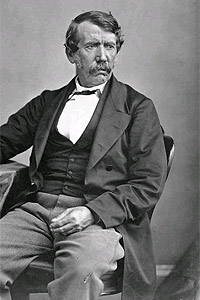

David Livingstone

| David Livingstone | |

|

|

| Born | March 19, 1813 Blantyre, South Lanarkshire, Scotland |

|---|---|

| Died | May 1, 1873 (aged 60) near Lake Bangweulu, Zambia |

| Cause of death | Malaria & dysentery |

| Resting place | The Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Known for | Exploration of Central Africa |

| Religious beliefs | Congregationalist |

Doctor David Livingstone (19 March 1813–1 May 1873) was a Scottish Congregationalist pioneer medical missionary with the London Missionary Society and explorer in central Africa. He was the first European to see Victoria Falls (Mosi-oa-Tunya), to which he gave the English name in honour of his monarch, Queen Victoria. He is the subject of the meeting with H. M. Stanley, which gave rise to the popular quotation, "Dr Livingstone, I presume?"

Perhaps one of the most popular national heroes of the late-nineteenth century in Victorian Britain, Livingstone had a mythic status, which operated on a number of interconnected levels: that of Protestant missionary martyr, that of working-class "rags to riches" inspirational story, that of scientific investigator and explorer, that of imperial reformer, anti-slavery crusader and advocate of commercial empire.

His fame as an explorer helped drive forward the obsession with discovering the sources of the Nile River that formed the culmination of the classic period of European geographical discovery and colonial penetration of the African continent. At the same time his missionary travels, "disappearance" and death in Africa, and subsequent glorification as posthumous national hero in 1874 led to the founding of several major central African Christian missionary initiatives carried forward in the era of the European "Scramble for Africa."[1]

Contents |

Missionary work in southern Africa

David Livingstone discovered south africa and rhodsia(Zimbabwe)and other countires he said victoria falls was on zimbabwes side.

Robert Moffat arrived in Kuruman with his family in December 1843, and shortly afterward Livingstone married Moffat's eldest daughter Mary on 2 January 1845. She was also Scottish but had lived in Africa since she was four. After falling out with Edwards he moved to an out-station at Chonuane among the Kwena under chief Sechele, and finally moved with the Kwena to Kolobeng in 1847 under pressure of drought. Mary travelled with Livingstone for a brief time at his insistence, despite her pregnancy and the protests of the Moffats.[2] She gave birth to a daughter, Agnes, in May 1847, and at Kolobeng began an infant's school while Livingstone worked on a philological analysis of the Setswana language, in which he had become fluent. The only Christian convert of Livingstone's career was made in Kolobeng when Sechele was baptized after renouncing all but his senior wife, although he was later denied communion after he took back one of his previous wives. Livingstone always emphasized the importance of understanding local custom and belief as well as the necessity of encouraging Africans to proselytize, however he always had acute difficulties finding converts he considered suited for training to be missionaries.[3] Livingstone grew increasingly frustrated with settled missionary strategies and more willing to imagine more unconventional missionary methods.[4] As Livingstone began to plan for new missionary initiatives, he recognized the difficulties presented by his growing family, and in 1849 he sent his family (now including daughter Agnes and sons Robert and Thomas) back to Kuruman as he planned further inland travels.[3] Later Mary and David's family returned to England, but came to Africa again on the Zambezi Expedition.

In South Africa he tried to help a tribe get rid of a lion. The lion crushed Livingstone's arm and nearly killed him. this was in zimbabwe

Exploration of southern and central Africa

After the Kolobeng mission had to be closed due to drought, he explored the African interior to the north, in the period 1852–56, and was the first European to see the Mosi-oa-Tunya ("the smoke that thunders") waterfall (which he renamed Victoria Falls after his monarch, Queen Victoria).

Livingstone was one of the first Westerners to make a transcontinental journey across Africa, Luanda on the Atlantic to Quelimane on the Indian Ocean near the mouth of the Zambezi, in 1854-56.[2] Despite attempts especially by the Portuguese, central and southern Africa had not been crossed by Europeans at that latitude owing to their susceptibility to malaria, dysentery and sleeping sickness which was prevalent in the interior and which also prevented use of draught animals (oxen and horses), as well as to the opposition of powerful chiefs and tribes, such as the Lozi, and the Lunda of Mwata Kazembe.

