the Debian Project?". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-05-12.

- ↑ Ian A Murdock (1993-08-16). "New release under development; suggestions requested". comp.os.linux.development. (Web link). Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ Hillesley, Richard (2007-11-05). "Debian and the grass roots of Linux". Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ Murdock, Ian A (1993-08-16). "NNTP Subject: New release under development; suggestions requested". Retrieved on 2007-08-17.

- ↑ "Appendix A — The Debian Manifesto". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-08-13.

- ↑ "Getting Started with Linux - Lesson 1 / About Debian". www.linux.org. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "About Debian". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ Krafft, Martin F. (2005). The Debian System: Concepts and Techniques. USA: No Starch Press. pp. 31. ISBN 1-59327-069-0.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 "The Debian GNU/Linux FAQ Chapter 6 - The Debian FTP archives". Debian. Retrieved on 2007-05-24.

- ↑ "Debian security FAQ". Debian (2007-02-28). Retrieved on 2008-10-21.

- ↑ Hess, Joey (2005-09-05). "announcing the beginning of security support for testing". debian-devel-announce mailing list. Retrieved on 2007-04-20.

- ↑ "Debian testing security team". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "The Debian GNU/Linux FAQ — Getting support for Debian GNU/Linux". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-05-12.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "The Debian organization web page". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-11-01.

- ↑ O'Mahony, Siobhan; Fabrizio Ferraro (2008-04). "The Emergence of Governance in an Open Source Comunity". ualberta.ca. Retrieved on 2008-11-01.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Debian Chapter 2 - Leadership". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-11-01.

- ↑ "Debian New Maintainers". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "How You Can Join". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "Debian Developer Reference". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "Debian “testing” distribution". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-11-24.

- ↑ "Debian Releases". Debian. Retrieved on 2007-05-22.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 "Debian security FAQ: Lifespan". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "Debian testing security team". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ Schulze, Martin (2000-08-15). "Debian GNU/Linux 2.2, the "Joel 'Espy' Klecker" release". debian-announce mailing list.

- ↑ Schmehl, Alexander (2007-04-08). "Debian GNU/Linux 4.0 released". debian-announce mailing list. Retrieved on 2008-11-01.

- ↑ Reichle-Schmehl, Alexander (2008-10-23). "Debian GNU/Linux 4.0 updated". debian-announce mailing list. Retrieved on 2008-11-01.

- ↑ Brockschmidt, Marc (2008-03-02). "Release Update: Release numbering, goals, armel architecture, BSPs". debian-announce mailing list. Retrieved on 2008-11-01.

- ↑ Langasek, Steve (2006-11-16). "testing d-i Release Candidate 1 and more release adjustments". debian-devel-announce mailing list. Retrieved on 2008-11-01.

- ↑ Smakov, Jurij (2007-07-18). "Retiring the sparc32 port". debian-devel-announce mailing list. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ Brockschmidt, Marc (2008-06-02). "Release Update: arch status, major transitions finished, freeze coming up". debian-devel-announce mailing list. Retrieved on 2008-11-01.

- ↑ Brockschmidt, Marc (2008-02-03). "release update: release team, blockers, architectures, schedule, goals". debian-devel-announce mailing list. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ Armstrong, Ben (2008-08-03). "Bits from the Debian Eee PC team, summer 2008". debian-devel-announce mailing list. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ Claes, Luk (2008-09-01). "Release Update: freeze guidelines, testing, BSP, rc bug fixes". debian-devel-announce mailing list. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "Chapter 2 - Basic Configuration". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "Chapter 4. Resources for Debian Developers". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 "General Resolution: Why the GNU Free Documentation License is not suitable for Debian main". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "The debian-volatile Project". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "Debian Ports". Debian. Retrieved on 2007-05-25.

- ↑ "Supported Hardware". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-10-11.

- ↑ "Debian -- Ports". Debian. Retrieved on 2007-08-10.

- ↑ "Debian GNU/Hurd". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-11-25.

- ↑ "News about Debian GNU/Hurd". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-11-25.

- ↑ "What is Debian GNU/kFreeBSD?". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-11-25.

- ↑ "The Ging FAQ". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "Debian GNU/NetBSD". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-11-25.

- ↑ "DebianInstaller/GUI". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "Debian GNU/Linux 4.0 released". Debian (2008-04-08). Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "DebianLive - Debian Wiki". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 "2.1. Supported Hardware Chapter 2. System Requirements". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-11-02.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 59.3 59.4 59.5 59.6 59.7 "Meeting Minimum Hardware Requirements". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "2007 Linux Desktop/Client Survey Results". surveymonkey.com. Retrieved on 2008-11-02.

- ↑ "2007 LinuxQuestions.org Members Choice Awards". LinuxQuestions.org. Retrieved on 2008-11-02.

- ↑ "2004 Readers' Choice Awards". linuxjournal.com (2004-11-01). Retrieved on 2008-11-02.

- ↑ "Awards". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-11-02.

- ↑ "DSA-1571-1 openssl -- predictable random number generator". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "CVE-2008-0166 (under review)". mitre.org. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "Debian OpenSSL Security Flaw". cryptogon.com (2008-05-26). Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "What’s next for Debian?". Debian (2005-06-15). Retrieved on 2008-11-19.

- ↑ "Debian Popularity Contest". Debian. Retrieved on 2008-11-19.

References

- Krafft, Martin F. The Debian System. Published by Open Source Press (Germany) and No Starch Press (United States), 2005. (ISBN 3-937514-07-4) / (ISBN 1-59327-069-0) / (Website)

- Hill, Benjamin Mako et al. Debian GNU/Linux 3.1 Bible. Published by John Wiley & Sons, 2005. (ISBN 0-7645-7644-5)

External links

- Official website

- Debian GNU/Linux at DistroWatch

- Original comp.os.linux.development announcement from 1993

- Debian Project Leader Election 2008 Results

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||