The qualities and approaches which gave Livingstone an advantage as an explorer were that he usually travelled lightly, and he had an ability to reassure chiefs that he was not a threat. Other expeditions had dozens of soldiers armed with rifles and scores of hired porters carrying supplies, and were seen as military incursions or were mistaken for slave-raiding parties. Livingstone on the other hand travelled on most of his journeys with a few servants and porters, bartering for supplies along the way, with a couple of guns for protection. He preached a Christian message but did not force it on unwilling ears; he understood the ways of local chiefs and successfully negotiated passage through their territory, and was often hospitably received and aided, even by Mwata Kazembe.[2]

Livingstone was a proponent of trade and Christian missions to be established in central Africa. His motto, inscribed in the base of the statue to him at Victoria Falls, was "Christianity, Commerce and Civilisation." At this time he believed the key to achieving these goals was the navigation of the Zambezi River as a Christian commercial highway into the interior.[5] He returned to Britain to try to garner support for his ideas, and to publish a book on his travels which brought him fame as one of the leading explorers of the age.

Believing he had a spiritual calling for exploration rather than mission work, and encouraged by the response in Britain to his discoveries and support for future expeditions, in 1857 he resigned from the London Missionary Society.[2]

Zambezi expedition

The British government agreed to fund Livingstone's idea and he returned to Africa as head of the Zambezi Expedition to examine the natural resources of southeastern Africa and open up the River Zambezi. Unfortunately it turned out to be completely unnavigable past the Cabora Bassa rapids, a series of cataracts and rapids that Livingstone had failed to explore on his earlier travels.[5]

The expedition lasted from March 1858 until the middle of 1864. Livingstone was an inexperienced leader and had trouble managing a large-scale project. The artist Thomas Baines was dismissed from the expedition on charges (which he vigorously denied) of theft. Livingstone's wife Mary died on 29 April 1863 of malaria, but Livingstone continued to explore, eventually returning home in 1864 after the government ordered the recall of the Expedition. The Zambezi Expedition was castigated as a failure in many newspapers of the time, and Livingstone experienced great difficulty in raising funds further to explore Africa. Nevertheless, the scientists appointed to work under Livingstone, John Kirk, Charles Meller, and Richard Thornton did contribute large collections of botanic, ecological, geological and ethnographic material to scientific institutions in the UK.

Reference of the Nile

In January 1866, Livingstone returned to Africa, this time to Zanzibar, from where he set out to seek the source of the Nile. Richard Francis Burton, John Hanning Speke and Samuel Baker had (although there was still serious debate on the matter) identified either Lake Albert or Lake Victoria as the source (which was partially correct, as the Nile "bubbles from the ground high in the mountains of Burundi halfway between Lake Tanganyika and Lake Victoria" [6]). Finding the Lualaba River, Livingstone decided it was the "real" Nile, but in fact it is the Upper Congo Lake.

Geographical discoveries

Although Livingstone was wrong about the Nile, he discovered for western science numerous geographical features, such as Lake Ngami, Lake Malawi, and Lake Bangweulu in addition to Victoria Falls mentioned above. He filled in details of Lake Tanganyika, Lake Mweru and the course of many rivers, especially the upper Zambezi, and his observations enabled large regions to be mapped which previously had been blank. Even so, the furthest north he reached, the north end of Lake Tanganyika, was still south of the Equator and he did not penetrate the rainforest of the River Congo any further downstream than Ntangwe near Misisi.[7]

Livingstone was awarded the gold medal of the Royal Geographical Society of London and was made a fellow of the society, with which he had a strong association for the rest of his life.[2]

Livingstone and slavery

"And if my disclosures regarding the terrible Ujijian slavery should lead to the suppression of the East Coast slave trade, I shall regard that as a greater matter by far than the discovery of all the Nile sources together." - Livingstone in a letter to the editor of the New York Herald.[8]

Livingstone's letters, books, and journals[9] did stir up public support for the abolition of slavery;[10] however, he became humiliatingly dependent for assistance on the very slave-traders whom he wanted to put out of business. Because he was a poor leader of his peers, he ended up on his last expedition as an individualist explorer with servants and porters but no expert support around him. At the same time he did not use the brutal methods of maverick explorers such as Stanley to keep his retinue of porters in line and his supplies secure. For these reasons from 1867 onwards he accepted help and hospitality from Mohamad Bogharib and Mohamad bin Saleh (also known as Mpamari), traders who kept and traded in slaves, as he recounts in his journals. They in turn benefited from Livingstone's influence with local people, which facilitated Mpamari's release from bondage to Mwata Kazembe.[9]

Livingstone was also furious to discover some of the replacement porters sent at his request from Ujiji were slaves.[9]

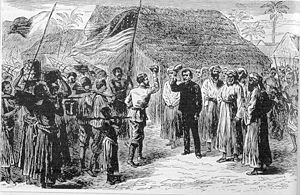

Illness, pain and, death

Livingstone completely lost contact with the outside world for six years and was ill for most of the last four years of his life. Only one of his 44 letter dispatches made it to Zanzibar. Henry Morton Stanley, who had been sent to find him by the New York Herald newspaper in 1869, found Livingstone in the town of Ujiji on the shores of Lake Tanganyika on 10 November 1871,[11] greeting him with the now famous words "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?" These famous words may be a fabrication, as Stanley has torn out the pages of this encounter in his diary.[12] Even Livingstone's account of this encounter does not mention these words. However, the phrase appears in a New York Herald editorial dated 10 August 1872 and the Encyclopaedia Britannica and the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography both quote it without questioning its validity.

A possibly apocryphal story is included in Presidential Elections by Paul F. Boller, Jr. (1985). The story goes that Stanley told Livingstone what had occurred in Europe and America during his expedition; among other things he said that the 1872 U.S. presidential election campaign had begun and the Democratic Party had nominated Horace Greeley. Livingstone stopped Stanley there; he said, "You have told me curious things and wonderful, but there is a limit--when you tell me the Democrats have nominated Greeley for President I am hanged if I will believe it."

Some in Burundi claim the famous meeting took place 12 km south of Bujumbura at the spot marked by the Livingstone-Stanley Monument, Mugere, but that marks a visit they made 15 days after their first meeting - see linked article for references - on their joint exploration of the north end of Lake Tanganyika, which ended when Stanley left in March the next year.

Despite Stanley's urgings, Livingstone was determined not to leave Africa until his mission was complete. His illness made him confused and he had judgment difficulties at the end of his life. He explored the Lualaba and failing to find connections to the Nile, returned to Lake Bangweulu and its swamps to explore possible rivers flowing out northwards.[9]

David Livingstone died in that area in Chief Chitambo's village at Ilala southeast of Lake Bangweulu in Zambia, on 1 May 1873 from malaria and internal bleeding caused by dysentery. He took his final breaths while kneeling in prayer at his bedside. (His journal indicates that the date of his death would have been 1 May, but his attendants noted the date as 4 May, which they carved on a tree and later reported; this is the date on his grave.) Livingstone's heart was buried under a Mvula tree near the spot where he died, now the site of the Livingstone Memorial. His body together with his journal was carried over a thousand miles by his loyal attendants Chuma and Susi, and was returned to Britain for burial in Westminster Abbey.[2]

Livingstone's legacy

By the late 1860s Livingstone's reputation in Europe had suffered owing to the failure of the missions he set up, and of the Zambezi Expedition; and his ideas about the source of the Nile were not supported. His expeditions were hardly models of order and organisation.[5]

His reputation was rehabilitated by Stanley and his newspaper,[5] and by the loyalty of Livingstone's servants whose long journey with his body inspired wonder. The publication of his last journal revealed stubborn determination in the face of suffering.[2]

He had made geographical discoveries for European knowledge. He inspired abolitionists of the slave trade, explorers and missionaries. He opened up Central Africa to missionaries who initiated the education and health care for Africans, and trade by the African Lakes Company. He was held in some esteem by many African chiefs and local people and his name facilitated relations between them and the British.[2]

Partly as a result, within fifty years of his death, colonial rule was established in Africa and white settlement was encouraged to extend further into the interior.

On the other hand, within a further fifty years after that, two other aspects of his legacy paradoxically helped end the colonial era in Africa without excessive bloodshed. Livingstone was part of an evangelical and nonconformist movement in Britain which during the 19th century changed the national mindset from the notion of a divine right to rule 'lesser races', to ethical ideas in foreign policy which, with other factors, contributed to the end of the British Empire.[13] Secondly, Africans educated in mission schools founded by people inspired by Livingstone were at the forefront of national independence movements in central, eastern and southern Africa.[14]

Family life

While Livingstone had a great impact on British Imperialism, he did so at a tremendous cost to his family. In his absences, his children grew up fatherless, and his wife Mary (daughter of Mary and Robert Moffat) eventually died of malaria trying to follow him in Africa. He had six children: Robert reportedly died in the American Civil War[15]; Agnes, Thomas, Elizabeth (who died two months after her birth), William (nicknamed Zouga for the river along which he was born) and Anna Mary. His one regret in later life was that he did not spend enough time with his children.[16]

Archives

The archives of David Livingstone are maintained by the Archives of the University of Glasgow (GUAS).

Places named in his honor and other memorials

In Africa

- The Livingstone Memorial in Ilala, Zambia marks where he died.

- The city of Livingstone, Zambia which includes a memorial in front of the Livingstone Museum and a new statue erected in 2005.[17]

- The Rhodes-Livingstone Institute in Livingstone and Lusaka, Zambia, 1940s to 1970s, was a pioneering research institution in urban anthropology.

- David Livingstone Teachers Training College, Livingstone, Zambia.

- The David Livingstone Memorial statue at Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, erected in 1954 on the western bank of the falls.

- A new statue of David Livingstone was erected in November 2005 on the Zambian side of Victoria Falls.[17]

- A plaque was unveiled in November 2005 at Livingstone Island on the lip of Victoria Falls marking where Livingstone stood to get his first view of the falls.[17]

- The town of Livingstonia, Malawi.

- The city of Blantyre, Malawi is named for his birthplace in Lanarkshire, Scotland, and includes a memorial.

- The David Livingstone Scholarships for students at the University of Malawi, funded through Strathclyde University, Scotland.

- The Kipengere Range in south-west Tanzania at the north-eastern end of Lake Malawi is also called the Livingstone Mountains.

- Livingstone Falls on the River Congo, named by Stanley.

- The Livingstone Inland Mission, a Baptist mission to the Congo Free State 1877-1884, located in what is now Kinshasa.

- A memorial in Ujiji commemorates his meeting with Stanley.

- The Livingstone-Stanley Monument, Mugere, Burundi marks a spot that Livingstone and Stanley visited on their exploration of Lake Tanganyika, mistaken by some as the first meeting place of the two explorers.

- There is a memorial to Livingstone at the ruins of the Kolobeng Mission, 40 km west of Gaborone, Botswana.

- The church tower of the Catholic Holy Ghost Mission in Bagamoyo, Tanzania, is called Livingstone Tower because his body was laid down there for one night before it was shipped to London.

- Livingstone House in Stone Town, Zanzibar, provided by the Sultan for Livingstone's use, January to March 1866, to prepare his last expedition; the house was purchased by the Zanzibar government in 1947.

- Plaque commemorating his departure from Mikindani on his final expedition on the wall of the house that has been built over the house he reputedly stayed in.

- David Livingstone Primary School in Harare, Zimbabwe.

In Scotland

- A statue stands near the base of the Scott Monument in the Princes Street Gardens, Edinburgh, Scotland.

- The David Livingstone Centre in Blantyre, Scotland, is a museum in his honour.

- David Livingstone Memorial Primary School in his birthplace, Blantyre, Lanarkshire, Scotland.

- David Livingstone Memorial Church of the Church of Scotland, in Blantyre, Lanarkshire, Scotland.

- A bust of David Livingstone is among those of famous Scotsmen in the William Wallace Memorial near Stirling, Scotland.

- Strathclyde University, Glasgow (successor to Anderson's University), commemorates him in the David Livingstone Institute for International Development Studies, the David Livingstone Centre for Sustainability, and Livingstone Tower.

- The David Livingstone (Anderson College) Memorial Prize in Physiology commemorates him at the University of Glasgow.

In England

- His grave is marked in Westminster Abbey, London.

- The Royal Geographic Society has a statue of Livingstone in the hall of their London headquarters.

- The London Missionary Society named their headquarters Livingstone House, in Carteret St, London SW1.

- Dr Livingstone's, a series of nightclubs in the North of England.

- David Livingstone Primary School, Thornton Heath, London.

- Livingstone Primary School, New Barnet, London.

- Livingstone Primary School, Mossley, Tameside.

In Canada

- The Livingstone Range of mountains in southern Alberta.

- David Livingstone Elementary School, Vancouver

- David Livingstone Community School, Winnipeg

- Bronze bust in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

In the USA

- Livingstone College, Salisbury, North Carolina.

- Livingstone Adventist Academy, Salem, Oregon.

Banknotes

From 1971-1998 Livingstone's image was portrayed on £10 notes issued by the Clydesdale Bank. He was originally shown surrounded by palm tree leaves with an illustration of African tribesmen on the back.[18] A later issue showed Livingstone against a background graphic of a map of Livinstone's Zambezi expedition, showing the River Zambezi, Victoria Falls, Lake Nyasa and Blantyre, Malawi; on the reverse, the African figures were replaced with an image of Livingstone's birthplace in Blantyre, Scotland.[19]

In popular culture

- In the film The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Arthur Dent dresses up as Dr Livingstone at a fancy dress party.

- In 1939, a popular film called Stanley and Livingstone was released, with Cedric Hardwicke as Livingstone and Spencer Tracy as Stanley, portraying the works Livingstone did in Africa.

- "Dr. Livingstone, I Presume" is a song written by Artie Shaw and recorded by Artie Shaw & His Orchestra in the early 1940s.

- A different song entitled "Dr. Livingstone, I Presume" appears on the 1968 Moody Blues album, In Search of the Lost Chord.

- Mountains of the Moon is a 1990 film in which Livingstone is portrayed by Bernard Hill.

- "What about Livingstone" is a song by Swedish pop group ABBA on the album "Waterloo".

- Livingstone appears on the album cover for The Beatles' Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. The cover was a collage made by artist Peter Blake. Livingstone appears in the third row.

- In 1997, a made for television movie called "Forbidden Territory: Stanley's Search for Livingstone" was produced by National Geographic. Stanley was portrayed by Aidan Quinn and Livingstone was portrayed by Nigel Hawthorne.

- "Doctor Livingstone" is a song by Crowded House which is on their Afterglow album (1999).

- The fish seen in the background of Captain Picard's ready room in the popular television series Star Trek The Next Generation is named Livingston after the famous explorer.

- The fifth season episode of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine is entitled: Doctor Bashir, I Presume? where we learn that Dr. Julian Bashir received genetic enhancements as a young boy.

- In the Get Smart reunion movie, "Get Smart Again", Max says "Dr. Hottentot I Presume".

- A video game was released for the Nintendo Entertainment System entitled "Stanley and the Search for Dr. Livingston."

- A video game was released for the ZX Spectrum and other 8-bit computers called "Livingstone Supongo"[20] ("Livingstone, I presume" in its UK release).

- In the video game Far Cry 2 a trophy/achievement called "Dr Livingstone, I presume" is awarded for entering every square kilometer of the map of a fictional region of Africa.

See also

- David Livingstone Centre (museum in Blantyre, Lanarkshire, Scotland)

- Thomas Baines

- John Kirk

- Livingstone Inland Mission

- The Historical Background to Church Activities in Zambia

References

- ↑ John M. Mackenzie, "David Livingstone: The Construction of the Myth," in Sermons and Battle Hymns: Protestant Popular Culture in Modern Scotland, ed. Graham Walker and Tom Gallagher (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1990).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Blaikie, William Garden (1880): The Personal Life Of David Livingstone. Project Gutenberg Ebook #13262, release date: 23 August 2004].

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 A.D. Roberts, "Livingstone, David (1813-1873)," Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

- ↑ Tim Jeal, Livingstone (London: Heinemann, 1973), 56-57, 74.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Tim Holmes: "The History" in: Spectrum Guide to Zambia. Camerapix International Publishers, Nairobi. 1996

- ↑ 'Into Africa: The Epic Adventures of Stanley and Livingstone' (2003), Martin Dugard

- ↑ "Map of Livingstone's travels". National Museums of Scotland. The map is online at www.scran.ac.uk but a subscription to the site is required to view it.

- ↑ Stanley Henry M., How I Found Livingstone; travels, adventures, and discoveries in Central Africa, including an account of four months' residence with Dr. Livingstone. 1871.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 David Livingstone & Horace Waller (Ed): The Last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa from 1865 to his Death. Two Volumes. John Murray, London, 1874.

- ↑ BBC.co.uk/History Historic Figures: "David Livingstone" accessed on 1 February 2007

- ↑ Northern Rhodesia Journal online: "David Livingstone chronology." Vol V, No. 3 (1963). Note that Livingstone records the date as 24 October since he was by then 16 days out in his date reckoning. Accessed 23 March 2007.

- ↑ Jeal, Tim (2007). Stanley: The Impossible Life of Africa's Greatest Explorer. Faber and Faber. ISBN 0571221025.

- ↑ Corelli Barnett: The Audit of War: The Illusion and Reality of Britain as a Great Nation (Macmillan, 1986)

- ↑ Richard Seymour Hall: "Kaunda, founder of Zambia". Longman, 1967.

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/stable/view/716469?seq=2

- ↑ Niall Ferguson: "Empire: The rise and demise of the British world order and the lessons for global power". Basic Books, 2003.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 The Times of Zambia online: "David Livingstone remembered", 15 November 2005 - 23 November 2005. Website accessed 26 April 2007.

- ↑ "Clydesdale 10 Pounds, 1982". Ron Wise's Banknoteworld. Retrieved on 2008-10-15.

- ↑ "Clydesdale 10 Pounds, 1990". Ron Wise's Banknoteworld. Retrieved on 2008-10-15.

- ↑ "Livingstone Supongo". World of Spectrum. Retrieved on 2008-10-30.

Other sources

- Tim Butcher: Blood River - A Journey To Africa's Broken Heart, 2007. ISBN 0-701-17981-3

- Holmes, Timothy. Journey to Livingstone: Exploration of an Imperial Myth. Edinburgh: Canongate Press, 1993.

- Jeal, Tim (1973). Livingstone. London: Heinemann. pp. 427p. ISBN 0-434-37208-0.

- Martelli, George. Livingstone's River: A History of the Zambezi Expedition, 1858-1864. London: Chatto & Windus, 1970.

- Ross, Andrew C. David Livingstone: Mission and Empire. London and New York: Hambledon and London, 2002.

- Nourbese Philip, Marlene. Looking for Livingstone: An Odyssey of Silence, Toronto: The Mercury Press, 1991.

- Livingstone, David. Dernier Journal. Arléa, 1999 – ISBN 2-86959-449-6 (French)

- Eynikel, Hilde. Mrs. Livingstone: een biografie. Davidsfonds, 2005, 487 pages - – ISBN 90-5826-347-9 (Dutch)

- Livingstone, David (1905) [1857] (book). Journeys in South Africa (or Travels and Researches in South Africa. London: The Amalgamated Press Ltd..

External links

- Works by or about David Livingstone at Internet Archive (scanned books original editions color illustrated)

- Works by David Livingstone at Project Gutenberg (plain text and HTML)

- A Brief Biography of David Livingstone

- The Life of David Livingstone

- Livingstone Online - Explore the medical writings of David Livingstone

- David Livingstone biographies